On Human Misunderstanding

An account of political polarization

By way of preamble, I'd like to point out that this piece is motivated by the invasion of the Capitol building by right-wing protestors while Congress was in the process of certifying the results of the 2020 Presidential Election.

I am concerned here with understanding how this came to pass. There are at least two ways of addressing question of growing political polarization. The first is with specifics from the front lines over the last four years: the fomenting of (violent) right-wing ideology by the president and other Republicans, the spreading of bad-faith evidence-free claims of election fraud, the undermining of traditional political norms and institutions. The second approach, which I pursue here, is to abstract away the particulars of our current political climate and look at the general features that make modern citizens prone to this level of polarization. Another popular angle is to look at structural features of the American political system that perpetuate and exacerbate the ideological divide.

My objective is to give an account of how we, the agents within the political system, are susceptible to polarization in the first place. To give a breakdown by academic discipline: I consider the detail-oriented account of political polarization to be the job of journalists and historians. They're the ones that spell out the proximate causes of our current predicament. On the other hand, the structural account is usually given by political scientists and economists. But the often forgotten agent-oriented view falls within the realm of cognitive science and sociology. This neglected perspective, divorced from historical and structural contingencies, spells out how human minds, individually and collectively, operate under political pressures.

Political Ideology

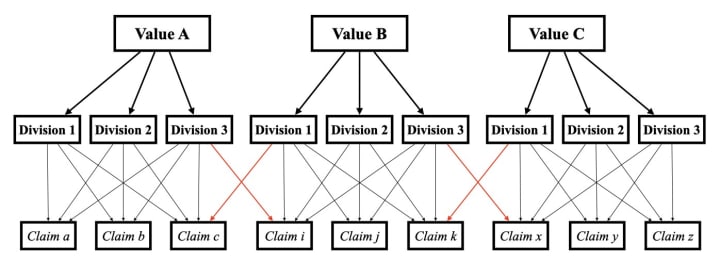

What is an ideology, political or otherwise? Broadly speaking, it's a series of claims about what we think is proper to do based on our values. Values are the ultimate justification we give when asked, "Why do you think x, y, and z?" Broad values - like, Equality, Liberty, Fairness - can be subdivided into more specific principles given a particular domain of experience; that subdivision can rationally give rise to distinct claims that are justified in terms of the value structure above. This is outlined in the diagram below which includes red arrows representing tension or conflict between subdivisions of values held by a single person. These conflicts are key to resolving the entire structure of a person's ideology because the friction between values are settled by an individual's preferences or personality, by the weight they give to each value. The key role of personality differences in determining the overall shape of an ideological model is part of the individual differences approach to understanding the psychology of polarization. It's important to note that social context plays an important role in shaping an individual's preferences; it's not all a matter of an individuals "innate" personality.

This model is clearly an idealization of how human minds try to make sense of the world given the values they hold. While it's true that our brains probably don't actually operate in this manner, this is what we think we're doing. Anybody engaged in rational deliberation and honest conversation is trying to make their opinions cohere logically given the values they hold and shifting the weight they give to certain values given new circumstances they encounter. Coherence is logically desirable, so how does this contribute to political polarization?

The problem is that the realm of claims that fall into the political category has expanded tremendously. The political is no longer constrained to issues regarding military spending or environmental policy; there's a tinge of politicization to everyday life activities like where people shop for food, what clothes they wear, or the coffee they drink. Consequently, there are more and more claims that need to be reconciled with the value structure and this becomes an increasingly challenging task for any one mind. Daunted by the complexity of trying to determine how problematic a previously apolitical matter is today, it's rational to adopt the behavior of people around you who mostly agree with your values. There is nothing wrong with deferring to those in our social circle who are better informed about a particular issue; they may have a coherent account about newly politicized matters. The real problem is that this is actually rational and coherent; the problem is that it is possible to give an account of how the silliest claim fits into an otherwise respectable worldview. Truthfully, a fundamentalist can be perfectly coherent in his claims; he might be mad, but he is coherent.

Reality Curation & Probabilistic Causation

So far, I have described how an individual mind might cope with our increasingly politicized society and the political signaling from the trusted few in their immediate social circle. While it's possible to find correlations between certain cognitive traits and the likelihood of adopting extreme political positions, these are not enough to accurately predict if an individual will become radicalized. Since it's not yet possible to analyze political extremism at the individual level, it's necessary to take a step back and look at a larger sample - a population within the country, or the entire society. Once we zoom out to this higher level of complexity, we need to dispense with the notion of deterministic causality (A always causes B) and move to the realm of probabilistic causality (A increases the probability of B occurring). To be more precise, it is not possible to say that a particular perturbation in the society causes political extremism in a subset of the population, but we can say that said perturbation raises the probability of somebody becoming radicalized. And of course, the perturbation of our generation is social media and its effort to accurately cater to our needs and preferences.

Here it's important to clarify the now trite proposition that social media is responsible for the increase in political polarization. It's not possible to say that the reality curation facilitated by social media causes radicalization for the reason outlined above; we can only say that it increases the likelihood of it happening in the population. From a statistical point of view, social media causes polarization in the same sense that smoking causing cancer. Therefore, when people sign up for social media platforms, their initial political preferences are determined and catered to by accurate recommendation algorithms. Within the platform, a steady stream of increasingly extreme political views will appeal to a subset of users. At every step of the process, there is rational connective tissue from the user's current political view and the slightly more extreme one they're being exposed to. This can continue until somebody's worldview becomes extreme but still remains coherent; it may in fact become more coherent as it becomes more extreme while only making the slightest contact with reality.

Tribalism All the Way Down?

Some might wonder whether this is just a detailed account of modern tribalism. The term here is used in the more lax sense closer to "group affiliation" as opposed to any technical meaning of the word "tribe." While I don't doubt that individuals adopt the ideas and behaviors of those around them because they're part of their trusted social circle (as I mentioned above), I don't think this ideological heuristic is a useful way of understanding the problem. What is actually troubling about this situation is that it's possible to give a rational and coherent account of the most tribal position. Even if the most extreme members of either group can't articulate a convincing justification, they can construct one given enough time.

To argue that nobody could possibly, in good faith, hold the positions of the people involved in the storming of the Capitol building is simply to argue from incredulity. How can one be certain that there is a perhaps tortuous but still coherent worldview that justifies the extremism witnessed on January 6th? Because over 74 million people, just under 47% of all votes cast in the 2020 election, went to Donald Trump after four years, after his style of governance was clear to everyone. This large swath of the country includes everyone from the Heritage Foundation to QAnon and there is connective tissue between them two that justifies the madness of the latter at the expense of the former. Even if you think that the violent extremists that interrupted the Electoral College vote certification have nothing of value to say politically, that they're simply confused or mistaken, there are people that populate every gradation of the the ideological spectrum right up to where these insurrectionists exist.

A Path Forward

Given that I have repeatedly promoted the idea that even the most extreme political positions can find a justification in a cogent worldview, it won't be surprising that I don't think there's a rational solution to the problem of political polarization. To be clear, I don't think rational discourse, the sharing of opposing views in good faith, is going to do much to reduce extremism. The optimistic view that if only we spoke to each and reached across the aisle, then polarization would abate is probably mistaken. In fact, there's some evidence that exposure to opposing political views on social media can increase partisanship. The reason is that the problem is not about proper reasoning or missing information; so if the problem isn't with the prefrontal cortex, we have to find another route to reconciliation.

At an individual level, the best any one of us can do is help depoliticize everyday activities, to simply not engage or promote political consumerism. One step further, if you have friends of a different political leaning, it's best to not highlight ideological differences and build rapport over other shared interests. The goal here is to shrink the realm of the political and restrict it to matters of policy which should be settled with open debate and at the ballot box. Although the personal is political, going forward it might be better to not take everything that's political so personally.

At a societal level, it's necessary to rein in online extremism in various ways. To prevent further radicalization, it should be possible to exclude political content from recommendation algorithms. This can either occur as a private initiative from social media companies or via carefully crafted legislation. Targeting the algorithms as opposed to the actual content might bypass censorship concerns since this would only curtail the automated distribution of extreme content while not explicitly banning it. It's incredibly tricky and challenging to come up with a definition of "ideologically extreme" content that can be reliably implemented. But this is the challenge of our time, the development of responsible digital infrastructure - a challenge, that given the shocking events of the past week, we can no longer afford to ignore.

As a final note, I'd like to add a passage from Richard Crossman's introduction The God That Failed, a collection of essays about Western intellectuals' disillusionment with communism. I think it offers some insight into how otherwise intelligent people can become enamored of a worldview and accept it even when confronted with its public and horrifying failures. Here's the quote:

"Once the renunciation has been made, the mind, instead of operating freely, becomes the servant of a higher and unquestioned purpose. To deny the truth is an act of service. This, of course, is why it is useless to discuss any particular aspect of politics with a Communist. Any genuine intellectual contact which you have made with him involves a challenge to his fundamental faith, a struggle for his soul. For it is very much easier to lay the oblation of spiritual pride on the altar of world revolution than to snatch it back again."

About the Creator

Kevin Erazo Castillo

Graduate student (permanently, it seems). Scientist by day. Writer by night. Gay at all times 🌈 I post funny essays, opinion pieces, and some favorite recipes.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.