The story of the ‘queen of flowers’

The rose has been associated with everything from debauchery to purity.

“It might well be said of this beautiful flower, that nature has exhausted herself in trying to lavish on it the freshness of beauty, of form, perfume, brilliancy, and grace.” This is how Charlotte de la Tour describes the rose in her famous book Le Langage des Fleurs (The Language of Flowers). In it, the rose occupies a central and almost hallowed position. Her sentiments were nothing new; before the publication of her book in 1819, the rose had – for millennia – been prized for its beauty, both aesthetic and olfactory. Like de La Tour, the Greek writer Achilles Tatius called the rose the “queen of flowers” in the second century AD, and to Persian poets like Hafez, its loveliness was unrivalled. And the rose continues to be strongly associated with beauty today, as it does with love; but within its folds lie many other connotations, some of which aren’t as rosy. Ravishing: The Rose in Fashion, an upcoming spring 2021 exhibition at the Museum at FIT (New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology), explores the myriad meanings of what is perhaps the most symbolically rich – and controversial – flower, not only in fashion but in everything from mythology and literature to religion and politics.

Although it has been suggested that the rose was first cultivated in China some 5,000 years ago, the flower is in fact far older. “The genus rosa dates back 35 to 40 million years,” says Amy de la Haye, a co-curator of the MFIT exhibition, “so the rose goes right, right back”. In the Near East, according to historian Mauro Ambrosoli, the popularity of the rose spread along with the Persian idea of the paradise garden, and, as says Anna Pavord, editor of the forthcoming book Flower: The World in Bloom, it made its way to Europe via the Romans. “It was brought in by merchants,” she tells BBC Culture. “The Romans imported plants from the East.”

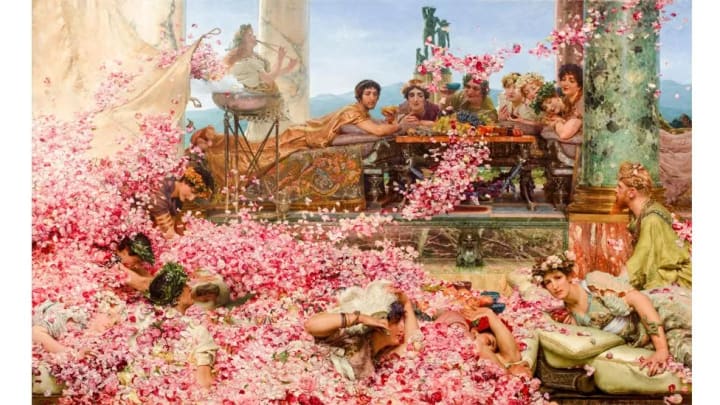

The Romans didn’t import the rose simply to gaze at in their gardens, though; they exploited the flower to its fullest. Mairi Mackenzie writes in the show’s accompanying book that rose perfume and water were used by people of varying social classes – as scents, in food and wine, and for bathing purposes. And, far before Jagger and Richards promised little Susie to put roses on her grave, the Romans, Pavord says, used roses “in garlands to honour the tombs and spirits of the dead”. Then there were the petals. It was customary, for example, to use them as carpets on special occasions, but sometimes things got out of hand. In his 1888 painting The Roses of Heliogabalus, Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicts a feast at which some of the emperor’s guests are being drowned – literally – in a shower of rose petals. While the incident’s authenticity has been doubted, it isn’t too implausible. Jonathan Faiers, a professor at the UK’s Winchester School of Art, describes Heliogabalus as “juvenile and hedonistic”; and, as Richard Webster notes in his book Magical Symbols of Love and Romance, the emperor Nero reportedly spent four million sesterces (ancient Roman coins) on petals for a single banquet. “It’s a commentary on, sort of, the decadence of the period,” de la Haye tells BBC Culture.

Over time, the rose’s associations with love, femininity, purity and death were further developed

This is all, of course, not mentioning the Rosalia, the extravagant rose festival held annually in Rome; and the link with decadence also extended into Roman religion. It was believed that Cupid gave a rose to Harpocrates – an Egyptian god who to the Greeks and Romans symbolised silence – in exchange to keep the amorous affairs of his mother, Venus, secret; hence the Latin term sub rosa (literally ‘under the rose’), which is still used today to request silence regarding matters discussed in private.

It was because of such associations that Christianity was initially opposed to the use of the rose as a symbol for the Virgin Mary. “The early Church fathers,” Richard Webster explains, “loathed the rose, because they associated it with the lust and debauchery they saw in the Roman Empire”. Ultimately, however, the rose prevailed, and was declared “the most perfect of flowers,” according to Teresa McLean in her book Medieval English Gardens, “one which had been without thorns when it grew in Paradise, until the disobedience of Adam and Eve…” Consequently, Mary came to be represented by a white and thornless rose. Nicholas Hilliard’s famous ‘Pelican’ portrait of Elizabeth I (c 1573-75), in which the queen appears beneath a thornless rose, illustrates the rose’s newfound Christian associations with chastity.

That said, some pagan links persisted in the new religion. According to the Greek writer Pausanias, the rose obtained its red colour from the blood of Aphrodite (Venus), who cut her feet on the thorns of a rosebush while rushing to her dying lover, Adonis. These ties to blood and death were later incorporated in the rose as a symbol for Christ. “[Christ’s] five bleeding wounds,” writes McLean, “were the five petals of the red rose, his crown of thorns the thorns of the rose bush”.

Over time, the rose’s associations with love, femininity, purity and death were further developed in literature and art, as well as botany. In the 13th Century Le Roman de la Rose (The Romance of the Rose), a tale “replete with puns centred on rosy de-flowerings, pricking, scattering seed, and seizing young buds,” Faiers says, “the rose is both the object of the narrator’s desire and a symbol for female sexuality”. The term ‘deflower’, however, first appeared in A Directory for Midwives, a book by the 17th-Century English botanist Nicholas Culpeper, who, writes De La Haye, “[likened] the fleshy knobs around the hymen to a half-blown rose”. Such comparisons, including those made by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (regarding flowers in general) in the 18th Century, eventually led to the rose being once again the object of scorn – this time, in Victorian England. “It was reviled by people who were offended by its references to sexuality,” de la Haye says.

On a more sombre note, Shakespeare, in his 35th sonnet, commented on the ephemerality and fleeting beauty of the delicate rose: “And loathsome canker lives in the sweetest bud,” he wrote. This subject also served as the inspiration for William Blake’s poem The Sick Rose. Similarly, during World War One, roses – like the lone rose blooming in the barren landscape of René Magritte’s 1945 painting l’Utopie (Utopia)– became “emblematic of the beauty and fragility of life”, according to de la Haye, and were picked and dried in memory of the dead, and enclosed in letters.

New connotations also evolved around the rose, most notably in politics. In 15th-Century England, the houses of York and Lancaster fought for control of the throne in the Wars of the Roses. When the first Tudor monarch, Henry VII, defeated Richard III and married Elizabeth of York, he created the Tudor Rose out of the red rose of Lancaster and the white rose of York. “The contrast of the military might with the delicate rose proved irresistible,” writes Faiers of the Tudor Rose, which is now a national symbol of England. As well, because of its colour, the red rose has become linked with communism and socialism, and is the symbol of Britain’s Labour Party.

The rose in fashion

In spite of its reputation and appearances in the spheres of literature, art, and politics in Europe, it wasn’t until the 18th Century that roses, especially in England and France, began to be cultivated in earnest. The introduction of the China rose into Europe in the middle of the century sparked a fascination for all things rosy, and clothes were no exception. “By the end of the 18th Century,” writes scholar François Joyaux in Ravishing, “the rose was not only in minds and gardens: it was everywhere, in home decor, the ornamentation of furniture, [and] the adornment of women”.

As in ancient Egypt, both fresh and artificial roses were worn in Europe from the 18th Century onwards, but rose motifs also found their way on to silks and other fabrics. The flower, says Colleen Hill, another curator of the MFIT exhibition, lent itself particularly well in this regard. “One of the things that makes the rose such an exceptional motif in fashion is its ability to be rendered in myriad ways. The rose can be ‘sculpted’ from fabric, printed, woven, or painted. It can be abstracted and still recognised as a rose.”

To me, the rose signifies pure love and natural beauty – Richard Quinn

There are also its many associations, which have long been appreciated by many of the world’s great designers. An evening gown that the artist Jean Cocteau designed for Elsa Schiaparelli in 1937, for example, on whose back two figures appear kissing one another beneath a vase of roses, uses the flower as a symbol of love and romance. More recently, Prada used the rose in its 2019 Anatomy of Romance collection. On a similar note, the silk-rose skull caps of Christian Dior, who, in his own words, designed for “flower-like women”, and a young woman’s evening dress with an artificial pink rose protruding at the navel, designed around 1960 by Yves Saint-Laurent, recall the flower’s feminine connotations in Le Roman de la Rose.

On the other hand, designers including Dries Van Noten have explored the rose’s associations with death, decay, and the transience of life. The anthophile’s autumn/winter 2019/20 collection is a case in point, Van Noten tells BBC Culture: “There were a lot of really strange things happening in the world, so I thought it would be nice to [print] roses… but not perfect roses, to show also the realness of life.” The visual inspiration for the collection came from Van Noten’s garden. “[There were] roses with diseases, sometimes eaten by insects, [roses] scratched and damaged by rain and hail…” In Comme des Garçons’ 2015 Roses and Blood collection, Rei Kawakubo also examined the rose’s darker links. Presented on the centenary of World War One, it recalled the custom of picking roses by soldiers amidst the wreckage of the war.

The rose as a symbol of purity in fashion can perhaps best be seen in the use of white roses in wedding gowns. Richard Quinn looks at the rose from this perspective, too, although he doesn’t limit himself to white in his vibrant floral prints. “To me, the rose signifies pure love and natural beauty,” says the designer, who at the same time is “intrigued by how the rose’s “purity … can be subverted” through the use of materials like latex.

As for the political and patriotic connotations of the rose, heritage brand Kent & Curwen has been playing with them in an English context. “There’s definitely a pride in wearing that sort of crest on your chest,” says creative director Daniel Kearns of the rose – “a great English symbol” – which, for the past five-odd years has been emblazoned in Lancaster red on many of the brand’s outfits. Kearns, however, also appreciates the flower’s other meanings, and feels it far transcends its regal (and religious) roots in England. “It’s become itself a kind of iconography that stands alone,” he tells BBC Culture. “It’s associated with love, it’s associated with nature, with art, with all kinds of things, and I think in that way it creates a kind of broader subject.”

While designers have been drawing on the symbolism of the rose for centuries, and, as de la Haye says, “[especially] in the last 10 to 15 years,” Hill, like Van Noten, admits that most consumers don’t think about what it connotes. “Most people appreciate roses for their beauty above all else,” she says. Faiers also emphasises that this beauty is not only superficial, but also – and more importantly – transformative; and it is this transformative beauty that is at the heart of the exhibition. “The simple addition of a rose worn in a buttonhole [or] added to a corsage,” as Faiers points out, “can turn the wearers into princes and princesses”.

When the poet Gertrude Stein famously declared, “A rose is a rose is a rose” she may, says de la Haye, have been demanding “to see the rose for what it was… stripped of mythology and symbolism”. If so, this was a tall, if not altogether impossible order; for, while it may have been just a rose when it first sprang from the earth around 40 million years ago, it has – at least for millennia – evidently been anything but.

About the Creator

Many A-Sun

Where your interests lie, that's where your abilities lie.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.