The War On Photography

A War Photo-Journalists Story

WHOOSH, a bullet barely misses me, and I hear a voice yelling at me to "GET DOWN." Bullets riddle through the sky at the platoon that is taking cover from enemy fire. Smoke and a dirt tornado swirl up as I grab my camera and get into a flat prone laying-down position to get pictures of this dirt tornado and soldiers' platoon.

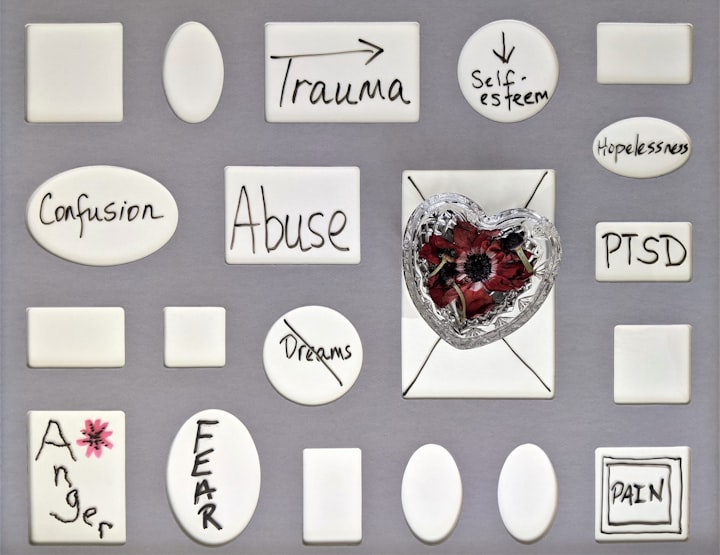

Never in my right mind would I have thought that after getting my degree with the New York Institue of Photography, and enlisting in the Army reserves, would I be in combat and taking photojournalism to this level. I was dodging bullets and jumping into foxholes, capturing the very essence of what this war is doing to our soldiers. How when they come home are more broken emotionally and physically. How to some soldiers home to them is being on the battlefield, because they can't cope with civilian life. They would rather be strapped with a hundred pounds of gear, and an assault rifle or their M-16 rifle and protect us from abroad in a country where most people have a hard time trying to pronounce its name.

More bullets fly overhead as I zoom in on some soldiers doing a break and entry of a building so that the soldiers could get to higher ground and lay down a field of suppressive fire on a mountainside to take out a Taliban sniper and enemy troops. Finally, there seemed to be a break of bullets being fired. I was able to go through and look at the pictures that I took with my Canon Rebel T7 mirrorless camera, with a 24-70 mm f2.8 lens 1/1000 speed and ISO of 200. I wiped off the 4-inch LCD screen and zoomed in on some of the pictures' details and see what my instructors, family, and friends saw in my photography. The preciseness of my photos without the use of a tripod to take the most amazing pictures.

The Army helmet juggled my head as I remembered that day that my cousin, Stephanie, told me about skillshare.

"Joe, Skillshare is a learning platform where you can learn virtually anything. It's like going to college and doing workshops and assignments for $9.99 a month." I could hardly believe it, so I signed up and found out that I got it for free for the first month, then after that, it was $9.99 a month. I had always wanted to learn photography, and my mother always told me that I took pretty good cell phone pictures. I took every fundamentals course and every other photography workshop that I could, and I was soon taking professional quality pictures in a matter of weeks. Within three years, I had opened up a photography studio and was taking professional photos.

My pictures were getting national attention, and I got approached by a recruiter who asked me if I would want to be a combat photographer. To show people the other side of what they think war is about. It's not how Hollywood depicts it. I have pictures of combat medics injecting soldiers with needles of adrenalin and other combat cocktails to get soldiers up and back into their command posts' safety. I have pictures of combat nurses of both men and women caring for the wounded and applying bandages to soldiers' wounds that covered their bodies. If you're not comfortable seeing blood, grey matter from soldiers, brains, or bones broken, you learned to develop a strong stomach real quickly so that you weren't puking and contaminating our command post. Sometimes a urinal wasn't always available to get sick in. The smell of fire didn't help matters either. It was a rather pungent smell that you couldn't get out of your nostrils.

I have pictures of blood spitting out of bullet wounds and photographs of soldiers teaming up to carry soldiers on there back or over there shoulders. These Army soldiers never left any soldier behind. There's one picture I have of a very, large guy with his arms over the backs of two other soldiers helping him walk as he limped with a tourniquet on his right leg towards a helicopter. The dirt and the dust stirred just right underfoot, creating a fabulous picture. Being on the front lines of this war and capturing scenes of grotesque images, I had to learn and develop a strong stomach and also be quick with my camera. I couldn't miss a shot. I had fellow Army snipers give me the nickname photo-sniper because I could take a picture of a Taliban soldier 1,000 yards away with an 800-millimeter lens with a 1.5 lens magnifier, which means that I could zoom out to 1,600 feet. It made me feel like I was a part of the most elite of the elite shooting teams.

I hear the soldiers shouting "clear" as they broke through the door and cleared each room to ensure that it was safe for me to follow. The camera up to my eye and on auto just seemed right. I didn't want to be messing with settings to make the perfect picture, adjusting the f-stop and the aperture and the iso. Two soldiers were backlighted as they each took cover behind a window. One soldier pointed his weapon to the left, the other soldier to the right. Snap. I took their picture; it was a perfect shot.

I look towards the stairs, and a soldier was each strategically placed and covering the way for me to climb and enter the second floor. I find a position behind an open window to look out of with my lens. I thanked God for the equipment that I had that shrouded and protected my lens from reflecting my position to enemy Taliban soldiers. I gave the lens a quick turn to focus the lens, halfway push down on the trigger button, the lens makes a quick adjustment, and I get a picture of a helicopter flying to the top of the building that we were in for extraction.

The soldiers provide two by two cover as each soldier climbs into the chopper, and it flies us back to our command post. I click into a static line so that I don't fall out of the helicopter, and I lean out a little bit and take a picture of our command post before we set down. Back down on the ground, the soldiers go and report back to the commander and how far they got in clearing each building for Taliban soldiers. I go back to my tent, take out my sd card, upload the pictures I took to my laptop, and see what they looked like on a full screen. They all turned out fantastic even though they were graphic in grotesque ways.

One picture was of a Taliban soldier being obscured as a spike was being driven into him as he fell from a rooftop after being shot. He landed on top of this wooden spike through his stomach and out through his back. Another picture was of a Taliban soldier falling into the perimeter razor wire as he was running with a suicide bomb attached to his chest. A sniper took that shot just a few feet short of this Taliban soldier, almost breaking through our defenses. That could have been even messier if that Taliban Soldier would've made it past our defenses and blown himself up with some of our soldiers. Luckily we had that sniper in a church tower that was covering our post.

A few other shots were of four soldiers walking down from a hillside after sunset and seeing the silhouettes of them as they walked back towards our base. Another picture that I was proud of was of an M1 Abrams tank. One of the most significant and badest armored vehicles as its six-inch cannon was pointed towards the sunset. A few soldiers had come into my tent and had wanted to see some of my pictures. I turned on the projector, which was an even bigger screen. The pictures I took didn't pixelate as I always shot my photos in a large raw format. The soldiers sat on an extra cot and watched the slide show of pictures being broadcasted from my laptop to this seventy-two inch by seventy-two-inch screen. I tell the young first-time soldiers who are here on there first tour that if they have a weak stomach to not come into my tent when I'm doing minimal editing of these pictures, as you can tell that most of them are very graphic. Not all photos are explicit, but some are so I can have a decent war picture portfolio to bring back to the states to show my work and get a job as an ordinary regular portraiture or wedding photographer. I lucked out to not have a weapon other than a canon rebel t7 mirrorless camera. I don't know if I would have had what it takes to shoot and to kill someone.

Specialist Ricks jumped off the cot as the screen went from a picture of the American flag to a picture of one of the deadliest snakes. A King Cobra who's known for its venom has enough neurotoxins to kill an Asian elephant and about 50 percent of the humans that it bites. It can reach up to 18 feet (5.5 meters) in length; the king cobra is also the world's longest venomous snake. I saw it crawling along the desert floor one afternoon. I laid down on the ground and aimed my camera and 300 mm lens, zoomed in on its face, and as it curled it's head up to smell the air with its forked tongue slithering in the air, with the lens that I had, you could count the scales in its head, and it's body from my point of view. It was beautiful in its coloring of browns and black scales. It fanned out its body to capture a breeze then shrunk back down to the earth. I took its picture at its peak when it fanned out and before it slithered across the road. Some of the other soldiers laughed as Specialist Ricks walked out of my tent. I tell the soldiers that there are pictures of some of the deadliest animals in my photography. If the soldiers are squeamish about such animals and there eating habits not to enter my tent. It's quite impressive watching a snake dislocate its jaw to swallow its prey. I have a picture of a hippo stretching its jaws out, which is a remarkably two feet in length from lip to lip. An adult hippo's mouth is roomy enough for thirty-six teeth, including tusks that can grow up to two feet long. I have been told that some of my nature and wildlife animal pictures are note-worthy to be in National Geographic.

I can hardly wait until my term of service is up, and I can follow my dreams of being a wedding and portraiture maybe even a boudoir photographer. I imagine that I will always have a camera in my hand no matter what I am shooting. I love photography and the support that I get from family and these American soldiers.

We all hear the whistling of a mortar round being fired towards our camp. Someone yells, "INCOMING." All of us grab our helmets and dive down to the ground. It wasn't far off from almost hitting my tent. Twenty feet more, and it would have struck my tent dead on. The soldiers grab there M-16's and assault rifles and low crawl out of my tent to foxholes that they had dug. I grab my memory card out of my laptop and insert it into my camera and low crawl out my tent to the foxholes to see the soldiers returning fire towards the mountain at our compound's back. The enemy was trying to flank our position and blow up our command post. I fumble with my camera for a second and eventually get it turned on, just as our troops return a couple of mortar rounds at the mountainside. I rise slightly up, aim my camera at two of these soldiers, positioning the mortar and a third soldier grabbing a mortar round and dropping it into the mortar firer and whoosh just as it goes off, I take their picture. Another three soldiers who could have been football quarterbacks grab three grenades, pull the pins, and throw them a good hundred yards away.

Boom boom boom, smoke rises from the grenades, and the mortar round as I snap the picture and my camera being on auto-focus, I see a Taliban soldier. I yell out where he is, and the American troops lay down suppressive rounds of bullets. I zoom in on the Taliban solder's position and see bullets rip through him and his head. I yell, "you got him." The soldiers scream and hoop and holler, HOORAY. A couple of soldiers cross there M-16's over the other, and I snap the picture. One of the Soldiers was Jack. How I knew that was that he had a Joker card in the band of his kevlar hat. We all called him Joker as he was always telling a joke and making us all laugh when we needed moments of laughter instead of bullets being fired through the air. Another soldier had the ace card in his band on his Kevlar helmet; we called him Ace. We all had great camaraderie with each other. We all had each other's backs. I know I didn't have an M-16 or an assault rifle, only a camera, but I learned how to help our troops during this war.

After things settled down, we all made our way out of this trench that was surrounded by razor wire and sharp poles sticking out, and each soldier made his way back to his position that he had to guard for the rest of the night.

Everyone's blood pressure and heart rates had gone done after an hour from the firefight earlier, and we were able to relax and finally able to eat our MRE's. Meals ready to eat, or meals on wheels because some of them made you feel like you were running to the bathroom. The spaghetti mre was pretty good. The Salisbury steak tasted like dehydrated beef jerky, but other than that, it was reasonably decent to eat as well. The water tank was our refuge; we would frequently fill our canteens with fresh water. The brownies were always a success to eat. You would think that we would look like a couple of cowboy Marlboro men protecting our country, but we didn't. We all stayed in excellent shape for running for cover when the enemy would start shooting their guns at us. There were a couple of soldiers who smoked Marlboro cigarettes. We often teased them about it.

Everyone who smoked had their different brands and were only allowed to smoke in certain areas where snipers couldn't see them. I had taken a silhouette picture of a soldier who was smoking his cigarette that had turned out pretty impressive with the smoke curling up and forming a circle as he breathed out the smoke from his mouth. I had thought about smoking but felt that I shouldn't. I should keep my lungs in good shape to run and exercise when we were allowed to workout. Sometimes some of the soldiers had their cigarettes under the band on their kevlar helmet and would frequent a quick smoke when they could. I remember taking a picture that resembled some images from world war one and world war two of soldiers having lucky strike cigarettes in their helmet band.

I finished the spaghetti mre and had to take a dump. Another thing about eating the MRE's was that they kept you regular but without diarrhea. I found a porta-potty and did my business. What was nice was when they set these porta-potties out, they illuminated the inside of them so that you could scope out the seat and the interiors so that you didn't get stung by scorpions or bit by any snakes that wanted to feel the warmth from the crap inside it's holding tanks. I finished my business and went and grabbed my camera from my cot.

I was hoping to catch a picture of the moon and the stars against the mountains and the desert. I lucked out though, with a moonless night but had some bright stars. I focused my camera on infinity, bumped up the iso to 3600, and adjusted the f-stop to f-32 and the seconds to the bulb feature. I found the ideal shot with the mountains' landscape, found my shot, and took it just before an Army medic helicopter came flying in low to land.

I jogged around the perimeter of razor wire and trenches to capture a front end view of the Army medic helicopter with its lights flashing and whooshing of the blades pushing air down. It created a tornado of dirt as it started to land. I aimed my camera up at it adjusted the iso to 100, the aperture f-stop to f-5.6 and 1/10,000 of a second, and captured the helicopter and it's blades as if frozen in time. They were life flighting a couple of soldiers from our command post to a nearby hospital where they could be treated. The Army doctors and nurses were covered in blood as they carried these soldiers on backboards and with iv drips of sodium and other medications and pain meds as well to the helicopter. The teamwork and the efficiency of these Army medical staff were just amazing to watch. Much like how it is when you are watching Nascar. You have a whole pit crew of people each doing something valuable to get that car back out on the track as soon as possible so that they and that driver can get back out on the way and in an excellent position to take first place. However, there was no trophy for saving these Army soldiers' lives in the middle of a war. It makes it seem like a thankless job.

I always make sure I thank the doctors and the nurses for there service. I shot a couple of profile pictures, which turned out to be silhouettes, but they still turned out amazing, despite that it was our troops' being life-flighted to a hospital. I said a quick prayer of health and healing and strength to be upon our soldiers and for God's hands and angels to be upon them.

It was getting late or rather early in the morning from me chasing down the medivac chopper to get a fantastic aerial shot of the helicopter flying low, almost 03:30 am. I walk my way back to my cot and try to get a couple of hours of sleep. The second my head hit my pillow, I was out cold. The weather was perfect for sleeping; it wasn't too hot, and it wasn't too cold, it was just right. I slept hard and had weird dreams of being caught in the middle of the enemy and our American troops. It was dawn in my dream. I'm seeing flashes of troops advancing in on my position. They were crawling through trenches and swimming through ponds with M-16's just barely above the waterline. The troops were dodging black and brown scaled water mocassins and getting ready to fire their weapons at me. I look down on the ground, and instead of seeing my camera, I see an M-16 assault rifle. I pick it up and look through the scope and make my shots clear and precise and start shooting both the enemy and the American troops.

Suddenly I'm jarred awake from an explosion and a soldier flying over my cot through the tent. If that mortar round were fifteen feet closer, the medics would have been cleaning my up body with sponges and toothpicks. The soldier that was walking through and doing guard spot checks along the fences was the one that went flying through my tent. Rattled, I manage to get my kevlar helmet on and lay down on the ground and cover my head with my arms so no shrapnel would hit me. I wait for ten minutes, grab my camera, and low crawl out my tent.

I could hardly hear anything. My ears were ringing so badly, but once outside, troops were running and taking cover in the foxholes and trenches. It was as if the gates of hell had opened; enemy troops were parachuting into our command post and firing their weapons and dropping grenades on the American troop's tents. Soldiers were screaming in pain and agony and thrusting there hands over bullet wounds that tore through their flesh—blood spitting from their injuries. Arms, legs, and necks are broken from being flown across the desert floor from the grenades' impact.

I tried to capture some of these horrific scenes with my camera. Still, once you see such horror and panic and blood, it's hard to function on anything that's past your reach, and my camera felt like it was beyond my reach even though I was holding it, it felt like it was a million feet away from me. At the most of what I could do was scream.

The soldiers started firing their weapons back at the enemy troops that had parachuted in our post. I had low crawled to one of our trenches and found an American soldier dead. I said to myself, "screw this shit." I grabbed his M-16 and his 9-millimeter handgun and crept up towards the rim of the trench. There was enough daylight to tell the difference between the enemy troops and our American troops. I had been through enough classes and took pictures of soldiers assembling and disassembling their weapons to figure out how to cock, put the gun on semi-automatic and look through a scope. Much like the dream that I was having before this massacre happened. I saw one of the enemy soldiers put his head center mass with the scope and fired. His brains went flying through the other side of his head. After that, I vomited and lay down in the trench, covered myself up with two dead soldiers, and aimed my camera up at the trench's top.

Our troops had the enemy on the run towards me, but I wasn't a soldier, I was a combat photographer. As the enemy troops approached the trench, I aimed my camera through the pile of the two dead bodies on top of me and captured a fantastic shot of these three enemy soldiers being shot and blood flying out of there chest. Some of it hit me, but I kept shooting pictures as these enemy troops' bodies fell in the trench around me.

Sometimes you have to do the most unheard thing to get some of the most fantastic photography shots. I was one of those photographers who would do anything for a great shot. It's what has separated my photography from other photographers. The phrase, you got to think outside the box to be successful, exactly means that. Except with photography, with photography, you got to think outside the lens, what are you capturing along the edges. That's the difference between being successful and unsuccessful.

I hear Ace call for me. "Casey," "wolfman," where are you? I holler out, "I'm here." I slowly crawl out from under the pile of dead bodies as Ace watches me. "Dude, your fucking wild, crawling under a pile of bodies to make sure you and your camera survive." He reaches down with his right hand to pull me out of the trench. We give each other a quick buddy hug, and I said, "I got him." Ace replied with a "what." I take him over to the body that I shot and showed him what I did. Ace said, "No fucking way." I told him exactly what I did and what happened. Apparently, it was the enemy commander and the deciding factor of the enemy retreating giving our troops the advantage to finish off this short battle.

I asked Ace, "did you call me wolfman?" he said yes, you remind everyone of a wolf, steady, consistent, singular but works with the pack, your determined and fierce. You face and stare at any problems until they either go away or are eaten. Just as we start laughing, an enemy sniper's bullet punches and punctures through Ace's throat. He collapses in my arms. I already knew that he was dead. I grabbed him by the armored flack vest and dragged his body to cover.

I hide behind the water tank truck and sneak around a couple of tents with my camera. I go to my tent and grab my 800-millimeter lens. I attach it to my camera and start scoping out the hillside, nothing. A platoon of soldiers was holed up in one of the buildings seeking cover and refuge and to bandage the wounded. I get to the top of the stairs and see eight soldiers. Two covered up, three soldiers taking cover away from the windows, the commander talking to one of his lieutenants, and a radio operator calling for a zone strike after laser pointing a grid to take out the remaining Taliban soldiers. Well, we could at least hope that it was the remaining Taliban soldiers in this sector. I go to the back of the room and aim my eight hundred millimeter lens with my 1.5 lens adapter, and I'm able to zoom out to sixteen hundred feet with it towards where the snipers are at. I tell the radio operator where to target the drop zone for the bombs to hit. He radios it in, and within minutes a drone does a fly by and drops a bomb. BOOOOM, WHOOSH, we wait a couple of minutes. Some of the soldier's fire there guns out that way and then seek cover.

Nothing. We figured there must have been at least three snipers that our drone attack got. I looked through my lens and didn't see any movement.

A couple of troops and I went out and scouted the area. The only thing that we saw was charred trees, and smoke trailed off in different directions from the wind. The further in that we investigated, we finally saw the three snipers body disfigured and bodies charred black. I walked back about fifty feet so that I can use the wide-angle lens that was on my camera and took a shot of the aftermath of one of our bombs being dropped. It reminded me of the progressive Flo gal selling insurance for some reason. No matter, wind, hail, snow, or rain, we'll protect you and your belongings.

I knew within some comfort that if I needed, the Army would replace any lens or camera if I had anything like fire, theft, or damage to my photography gear. But I also knew that I could get photography insurance through an organization called North American Nature Photography Association. Their prices are very reasonable. They range from $25.00 to $270.00, depending on what kind of photography insurance you’re looking for. Even if it was under wartime situations, I am sure that I could call North American Nature Photography and have all my gear covered. I was thankful so far that all my lenses didn't have any scratches or breaks in the lenses. My camera was still working, so everything was still good in my world.

I lightheartedly joked that those three enemy snipers should have gotten bomb and fire insurance. The other soldiers chuckled, and each thanked me for what I did and shook my hand. If it weren't for me and my bravery, we would have a different outcome right now. The captain and lieutenant agreed and told me that they would send it up to the commander that I get and be recommended for a bronze star for my gallantry and bravery. Here I am with only a camera, and I was instantly humbled and got down on my knees and said, "thank you." We walk back to our command post, gather our dead put one of there dog tags in between there teeth, and kick there jaw shut so that the coroner would know which dog tag went with each soldier. We calculated our loses, twenty dead, ten mortally wounded. The medics were like superheroes, between giving iv's and saline drips and wrapping wounds and digging bullets out. If anyone ever deserved a blood-stained red, white and blue cape, it was these people trying to keep our mortally wounded alive.

Our radio-operator called in two choppers to take our wounded back to a hospital where they can be better treated and give our combat medics a chance to breathe. I don't think none of them had slept for two days straight.

I, of course, grab my camera and take some pictures of the two medic choppers flying in. One of the ground crew members shot a flare-up in the sky where the helicopters were to land. The medics and some of the other soldiers helped them load the stretchers that had our wounded on them and locked them in place. Within five minutes, all were loaded up, and the choppers were taking off. Six soldiers were walking back from the choppers landing zone, and with the smoke from behind them was the perfect shot. They looked like a bunch of firemen, brothers, arms over each other shoulders, and walking back together and had to be one of the most impactful pictures that I took.

Every once in a while, you can shoot a photo and ignore the rule of thirds. Which is taking a squared piece of paper and folding it in thirds from top to bottom and from side to side, and you come up with four points. For the best shots, you want to not center the subject that your shooting but rather to the side to either the first and third spots or the second and fourth points.

When looking at the rule of thirds, the bottom third is the foreground, the middle part is mid-ground, and the top third is the background. When you know where the focus point is of the picture in the middle of the image you want, it is called the focal point. From there, you can see where your depth of field is. The depth of the field is the center point of the picture is the top of a pyramid and bringing the angles back at either thirty or forty-five-degree angles. You would use this tip if you wanted the bottom and forty-five-degree angles to the imaginary tip making a pyramid blurry all around it except the area that makes a triangle. Very rarely have I blurred out the whole picture to show this feature of photography. Seeing the whole picture and around the edges makes the photo. It reminds me of a saying growing up as a child, "Don't look at what is in front of you, but what is beyond you." Ever since then, I have always reached towards the stars in whatever I have done. I always looked at the bigger picture, the end result.

Never in my military career as a war-time photographer did I think that I would get a bronze star for my bravery and gallantry to save Ace. His memory and blood still clung to my clothes and my hands. One of the sergeants finally came up to me and told me to get cleaned up, but all I could do was well up with tears. Ace was a good friend. He was like a brother. I couldn't get past my own emotions to see his corpse one last time before we shipped off the dead on a chinook. The best that I could do was think of him as in the bigger picture that he was on his way home.

Sixty days left of being here in this hell of blood-covered sand, and all I could think of doing for him was salute the chinook as it flew away.

I finally filled my canteen up with water and took a long drink of it and let the water splash out over my chest. It felt cold and refreshing. I felt like I could kill for a hot shower. I opened the water spigot some more and washed my blood-soaked hands and chipped fingernails. I went and grabbed a travel size shampoo dispenser, stood behind the water truck, and washed my hair with cold water. It may not have been a hot shower, but it felt good to have clean hair. I wished I could have shaved. Now I understood what Ace said when he said that I resembled a wolf. I was freaking hairy. I hadn't had a clean shave in over two months. When you were on the front lines like we were, we didn't have the amenities of hot water or running water. Showers were basically a spit bath with a washcloth and a little soap lather up and rinse off. I could hardly wait for the next 60 days to be over with. But I did love what I was doing and taking combat pictures.

My instructors would probably fall in love with my combat pictures and recommend them to put in magazines like Time, National Geographic, The Smithsonian, Outdoor Photographer Magazine, and a few others that I can't think of the top of my head.

I felt the ground underneath me start to shake. Like a tremor impact when actor Jeff Goldblum said, "hey do you guys feel that," in the movie Jurassic Park. When the Tyrannosaurus Rex was closing in on their position. When you feel the earth tremble under your feet, you feel like the shaking will knock you off your balance, especially when you feel an M1-Abrams tank drive past you within fifteen feet away.

I grab my camera bag and my canon rebel t7 with my 24-70 millimeter lens with its f-stop at it's widest point is a 2.8. Meaning the wider the lens, the more the light comes in. It's an ideal lens for everything because you can shoot up to eighteen inches for a macro shot or zoom out to its regular 70-millimeter lens. With the 1.5-millimeter zoom attachment, I can zoom out means I can zoom it 1.5 times longer than the usual 70 millimeters to shoot out towards 140 meters. Much like when I use the 800-millimeter lens to spot out a sniper, it will shoot out 1600 meters.

I follow behind the tank by thirty feet because this tank is like the behemoth of all tanks. The soldier who drives the tank down the street of the compound that we are in, I see the perfect lighting—the sun out in front of it and to the right, forecasting shadows on the adjacent building. I get into my settings and switch it over to monochrome to shoot in black and white. When there's too much light, and plenty of interesting shadows makes for excellent black and white pictures and presents an interesting contrast between the black and whites. I leave the metering setting (where the amount of light is being read in your photographs) on the evaluative setting. That way, the amount of light is being read for the entire picture. The center weight is the amount of light being read from the center point of the image and spot reads from the light from one spot. So it's always for the best to leave my camera in the evaluative setting. I switched my camera back over to standard settings and shoot a profile view of the tank. Because it had a United States flag on the back of it blowing in the breeze as it drove down the city streets, I see the perfect shot of this huge tank's profile and the flag flying, and it was just a fantastic shot.

After taking my few shots of the M1-Abrams tank, I walk back to my tent and get the fixings to make myself a pot of coffee. I try to relax by continuing to watch the sunset without any interruptions of being fired at again. You would think that by drinking so much coffee that we wouldn't sleep, but it was the only stimulant that we took to keep us on edge, especially if we needed that jolt of caffeine to keep us going like the previous days' battle. After being as active as we all were, none of us had no problems getting to sleep. But that proved to be our vulnerability. So a couple of soldiers volunteered to keep watch all night with night vision goggles on. The soldiers rotated shifts every eight hours. So that our command post always had fresh and alert soldiers watching the razor wire perimeter and two guards in a watchtower overlooking the skies for paratroopers. We all learned our lesson quickly, not to be vulnerable, thinking that the enemy soldiers would fight fair.

I reset my tent and cot and felt like and wondered if I should sleep with my helmet on, but it proved to be more uncomfortable than anything else. I let my head hit my pillow and allow myself to fall asleep. It took me a while to fall asleep. I had thought of some of the wildest ideas of our soldiers flying and taking out the Taliban soldiers. I knew it wasn't all science fiction novel stuff; we had the technology for jet packs. Our troops could have jetpacks on their back, but how would they shoot the Taliban soldiers and maintain control of the jetpacks? Not unless someone was able to control the jetpack, much like how they control drones. We have people in Washington D.C. flying the drones remotely, so why couldn't they come up with the technology to do the same with the jetpacks. My mind wondered about this for about 5 minutes, and before I knew it, I was in dreamland thinking I was wearing a jetpack and flying and taking pictures of this war from above. It was the weirdest dream ever thinking that I could fly. Then thinking that I was hearing rotors coming from my jetpack, I wake up and hear the rotors of a couple of helicopters flying in.

I looked at my cracked watch-face in disbelief as I had slept heavily for 7 hours. It was the most replenishing sleep that I have had since I been here. I grab my camera, put the strap over my head, put my helmet on, and walk out my tent to see a couple of helicopters hovering above the drop zone. I see soldiers hooked into there static line and there feet on the skid, and the next thing I see is these soldiers repelling from the helicopter from both sides of the chopper. I aim my camera up at this amazing two by two cover formation of soldiers repelling from two helicopters was just amazing to see. I was glad that I was awake to capture this scene with my camera.

Sixteen total soldiers were coming in to help replenish our troops so that some of them could get a decent meal and some much-needed rest and possibly a hot shower and shave. I wish I could be on this recycle list, but I didn't have any backup photographers coming into relieve me. There was a soldier Sergeant Maxwell who had an excellent camera on his cell phone. But I politely told him that I don't mind staying and using a bigger lens like my 24-70 megapixel lens as compared to his 1.2-megapixel camera lens on his cell phone.

I didn't care what kind of pictures he could take. The comparison between the two lenses spoke enough more to me than anything else. And it's one of my biggest pet-peeves of people snubbing out real photographers because they think that they have enough talent to take pictures with there cell phones. These people have little to no skill and don't know what ISO is or the f-stop (aperture). They can't switch their camera over to straight monochrome. They desaturate the color, which still leaves some color in the picture for a black and white image, you may not see it, but it's there.

Also, the difference between shooting with a cell phone camera and a regular camera is the pixel size. I can shoot in large raw jpeg and have a huge photo that I can print that won't depixelize like a cell phone camera. People can only blow up a picture so much before it pixelates from a cell phone camera. Sergeant Maxwell tried to show me some of his photographs. I look but am not emotionally moved by his photos. Some of his macro shots were nice but not great. I show him the picture on a larger screen of the King cobra that I took, and he was stunned with the incredible detail of the snake's scales and its eyes. He responded with, "wow!!, I couldn't get that much detail from my camera on my cell phone. I would have to be really close to get that detail of a picture."

So I explained to him that lens sizes does matter when it comes to combat photography or any other kind of photography, and sergeant maxwell agreed that yes, it does, and he could clearly see the difference. I told him that I appreciated his gesture again, and politely said that I don't mind staying and continuing to take combat pictures of what was going on around us. I put the six-foot by six-foot viewing screen back up and attached my computer to it so that sergeant Maxwell could see all the pictures that I have taken so far. In the time that I had left to go to the bathroom and get a mre to eat, sergeant maxwell had come out of my tent in tears.

"Sergeant Maxwell, are you okay, did you get bit or something?" He replied, "your, your pictures are just absolutely amazing, you have captured the very essence, the spirit of what war is. I couldn't do that with my cell phone camera." Being humble is a natural gift to me and giving grace, I replied, "I can show you a way to take your pictures and apply with a little knowledge and give you a spare camera to take your pictures from good to great." He was more than happy to learn and get set up and going on classes with skillshare once he got back to civilian life. It made me feel good that I had mentored someone who wanted to learn the right way and take his pictures to the next level. I didn't mind giving him one of my backup cameras because I knew that either the Army or the insurance company that covers my camera gear would give me the money to get a backup camera.

Sergeant Maxwell left to go and talk to his soldiers. I grabbed my camera and walked around the base until I came upon a team of soldiers digging foxholes and trenches. They were filling sandbags from the sand; they were digging up and building and reinforcing the barrier walls with sandbags. It was quite a team effort. I had backed up twenty feet so that I could get the whole scene in my lens. If there was one thing that I could honestly say about our troops, it was that they all worked as a team. The squad leader told me that they didn't have to do dig and fill sandbags. He and his soldiers wanted to work out, so they took the initiative to do what they could with there e-trenching shovel and dug and filled sandbags for their exercises. Some soldiers were doing pushups, and another set of soldiers were sitting on other soldiers' feet while the other soldier was doing situps. It was good to see that they wanted to stay in top physical shape for whatever comes around the corner.

After I took pictures of some of the troops doing their physical exercises, I came upon a couple of soldiers huddling over a small fire. I asked them what they were doing and if I could take their picture. They responded with sure and opened up their fire pit to me. They had a snake on a spigot and were cooking it. I got done on my knees so that I would be shooting their picture at eye level along with the snake on the spigot that they were turning to cook it evenly.

One of the soldier's names was private first class John Booyah. He was from Louisiana. He told me that almost all snakes taste like chicken and that he would know because of his heritage and roots of living in Lousianna where snakes were as big as small vehicles. He would frequently eat snakes. He took his knife out of his pocket and cut a small piece of the snake off and handed it to me. I took it and put it in my mouth and ate it. John was right; the snake tasted just like chicken. It wasn't too bad. I thought I could sit there with John and his friends and share their spoils of food and camaraderie, but I had a job to do of photo-documenting everything that the soldiers and I were doing over here in Kuwait.

I gnawed on that piece of snake like it was beef jerky. It wasn't that bad. It reminded me of when I was married to my first wife, and she and I went to Florida for our honeymoon, and we had eaten some alligator. That too tasted like chicken, but it was a bit more blubbery, but it did go down well with bud light. Man, thinking about that made me miss having a drink on the porch and watching those beautiful Montana Sunsets. That was one thing about Montana that I missed was those sunsets and the wildlife.

I could sit on my front porch and watch deer and elk and moose come walking right on through my yard. It was amazing watching the animals. That was another reason why I got into photography. I wanted to take pictures of the wildlife. I took pictures of wolves, bears, coyotes, deer, elk, and other forest and mountain wildlife but moose. That was going to be one of my goals when I got back home, and that was to take pictures of some moose.

Another one of my goals was to make it to Africa and go on one of those African tours and take pictures of elephants and zebras, alligators and crocodiles, and wilder beasts. Africa would be a hot zone for wildlife photography. Plus, I had the longest lenses to stay within safety zones without being charged by a rhinoceros or giraffes. I thought to myself, taking pictures of Lions would be pretty cool as well.

Yes, being a photographer has its benefits. You can set your own hours and your going rate and work for yourself and contracting yourself out for side gigs like weddings or engagements. Also, there are so many different avenues for what you can do with a photography license. You can be a real estate photographer, a boudoir photographer, which sounds pretty cool, taking pictures of half-naked beautiful women. There's portraiture photography, astral photography, sport photography, food photography, event photography, or green screen photography. This sounds pretty neat, and if your good at it, you get a Hollywood agent, show them your portfolio, and work as a Hollywood photographer. Some photographers like chasing down A list actors and become the paparazzi. The sky is unlimited with what you can do with photography; just go out there and get a real camera with bigger lenses than a 1.2-megapixel camera on your cell phone and take some lessons.

The End

If you enjoyed this story, then you'll Love an excerpt from my previous book. Tortured Soul.

The sun was shining through the iron-rimmed glass from the basement window that I could tell from the black sackcloth that covered my head; warmed the iron shackles that bound my wrists. The faint smell of mildew from the corners in this basement filled my nostrils until another bucket of water splashed up against my face.

A voice yelled, "Tell me who you're working for"?

I could feel the hairs on my neck and arms stand on end as a surge of electricity flowed through the air as I heard sparks fly. No doubt from the battery cables hooked up to a battery and causing sparks to fly around my head. Suddenly, I could smell through the blood clots through my broken nose, and I could smell the rotten stench of death and decay in this room. I could feel a trickle of blood going down my right thigh, and tears flowing out of my bruised eyes down to my broken jaw. A veil of blackness fell over my eyelids as the last thing that I felt was the dagger being pulled out of my right thigh.

My mind raced back to when I was just a grunt, a mechanic in the Army.

Life was so much simpler and more relaxed. I was working on changing the oil out of an old duece and half Army tactical vehicle. The drain plug was stripped and wasn't coming loose. I thanked God for my trusty mechanic's toolbox and reached for a one-inch closed-end wrench. I attached it to the socket wrench that I was trying to unscrew the drain plug. I gave it a good pull and whooosshhh; I was covered in oil. I hurried and put the drain pan under the oil pan to collect the oil that hadn't already covered me. I crawl out from underneath this old duece and a half and survey the oil mess that covered me and the ground. I make my way back to the motor pool to hear one of my NCO's say, "Keller, I didn't know you were black." We laughed, and I went to clean up and change into another set of mechanic overalls. I went to the pll office and got cat litter, oil, a new drain plug, and an oil filter. I finish replacing the oil and starting this old beast up and pulling it forward so that I can toss the cat litter over the oil and get it cleaned up. As I'm parking the rig back in its original position, I feel a stabbing pain in my left thigh.

My eyes blink so fast that they start to tear up again, and I feel a knife intruding into my left thigh. Even with this black sackcloth over my head, I feel dust intrude into the cloth, and it starts to make me dry heave. My bound ankles and wrists make it hard to control my body, and I can barely bend over to get the dust out of my mouth. The ground was hard underneath my bare feet. I feel a cold hard steel brush up against my feet' then I feel the claw end of a hammer. The only thing that I could think of was that my interrogators were going to break each one of my toes until I gave them some useful information about the Army unit that I was with. I feel the hands of one of the interrogators grab my foot and about to start breaking my toes until a voice says, "That's enough for now."

I feel one of my captors behind me and choke me out till I pass out again.

We were on guard duty guarding a water tower at Fort Carson, Colorado.

Specialist Douglas Mcneil looks at me and says, "who in their right mind would attack a water tower." At this time, I was the E-5 sergeant and explained that our water supply would be ideal. If the enemy wanted to attack a military base. They could poison and take out the whole or part of our military base by taking out our necessities. Specialist Mcneil says, what the hell is that?" We both look up and see a blanket of shooting stars canvas the night sky. I start to think that I see stars inside the cab of our duece and a half. I'm brought back to reality, and I physically see stars of shooting pain circle my head like a cartoon character that has just been whacked with 120 watts of electricity. I can smell the burnt skin of electric burns on my chest. I screamed out in agonizing pain, "Girl Scouts are more torturous than you assholes." I could still flex my toes. They hadn't broken them, Thank God. That would have severely hindered but not impossible to make my escape. Still being chained and shackled and blindfolded, though, I didn't and wasn't sure how I would make my grand escape. Maybe there was a rescue team on there way. But where was I at? Would the Army special forces be coming for me or for the tech package that I was trying to get back into the United States' hands? I was and accepted the fact that I was collateral damage. I knew that when I signed on the dotted line for uncle sam.

The piece of technology that I was sent to get and secure it back at our embassy was cutting edge satellite reconnaissance imagery. It would help our troops in real-time know where by heat signatures where the enemy would be. It would be a game-changer for any country, and anyone would pay billions for this technology.

I feel the interrogators knife slice into my left shin. The pain is almost unbearable, but I still maintain consciousness. I verbally spat out what any soldier should if ever captured and tortured for information. Sergeant Keller Casey J serial code charlie sierra sierra five one eight eight four eight four nine two. A massive fist pounds into my already broken jaw. The pain is intense and throbbing. I feel my teeth being broke, and I spit them out with a mouth full of blood against the black sackcloth. I know this is getting intense, and I can barely contain the information about the technology. The interrogators wanted the code to the case that the tech was in and see if it worked. I thought I had finally had enough. My mind suddenly got flooded with old songs. I start singing. We all live in a yellow submarine and itsy bitsy teeny weeny yellow polka dot bikini. Anything that would keep my mind from breaking. Just as I am about to break out into Roxanne, you don't have to turn your red, and a gruff voice says, "shut him up." I pass out from a stabbing into my appendix, and it is surgically removed. These interrogators obviously knew what they were doing. They knew what hurt and what would kill. The didn't want me dead yet; they needed to get into the case that held billions of dollars of a high tech piece of equipment.

I remember Millie and I's wedding; it was beautiful. Her dress was amazing. I even had a hand in sewing some of the sequins on her dress. My groomsmen Tyler, Shadd, and Kirk, were handsome in their tuxedos. Kimberly Kerri, and Trina, Millie's bridesmaids were beautiful in their emerald green dresses; Mathew, my godson, was the ring bearer. Families filled both sides of the church. The wedding song comes on, and Millie comes down the aisle with my dad in tow to give her away because her father had passed away. With Mathew in tow with the rings, my father says his line that he is giving away the bride and seats himself.

Mathew stands behind kirk. Millie joins me at the altar, and in that one moment, everything stood still, and it seemed like it was just her and I at that moment. Our eyes teared up, and with one gentle hand, I reach up and wipe away one of her tears rolling down her face. It was that one pivotal moment that made everyone else in that church well up with emotion. Remembering that moment jarred me awake at the feeling of being sewn up. I presumed it was a doctor that was sewing up where my appendix was once at.

It was as if my memories were being stimulated by what my interrogators were doing to my body. It would be my death before I broke down and told them what they wanted to know. I feel the needle and thread sewing up my other wounds on my left shin and my right thigh. Without being on any pain medication, antiseptics, and antibiotics, I almost knew beyond the shadow of a doubt that I will have severe health problems. Especially not being in a clean and sterile hospital room. My head is aching, and I would feel like I would die for a couple of Tylenol to ease my body's pain. I would give my left arm to have another bucket of water splashed in my face. I hear a tiny nerdy sounding voice asks, "has he given you the code yet?" It was a voice I thought I had heard before, but I can't place it. Another voice says, "Let's break all of his fingers. He'll talk."

Great, I'm going to be an invalid veteran if I ever get out of here. I feel the cold steel of the hammer again against the skin of my hands. I mentally prepare myself for the breaking of my fingers. Whack, whack, whack, but my fingers are feeling fine, then the throbbing comes in, and my hands hurt, and I pass out from the pain.

It was the middle of a monsoon season in Korea at Camp Humphreys.

"Graeff, let's go have a smoke," I tell the pll clerk. He and I were best buds, always had each other's backs. He and I were also probably the craziest. We put on our ponchos and head out towards the gate that led into the motor pool. He and I were the only idiots in the middle of monsoon by the motor pool gates and smoking our cigarettes. I flex my fingers and try to make fists, and I can't.

Kevin asks me, "Keller, what's wrong with you? Just relax, we're only over here for a couple more months," as I light up another cigarette. My fingers are aching and start swelling as I put out my second cigarette. We head back into the motor pool, and Kevin hands me a new pll request to pull out an alternator and replace it. I take the new alternator out with me and a creeper and the few tools that I know that I'll need. It had to be done; it was the commander's vehicle.

I felt like I was swimming. The monsoon's water was over my chest as I wrenched the old bolts out, moved the belt aside, and the alternator fell out on my chest. I wheel the creeper over to the humvee's door, grab the new alternator, and put the new one in. By the time I was done, I was soaked and had a burning sensation on my chest. I open up my soaked coveralls and pull up my shirt to see cigarette burns all over my chest. I freak out and wake up to the feeling of cigarettes being put out on my chest.

Other than not actually being tortured and not being a war photo-journalist, everything that I have written is true.

Casey J. Keller

About the Creator

Casey Keller

Hi, I'm a 47 year-old-veteran/photographer/door dash driver/uber driver as well. When I am not doing any of those things I can be found sitting in front of my computer writing books for amazon/vocal. keep your mind busy the body stays young

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.