How Québec’s Nationalist Movement Became the Spearhead of Racist Militancy

From A Liberation Struggle To A Fight For Whiteness

Then at the vanguard of social justice struggles in Québec, the nationalist tendency is now one of the strongest components of the racist right wing in the province. It has almost completely abandoned the fight for political and economic emancipation to concentrate on cultural politics, fighting against immigration, liberty of religion and other topics also cherished by the fascist right. While some would easily condemn nationalism in itself, going back into the history of Québec’s fight for independence seems necessary to understand how Québec’s liberation movement transformed itself into the reactionary force it is today.

Québec’s independence struggle goes back to an old tradition of anti-British revolts like the Patriotes’ rebellion of 1837-1838 or pamphleteers’ writings from the early 1900s. Its golden age was situated in the 60s and 70s when groups of many horizons—from conservatives to communists—led the struggle up to a referendum in 1980, which wasn’t victorious.

The large array of pro-sovereignty groups was definitely left-leaning: at the far-left was the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ), which had a complicated and utterly action-packed history. With ties to the Black Panthers, Algerian revolutionaries and Palestinian freedom fighters, the FLQ relied on guerrilla tactics—robbing banks, kidnapping government members and blowing up many symbols of British imperialism. Also in the left hemisphere was the Rassemblement pour l’indépendance nationale [French for "Rally for National Independence] whose leader sometimes quoted Ho Chi Minh, used the term “socialist” without shame and fought side-by-side with unions against the Anglo-Canadian bourgeoisie. Less well known were other left wing groups like the Action socialiste pour l’indépendance du Québec, Québec’s Socialist Party, or Andrée Ferretti’s Front de libération populaire [French for People's Liberation Front], all influenced by Marxist writers such as Frantz Fanon and Albert Memmi.

However, there where other groups that did not want to be associated with the left-wing of the movement, for example the Alliance Laurentienne—a catholic party of intellectuals—or Gilles Grégoire’s Ralliement national—a populist party formed by proponents of the social credit theory and dissidents of the Rassemblement pour l’indépendance nationale who did not want to be involved with a party run by an agnostic, leftist homosexual. The Ralliement national would finally merge with the Mouvement souveraineté-association [French for Sovereignty Association Movement]—a newly formed group with René Lévesque as its leader. Lévesque—a young rising star in left reformist politics—had just left the Liberal Party because its establishment refused to back Québec’s plea for independence. He then went on to create the Parti Québécois (PQ) in 1968.

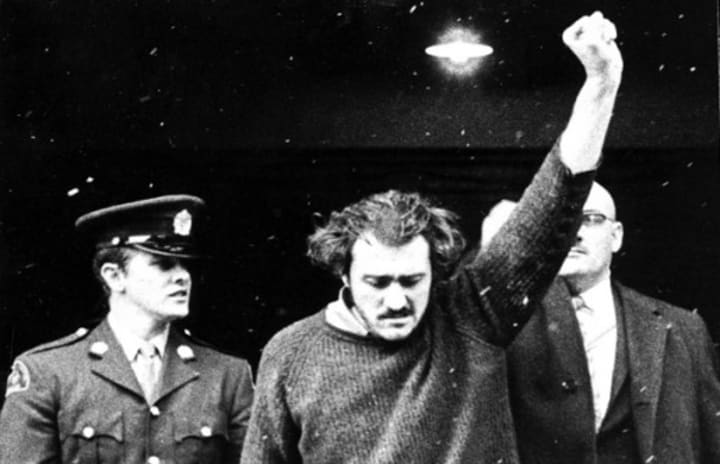

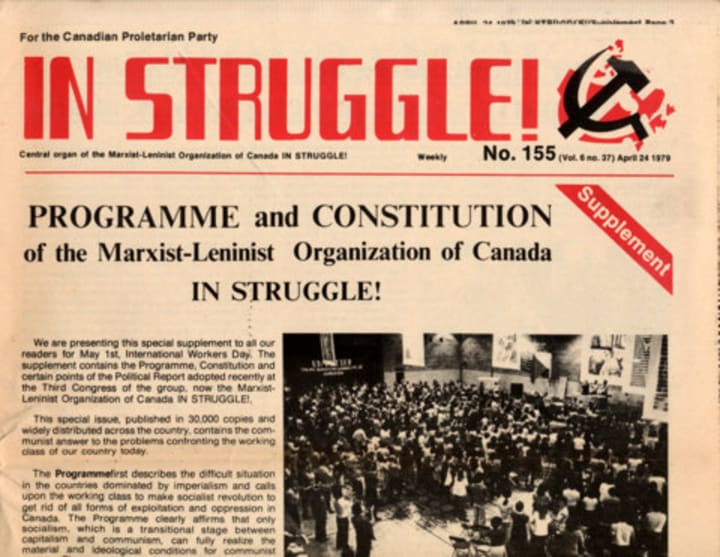

This new party would be the main vehicle for the official and electoral struggle for Québec’s sovereignty. Even though Lévesque’s point of view on the national question was pretty moderate, as he favored the negotiation of a new deal with Canada’s government instead of seceding right away, many members of the radical left joined the Parti Québécois. Formerly living in clandestinity because of his involvement with the FLQ, Pierre Vallières publicly joined the side of Lévesque’s legal struggle, as Pierre Bourgault—leader of the Rassemblement pour l’indépendance nationale—already did, enjoining the 14,000 members of his party to do the same. For many intellectuals and activists, the Crise d’octobre [French for October Crisis]—which saw the Canadian army invade the streets of Québec and jail almost anyone who actively supported Québec’s independence—was a traumatic event, leading them to abandon radical militancy and join social-democrat struggles. Groups who advocated armed struggle for national liberation began to disappear as their members joined either anti-secession Maoist groups like In Struggle!, led by the former FLQ member Charles Gagnon—or reformist parties and unions.

The PQ went from a marginal party—as he won only seven seats during the election of 1970—to forming the government in 1976. This electoral victory led to a referendum in 1980 which resulted in a win for the federalists, since 59 percent of the voters chose the No option. The referendum question illustrated well the moderate turn of nationalist politics, as it was a nuanced and hesitating text. Against the left-leaning wing of the party, led by Jacques Parizeau—who had been throughout his life both sympathizer of a communist party and banker—opposed it, Lévesque and his party asked the following :

Le Gouvernement du Québec a fait connaître sa proposition d’en arriver, avec le reste du Canada, à une nouvelle entente fondée sur le principe de l’égalité des peuples ; cette entente permettrait au Québec d'acquérir le pouvoir exclusif de faire ses lois, de percevoir ses impôts et d’établir ses relations extérieures, ce qui est la souveraineté, et, en même temps, de maintenir avec le Canada une association économique comportant l’utilisation de la même monnaie ; aucun changement de statut politique résultant de ces négociations ne sera réalisé sans l’accord de la population lors d’un autre référendum ; en conséquence, accordez-vous au Gouvernement du Québec le mandat de négocier l’entente proposée entre le Québec et le Canada ?

[French for: "The Government of Quebec has made public its proposal to negotiate a new agreement with the rest of Canada, based on the equality of nations; this agreement would enable Quebec to acquire the exclusive power to make its laws, levy its taxes and establish relations abroad—in other words, sovereignty—and at the same time to maintain with Canada an economic association including a common currency; any change in political status resulting from these negotiations will only be implemented with popular approval through another referendum; on these terms, do you give the Government of Quebec the mandate to negotiate the proposed agreement between Quebec and Canada?"]

Although the main voice for the nationalist camp in Québec’s media was the PQ’s, many initiatives were carried by other supporters of the Yes option. The referendum campaign saw the implication of members of the Communist Party of Québec, of the Combat socialiste’s Trotskyists and other far-left activists. Another part of the left opposed that option, however; for example the Nouveau Parti démocratique du Québec—a marginal social-democrat party who supported the unity of Canada.

After the defeat of the Yes option, René Lévesque and Claude Morin, an informant for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, proposed what they named "Beau risque" [French for "the noble risk]. This would lead the PQ to support the Canadian Progressive Conservative Party—who proposed a mix of free market and conservatism—since its leader Brian Mulroney promised to amend the Canadian constitution to give Québec a special status in it. Québec, as a matter of fact never signed the Canadian constitution since it was forced upon the province by an agreement between all the other provinces’ premiers, the Canadian premier Pierre-Elliot Trudeau, the British House of Commons and the Queen of England. Many members of the PQ—including progressive MPs like Jacques Parizeau, Camille Laurin and Louise Harel—left the party. The void created by this exodus gave the right wing of the party a more prominent role. Overtly capitalist and anti-union individuals like Lucien Bouchard came to be public figures of the nationalist struggle, leading to the creation of the Bloc Québécois which participated in federal elections as the main representative of the nationalist forces. While advocating left-leaning ideas from time to time to allure their remaining left-leaning base, the Bloc’s staff was mostly composed of right-wing activists that were formerly members of the Canadian Liberal Party and the Progressive Conservative Party.

With an even more moderate Lévesque apace with the right wing Bouchard, the nationalist side never went to propose a deal to the federal government that would satisfy Québec’s population and the other provinces’. Instead, the PQ went on to rule as a candid provincial government, even importing capitalist repression tactics usually withheld as the party was said to have a "préjugé favorable envers les travailleurs" (French for a favorable bias toward workingmen). As 1982 began, Lévesque’s government cut into social programs, tried to lower the salaries of the state employees and went at war with unions, as it voted laws to forbid certain strikes that were supported by a large part of the population. Lévesque would retire in 1985 to see Jacques Parizeau make his comeback and take his place two years later. The new leadership of the PQ then refocused the party around its raison d’être: to liberate Québec from the colonialist state of Canada.

Parizeau worked with his new ally, Lucien Bouchard, until the 1995 referendum, which resulted in a victory for the No option with 50.58 percent of the vote. Parizeau—as promised—retired after this defeat and left the gate open for Bouchard to take the leadership of the PQ. Bouchard, as he became the new Premier of Québec, shamelessly favored right-wing policies by imposing austerity measures : he took stances against unions, reduced the growth of the minimum wage and allowed his friend Paul Desmarais to concentrate even more the media outlets of the province. Nowadays, Bouchard is still a zealot of capitalism. He often accused the Quebecers of not working enough while he—since 2011—had been a lobbyist for an oil consortium, an advisor for the highest paid physicians in the province and a negotiator for a paper company on behalf of the government (he was paid half a million for this last job).

As he went on with his plan to put Québec’s independence on the back burner and concentrate on reducing the state spending by 10 percent, left-wing nationalists, socialists, feminists and alter-globalization militants formed groups that would later merge to create Québec solidaire—a left electoral party who supports Québec’s emancipation from Canada. The PQ’s change of reign in the 2000s would not rehabilitate the party for these numerous activists who disliked the politics of Lucien Bouchard just as much as those of his successor Bernard Landry—a bourgeois par excellence who became Premier in 2001. Leftists fled the party throughout the decade, while those staying in the organization claimed that other parties were only there to ruin the cause of Québec’s liberation since they divided the nationalist vote.

It took up until 2012 for the PQ to be reelected, with 31.95 percent of the popular vote. The student strike which lasted well over 100 days earlier that year permitted Pauline Marois to become Premier, as she supported the student cause and promised to cancel the tuition fees hike that caused the strike in the first place. However, when she betrayed her electorate by indexing the tuition fees, kneeling before the mining industry and selling the Anticosti Island to a gas company, Marois’ support diminished drastically. Bernard Drainville—her minister of Democratic Institutions and Active Citizenship, found the inspiration to wave the false flag of an Islamic menace, reminiscing the 2008 rise of the populist right-wing formation, the Action démocratique du Québec, who then almost won its election with this precise tactic. These straw man politics were to allow the PQ a gain of support from a right electorate normally voting for federalist parties while the young citizens turned toward the inclusive Québec solidaire.

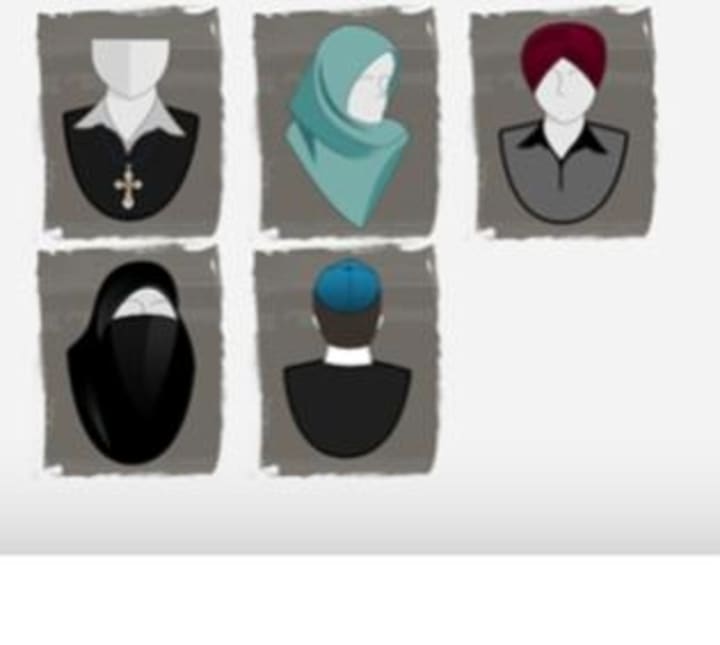

Drainville proposed a "Charter of Québec Values," or, in other words, a law that regulates where and when people—especially Muslims—can wear religious symbols or pieces of clothing that cover the head (with the exception of small Christian crosses). Many supporters of this law—that never passed—would later be members of neo-fascist or anti-immigration groups like La Meute [French for The Pack], Storm Alliance, or the Fédération des Québécois de souche [French for Federation of Native Quebecers]. Among those was also the young Alexandre Bissonnette, a right-wing supporter of Drainville who would kill seven people at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Québec City in 2017. Despite that draft law, which secured them numerous racist allies, the PQ lost 24 seats in the 2014, elections since it had lost the support of non-bureaucratic unions, students, radical nationalists, POCs, Indigenous people, ecologists, and feminists. On an obvious decline, the PQ continued to try to appeal to an afraid population by using a xenophobic rhetoric carried by Jean-François Lisée—a then-communist, now-chauvinist who would become leader of the PQ in 2016.

During that Charter episode, most of Québec’s media (possessed mainly by two companies) went on to unofficially, but conspicuously, endorse an anti-Islam line. The student strike being over, columnists like Richard Martineau, Lise Ravary or Christian Rioux had to find another scapegoat. An already marginalized population like the Muslims was an easy target for racist groups fueled by media propaganda. Pig heads were dropped in front of mosques and hidjab-wearing women were harassed, but many media defended these hate crimes by repeatedly claiming they were only bad taste jokes. Indeed, the hate crimes against the Black and Muslim population in Québec rose from 2014 and onwards according to Statistics Canada.

Having dropped the idea of Québec’s independence to prioritize its populist anti-immigration turn, the PQ lost its members to a more openly xenophobic and capitalistic formation: the Coalition avenir Québec [French for Coalition for Quebec's Future] (CAQ)—a party formed by conservatives with the ex-PQ minister François Legault as its head. In 2018, the CAQ formed a majority government and imposed Bill 21 on June 14 2019, which forbids teachers and many other state employees to wear religious symbols.

Still relying on its racist discourse, the PQ is nowadays the only opposition party that supports this law—regardless of the fact that their popularity is radically going down since they began to employ this approach. Now with only nine seats, making it the fourth party in importance, the PQ is on its deathbed. Instead of defending nationalism by working to build the country of Québec, it has aligned with far-right groups’ political narrative. For them, the State must defend the population against ethnic diversity and Islam. However, because of the many disguises the xenophobic movements have put on these discriminatory practices—invoking laicity, Québec values, and other ideological euphemisms—it took years for antifascist and antiracist groups to gain some legitimacy in the struggle against discriminatory law projects.

Instead, it was mostly moderate humanist groups that fought against these laws, leaving to the radicals the fight against overtly fascist organizations like Atalante Québec. These days, however, groups from a large spectrum of the left are allying to resist against Bill 21 and the Legault government. They are less and less afraid to point out mainstream right-wingers as racists. As the years go by, it is more and more difficult for ethnic nationalists to legitimate their movement since Quebecers have been fed their "we’re not racists, but… " rhetoric to a point it cannot ingest more without taking a stance toward either chauvinism or internationalism.

Québec’s situation is not bright with the CAQ in power and neo-fascist groups growing influence in the streets, but now there are counter-movements organizing. On June 19, Montreal activists proclaimed the beginning of a hunger strike to protest Bill 21. In Québec City, an anti-Bill 21 coalition was formed on the initiative of muslim women, students and other feminists. Against the media-fueled xenophobia put forward by the government, a small but significative spectrum of the population is now determined to pinpoint the fact that the nationalist movement in the province is no more a progressive-looking and liberty monger set of forces, but a proper conservative anti-immigration movement.

About the Creator

André-Philippe Doré

Student in Classics. Lives in Quebec City. Writes also (in french) for the socialist newspaper Offensive.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.