Early Cultures In America

"Old is always marking history".

Early Cultures in the America

Archaeologists have labeled the earliest humans in North America the Clovis peoples, named after a site in New Mexico where ancient hunters around 9500 B.C.E. (before the Common Era) killed tusked woolly mammoths using distinctive "Clovis" stone spearheads. They also used a wooden device called an atlatl, which gave them added leverage to hurl spears farther, and more accurately. Over many centuries, as the climate warmed, days grew hotter, and many of the largest mammals-mammoths, mastodons, giant bison, and single - hump camels-died, and grew extinct.

Skeletal remains of Paleo-Indians reveal that the women were much smaller than the men, who're bold, aggressive, and hypermasculine. More than half of the male skeleton show signs of injuries caused by violence. Four out of ten have fractured skulls. The physical evidence is clear: Paleo-Indian men assaulted, and killed each other with regularity.

Over time, the ancient Indians adapted to their diverse environments-coastal forests, grassy plains, southwestern deserts, eastern woodlands. Some continued to hunt large animals; others fished, and trapped small game. Some gathered wild plants and herbs, and collected acorns, and seeds; others farmed. Many did some of each.

Contrary to the romantic myth of early Indian civilizations living in perfect harmony with nature, and one another, they in fact often engaged in warfare, exploited the environment by burning large wooded areas to plant fields, and over hunted large animals. They also mastered the use of fire; improved technology such as spear points, basketry, and pottery; and developed their own nature-centered religions.

By about 5000 B.C.E, Native Americans has adapted to the warmer climate by transforming themselves into farming farming societies. Agriculture provided reliable, nutritious food, which accelerated population growth, adn enable a once nomadic (wandering) people to settle down in villages. Indigenous people became expert at growing the plants that would become the primary food crops of the entire hemisphere, chiefly maize (corns), beans, and squash, but also chili peppers, avocados, and pumpkins. Many of them also grew cotton. The annual cultivation of such crops enabled Indian societies to grow larger, and more complex, with their own distinctive social, economic, and political institutions.

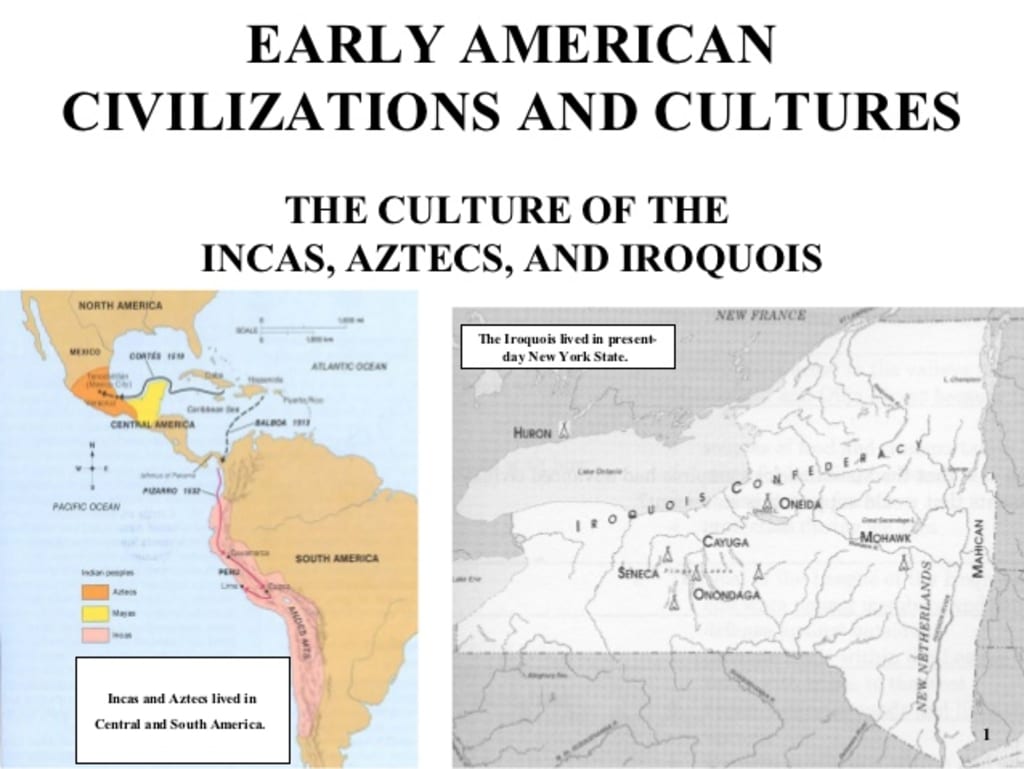

The Mayas, Incas, and the Mexica

Around 1500 B.C.E, farming towns first appeared in what is now Mexico. Agriculture supported the development of sophisticated communities complete with gigantic temple-topped pyramids, places, and bridge in Middle America (Mesoamerica, what's now Mexico, and Central America, where North, and South America meet). The Mayas, who dominated central America for more than the 600 years, developed a rich written language, and elaborate works of art. They also used sophisticated mathematics, and astronomy to create a yearly calendar more than the one the Europeans're using at the time of the Columbus.

The Incas

Much farther south, as many as 12 millions people speaking at least twenty different languages made up the sprawling Inca Empire. By the fifteenth century, the Incas' vast realm stretched some 2,500 miles along the Andes Mountains in the Western part of the South America. The mountainous Inca Empire featured irrigated farms, enduring stone buildings, and interconnected networks of roads made of stone.

The Mexica (Aztecs)

During the twelfth century, the Mexica(Me-SHEE-ka)-whom Europeans later called Aztecs ("People from Aztlan," the places they claimed as their original homeland)-began drifting southward from northwest Mexico. Disciplined, determined, and energetic, they eventually too control of the sweeping valley of Central Mexico, where they started building the city of Tenochtitlan in 1325 on an Island in Lake Tetzcoco, the site of present-day Mexico city. Tenochtitlan would become on of the largest city in the world.

Warfare was a sacred ritual for the Mexico, but it's a peculiar sort of fighting. The Mexico fought with wooden sword intended to wound rather than kill, since they wanted captives to sacrifice to the gods, and to work as slaves . Gradually, the Mexica conquered many of the neighboring societies, forcing them to pay tributes (taxes) in goods, and services developing a thriving trade in Gold, Silver, Copper, and Pearls as well as agricultural products. Towering stone temples, broad paves avenues, thriving marketplaces, and some 70,000 adobe huts dominated the dazzling capital city of the Tenochtitlan.

When the Spanish invaded Mexico in 1519, they found ta vast Aztec Empire connected by a network of roads serving 371 city-states organised into thirty-eight provinces. As their empire had expanded across central, and southern Mexico, the Aztecs had developed elaborate urban societies supported by detail legal systems; efficient new farming techniques, including irrigated fields, and engineering marvels; and a complicated political structure. Their arts're flourishing; their architecture's magnificent.

Aztec rulers're invaded with godlike qualities, and nobles, priests, and warrior-heroes dominated the social order. The emperor lived in the huge palace; the aristocracy lived in large stone dwellings, practiced polygamy (multiple wives), and were exempt from manual labor.

Like most agricultural peoples, the Mexica're intensely spiritual. Their religious beliefs focused on the interconnection between nature, and human life, and the sacredness of natural elements-the sun, moon, stars, rain, mountains, rivers, and animals. To please the gods, especially Huitzilopochtli, the Lord of the Sun, and brings good harvests, and victory in battle, the Mexica, like most mesoamericans, regularly offered live human sacrifices-captives, slaves, women, and children-by the thousands.

In elaborate weekly rituals, blood-stained priests used stone knives to cut out the beating hearts of sacrificial victims, and ceremonially offered them to the sun god to help his fight against the darkness of the night; without the blood from human hearts, he would be vanquished by the darkness. The heads of the victims're then displayed on a towering skull rack in the central plaza. The constant need for more human sacrifices fed the Mexica's relentless warfare against other indigenous groups. A Mexica song celebrated their warrior code: "Proud of itself is the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. Here no one fears to die in war. This's our glory."

North American Civilization

Many indigenous societies existed north of Mexico, in the present-day United States. They shared several basic spiritual myths, and social beliefs, including the sacredness of land, and animals (animism); the necessary of communal living; and the importance pf collective labor, communal food, and respect for elders. Native Americans did not worship a single god but believed in many "spirits." To the Sioux, the ruling spirit was Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit , who ruled over all the other spirits. The Navajo believed in the Holy People: Sky, Earth, Moon, Sun, Thunders, Winds, and Changing Woman.

Many societies believed in ghosts, the spirits of dead people who acted as bodyguards in battle. War dances the night before a battle invited the spirits to join the combat.

For all their similarities, the indigenous peoples of North America developed in different ways at different times, and in different places, often as strangers unaware of each other. In North America alone, there're probably 10 million native people organized into 240 different societies speaking many different languages when the Europeans first arrived in the early sixteenth century.

Native Americans owned land in common rather than separately, and they'd well-defined social roles. Men're hunters, warriors, and leaders. Women tended children, made clothes, blankets, jewelry, and pottery; dried animal skins, wove baskets, built, and packed tipis; and gathered, grew, and cooked food, Indians often lived together in extended family groups in a lodge, or tipi (a Sioux word meaning "dwelling"). The tipis're mobile homes made of buffalo skins. Their designs had a spiritual significance. The round floor represented the earth, the walls symbolized the sky, and the supporting poles served as pathway from the human to the spiritual world.

The Southwest

The dry Southwest (what is now Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah) hosted corn-growing societies, elements of which exist today, and heirs to which (the Hopis, Zunis, and others) still live in the multistory adobe (sunbaked mud) cliff-side villages (called pueblos by the Spanish) erected by their ancient ancestors. About 500 C.E. (Common Era), the native Hohokam ("those who've vanished") people migrated from Mexico northward to southern, and central Arizona, where they built hundreds of miles of irrigation canals to water crops. They also crafted decorative pottery, and turquoise jewelry, and constructed temple mounds (earthen pyramids used for sacred ceremonies). Perhaps because of prolonged drought, the Hohokam society disappeared during the fifteenth century.

The most widespread, and best known of the Southwest pueblo cultures're the Anasazi (Ancient Ones). They developed extensive settlements in the Four Corners region where the modern-day states of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah meet. Unlike the Aztecs, and Incas. Anasazi society's remarkable for not having a rigid class structure. The religious leaders, and warriors worked much as the rest of the people did. The Anasazi engaged in warfare only as a means of self-defense. (Hopi means "Peaceful People.") Environmental factors shaped Anasazi culture, and eventually caused its decline. Toward the end of the Thirteenth century, a lengthy drought, and the aggressiveness of Indian peoples migrating from the north led to the disappearance of Anasazi society.

The Northwest

Along the narrow coastal strip running up the heavily forested northwest Pacific coast, from northern California to Alaska, where shellfish, salmon, seals, whales, deer, and edible wild plants're abundant, there's little need for farming. In fact, many of the Pacific Northwest peoples, such as the Haida, Kwakiutl, and Nootka, needed to work only two days to provide enough food for a week. Because of plentiful food, and thriving trade networks, the Native Americans populations's larger, and more concentrated than in other regions.

Such social density enabled the Pacific coast peoples to develop intricate religious rituals, and sophisticated woodworking skills. They carved towering totem poles featuring decorative figures of animals, and other symbolic characters. For shelter, they built large, earthen-floored, cedar-plank houses up to 100 feet long, where whole groups of families lived together. They also created sturdy, oceangoing canoes carved out of red cedar tree trunks-some large enough to carry fifty people. Socially, the Indians bands along the northwest Pacific coast're divided into slaves, commoners, and chiefs. Warfare usually occurred as a means to acquire slaves.

The Great Plains

The many different peoples living on the Great Plains (Plains Indians), a vast, flat land of cold winters, an hot summer west of the Mississippi River, and in the Great Basin (present-day Utah, and the Nevada) included the Arapaho, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Apache, and Sioux. As nomadic hunter-gatherers, they tracked enormous herds of bison across a sea for grassland, collecting seeds, nuts, roots, and berries as they roamed. At the center of most hunter-gatherer religions is the animistic idea that the hunted animal is a willing sacrifice provided by the gods (spirits). To ensure a successful hunt, these nomadic peoples performed sacred rites of gratitude beforehand. Once a buffalo herd's spotted, the hunters would set fires to drive the stampeding animals over cliffs.

The Mississippians

East of the Great Plains, in the vast woodlands from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean, several "mound-building" cultures flourished as predominantly agricultural societies. Between 800 B.C.E and 400 C.E., the Adena, and later the Hopewell peoples (both names derive from the archaeological sites in Ohio) developed communities along rivers in the Ohio Valley. The Adena-Hopewell cultures focused on agriculture, growing corns, squash, beans, and sunflowers, as well as tobacco for smoking. They left behind enormous earthworks, and 200 elaborate burial mounds shaped like great snakes, birds, and other animals, several of which're nearly a quarter mile long. Artifacts buried in the mounds've revealed a complex social structure featuring a specialized division of labor, whereby different groups performed different tasks for the benefit of the society as a whole. Some're fisher folk; others're farmers, hunters, artists, cooks, and mothers.

Like the Adena, the Hopewell also developed an extensive trading network from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, exchanging exquisite carvings, metalwork, pearls, seashells, copper ornaments, and jewelry. By the sixth century, however, the Hopewell culture disappeared, giving way to a new phase of Native American development east of the Mississippi River, the Mississippian culture, which flourished from 800 to 1500 C.E.

The Mississippians , centered in the southern Mississippi Valley, were also mound-building, and corn-growing peoples led by chieftains. They grew corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers , and they built substantial towns around central plazas, and temples. The Mississippian peoples, the most powerful of which're the Natchez, developed a far-flung trading network that extended to the Rocky Mountains. Their ability to grow large amounts of corn each year in the fertile flood plains of rivers spurred rapid population growth around regional centers.

Cahokia

The largest of these advanced regional centers, called chiefdoms, was Cahokia (1050- 1250 C.E), in southwest Illinois, just a few miles across the Mississippi River from what's now St.Louis Missouri. There the Mississippians constructed an intricately planned farming settlement with monumental public buildings, spacious ceremonial plazas, and more than 100 flat-topped earthen pyramids with thatch-roofed temples on top.

Over the years, the Cahokians cut whole forests to create their huge village and to protect it with a two-mile-long stockade built of 15,000 oak, and hickory logs twenty-one feet tall. At the height of its influence, prosperous Cahokia hosted 15,000 people on some 3,200 acres. making it the largest city north of Mexico. Outlying towns, and farming settlements ranged up to the fifty miles in all directions.

Cahokia, however, vanished after 1250, and its people dispersed. What caused its collapse remains a mystery, but environmental changes're the most likely reason. The overcutting of trees may've set in motion ecological changes that doomed the community when a massive earthquake struck around 1200 C.E. The loss of trees led to widespread flooding, and the erosion of topsoil 1200 C.E. The loss of trees led to widespread flooding, and the erosion of topsoil that finally forced people to seek better lands. As Cahokia disappeared, however, its former residents carried with them its cultural traditions, and spread its advanced ways of life to other areas across the Midwest, and into what is now the American South.

Eastern Woodlands Peoples

After the collapse of Cahokia, the Eastern Woodlands peoples rose to dominance along the Atlantic seaboard from Maine to the Florida, and along the Gulf coast to the Louisiana. They included three regional groups distinguished by their different languages: the Algonquian, the Iroquoian, and the Muskogean. These're the societies the Europeans would first encounter when they arrived in the North America.

The Algonquians

The Algonquian speaking peoples stretched from the New England seaboard to lands along the Great Lakes, and into the Upper Midwest, and south to New Jersey, Virginia, and the Carolinas. They constructed no great mounds, or temple topped pyramids. Most Algonquians lived in small, round shelters called wigwams, or multifamily longhouses. Their villages typically ranged in size from 500 to 2,000 people, but they often moved their villages with the seasons.

The Algonquians along the Atlantic coast're skilled at the fishing, and gathering shellfish; the inland Algonquians excelled at hunting deer, mouse, elk, bears, bobcats, and mountain lions. They often traveled the regions's waterways using canoes made of hollowed.-out trees trunks (dugouts), or birch bark.

All of the Algonquins foraged for wild food (nuts, berries, and fruits), and practice agriculture to some extent, regularly burning dense forests to improve soil fertility, and provide grazing room for deer. To prepare their vegetable gardens, women broke up the ground with hoes tripped with clam shells, or the shoulder blades from deer. In the spring, they planted corn, beans, and squash in mounds. As the cornstalks rose, the tendrils from the climbing bean plants wrapped around them for support. Once the crops ripened, women made a nutritious mixed meal of succotash, combining corn, beans, and squash.

The Iroquoians

West, and south of the Algonquians're the powerful Iroquoian-speaking peoples (including the Seneca, Onondaga, Mohawk, Oneida, and Cayuga nations, as well as the Cherokee, and Tuscarora), whose lands spread from upstate New York southward through Pennsylvania, and into the uplands regions of the Carolina, and Georgia. The Iroquois're farmer/ hunters who lived together in extended family groups (clans), sharing bark-covered longhouses in towns of 3,000, or more people. The oldest woman in each longhouse's deemed the "clan mother" of the residents. Villages're surrounded by palisades, tall fences made of trees intended to fend all attackers. Their most important crops're corn, and squash, both of which figure prominently in Iroquois mythology.

Unlike the Algonquian culture, in which men're dominated, women held the key leadership roles in the Iroquoian culture. As an Iroquois elder explained. "In our society, women're the center of all things. Nature, we believe, has given women the ability to create; therefore it's only natural that women be in positions of power to protect this function.

Men, and women're not treated as equals. Rather, the Two genders operated in Two separate social domains. No woman could be a chief; no man could head a clan. Women selected the chiefs, controlled the distribution of property, and planted, and harvested the crops. After marriage, the man moved in with the wife's family. In part, the Iroquoian matriarchy reflected the frequent absence of Iroquois men, who as skilled hunters, and traders traveled extensively for long periods, requiring women to take charge of domestic life.

War between rival groups of Native Americans, especially the Algonquians, and Iroquois, was commonplace, usually as a means of settling feuds, or gaining slaves. Success in fighting's a warrior's highest honor. As a Cherokee explained in the eighteenth century, "We cannot live without war. Should we make peace with the Tuscaroras, we must immediately look out for some other nation with whom we can engage in our beloved occupation."

Eastern Woodlands Indians

The third major Native American group in the Eastern Woodlands included the southern peoples along the Gulf coast who spoke the Muskogean language; the Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws. Like the Iroquois, they're often matrilineal societies, meaning that ancestry's traced only through the mother's line. but they'd a more rigid class structure. The Muskogeans lived in towns arranged around a central plaza. In the region along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, many of their thatch roofed houses had no walls because of the hot, humid summers.

Over thousands of years, the native North Americans'd displayed remarkable resilience, adapting to the uncertainties of frequent warfare, changing climate, and varying environments . They would display similar resilience in the face of the challenges created by the arrival of Europeans.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.