Can Social Enterprises Empower Urban Refugees?

A West Java Case Study

As intrastate conflicts throughout the world continue to outbreak and fester, a huge humanitarian crisis has emerged on a global scale. In 2018, nearly 69 million people in the world have been forcibly displaced from war, violence or persecution. Of this figure, 40 million people are internally displaced, 25.4 million are refugees and 3.1 million are asylum-seekers.

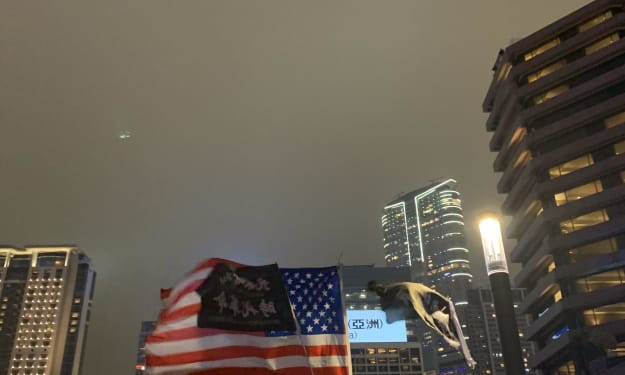

For Indonesia, it was initially used as a transit country for refugees to resettle into other states, particularly Australia. However, tough immigration policies enforced by conservative Australian government have put these communities in limbo of a future. Since 2016, Indonesia hosts approximately 13,829 refugees and asylum seekers coming from predominantly Afghanistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Iran and more. This potentially rising number in refugees presents a unique challenge for Indonesia; the nation has slowly moved away from a transiting country to potentially a country of resettlement for these communities, creating the urban refugee.

An urban refugee is an individual who seeks protection from their own state within the urban settings on another country with many residing in these areas in hopes of economic prosperity and opportunity. Many urban refugees have escaped their own countries to states that are over-populated, have inadequate infrastructure and stretched public services which is the case for many refugees in Indonesia. The pursuit of urban settings for refugees gives them greater economic opportunities but they face many risks including discrimination, unemployment, lack of housing, limited healthcare and violence. The neighbourhoods that urban refugees reside in have higher levels of crime, unemployment, poor shelter and limited basic services.

‘Unlike a camp, cities allow refugees to live autonomously, make money and build a better future’ (UNHCR 2019).

The 1951 Refugee Convention sets out the legal framework for refugee rights and protections under a particular state. As Indonesia is not a party to this Convention, the country is not obliged to integrate refugees into the country and leaves them with an inability to work. Indonesia is also not dependent on migrant workers to fill the labour market, often creating a stigmatisation against hiring foreigners.

One of the biggest challenges for Indonesian urban refugees is the access to financial capital in order to become self-reliant and independent from foreign aid. Many urban refugees are heavily dependent on donations from family members abroad and humanitarian aid for economic stability. For many, the survival is day-to-day; unassisted refugees cannot be considered self-reliant when subject to poverty, if they are obliged to engage in illicit activities to survive or are dependent on remittance.

In West Java, the Cisarua community holds approximately 6,000 asylum seekers and refugees. The ‘transit refugee’ status has made these communities reluctant to fully settle and integration within the local Indonesian community despite many not resettling for more than 10 years. In Cisarua, the communities here have limited uptake of the language and cultural practices in Indonesia, with little evidence of integration. The lack of services and economic opportunities provided by the government gives rise to an opportunity to invest in social enterprise for community empowerment.

Social enterprise takes business-like, innovative approaches to deliver public services and invest in resilience of marginalised communities, making emphasis on innovation in all social value creating activities. In a country like Indonesia where state services are lacking to help refugees, social enterprises flourish in promoting a culture of self-reliance and entrepreneurship. Social enterprise aims to move away from grants and charities of non-for-profit organisations and instead use the value of local community orientation to be participants and consumers of a business. The values engrained in this business model are not profit gaining but rather social capital building by increasing community participation, social inclusion.

Refugees bring a range of skills, knowledge and innovative work and business practices, enhanced by resilience that is carved by their journey from fleeing their home countries. This business model helps enhance employability, entrepreneurial skills, leading to self-reliance, self-esteem, and reduce stigmatisation and build social capital. It reinforces positive psychological effects of belonging, hope, wellbeing and happiness and can help bridge a gap between host communities and refugee communities.

The Cisarua community also has a social enterprise called Beyond the Fabric which empowers women to support their families by providing education and skills. Supported by the Refugee Women Support Group Indonesia, this group focuses on textile and jewellery making, whilst also running workshops on women’s issues like health, hygiene, reproductive health, sexual and gender-based violence and family planning. This initiative teaches women handicraft that is then used to make garments and bags. These garments are distributed in Jakarta and Australia to be sold, with all profits returned to the women to spend on what they need. Donations can further be made by purchasing new sewing machines for these women, as well as buying products.

Social enterprise in Indonesia has become a space for refugee communities to create social networks, playing a significant role in job security and accessing opportunity. Without local, indigenous networks, refugees will remain on the fringes of the labour markets. Social capital built through social enterprise not only enhance refugee protection, but provides information dissemination about NGO services, other employment opportunities and housing.

Economic opportunities through social enterprise can not only help refugees restore their dignity but allow them to support local economic development and improve government health and education. When refugees are self-reliant, humanitarian assistance can be used to rehabilitate local roads, schools, health clinics to benefit refugee and host communities. Issues of economic competitiveness are set aside to empower both local and refugee communities.

References

Ali, M, Briskman L & Fiske, L 2016, ‘Asylum seekers and refugees in Indonesia: Problems and potentials’, Cosmopolitan Civil Societies Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 22-43.

Argandona, A 1998, ‘The stakeholder theory and the common good’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 17, no. 10, pp. 1093-1102.

A Tol, W, Luitel, N.P, Roberts, B, Thomas, F.C & Upadhaya, N 2011, ‘Resilience of refugees displaced in the developing world: a qualitative analysis of strengths and struggles of urban refugees in Nepal’, Conflict and Health, vol. 5, no. 20, pp. 1-11.

Barraket, J 2007, ‘Pathways to employment for migrants and refugees? The case of social enterprise’, The Australian Sociological Association, pp. 1-8.

Brown, T 2017, ‘After the boats stopped: Refugees managing a life of protracted limbo in Indonesia’, Antropologi Indonesia, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 34- 50.

Brown, T.M. 2018, ‘Building resilience: The emergence of refugee-led education initiatives in Indonesia to address service faced in protracted transit’, Australian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 165-181.

Buscher, D 2011, ‘New approaches to urban refugee livelihoods’, Refuge, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 17-29.

Bull, M 2008, ‘Challenging tensions: critical, theoretical and empirical perspectives on social enterprise’, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 268-275.

Kong, E 2011, ‘Building social and community cohesion: The role of social enterprises in facilitating settlement experiences for immigrants from Non-English speaking backgrounds’, The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 115- 128.

Kong, E 2018, ‘Harnessing and advancing knowledge in social enterprise: Theoretical and operational challenges in the refugee settlement experience’, Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, pp. 1-18.

Luk, T & Xiang, R 2001, ‘Friends or foes? Social enterprise and women organising in migrant communities in China’ China Journal of Social Work, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 255-270.

Missbach, A & Palmer, W 2018, ‘Enforcing labour rights of irregular migrants in Indonesia’, Third World Quarterly, p. 1-18.

Rothschild, J 2009, ‘Worker’s cooperatives and social enterprise: A forgotten route to social equity and democracy’, American Behavioural Scientist, vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 1023-1041.

About the Creator

row / shell

Finding solace in writing. Heart on my sleeve.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.