A Lesson from Buffalo Bill, Pawnee Bill and the New York Suffragists

Time to rethink today’s love affair with tribalism

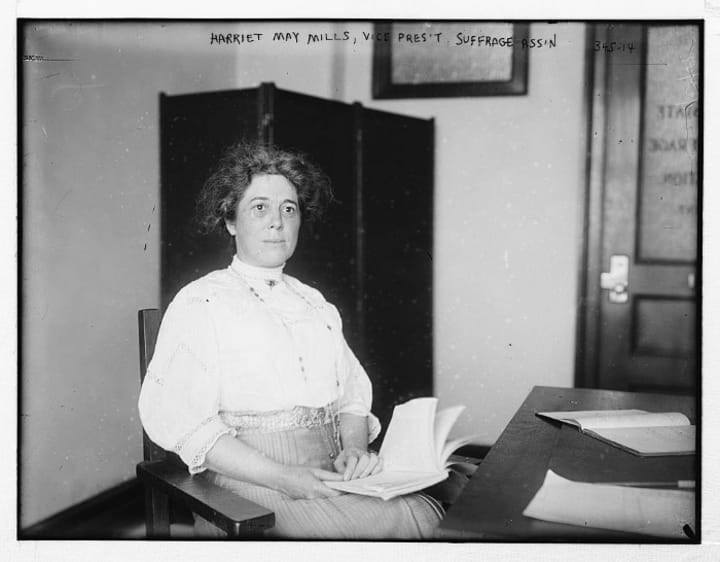

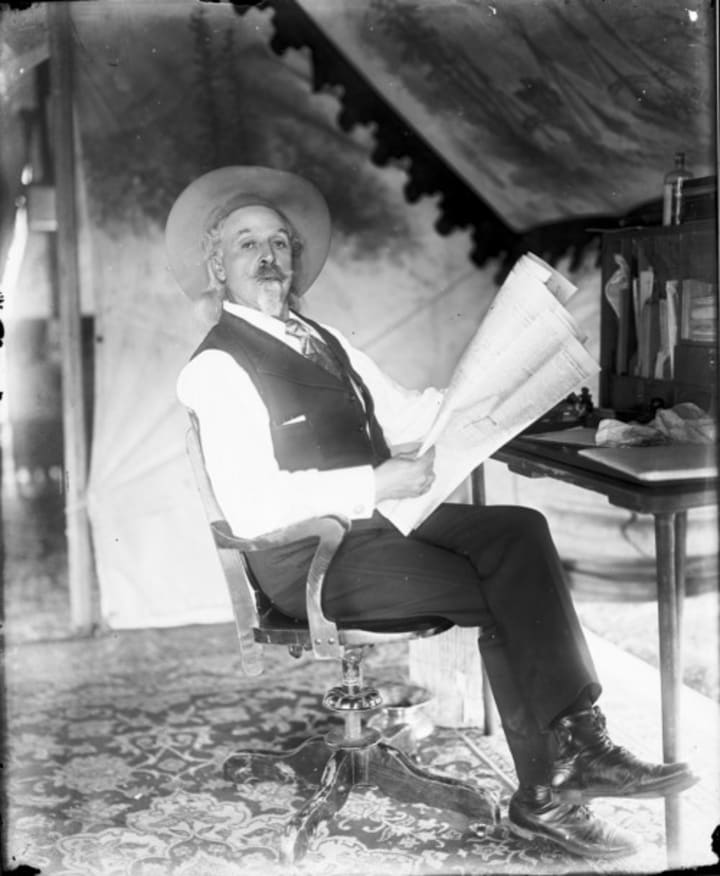

Skirts aswirl, fourteen New York suffragists strode through Madison Square Garden. Among them were prominent society members such as the Misses Portia Willis, Harriet May Mills, Gertrude Lee, and Helen Benson. These were women far more familiar with Victorian silver choices than life in the open air. Entering the mess hall that April evening in 1913, they spied their quarry in the corner and beetled over. The two white-haired men were hunkered down over a meal of roast beef, corned beef and cabbage, lima beans, potatoes, and rice pudding. Maybe a little heavy on the starch, but Colonel Cody and Major Lillie had survived on much worse. And they couldn’t be too picky now either. Edison’s moving picture shows had eaten into the Wild West business. Old pals Cody and Lillie had thrown in together to create the “Buffalo Bill Wild West and Pawnee Bill Far East” Show. By autumn they’d be bankrupt, but for tonight they were still in the game.

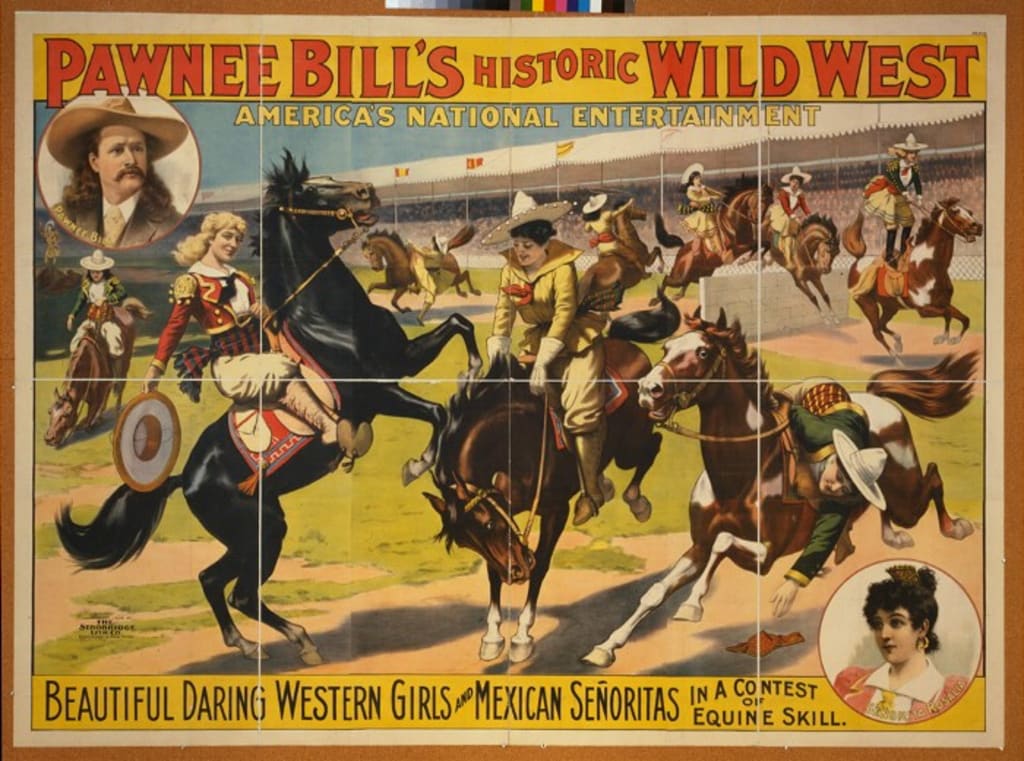

Mrs. Marie Nelson Lee, President of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association and experienced in the ways of negotiation, led with a soft pitch. Buffalo Bill had avowed support for women’s suffrage as early as 1894 and Mrs. Lee had already talked at least once with him about her upcoming project. She would be riding a prairie schooner through upstate New York in a quest for converts to her cause. She thought Pawnee Bill might have some good tips on how to rough it, how to make coffee on the trail, and such things. Eventually the conversation turned to other ways the men might help the women’s cause.

An enormous suffrage parade was planned for the coming Saturday in Manhattan. Mrs. Lee had hoped to ride the prairie schooner in the parade, but it wasn’t ready. The men agreed to loan the women a schooner from the Wild West show. The suffragists pressed their luck. By the end of the conversation, five Wild West cowgirls had volunteered to ride in the suffrage parade.

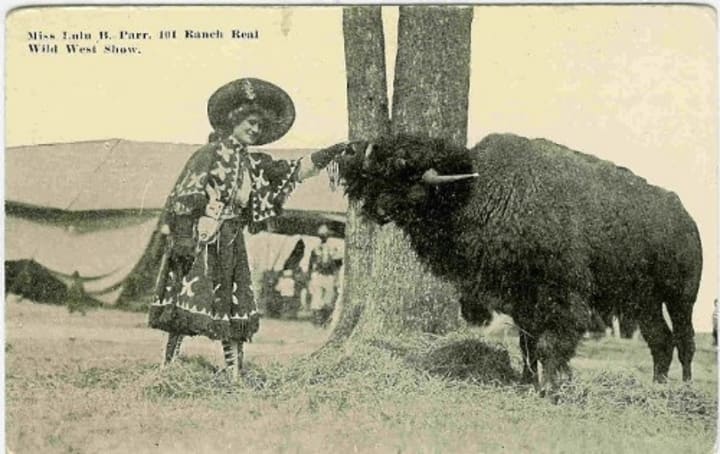

Of the five cowgirl volunteers, Lulu Bell Parr’s achievements are the best known. A sharp shooter, buffalo and bronco rider, and all-around excellent equestrian, she also sewed her fancy beaded and spangled costumes herself. Deemed “Champion Lady Bucking Horse Rider of the World,” she performed internationally over the years with all the major Wild West shows. Joining her in the parade would be sisters May and Margaret Griffith, Helen Saunders, and Lillian Compton.

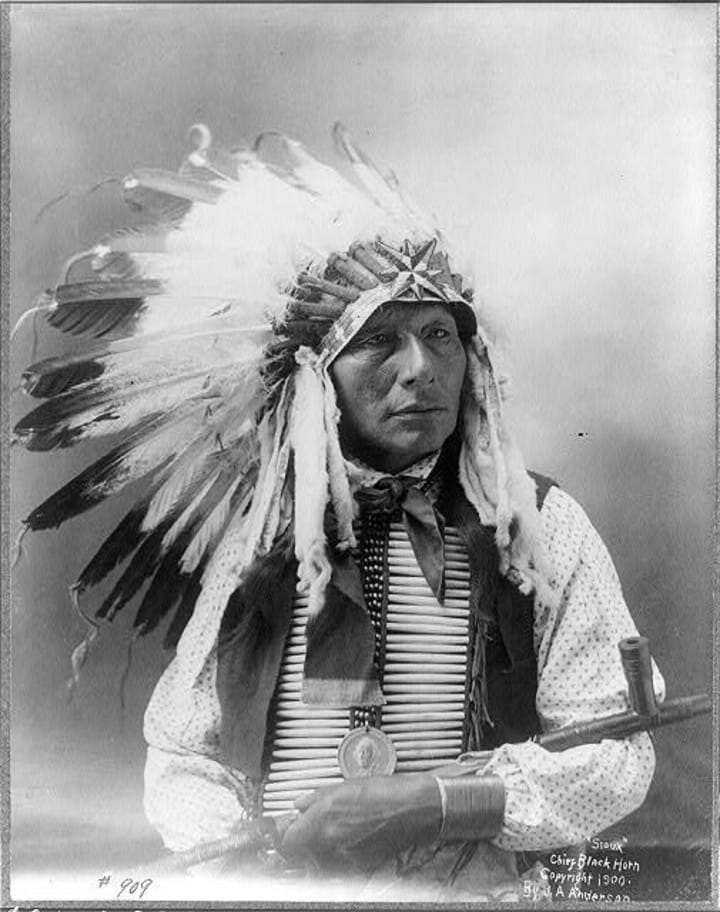

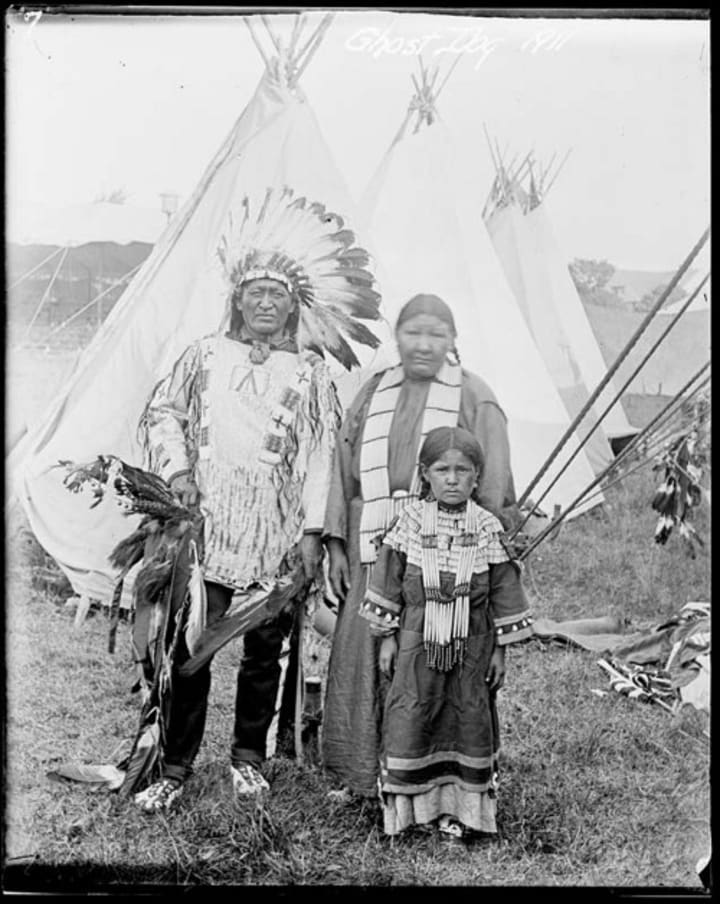

Cowboy performers had stepped up to help and been refused by the two Bills. Instead, five Native American men’s offer to ride in the parade as guardians for the cowgirls was accepted. This was not necessarily a ceremonial role. Two months earlier male onlookers had mobbed and spat upon women in the Washington, DC suffrage parade. Guarding the cowgirls would be Daniel Black Horn, Red Feather, Acey Ghost Dog, Sitting Eagle, and Albert Kills-in-Winter. Trusted employees, all had done work for Cody since the 1890s. Daniel Black Horn, a Lakota, had served as chief of the show’s Native American village which included Apaches, Pueblos, Navajos, and members of other tribal groups.

That evening, the Native Americans and cowgirls left the mess hall to work on their “Votes for Women” yells. The women planned a cowgirl yell and the men worked on translating the slogan into their language.

On Saturday, May 3, lawyer Iris Milholland mounted a frisky chestnut colt and led thirty thousand women and two thousand men up Fifth Avenue. Forty bands played while 250,000 bystanders watched the procession. Society stars, news boys, social workers, babes in arms, Vassar students, actresses, and opera singers all marched including — the papers noted — “Indians, cow girls and a prairie schooner.

Later that month, Lulu Bell Parr declared in a newspaper interview, “I am a suffragette in every sense of the word…I am proud to be a suffragette.” If she hadn’t been a suffragist before the march, she was one now. In 1920, the suffragists’ goal would come to fruition.

A crazy quilt of supporters had helped birth the dream including the two Bills, the cowgirls, and the five Native Americans. Sitting Eagle had stretched himself from his days as an Oglala warrior at the Battle of the Little Big Horn to become a participant in a suffrage parade. The five guardians of the cowgirls, on the face of it, had little to gain from “Votes for Women.” Indigenous people would not be granted American citizenship until 1924. Voting rights for Native Americans would not be guaranteed in every state until the 1960s and even that progress has been nibbled at in this century.

Indigenous men like Red Feather lacked the freedom to go where they wished or do as other men did. Government agents permitted only “Indians of good moral character” to leave the reservation for work. Cash bonds assured their return. In 1894, Cody posted a forty-thousand-dollar bond to hire a contingent of one hundred South Dakota Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapahos for his Long Island Wild West show.

Ghost Dog’s contract for the show was explicit: he would be paid twenty-five dollars a month of which forty percent would be withheld until he returned to the reservation. He would be fined twenty-five dollars (or dismissed and lose all his money) if he became drunk.

Yet within the constraints of their life, these men had the generosity and gumption to support a woman’s right to vote.

The New York suffragists intentionally sought diverse participation to gain their goal. Contrast that stratagem with today’s approaches. Folks are busy finding their tribes rather than leading across tribal edges as Daniel Black Horn did. Terms such as “cultural appropriation” and “communities” draw bright lines separating groups rather than identifying their unifying goals. This fragmentation risks dysfunction, dispiritedness, and discombobulation.

Let’s take a lesson from the past and work beyond tribalism toward common aims. These overarching goals may not directly benefit each of us but are good for society as a whole. Let’s do better. Let’s pull together.

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.