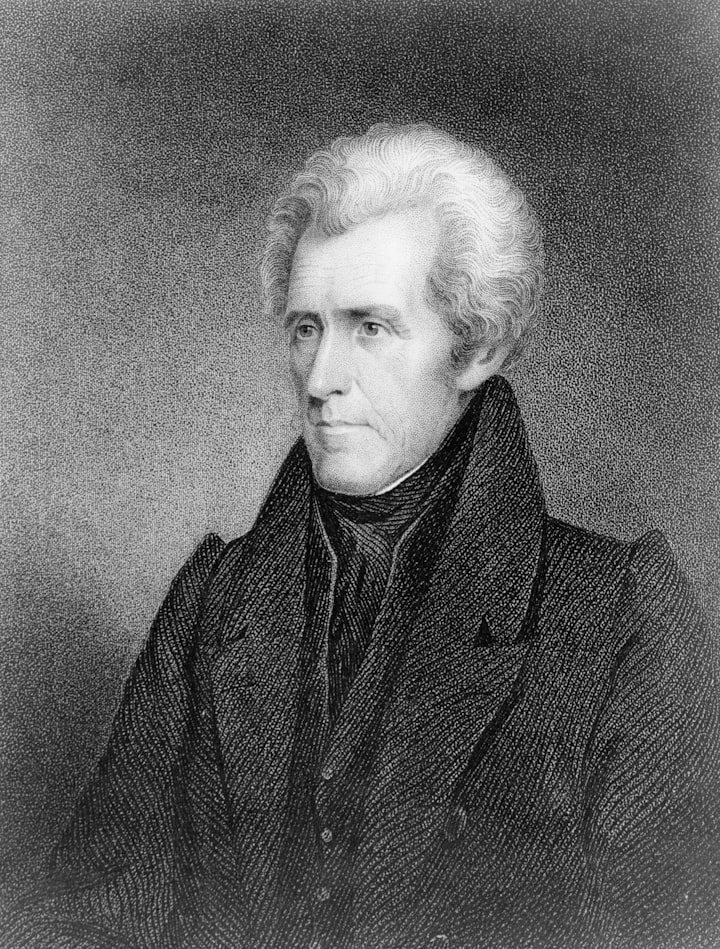

Andrew Jackson's Native Removal Policy

Was his policy motivated by humanitarian impulses?

As the seventh President of the infantile United States of America, Mr. Andrew Jackson assumed an office which not only granted him immense power, but also a glaringly cacophonic environment in which opposing factions would do seemingly anything to bring the other side down. Of the many divisive political issues present in 1828, none was perhaps of more importance - or in need of urgent debate - than the territories of Native Americans and where they fit in between the industrious North, the aristocratic and bountiful Southern coast and the agriculture-oriented, ever-expanding Western frontier. The general consensus of most white Americans was: not in our state. Regardless of motivation, a majority of the populous agreed that resettlement of Native Americans was necessary, and the best place to send them was West of the Mississippi River. As “the people’s president,” Jackson was inherently inclined to bend to the will of the people. Despite his rhetoric, which on the surface seemed compassionate and protective of the indigenous peoples, Jackson’s motivations were political, cultural, and economic, not humanitarian.

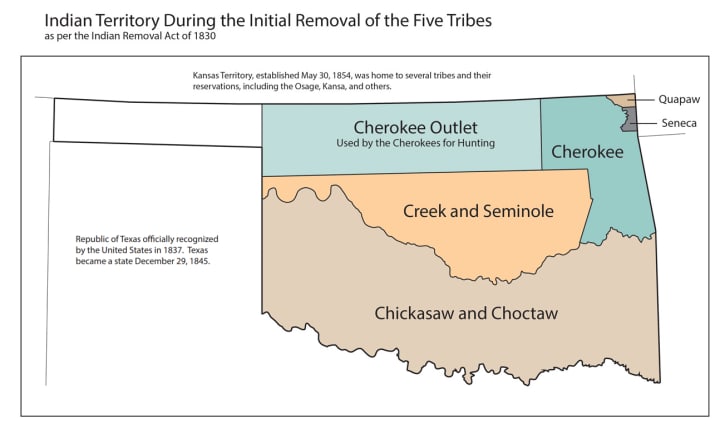

In both private conversations and public statements, Andrew Jackson was openly nationalistic, and subsequently pro-resettlement; Jackson “[rejected] any notion that jeopardized the safety of the United States,” including the sovereignty of Indian nations within the U.S. (1) A physical presence of natives within the country but a cultural and economical absence went against the foundation of Jackson’s political principles. Another portion of the political agenda spoke to the state of Georgia. The people and government of Georgia were vehemently opposed to Cherokee Indians remaining within their boundaries; in response to the Cherokee’s Constitution essentially making their territory a “state within a state,” and nullifying Georgia law, in December of 1828 Georgia’s legislative body extended their state’s jurisdiction over the Cherokees residing within their state. (2) The prosperity of an independent native people was not immensely beneficial to the white man, therefore it had to be prevented. The passing of this law and the ensuing strained relations between Indians and whites in Georgia placed immense pressure on Jackson to enact some form of Indian removal policy. After the President delivered a speech to Congress urging them to pass Indian removal legislation, intense debate ensued and eventually - in May of 1830 - a Removal Act was passed and immediately signed into law by Jackson. (3) Thus, another one of Jackson’s political motives for the removal of Native Americans had been satisfied.

If there was any doubt remaining in regard to the politicization of Indian removal by Jackson, one need only analyze a seemingly trivial action in regard to Jackson’s removal team. When the Superintendent of the Indian Office, Thomas McKenney, who was an ardent supporter of removal began exhibiting disapproval of the “harassment tactics of the administration,” he was promptly removed from office and replaced. (4) It appeared as though anything impeding the execution of Jackson’s political agenda, friend or foe, was quickly disposed of.

Political pressure was not the only driving force behind the swift enactment of removal policies. The general feeling of white Americans - mainly Southerners - was that American Indians were a savage people, incapable of becoming civilized and therefore compatible with traditional American culture. (5) This was not a new sentiment; it has been well-documented that ever since Europeans stepped foot on American soil there was constant struggle between the cultures and beliefs of the natives and the Old World. In the beginning, “colonists drove the Indians from their midst, stole their lands and, when necessary, murdered them.” (6) At the time just prior to the enactment of removal policies, high-ranking government officials shared openly racist ideas; Henry Clay stated that Indians were “inferior to white men and ‘their disappearance from the human family would be no great loss to the world.’” (7) Clearly, the removal of Indians from their tribal lands was influenced by the prejudiced views held by Americans and the centuries of hostile clashes between the two vastly contrasting cultures.

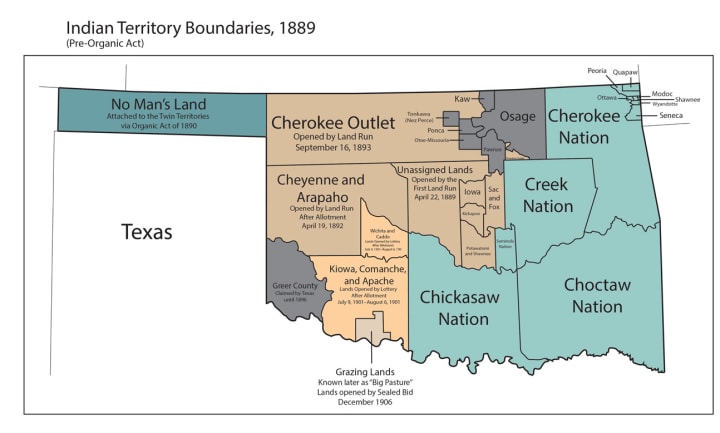

In keeping with the American tradition of economic domination, the resettlement of Indians was also designed to benefit the federal government financially. The entrenchment of Indians in the East severely threatened Americans’ goal of Manifest Destiny; if the Americans did not have possession of or access to the land on which Indians resided, then there was no way they could make a profit off of or benefit from said real estate. Prior to removal being passed by Congress and executed by the President, the Indians’ lands were already being parceled out; once the legislation was signed into law, it was full steam ahead. Most of the land that was ceded became public land owned by the Federal government which it then auctioned off. The remaining land was doled out through private sales. “The Jackson administration was ready to do its ‘land-office business’ as soon as the Indians could be persuaded to sell and agree to move...efforts to that end were already under way.” (8) The blatant assumption that Indians would cede land and the Federal government would subsequently be able to profit, even if meagerly, was anything but humanitarian.

The idea that Jackson’s removal policies were more politically, culturally, and economically motivated is not to say that there were no humanitarian undertones whatsoever. Jackson well understood the sentiments of his people and “believed that removal was indeed the only policy available if the Indians were to be protected from certain annihilation." (9) As has been discussed, the superior firepower as well as combat experience of the whites had been detrimental to the natives during colonization. Although times had changed and Indians had obtained weapons of the white-man, the economic and military might of the United States still dwarfed that of the natives. Another example of slight humanitarian undertones, perhaps with more than a pinch of political motivation, can be seen in the removal of the Choctaw Nation. Under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, the Choctaws were to leave their territory and migrate to an area in what is now Oklahoma; since this was one of the earlier instances of removal, Jackson wanted “everything to go smoothly so that the American people would understand that removal was humane and beneficial to both the Indians and the American nation at large.” (10) It could be inferred that Jackson wanted to ensure his popularity and political power by making sure all sides were satisfied with his removal policies; therefore he tread with light-feet and a white-glove type of policy. When the removal did not go as planned - it was filled by strife, suffering, abuse, and corruption - Jackson was most certainly displeased. When he found out the manner in which the removal of the Choctaws was conducted, “[he] was deeply offended” and imposed new guidelines for removal to prevent similar situations happening in the future. (11) So although there were dishonest and covert tactics used, the Indian removal policies were not one-hundred percent persecutory.

To look at Andrew Jackson’s Indian removal policies as a black and white issue is a grave offense to history. The country was changing rapidly and, not only was legislature struggling to keep up, but so too were the minds and hearts of the American people. Jackson had a lot on his plate, so to speak, and had to please factions which had radically different views. He also had to ensure he did what was best for his nation, a cause near and dear to his heart. Therefore, despite his sympathetic and politically correct public rhetoric, the motivations behind his policies were anything but humanitarian; the President was determined to ensure that the removal of Native Americans would have positive political, cultural and economic implications for both himself and his constituents.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.