Missing The Debates? Don't Feel Bad

Massive Media spectacles are hardly debates

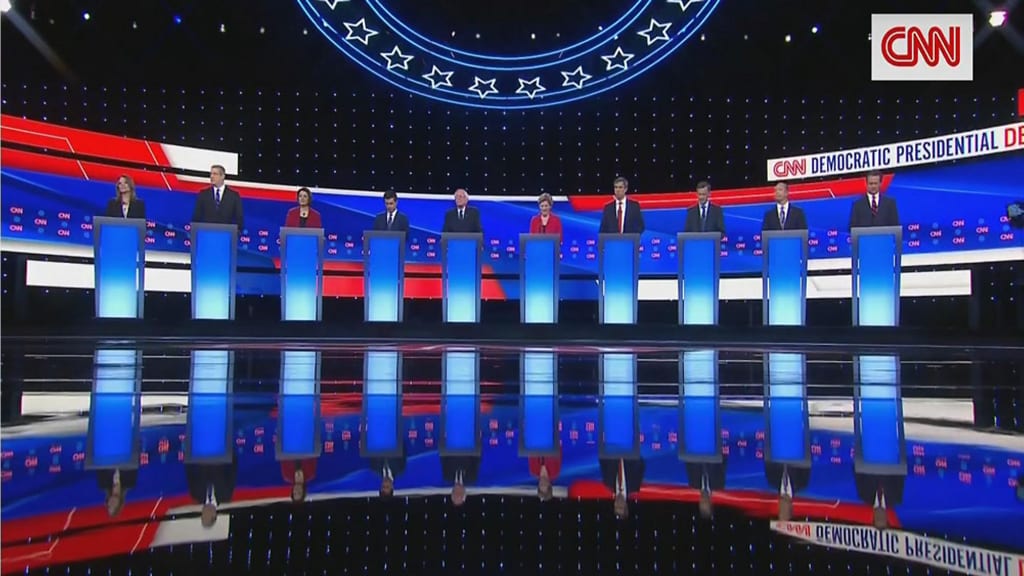

It feels pretty bad to be interested in politics but not want to sit through these three-hour candidate debates that keep cropping up. Featuring ten candidates—three or four you actually have heard of—these events purport to be an honest examination of the issues facing the United States in the 2020 Presidential election.

I felt pretty bad about not watching the debate last night. I'm supposedly a rhetorical scholar, and someone who studies and writes about political debates. I was even on MSNBC discussing the run-up to the McCain-Obama debates. But these spectacles are not something we should feel bad about missing. In fact, the bad feeling comes from some very clever media manipulation that is primarily designed to sell advertising space, and enrich MSNBC, CNN, and whoever else decides to host one of these monstrosities.

Let's do a little semantic work to ground my point of view here. What is a debate? What comes to mind if you hear the word "debate?" Most of us will imagine at least two people, locked in disagreement, exchanging heated words with one another about how they are right, and their opponent is wrong. Some might imagine a moderator who tries to keep the debate from becoming too personal. And very clever readers will imagine that there's an audience there, taking it all in, deciding and judging the things that are being said by the debaters. The speakers will use facts and statistics, quotes and news stories as often as they can, and they will also share narratives, experiences, and other things that the audience finds familiar and typical. There are most likely time limits and turn-taking during the speeches, they're not a free-for-all of shouting. And at the end, each speaker should be able to sum up their position, and tell the audience what it is they should do with the events that transpired during the debate.

The most important thing about this imagined debate model is that there is an audience, and everything is done for the benefit of the audience to determine what they should do, and what they are going to do with the debate. The time limits, the questioning, the engagement is all meant to help the audience decide something. As rhetoricians put it, the audience should be asked to think, feel, do, or believe something. It might or might not be counter to what they think already. And it is surprising to most people to realize that rhetoric is often doing the work of reminding you what you already believe. It's very rare indeed when a speaker strongly states a belief that is contrary to what the audience thinks, and they all happily agree in the light of the facts. This is a fantasy.

The reality is that debates are audience-centered. That is, if you want to be successful, you must work to align yourself with the views, beliefs, life-experiences, and culture of the audience. You don't have to agree with it, but you must incorporate it in some way. Something must be there to help the audience see you as someone worth listening to.

It's a lot of work to get the audience on your side, and it's eight times as difficult when you have that many more opponents than you usually would. But this assumes the debate is normal, and audience-centered. These debates are media-centered.

A media-centered debate is designed, not for the audience, but for the network. It's designed to make you start watching it, and keep watching it. Quick speech times, quick cuts to reaction shots, bouncing around through topics that would take months to explore, and making sure that the moderators, who are more celebrities than journalists, get most of the time to speak, are just a part of how it's set up.

Sponsoring the debate, broadcasting it, preparing it, and getting the consent of the candidates to appear in it is a lot of work. The media company views this primarily as an investment. All investors want their money to at least double—but if it can go even further than that, they are all for it. Media-oriented debates are arranged to do this at the expense of the audience. They are arranged to be content-generating machines.

With 30 second statements and 15 second rebuttals, or whatever the crazy rules are, candidates are motivated to provide very short, very sharp one-liners. Since exchanges will be shut down quickly by the moderators, they have to happen fast. This is explained by saying there's a lot to cover, but the reality is that the media company wants to create sound bites to play and replay all day on their network, multiplying their investment in one show into multiple shows. Short clips of sharp statements that sound good is a great way to ensure that we keep watching, even if we watched the full debate.

The debate is also structured like a game-show, which allows for endless journalistic interpretation to fill shows throughout the 24 hour cycle. So-called "Fact checking" keeps the journalists busy creating content based off of one or two things a candidate might have said in a hurry to make the most of their 60 seconds of airtime. This is another great use of money already spent, where one candidates mistake—struggling to adapt to a ridiculous battery of rules—can become the topic of an entire half hour of programming and advertising revenue.

What does it mean to have a debate? We use the phrase "have a debate," but it's very strange from the standpoint of grammar. Is debate an object, something to possess? Is it like a party? We don't "throw a debate" but we can "have" one. Does this imply some ethics, some ownership of our actions? If we decide to have a debate, we must decide what it is we are "having." And the best debates are those that "have us." This means that the debate is oriented toward the audience, whoever that might be, and that the participants are allowed to exchange views with one another on issues that are contextualized for the audience. It would be interesting to see a candidate speak directly to the people in the audience, in the city they are in, about their issues, and work to connect us at home with it. This is the work of rhetoric that is not taught—the work of identification. Rhetoric's function is to help us see one another as working toward the same goals, seeing the world in a similar way.

Until these events become audience-centric—the governing principle of the study of persuasive oratory since the ancient world—they might not be worth watching. Of course, they are very entertaining, but the trade off is with your time where you could be doing something valuable to you. And it's up to our candidates to discover what we value, and speak to it in hopes of fostering identification. Not sure if I can suggest to you to watch these events, but if you do remember: they are not crafted to help you, they are crafted to use you to create wealth for the media companies.

About the Creator

Steve Llano

Professor of Rhetoric in New York city, writing about rhetoric, politics, and culture.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.