Polling Putin's Problems with AI

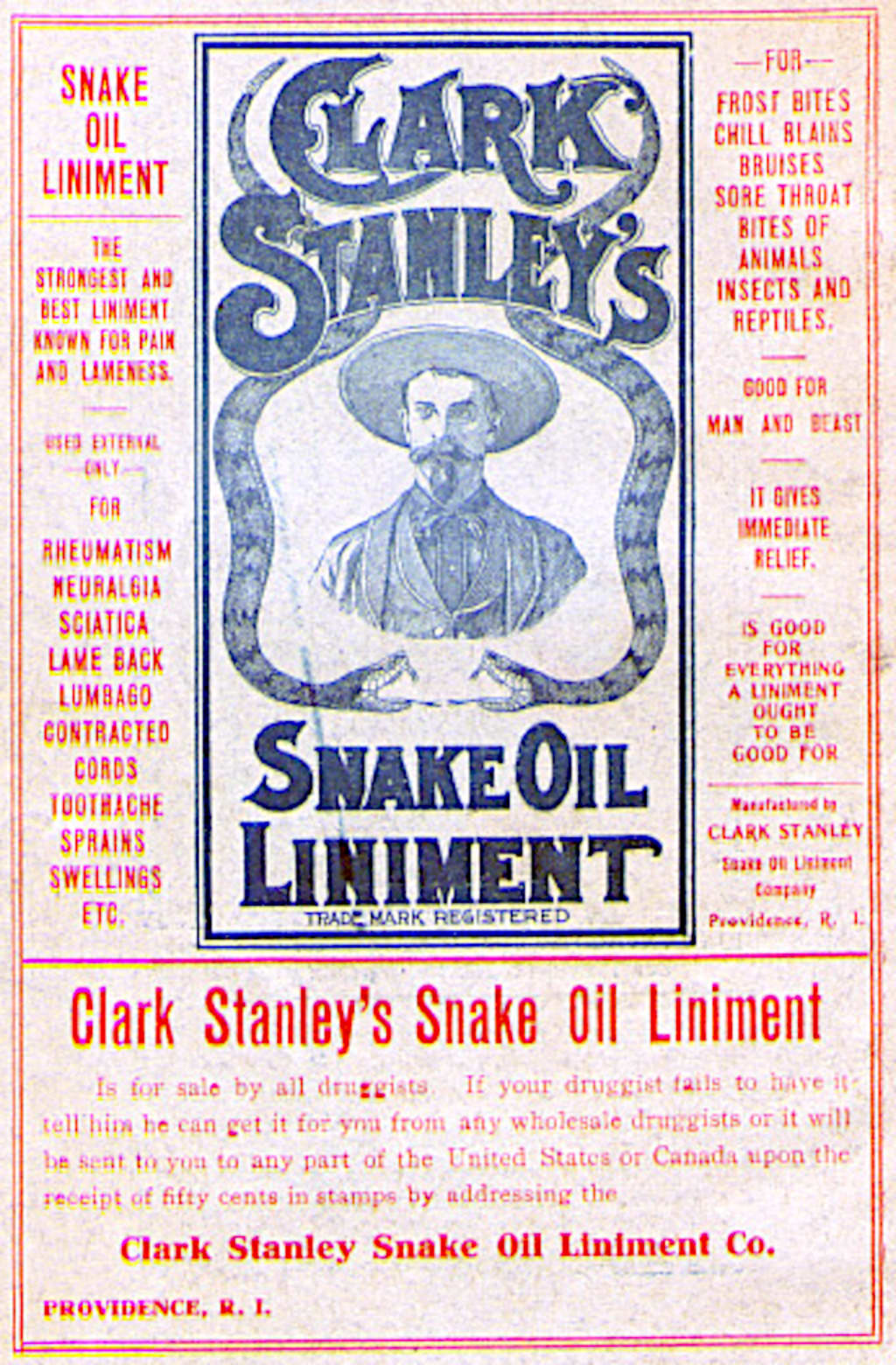

It sounds like snake oil, but it may have some validity

I was intrigued by a story about how Artificial Intelligence can assess Russian public opinion — and yes, it sounds like snake oil, but…

It’s called sentiment analysis.

Not sentient — it’s AI and that’s not sentient. Yet.

For the past year, the Center for Strategic and International Studies has worked with FilterLabs.AI, a Massachusetts-based data analytics firm, to track local sentiment across Russia using AI-enabled sentiment analysis. So says the story in Politico.

And that got me wondering. The first obvious question is how in hell can they ‘track local sentiment across Russia’ ?

Sentiment analysis

Sentiment analysis (also known as opinion mining or emotion AI) is the use of natural language processing, text analysis, computational linguistics, and biometrics to systematically identify, extract, quantify, and study affective states and subjective information. (Wikimedia)

When I got my marketing qualifications and worked in the sector too many years ago, the nearest we got to this was focus groups and regular customer opinion surveys. There was no such thing as digital marketing apart from early email campaigns at 4,800 bps.

Things have certainly moved on. And not only in marketing.

Now we have a war underway with drones, cyber and social media in addition to all the usual weapons and tactics…

…and AI, on several fronts.

But the Wikipedia entry for ‘sentiment analysis’ still comes back to questions — and the construction of questions for market/opinion surveys is both an art and a science. Basically, you can get any answers you want if you phrase the question in the right way — and if you choose your respondents.

It really is snake oil.

If however, you are seriously trying to assess the mood of the Russian peoples (there are more than just White Russians) then you can’t mess about with semantics.

And you don’t bother with questions.

These are meta surveys of Russian sentiment.

AI surveys.

Artificial intelligence?

By using AI to analyse social media posts, news articles, and other sources of online content, influencing and debate, the AI’s sentiment analysis algorithms can identify patterns and trends in public opinion, and provide arguably valuable insights into the issues that are most important to those who express themselves digitally.

That’s my bolding — I’ll come back to that a bit later.

And we come back to the basics of AI. How good is the training data?

In the context of this story, and the recognised reluctance of Russians to be truthful in such a frightening society, then how can we attach any real significance to the results?

Another concern is the potential for bias in the algorithms used for sentiment analysis. Like all machine learning algorithms, sentiment analysis algorithms are only as good as the data they are trained on.

That’s the training data issue. Times two.

Polling methodology

The Politico story tells us that:

Standard polling often concentrates on population centers including Moscow and St. Petersburg, which can skew national averages. Outside of those major cities, a more negative picture emerges. Our analysis shows that the Kremlin is increasingly unable to control public sentiment outside major cities with national propaganda.

Who’s doing the polling?

No one.

It’s a meta analysis process, carried out by an AI system running bots.

Propaganda waves

The AI system of Filter Labs is trawling and scraping all available online documents, social media posts, Telegram channels and the like and analysing the text.

It is looking for trends.

According to the ‘pollsters’, the propaganda churned out by the Kremlin appears to follow ‘waves’.

Kremlin propagandists work iteratively, piloting slightly different messages successively and rolling them out in waves when their analysis signals that they are needed. Since the invasion, Russian state-sponsored propaganda waves elevated public sentiment toward the war for an average of 14 days across all regions and topics. — Politico (ibid)

Filter Labs has (as of 26 February 2023) concluded that Moscow’s local media is great deal more variable than the Russian national media is in general.

Also, they took the far eastern Republic of Buryatia as a sample area outside of White Russia. Many draftees for the war have been drawn from there as part of Putin’s plan to keep the war pain out of the big cities by using the expendables from the backwoods.

And yes, Buryatia really does exist — it’s not a republic out of a Marx Brothers film.

Putin’s regime less able to control the narratives

Filter labs presents data which appears to show that Putin’s regime is growing less and less able to control the narratives about the war. That was in 2022.

There are 4 distinct narrative boosts, which decrease in effectiveness as the war progresses. The last two [propaganda] cycles return to localized minimums much more quickly, as the overall trend continues to grow more negative.

That means that the local people are becoming more sceptical about the Kremlin’s messaging at a national level.

The natives are becoming restless, it seems.

Conclusion

AI-enabled sentiment data analysis can provide a window into how Russians feel and how fickle public sentiment is.

And that pesky bit that I bolded earlier — ‘those who express themselves digitally’.

It’s not a random sample of Russian public opinion — and that’s not usually good for high confidence in results being generally applicable.

However, if the online sentiment moves negatively for Putin, then that’s hardly likely to be something that his troll farms have worked at, is it?

If online sentiment moves positively, then we’ll read that with a higher degree of suspicion.

If the results from Filter Labs and Center for Strategic and International Studies are reliable then…

This poses internal threats to Putin’s legitimacy and thus his power. It also signals an inherent mistrust of state institutions that will be part of Russian society — especially outside of Moscow — well after Putin’s reign ends, whenever that may be. — politico.com

***

Canonical link: This story was first published in Medium on 28 February 2023

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.