Pride: The 1984 Miners' Strike

‘To what extent did the 1984 Miners’ Strike have a significant impact on the increase of awareness and acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community in the United Kingdom?’ I wrote this piece for my EPQ during college and I was very proud of it. I got a C grade but I wanted to share my findings.

Since the initial criminalisation of homosexual relations between two males during the Roman Empire, the LGBTQ+ community has faced much discrimination and oppression, despite the many famous and powerful figures throughout history who have been openly or privately involved in homosexuality. Such figures have seen varying levels of acceptance or discrimination; for example, King James had three serious male lovers whom he placed as his favourites in politics. It was well known that he favoured these men and some were brought before the King with the intent to change the "favourite" dynamic within the King’s Court. In comparison, Alan Turing was condemned for his homosexuality and was made to take hormonal altering drugs. When he was convicted of "gross indecency," he was given the option of jail or chemical castration. Ultimately, he chose the latter but it caused him to suffer much horrendous physical and mental distress; including impotency, breast development, and depression. He committed suicide two years later, at the age of 41 (Tatchell 2014). Although typically one may not think that the 1980s were a particularly progressive or welcoming time for the LGBTQ+ community, there were many advances made that increased awareness and acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community and their struggles. One factor that contributed to the change in social and political attitudes to homosexuality was the Miners’ Strike of 1984.The relationship built between London LGSM and the mining communities of Neath, DuLais, and Swansea and beyond led to both major political advancement in the rights of the LGBTQ+ community but also a change in attitude from society as a whole. Whether or not the Miners’ Strike and LGSM had a majorly significant impact on changing social and political attitudes is somewhat contentious as the 1980s were a major time of change already for the LGBTQ+ community prior to the Strike, in part due to the AIDS/HIV hysteria which created much stigma surrounding gay relationships. This essay will assess the significance of the 1984 Miners’ Strike in comparison to other factors that occurred prior to and in the same time period as the strike to evaluate the strike’s overall impact.

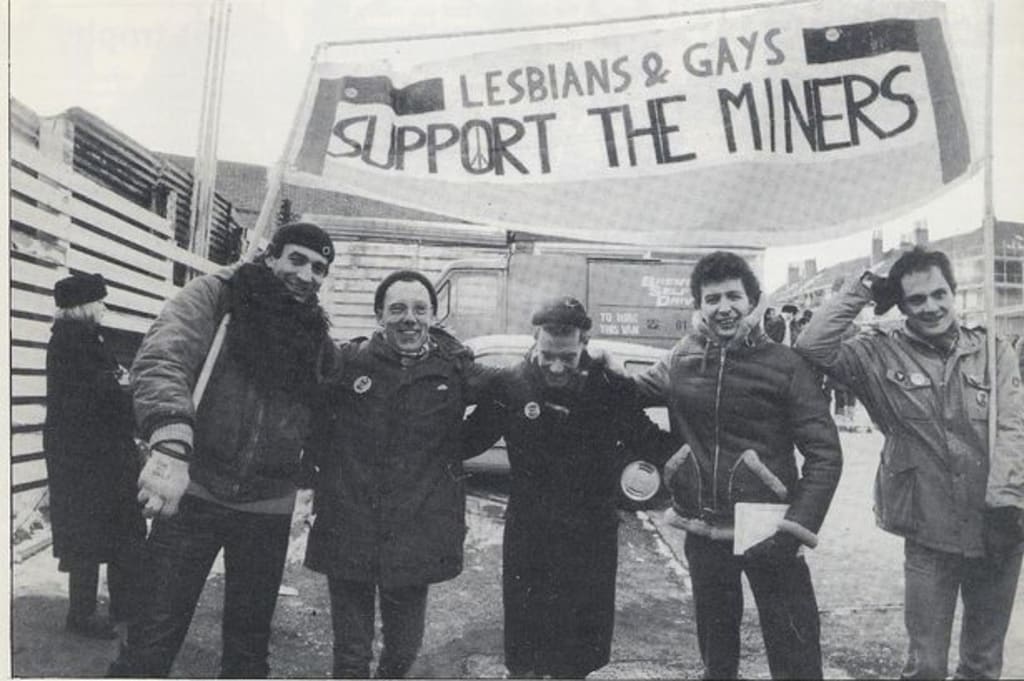

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) started as a support group based in London’s Gay’s The Word bookshop. The group formed four months into the 1984 Miners’ strike co-founded by Mark Ashton and Mike Jackson. They raised £11,000, the equivalent to £30,585 in 2016, to support the strike (Fisher 2014), making them one of the most influential support groups during the strike. As a result of the support shown by LGSM to mining communities, a block vote from the National Union of Mineworkers was vital to passing gay rights into the Labour Party agenda. At the Bournemouth Conference in 1985, Labour Campaign for Lesbian and Gay Rights (LCLGR) won a card vote against the National Executive Committee with the support of trade unions (Labour 2018). The work of LGSM was greatly underappreciated until the release of the film Pride (2014) written by Stephen Beresford. The film “has helped to preserve a little bit of history that could very easily have been lost forever” (Appendix 1) and has given new life to the movement of creating solidarity between groups that have been are or being attacked by the government. Their work mostly consisted of working with a small isolated community in the Swansea, Neath, and Dulais Valley that relied on mining to survive. They would travel from London to South Wales to take boxes of food, warm clothes in the winter, and the money they had collected from fundraisers and bucket collections. The event that raised the most money was the Pits and Perverts charity ball held at the Electric Ballroom where Bronski Beat (an openly gay band) headed the bill and where £5,650 was raised for the miners (Turner 2014). Alongside the influence that LGSM had on the miners, their work also influenced the awareness and acceptance of the queer community. The miners’ strike came at a time of significant change in all of society for both queer and straight communities. This could suggest that in regards to greater society the Miners’ Strike was one minor factor; however, there is much evidence to suggest it was the strike that propelled the activism already in place into major action increasing its significance in general.

Prior to the 1984 Miners’ Strike, there were changes in both the law and some social attitudes towards homosexuality. These began in particular in the 1960s as it was a time of sexual liberation. Female sexuality and homosexuality became more accepted leading to the formation of an openly queer community that had not been seen before, this also lead to the beginning of the gay rights movement with many early gay rights activists. What is often considered the beginning of gay liberation was The Sexual Offences Act 1967 which decriminalised sexual acts between men both aged over 21 "in private." It was the first gay law reform since 1533 when anal sex was made a crime during the reign of Henry VIII; all other sexual acts between men were outlawed in the Victorian era in 1885 (Tatchell 2017), although it has been argued by activist Peter Tatchell that this was not liberation for the gay community as it was limited and there was still much more reform that needed to happen before the LGBTQ+ community could be considered liberated (Tatchell 2017). The decriminalisation was a major change in the acceptance of the gay community as it began to give gay men some of the same rights as heterosexuals, and more specifically, it began to show that homosexuality was not something that should be punishable by imprisonment or incarceration. However, homosexuality was not fully decriminalised until 2013 when gay sex was legalised in Scotland. This suggests that people were not truly accepting of the legitimacy of homosexual relationships and homosexual rights to liberation until the final decriminalisation. This argument can be further seen as even after The Sexual Offences Act 1967 old anti-gay homophobic laws proceeded to be enforced more viciously with 15,000 gay men being convicted in the following years and between 1885 and 2013 nearly 100,000 men were arrested for same-sex acts (Tatchell 2017). Peter Tatchell, writer for The Guardian, former-politician and LGBTQ+ activist, experienced homophobia during his campaign as Labour Party Parliamentary candidate for the Bermondsey by-election 1983. There was much use of homophobic fear mongering in particular by the Liberal Party candidate Simon Hughes. A leaflet was produced entitled “The Straight Choice” (Grice 2006). This shows that prior to the Miners’ Strike it was seen as unacceptable to elect an openly gay candidate. This view caused much of the campaign of the Liberal Party and more right-wing Labour Party supporters to be directed by anti-Tatchell and pro-homophobia slogans. Tatchell claims that, "Some of their male canvassers went around the constituency wearing lapel stickers emblazoned with the words 'I've been kissed by Peter Tatchell,' in a blatant bid to win the homophobic vote” and that “on the doorsteps, they spread false rumours that I was chair of the local gay society; no such society existed." Furthermore, Tatchell was personally attacked by his home phone number and address being put out as part of the homophobic campaign on the "Which Queen Will You Vote For?" leaflet (Grice 2006). The experience of Peter Tatchell shows the attitude that homophobia, discrimination, and hate were more acceptable than homosexuality being part of the public view. The fact that Liberal Party candidate Simon Hughes was also gay (Grice 2006) suggests that the attitude towards gay people and gay people in prominent positions was that of discretion and privacy. Arguably, homosexuality was seen as something to be kept private and not to be spoken about in a public forum. This can be inferred as Simon Hughes won the election by hiding behind a homophobic campaign and not coming out about his sexuality. Peter Tatchell’s experiences as a gay political nominee are somewhat representative of the opinions of society at large as it holds the ideas of fear mongering and the desire for homosexuality to be kept quiet and not interfere with straight society. The "pretty police" were used to lure men into committing homosexual offences (Tatchell 2017). This shows that socially homosexuality was not being accepted as people still wanted to enforce the old homophobic laws.

The Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) was formed in 1964 and campaigned for homosexual rights and equalities. They were a driving force in the passing of The Sexual Offences Act 1967 (CHE 2015). Their support and formation marks a real start in the push for gay rights across the country and they had a significant impact during the 1960s which was the basis for activism during the 1980s. Their impact was felt by activist groups such as LGSM in the 1980s. Mike Jackson claims that the activism of the 80s was “only part of an ongoing campaign, really been carrying on since the 1960s.” Gay rights activist Allan Horsfall worked for the National Coal Board whilst living in a mining community in south-Lancashire (Tate 2014). He became secretary for the North-Western Homosexual Law Reform Committee (NWHLRC) who campaigned for the decriminalisation of homosexual sex in the late 1950s and into the 1960s (CHE 2015). This shows that there was active support in a few mining communities for the LGBTQ+ rights and equalities; however, these were more personal and did not extend to large-scale political action. It was thought by politicians that gay law reforms would not “go down in my constituency with the miners." However, Horsfall took the attitude that he was “publishing from the middle of a mining village, and I find it all right. I don't know what Skinner's on about." (Guardian 2004). This suggests that in rural working class communities, there was localised acceptance of homosexuality based on personal experiences with neighbours, but this acceptance was often not wide-spread and did not extend to the LGBTQ+ as a whole.

However, the Miners’ Strike was not the only event that had a significant impact on changing views. In the same year (1984) Labour MP Chris Smith became the first politician to voluntarily come out as gay (Bentley 2010). This shows progress being made during the 80s that was in many ways unprecedented. The significance of this is seen as previously to Smith’s election. Sexuality was used to attack political candidates and they were forced "out of the closet" rather than voluntarily. The difference in attitude between Tatchell’s 1983 by-election and Smith’s 1984 election suggests that there were significant changes in attitudes happening very quickly. One may argue that it was the solidarity created by the Miners’ Strike for minority groups that reduced the prejudices against a homosexual candidate. LGSM member Ray Goodspeed said that “Chris Smith coming out was HUGE for the Labour movement activists and boosted out campaign inside the Labour and Trade Union movement” (Appendix 2).

The gay scene in the 1980s was to a large extent characterised by the AIDS/HIV hysteria. AIDS/HIV was the focus of gay culture in the media with many newspapers using the fear surrounding the disease to challenge the work being done by gay rights activists and to push back progress on queer acceptance. Awareness was raised surrounding the gay community due to the AIDS/HIV hysteria of the 80s which brought attention to sex in the gay community. It has been said that “in some senses that helped people become aware what gay oppression was about, from a humanitarian point of view alone were prompted to become aware about life for gay men when they saw those shocking headlines and reports” (Appendix 1). However, this was, to a large extent, very negative attention that was used to discriminate against gay men and create fear of the LGBTQ+ community. Initially, AIDS/HIV was known as GRID, meaning Gay Related Immune Deficiency, colloquially known as the "gay plague" or "the gay cancer" (Clews 2017). This shows that people were happy to accept AIDS as punishment and consequence of being gay. This did increase queer visibility; however, it was used to excuse homophobia and discrimination. Mike Jackson, co-founder of LGSM, says of the impact of AIDS/HIV, “On the darker side, there was the emergence of AIDS/HIV and all though there was some awful stuff in the media about gay men around that notably Rupert Murdoch's son and his gay plague headline. Although it was very dark it had a positive influence on some people. Really before '85 in Britain, AIDS was only just starting to develop. It was a bit later than it was in the States, and when Mark [Ashton] died on 11th of February 1987, that mining community came to his funeral and spent a lot of time and effort campaigning for that and AIDS awareness counteracting negative press coverage and indeed collecting money for AIDS charities.” Here it is obvious that the Miners’ Strike was influential on changing attitudes of wider society as they did the unexpected and returned the help of LGSM and LGBTQ+ people in their fight against not just AIDS/HIV itself but also the representation and attitudes towards it. Before the AIDS crisis, “A major problem before had been invisibility which allowed all sorts of ideas of homosexuals as some dangerous, ridiculous, sick, exotic, weird people to develop.” This shows how there were some positive outcomes of the increase in attention on the gay community. Due to the AIDS/HIV hysteria, gay men were asked not to donate blood (Gunson 1986) as research had shown that the virus could be transferred through blood. The removal of this opportunity acted as villainization of the queer community as they were seen as the sole cause of AIDS/HIV. AIDS/HIV was used by tabloids to out celebrities or to suggest they had been committing crimes. For example, television presenter Russell Harty was reported as dying of AIDS due to paying for underage rent boys, however, he did, in fact, die from Hepatitis B which The Sun reported as ‘a disease transmitted in the same way as AIDS’ (Morrison 2009). The use of a reference to ‘AIDS’ is representative of how AIDS/HIV was seen as such an awful disease and how homosexuality was seen as a worthy reason for death to some extent. This shows how increased visibility for queer people was often not positive and was used to ruin the careers and lives of prominent queer members of society. The work done by gay activists that was not AIDS/HIV related during the crisis was not considered, by the gay community, as the correct thing to be doing. This was felt by the group LGSM whose work for the miners was seen as inferior. For many people, they “dropped everything because it was so important” when it came to working for AIDS/HIV. LGSM “got a little bit of flack actually as a result of that because one criticism we would get from members of the gay community, particularly gay men, well almost exclusively gay men, [was] why are you collecting for the miners, you should be out there collecting for the AIDS charities. What I learnt to do with that criticism was to turn around to these people and say, ‘before I answer that question can you tell me what you do for the gay community in terms of AIDS/HIV,’ and almost inevitably they didn’t do anything for anybody. I rest my case. The reality was the people in LGSM weren’t just supporting the miners. We came from a political position of being campaigners, activists within the community. So naturally we worked towards AIDS awareness and collecting” (Appendix 1).

The representation of homosexuality on television was sporadic in its positive presentation of gay relationships. Although there was an increase in the number of homosexual characters and relationships in the media and on television programmes, the characters represented were often stereotyped over exaggerated characters such as Mr Humphries from Are You Being Served? The character of Mr Humphries was very camp and effeminate in his mannerisms and other characters described him using lightly homophobic language such as references to being a “queen.” In terms of adult and sexual relationships between homosexuals, there was a "no sex please, I’m homosexual" culture across the globe within the media industry (Clews 2017). This shows that although production companies were making some efforts to include gay relationships in television, it was still seen as taboo and those relationships were not able to experience the same representation. The first onscreen gay (forehead) kiss on EastEnders in 1986 led to The Sun nicknaming it "East Benders" (Clews 2017). Former actor and Labour MEP Michael Cashman played Colin, one half of the first gay kiss on EastEnders, recalls how “there were questions in Parliament about whether it was appropriate to have a gay man in a family show when AIDS was sweeping the country” (Brooks 2003). This shows how drastic and controversial gay relationships were when they were presented to the general public, in particular children and families. Despite this, there were gay-themed films being produced in Britain, such as My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), which featured an incidentally gay couple, and also elsewhere in the world.The outrage at the EastEnders' kiss led to “tabloids… screaming, they outed my partner, we had bricks thrown through the window” (Brooks 2003). On American television, there was also the beginnings of queer representation. One such was when CBS included a gay storyline in their CBS School Break Special series entitled "What If I’m Gay" (1987) in which a typically masculine football player is outed by his friends after finding gay pornography in his bedroom. The intent of the series was to address issues facing high school aged teens; other topics also included date rape. This shows that gay characters were becoming more accepted on prime-time television, particularly non-stereotypical characters such as jocks. This raised awareness of young people identifying as gay as it gave them the opportunity to see an honest representation of coming out.

Section 28 of the Local Government Act (1988) was a "prohibition on promoting homosexuality by teaching or by publishing material." It stated that "a local authority shall not (a) intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality; (b) promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship." This shows that even though there was more social acceptance, politically LGBTQ+ rights and relationships were still considered unacceptable and taboo. It stemmed from the widely held belief that gay relationships were not valid or acceptable, in particular around young children due to the idea that such relationships were "perverted." Section 28 was not repealed until 2003 and some have argued that its influence deprived a generation of homosexual education and is still felt today in the lack of inclusive sex and relationship education in schools today. At the time the “importance of Section 28 was not in any direct repression; it was never actually used to prosecute any local authority. It was just the atmosphere it created. It gave the impression that we were officially, government certified, lesser people” (Appendix 2). This suggests that the law furthered the acceptability of homophobia or neglect to challenge homophobic attitudes. However, as often happened in the 80s, the intention of the law was lost to the solidarity of the minority groups: “the opposition to it was the opposite of what the government wanted. Instead of going away, the anger exploded and put lesbian and gay rights campaigns on every front page, and every news broadcast. By existing it gave a coherence and a unity to the L and G movement that it had rarely had, before or since” (Appendix 2). This is a trend that can be seen in the attack on the miners as the persecution of the working class caused people all across Britain to come together in solidarity and support.

The 1980s saw a development in queer communities and culture. The popularisation of gay pubs and clubs gave the opportunity for queer people to meet up; however, the growth of the queer community and the introduction places such as the London Lesbian and Gay Centre (LLGC) caused issues to arise that may not have been considered before such as the inclusion or exclusion of BDSM practitioners and bisexuals. When the London Lesbian and Gay Centre opened bisexuals and practicers of BDSM were banned; BDSM practitioners were banned due to violence and the use of Nazi regalia, bisexuals were banned as it was felt that lesbians would be sexually threatened by bisexual men (Clews 2017). The discrimination of these groups was overturned in a meeting on the 9th of June 1985; however, some groups still felt excluded from the LLGC and the queer scene in London. One such group of people of colour identifying LGBTQ+, the LLGC was described as "majority white middle class" (Burgess 1988) and "predominantly white, predominantly male." This sense of lack of belonging led to the creation of the London Black Lesbian and Gay Centre, which invited queer people of "First Nation/Third World" descent. (Clews 2017). The LLGC was only open less than a decade. This short life has been attributed to many things, but primarily how amateur (Power 2016) the organisation was was the ultimate reason it failed. It was intended as the "jewels in the crown" of the labour administration (Vice 2016); however, this meant that it was not provided with high priority in terms of training staff. Some ex-members of the club are of the opinion that "if it had opened a little later it might have lasted longer and been more successful" (Blennerhassett 2016). This suggests that cultural reform at the level being attempted was too soon and too fast. One could suggest that the significant events and movements of the 80s only really began to have a greater impact in later years.

The 1980s was the decade of the production of many queer focused newspapers and magazines, one of the most prominent and holding the greatest longevity of these being Gay News/ Gay Times. In 1972, Gay News was not successfully prosecuted on the basis of obscenity due to a photograph of two men kissing appeared on the cover, then later was prosecuted successfully for "blasphemous libel" (Clews 2017). This shows that as queer communities were growing, acceptance was not increasing at the same rate. This could suggest that people were of the belief that sexuality was private and homosexuality should not be flaunted in general society. Gay publications such as Gay Times (the 1984 replacement for Gay News) were directly targeting gay men and unapologetically excluding lesbians. This continued until the publication of Diva, the "sister magazine" to Gay Times, a decade later (Clews 2017). The importance of gay media, such as Capital Gay and Gay Times, to queer communities in the 80s cannot be underestimated as it was “very important because its pre-social media that print media was really the only means of communication. Capital Gay was a good little newspaper it was a commercial newspaper it really punched above its weight a little bit in that it wasn’t shy about being political and being activist in that sense” (Appendix 1). During the Miners’ Strike, information about the work of LGSM was spread through gay media allowing more people to join the cause in solidarity. Furthermore, the media played an important role on the other side of the Miners and LGSM coalition. Due to the manipulated representation of striking miners, there was an internal communication system in which miners from different areas swapped information about the progress of the strike. Mike Jackson recalls meeting some Scottish miners at a rally in Hyde Park: “I remember being Hyde Park and I was having a wander around, it was quite a warm day I remember, and I fell in with these Scottish miners just chatting away and they said, who are you with, and I told them I was with a group called Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners and they said we’ve heard of you. Now you have to remember LGSM was a tiny organisation only 10 or 15 really hardcore main activists, and equally, we were only supporting a very small isolated mining community in the western edge of the South Wales coalfield. And yet the news of that had spread as far as Scotland… I think it would have raised a lot of eyebrows when these Scottish miners first heard, what gays supporting us, so they would have gone through what those in Wales would have gone through understanding why we would be supporting them” (Appendix 1).

This quote from Ray Goodspeed, a member of LGSM in 1984-85, gives an interesting first-hand interpretation on the true nature of homophobic discrimination; “It wasn’t the laws that really did you in; it was social attitudes.” It is often thought that the major problem facing the LGBTQ+ community during the 80s was the repressive laws that prevented equity of rights; however, as Ray Goodspeed suggests, without a change in social attitudes progressive laws had little impact on the acceptance of LGBTQ+ rights and issues. Homosexuality was seen by trade unions and blue-collar workers as a middle-class struggle. This, to some extent, was overcome when LGSM helped with the strike and brought the LGBTQ+ community into the sights of working-class striking miners. It changed the social acceptance of homosexuality as people believed it was something connected to them rather than an isolated issue for middle-class people living in cosmopolitan cities such as London. The attitudes towards masculinity and homosexuality in the valleys were traditional and stereotypical. Such attitudes were described by Christine Powell, a resident of the valley helped by the London LGSM group, as "In the valleys, men are men, and women are glad," meaning that hypermasculinity was seen as correct whereas effeminate men, as many gay men are stereotyped, were not accepted. However, these attitudes changed during the Miners’ Strike as the insular communities of the valleys began to interact with the cosmopolitan Londoners in LGSM. This allowed miners to see that gay men were not all that different from what they were used to. When other mining communities began to learn about the work of LGSM there was a spread of progressive attitudes. One could argue that there was an unequal progression in acceptance. It was to some extent a power struggle between people’s personal ideological opinions and the official governmental line. This can be seen in the introduction of Section 28 and the opposition against it. The unequal progression of ideological change and political change suggests that events such as the Miners’ Strike which advanced the ideological change in more traditional communities.

It could be argued that major advances in the area of queer rights neglected and excluded lesbian, gay, and bisexual women. A trend of the exclusion of lesbians from increasing or decreasing queer acceptance can be seen throughout historical laws which specifically targeted men, such as the criminalisation of anal sex (typically known in law as "sodomy" or "buggery"). For example in 1533, King Henry VIII passed the Buggery Act 1533 making any and all male-male sexual activity punishable by death (Smith and Hogan 2002). This shows how throughout history, there have been distinctions made between female homosexuality and male homosexuality. Such distinctions arguably slowed the progress made to increase acceptance of the queer communities as often lesbian acceptance has come at a later date. This may be, in part, due to the taboo of female sexuality either lesbian or straight which was held in particular until the sexual liberation of the 1960s. The growth of a specific and somewhat separate bisexual community also began to grow. The first "Politics of Bisexuality" conference was held in London from the 8-9th of December 1984. It had a small turnout of 40 people but it was considered as very successful (BiMedia 2005). It was open to those identifying as bisexual to discuss issues pertinent to them. This further proves the dissent among the bisexual community at their exclusion from general discussions about homosexuality. The second "Politics of Bisexuality" Conference was held at the London Lesbian and Gay centre which had just prior banned bisexuals from their premises. The event has continued to this date since the first conference in 1984. This suggests that although there were many significant advances during the 1980s, there continues to be divisions and lack of acceptance in society concerning the place of bisexuality. This further evidences the argument that the journey to homosexual equality was slowed by the distinctions made between different factions of the LGBTQ+ community both by themselves and others in society.

In conclusion, the 1984 Miners’ Strike did have a significant impact on bringing awareness of the gay community and their struggles to isolated communities outside of the cosmopolitan cities. Widening the base of support for was significant as it brought in more active supporters shown in the block vote from the National Union of Mineworkers at the 1985 Labour conference to include LGBTQ+ rights into their manifesto. However, the work of LGSM during the Miners’ Strike was not some of the earliest activism but rather it springboarded from the activism of the 1960s. The greatest significance that the Miners’ Strike and LGSM had was to bring LGBTQ+ rights and struggles to a personal issue in places that it had not been considered. Most of the work of LGSM was with small groups and had its greatest impact on small areas rather than on a national scale. Arguably, the most significant factor in the increase of awareness and acceptance of queer persons was the advances in television. It has been seen since the earliest invention of entertainment television that people are heavily influenced by the shows they watch and the idea of the hypodermic needle theory suggests that audiences are passive in their formation of opinions based on media texts. Due to television and film as a mass entertainment form that was viewed by people every day the representations of homosexuality and queerness became more widespread, reaching communities that may have felt distanced from LGBTQ+ issues.

Analysis of Sources

Much of the significant research for this essay was explored with two particular books as the starting point. Colin Clews’ Gay in the 80s and Tim Tate’s Pride were vitally important to a greater understanding of the situation in the 1980s for LGBTQ+ persons. The book Pride was written in conjunction with the 2014 film of the same name (dir. Matthew Warchus); the format of the book is mostly comprised of first-hand interviews with key members of LGSM such as Mike Jackson, Reggie Blennerhassett, Colin Clews and many more, also, there are interviews with citizens of the Swansea, Neath and Dulais Valley. This is a highly valuable source for this study as due to being quite a niche area of study it gives information that can only be found by working directly with those involved. There is also discussion of general information surrounding homosexuality and society in the 1980s. This book gave the opportunity to research further into areas of change such as the introduction of Section 28. Its greatest value, however, lies in its ability to give personal experiences which cannot be expressed through legislation and second-hand information. This gave insight into how the factual information such as laws passed had a direct impact on LGBTQ+ people. One limitation of this as a source is that it is a micro-history written from the point of view of a very small sub-group of the LGBTQ+ community. This limited how far it could be used to explore the greater impact of the Miners’ Strike such as its impact in other areas of Britain. However, it was overall invaluable in researching for this essay.

The second book, Gay in the 80s, gave details on many aspects of life in 1980s United Kingdom, Australia and America. This added value as it allowed for comparisons to two countries that experienced the 80s without the Miners’ Strike. It was this that was significant in drawing the conclusion that the strike’s significance was undermined by the general changes and advances being made in society. Similarly, this was valuable as it was written by a member of LGSM and therefore had information on the specifics of LGSM’s work in the greater context of gay Britain. Being able to compare media in America and Britain showed that in many ways, society was advancing without the Miners’ Strike and televised media was becoming more accepting of homosexuality. One limitation of this source was that it gave a good overview of the general society of the 80s but in some instances, it glossed over key details.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.