Recently I found myself sitting in a cafe near Galway's Eyre Square, drinking a latte that tasted vaguely of paper, and scrolling through my phone. For the first twenty minutes of this experience, the only thing of note was that the latte was not served in a paper cup and thus had no right to be paper-flavored. Yet my attention was directed away from this by an ad on my Instagram; one for this very platform. Specifically a contest on this platform concerning unpopular opinions. This intrigued me for two reasons. Firstly, the contest promised a cash prize, and I need money to continue buying disappointing coffee in Irish cafes. Secondly, I have been harboring an unpopular opinion of my own for some time. An opinion that goes against a sizable portion of agreed-upon public imagination of ancient Rome, so I would say a pretty unpopular one.

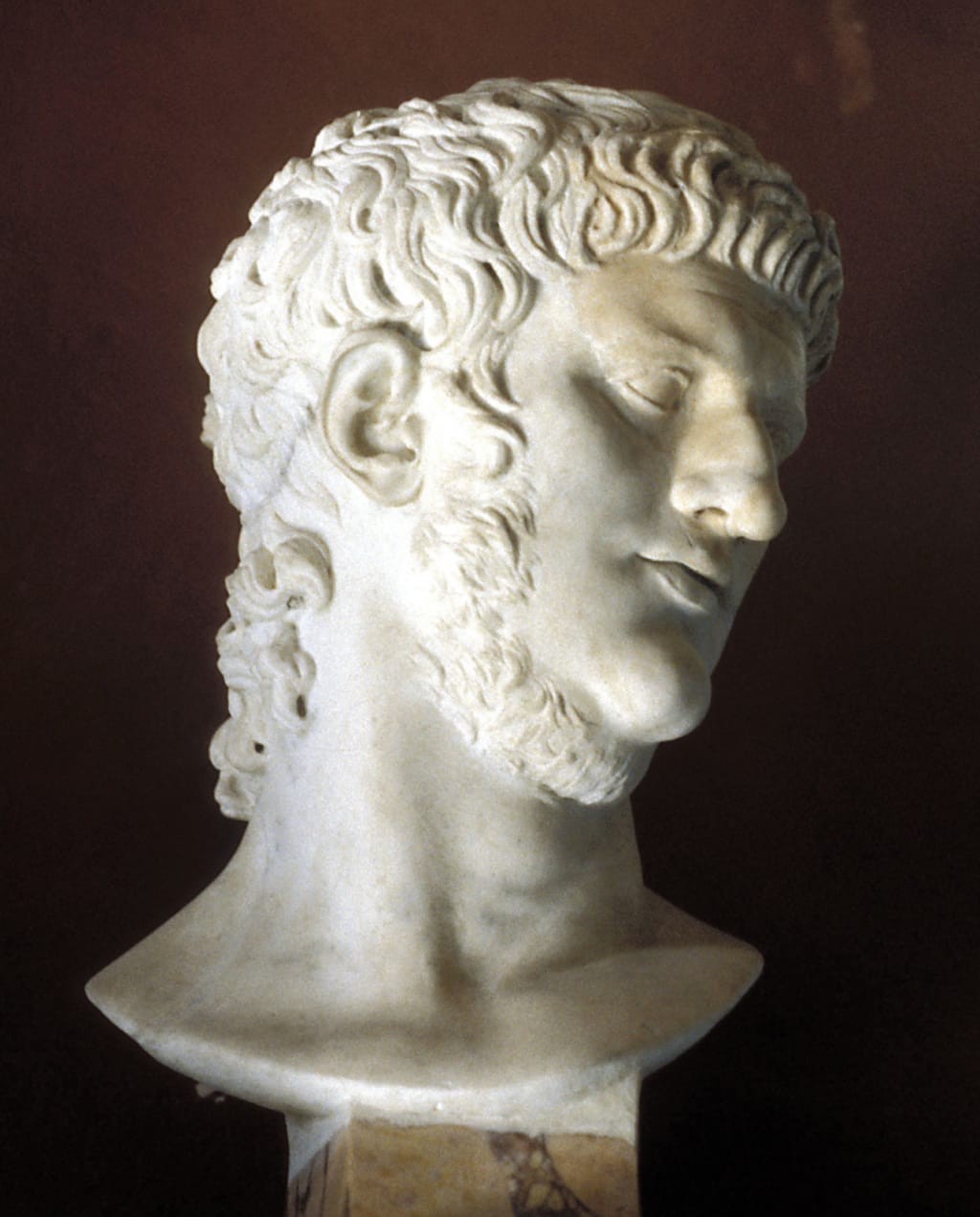

I don't think Emperor Nero was really that bad.

I feel like I should preface this by saying that I am by no means a scholar of Roman history or claim to be an expert in any field. I'm just a pseudo-intellectual with avoidant personality disorder, which means I have more time to think about nonsense like this, as I have few close personal relationships. I'm also not at all saying that Nero was all around a good person, or that there has been some sort of conspiracy to tarnish his legacy (although I may end up saying the latter). I'm not excusing any of the crimes he's proven to have committed either, though I'll do my best to try to address them with as much sensitivity as possible.

All I'm putting out there is that our understanding of Nero is flawed. Much of it is based on nothing more than historical hearsay, and I think we need to change that.

Most of our unfavorable opinion of Nero comes from other Romans, who have passed down the stories of his excess, debauchery, and alleged arson. In The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Roman historian Suetonius writes that Nero "had planned to call Rome Neropolim". Another Roman historian, Cassius Dio, accuses Nero of plotting to murder the entire Senate, burn down the city of Rome, and try to sneak away from Alexandria. Both of them claim that the people of Rome celebrated after his death. But some have called this characterization into question. For instance, the celebrating of Nero's death was likely limited to a specific demographic in Rome. While he initially proved to be popular with the Senate, he soon grew to be a thorn in their side. In the early years of his reign, Nero pursued reforms and tax increases that made him popular among the common people, but fed resentment in the Roman establishment. His artistic pursuits and eccentricities made the army resent him, as they felt he neglected the military in order to pursue music and poetry, according to Richard Holland, author of Nero: The Man Behind The Myth. While the wealthiest of Romans welcomed the news of Nero's demise, the common people were mournful. A legend even emerged in the Empire's eastern province, of a secretly-alive Nero plotting to return. Known as the "Nero Revividus Legend", this, along with the commoner's mourning, were documented by Tacticus in Histories.

Stories of Nero's popularity among the common people, and especially "Nero Revividus" (along with a slew of impersonators claiming to be the fulfillment of this legend) point to an image of far more than simply the violent, insane man-child Nero's has ultimately become. Despite the fact that there have been grumblings in the academic community for years about Nero's legacy, and the validity of the sources behind it, the general public consensus still seems to be Nero=bad. This is, however, due to more than just Nero's alienation from the Roman establishment and their subsequent efforts to tarnish him both pre-and-post-mortem.

A lot of it is messier.

In 64 AD, seventy-percent of the city of Rome was destroyed in a fire over the course of about a week. It was nicknamed "The Great Fire of Rome", when it was in actuality it was pretty terrible. It is popular legend that "Nero fiddled during the great fire of Rome." There was even a recent comparison between Nero and Donald Trump, based on this exact legend. Leaving aside the fact that the instrument in question wouldn't be invented for at least 1000 more years, this claim is dubious. In reality, Nero, who wasn't actually in the city when the fire broke out, quickly returned and took swift action on behalf of those affected, personally organizing the relief efforts. Suetonius even gave Nero credit for his aid to the Roman people during the fire, writing that Nero "let slip no opportunity for generosity and mercy."

The negative myth that has sprung up surrounding Nero's conduct concerning the fire likely comes from another, more reasonable rumor. Many contest that Nero himself had the fire started, so that he could rebuild certain parts of the city to be more aesthetically pleasing to him. This, to me, sounds to me like a bit of a stretch. Obviously he was going to rebuild the city, seventy-percent of it was destroyed. You can't exactly run an empire from thirty-percent of a city. This rumor, as well as the anachronistic fiddle myth, feed into the narrative of the petulant Nero, and thus is easy to accept. But subjected to historical scrutiny, they tend to unravel.

The great fire leads us into another unsavory facet of Nero's reign. Tacticus recorded in his Annals that Nero almost immediately set about scapegoating the "Chrestians" (his spelling), and "inflicted a torture most exquisite" on them in revenge. It's important to note that, although he's considered reliable, Tacticus is the only source that points to Nero blaming the Christians for the fire. In fact, Suetonius only mentions Nero publicly torturing Christian men before the fire. Not that that's better, obviously it is still incredibly terrible. There's also no visible evidence that Nero's regime ever had any law against practicing Christianity. However it is likely that Nero features in The Book of Revelation, as the "Beast". As Nero was recorded by both Tacticus and Suetonius to have inflicted torture upon the Christians, those who follow the "preterist" interpretation of Revelation generally agree that "the beast" or the antichrist, were meant to be interpreted as Nero. The number 666 is equivalent to Nero Caesar in Hebrew and Aramaic. It is in fact the Nero coding of The Book of Revelation that got me interested in Nero's life in the first place, so I guess that's cool.

Nero is not the only Roman emperor to engage in persecution of the Christians, though he does hold the, uh, distinction of being the first. This element of Nero's story, I can't refute, nor can I offer any. But it's important, at least in my mind, to properly distinguish the truth from the myths.

One story about Nero that is backed up by records is his murder of his own mother. Julia Aggrippina, or Aggrippina the younger, worked extremely hard to get her son to where he was, including marrying (and possibly) murdering her uncle Cladius. She essentially tried to be the regent of Rome during Nero's early years, but her son slowly pushed her aside, and finally had her murdered in 68 A.D. It is horrifying, and a disturbing reality of the struggle for power in Rome. Aggrippina isn't even Nero's only murder of a loved one. But to me, this speaks more to the immorality bred from the mad struggle for the throne. Stories of assassinations and the plotting thereof are plentiful, and speak to the corruptive nature of the institution of the Empire. I'm not excusing these actions by any means, but Nero, as well as his mother, were products of their environment.

So despite his proven abhorrent behavior, much of the commonly accepted knowledge of Nero ultimately proves to be untrustworthy, calling into question his labeling as "evil". Ultimately, it seems that though Nero participated and contributed to the bloodshed that defined the struggle for power in ancient Rome, that he in fact used his political power to attempt to improve the lives of his people. But those who benefited from Roman social inequity, and militaristic expansionism, strongly disagreed with his policies, celebrated his death, and passed down stories of "Rome's worst emperor." This label, outside of a few scholars re-examining the validity of these sources, has stuck.

Why do I care so much about some matricidal poet who just so happened to be the emperor of Rome? Maybe the idea of the wealthy classes intentionally spreading negative propaganda about someone who genuinely does try to make life better for all peoples rubs me the wrong way, and I feel like we need to rework our understanding of Nero in order to try and dismantle these kinds of narratives. make this tactic ineffective. Or maybe not. Maybe I just need someone to talk to.

About the Creator

jenny

all hail the universal friend

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.