I remember it as clearly as I remember my wedding day, the day my daughter was born, and the day my son was born. Those are joy-filled, major life events you simply cannot forget.

Tragedies strike everyone, in one form or another, at some point during their lifetime. It could be from the passing of a loved one, or a lost lover, or perhaps, from a near-death experience we lived through.

Mine just happen to be from all three.

These memories aren’t as pleasant for me as those first three events. After all, the circumstances were much different in every regard. Nothing about any of them could even remotely be considered “pleasant.”

The human brain has a tremendous capacity to remember the tiniest of details and store them away for later use. Sometimes, it stores them in the deepest recesses of our mind, in parts of the brain that are seldom accessed, to protect our psyché, and help us keep our sanity.

This article will address the impact of the first tragic event that brought about episodes of anxiety and depression within me that I still deal with daily.

My first tragedy came in May of 1967. The country was awash with a new phenomenon, the hippies. Their chant of, “Make love, not war” was in direct opposition to the Vietnam Conflict we were involved in, where over 2.7 million men and women would end up serving their country.

Two months after graduating from high school, in August of 1966, I joined the Army. I didn’t want to wait on the chance my draft number would be selected later on in my life, so I volunteered for 3 years of service, even though the minimum requirement was set at 2 years of active duty.

After six months of Basic training, Advanced Infantry training, and Airborne paratrooper training, I found myself on an airplane headed for Vietnam. It was February 15th, 1967, and I was 18 years old at the time. My assigned military occupation status (MOS) was 11B (Infantry). As I would soon find out, this meant my unit was routinely sent to the front lines to battle the enemy whenever and wherever we found them.

Six soldiers standing in a field with a 105mm howitzer belching smoke from its barrel.

My first introduction to war came on the second night I was in-country and was actually caused by a fire mission to support our men who were out on patrol. My "baptism by fire" came in the form of 105mm howitzer booming artillery rounds at known coordinates of the enemy.

There was a continuous barrage of shells hurled at them for a good 30-40 minutes. Then, everything became silent and all our troops went back to what they had been doing before the fire mission was called.

Some had been shaving, some had been eating C-rations, and others had been cleaning their guns, rifles, and ammo, while the rest of the men took a quick nap. We never got more than 20-30 minutes for naps, because there was always something to do.

Exactly ninety days after my arrival in the war zone, we were involved in another major firefight with the Viet Cong. To be able to have a near-total recall of all the turmoil and confusion of that day, especially fifty-five years after it all happened to me is incredible.

We had established a fire support base carved out of the jungle in a very wide, open field, large enough for our Battalion and the attached battery of 105mm howitzers to conduct fire missions in support of the many “search and destroy” patrols we would conduct, in an effort to remove “Charlie” (the name we used to identify the Viet Cong) from the surrounding villages.

Normally, we wouldn’t stay in a fixed position for very long. We would conduct clearing sweeps of the area, stretching our patrols farther and farther from our perimeter, until the distance between our troops and the base camp became too great to provide adequate defensive support. Then, we would move to a new location and perform the same sweeping action as before.

Having been at this support base for two weeks, we awoke early on May 17th, preparing to pack up and leave, abandoning the firebase after multiple search-and-destroy patrols had turned up relatively few Viet Cong.

Leaving a firebase meant we had to tear down and destroy whatever we had built to protect ourselves. We didn’t want to leave any supplies or utilities that “Charlie” could use in combat against us, so we emptied the sandbags we had used as a roof to cover ourselves directly into the foxholes we inhabited during our stay.

I had just torn off the roof of my foxhole and had started filling it in when a shrill voice hollered, “incoming,” alerting the entire battalion that mortar rounds were landing inside our perimeter.

The enemy must have planted a spotter in the trees surrounding us because the mortar rounds were very accurate. The explosions first targeted our artillery unit, then methodically advanced down the field closer to my position.

My job within our company was one of two RTOs (radio transmitter operators) for the company commander. The other guy was a fellow named “Smitty,” who had been performing the same tear-down task as me.

We both looked at each other and realized we couldn’t fight the enemy with shovels, so we threw them down and sprinted the 30 yards or so to where our weapons and radios were sitting, arriving simultaneously to latch them up and sprint back to our respective foxholes. Neither of us made it back.

As soon as I grabbed my rucksack and rifle, a 60 mm mortar round exploded in front of us, sending both of us flying through the air, separating us from our gear, and severely injuring us.

Smitty got the worse end of the blast. Unknowingly, he was facing the mortar round as it landed. I had been slightly behind him and to his left, which shielded me from absorbing a direct hit. We were both thrown through the air a good ten yards or so. We landed with a thud and instinctively started crawling toward our foxholes.

I had crawled about five yards when a second mortar round exploded near me, again picking me up and throwing me through the air another ten yards or so, where I landed half-in and half-out of my foxhole, which was now occupied by our commanding officer, Capt. Baugh, who had also been wounded in the blast.

There were three more explosions in other areas around the perimeter, then we heard small arms fire going off in multiple directions. Immediately, Capt. Baugh climbed over me and out of the foxhole to assess our situation and direct counter-fire to aid our troops on the perimeter.

After seeing the severity of Smitty’s wounds, he turned and asked me if I could walk. My right boot looked like a dog had chewed through it and I could see shrapnel sticking in my ankle. I tried to stand but fell backward. That was when I realized I had been struck in both legs, my side, and my back. Because of these wounds, I was unable to walk.

Capt. Baugh then ran over, picked up both radios and my rifle, and brought them back to me. He took Smitty’s radio and started to head toward our perimeter but turned suddenly and told me to contact battalion command and let them know about our wounded, then switch my radio back to our company’s frequency and let him know if there were any instructions for him to follow.

I called battalion command and let them know about our wounded and was immediately transferred to the battalion commander. Everything became crazy quiet when he picked up the receiver. No more explosions or small arms fire could be heard.

Then, the C.O. asked me why I wasn’t with Capt. Baugh who was on the front lines and I explained that I was one of the wounded and couldn’t walk. He instructed me to call in “Dust Off” choppers to pick up the wounded for transport to a field hospital so we could get treatment for our injuries.

(Silhouette of a man holding a lit, red smoke grenade.)

It was about fifteen minutes later when the first chopper landed, rotors still revved as if to take off, in case “Charlie” tried to spring another surprise attack.

There were injured and dead scattered around the ground, so each unit had to pop a colored smoke grenade to direct the choppers where they were needed. The artillery unit was hit very hard and used green smoke to guide the med-evac teams where to land.

Another company had endured several losses and popped a yellow smoke grenade for their chopper. These pilots were exceptionally good at landing, getting the dead and wounded loaded, and getting back in the air in less than five minutes' time.

My company used red smoke for our landing spot. I popped a can of it and threw it far enough away so the prop blast wouldn’t blow up a ton of dust. I could see more choppers coming toward us, then heard my call sign being called out on my radio by one of the pilots. His call sign was “Cowboy two-niner” and he sure was a welcome sight for sore eyes.

He landed the chopper and we were carried over and loaded onto it — Smitty on the top rack and me on the bottom on the front side of the chopper and two more wounded soldiers on the rear side racks — and we took off for what I later learned to be Black Horse Field Hospital. Exactly where it was located, I haven’t a clue.

(Dust-off Huey helicopter used to transport the dead and wounded from the battlefields.)

During the twenty minutes it took to get us to the hospital, I held Smitty’s hand and kept talking to him. His entire face and chest had absorbed hundreds of searing hot shrapnel pieces and his pain level was excruciating. He kept telling me, “I don’t want to die.” I did my best to reassure him the Army doctors would take great care of him and told him to keep talking to me.

When we finally landed at the hospital, he was immediately whisked into surgery. Time was critical for them to get his bleeding under control. It took them four hours in surgery to get him stabilized well enough to transport him for better care at the hospital at Long Binh, close to Bien Hoa airport.

The remaining wounded still in triage were advised by the nurses that their supply of morphine had been used for all the other more seriously wounded soldiers. They explained this as they delivered two aspirin to each of us to help us manage our pain.

Our battalion had sustained four KIAs and sixteen wounded during the morning attack, so the operating room, which only had two operating tables, was kept very busy. It was nighttime before I reached the operating table.

As the orderly transferred me to the table, the surgeon explained to me that there were no painkillers remaining and he would have to dig out my shrapnel as best he could but didn’t give me any indication of what that entailed.

He had a nurse standing at my head as I lay on my stomach, arms extended straight over my head. He instructed the nurse to grab both hands and pull down, to keep me from moving. Then, he told the orderly to stretch his body across my torso, to keep me from moving my legs.

As he instructed me not to move, he started pouring rubbing alcohol into each wound and slowly inserted some forceps into each wound to search for the shrapnel. The burning pain from these procedures was unlike anything I had ever experienced.

It took intense concentration and physical effort to keep from moving my legs as he dug into each wound searching for shrapnel. The body instinctively tries to move away from whatever pain is being inflicted.

As the surgeon started digging into my left shoulder, I must have passed out because, the next thing I knew, it was the next morning and there was an artillery major standing at the foot of my bed telling me how I had thrashed around in my sleep all night long. I have no memory of this at all.

After he walked away, I started taking a mental inventory of what was still hurting in my body. A nurse stopped by and told me I was going to be sent to Long Binh Hospital for further physical therapy on my ankle, which was swollen to more than twice its regular size.

All the beds in this hospital were filled with wounded soldiers and they were sure to get more wounded each day. So, around 10:00 a.m. they loaded me into another chopper for a quick 30-minute ride to my next hospital stay. I would be confined to this hospital for seven more days, with multiple trips to physical therapy each day.

During my stay, I had several dignitaries visit me. A brigadier general stopped by on the second day to pin a purple heart to my chest. But, on seeing I was shirtless, as all the wounded were because of the heat — the hospital wasn’t air-conditioned — he pinned my medal to my pillow.

On the third day of my stay, I asked if I could visit Smitty, who I had learned was in a different ward. They brought a wheelchair, put me in it, and wheeled me to intensive care. When I saw Smitty’s condition, I was amazed he was still alive.

His face and chest were still pock-marked with all kinds of shrapnel. He had tubes running in all different directions, but he was being given morphine and was able to let me know they might be shipping him off to Tokyo, Japan for better treatment. I told him I’d be praying for him and hope he got better soon, then was wheeled back to my bed.

When I asked to check on him the next day, they advised me that he had, in fact, been flown to Tokyo for more surgery. I never got to talk to him again.

Then, on my 5th day in the hospital, my next visitor came and sat next to my bed and talked with me for five minutes or so. She asked me if I knew who she was. She was easily recognizable, but I flubbed her name. I told her she was “Dear Abby,” but she quickly corrected me by saying, “No, I’m Ann Landers, but Abby is my sister.) So, I was close, but no cigar.

The physical therapy treatments were twice a day, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. As it turned out, my right Achilles heel had atrophied on me from non-use. When the second mortar blasted pitched me into my foxhole, I landed quite awkwardly, with my right foot under me and to the left. When I tried to move it or flex it, I was met with unbearable pain, so I kept it stationary as much as possible.

In physical therapy, I used a system of pulleys to pull and stretch my Achilles heel back into shape so that I could put some weight on that foot. It was an arduous process, but on the eighth day of my stay, my release date, I was able to walk without the assistance of a crutch, or cane, although I still had quite a significant limp.

As I was released from the hospital, I walked out with my left boot on, and my right boot held in my hand. A nurse asked me to put my boot on before leaving and I told her my ankle was still too swollen for it to fit and I still had metal stitches holding my wound together.

She quickly consulted one of the doctors and they assured her I was good enough to be released. She told me I could pull out the stitches in my legs, my side, and my back on my own after another three days.

Little did I know back then in 1967 that this tragedy would be so deeply embedded in my memory to this very day — and I consider myself one of the very lucky ones who got to walk away.

(The poster shows the back of an Army soldier walking through a parking lot. Superimposed on his body are the words: June is PTSD Awareness Month.)

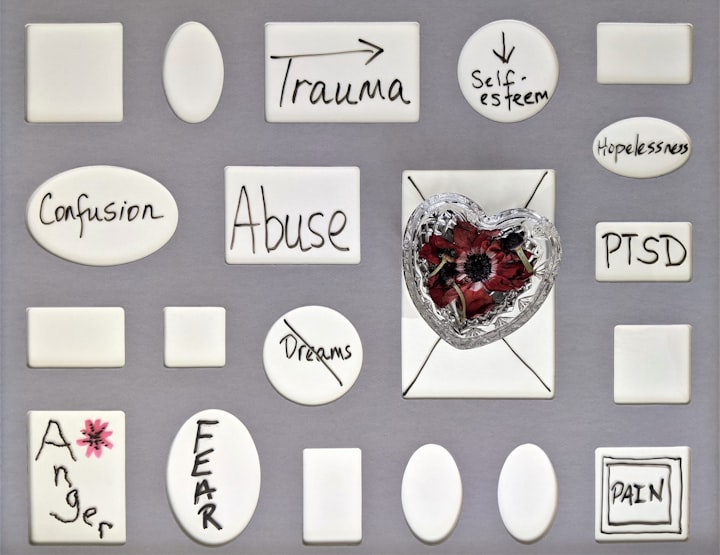

One thing I realized very quickly about Post-Traumatic Stress is that I really can’t totally control when it will happen. There is no telling when or where it will rear its ugly head.

I can be outside working in the yard and hear the faint sound of a helicopter’s blades chopping through the air, and I am immediately transported back in time to a day in Vietnam where I experienced something similar to this. Or I can see or hear the rustling of leaves on a tree, or I can smell diesel fuel. Any one of these can propel me to the past.

The one thing I can control from all of this is my personal reaction to being thrust back in time so rudely. I can take, or avoid, certain actions that are usually catalysts for this happening.

In order to have these flashbacks under control, I have gone through extensive counseling ever since I recognized these flareups were occurring regularly in my day-to-day life way back in 1980. I have participated in group sessions as well as individual sessions. I have gone through several multi-step programs to help me become comfortable in certain challenging situations.

One beneficial activity I have accomplished is to be mindful of the present, meaning right now, the day and time I am living in and experiencing. When I have mental lapses back to the past, I find it helpful to remind myself, “that was then, this is now — I don’t live in the past anymore.

I am not always successful at this endeavor. Sometimes, when I am driving, I can see something or perhaps I hear an old song that takes me back to Vietnam again. The next thing I know, I’m 20 miles down the road wondering how I got there. Times like that are still very troubling to me.

While these flashbacks are now commonplace for me, when I return to the reality of my present day, I have found it very important to identify what set of circumstances was existent at the time of my transport, what transfixed me from today to something that happened so long ago.

My logic is simple: If I can find the root cause of what sent me back in time, I may be able to develop a strategy that helps me avoid that situation in the future. Otherwise, I can’t affect the changes necessary to keep these events from reoccurring.

Having a reaction plan to a post-traumatic stress event is extremely important in trying to establish some semblance of control of the circumstances happening in my life. I gain more peace knowing that I can control my reaction to adverse events — it helps me return to the present, today’s reality, much quicker.

Thanks for reading this!

© All rights reserved

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.