The Volcano Rumbles Before it Erupts

The Causes of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (lasting from June of 1812 to February of 1815) was a conflict which acted as a “Second War of Independence” to signify the lasting power of this upstart constitutional republic known as the United States, and the last war which the US would engage with the military power of Great Britain. Yet, it is also a war for which little of it is remembered by modern generations of Americans or even people who live across the pond. To many Britons, 1812 was the year of Napoleon’s failed Russia Campaign. Though the war is still remembered by many native tribes and Canadians. To them, this war was their chance to walk into the spotlight and defend their own versions of freedom, liberty, and sovereignty; even if their efforts would result in accidental victory or honorable defeat. Yet, people still wonder how this atmosphere of nationalistic violence came to be. What were the events which transpired that caused the final war between the US and Great Britain? Who were the figures who stirred the political pot too fast or two hard, until the hot water spilled all over the place? This essay seeks to answer such questions and observes the positions of all sides who would find themselves at each other’s throats with muskets, swords, cannons, and scalping knives.

To understand the causes of the War of 1812 and the sides for which this conflict would be composed of, one must fully understand another conflict which was occurring in Europe. From 1796 to 1812, Napoleon Bonaparte proceeded to conquer the European continent from as far west as Spain to as far west as Poland and Austria. From as far south as Italy to the far north of Denmark and Norway. Britain and it’s allies Portugal and Russia would wage war against him in order to preserve their stakes as sovereign powers. Great Britain’s land-based military was nothing in comparison to Napoleon’s “Grand Arme” of 700,000 soldiers, yet their extensive navy was successfully able to cripple supply lines and trade routes from allies of France, ever since Admiral Lord Viscount Horatio Nelson’s victory against Vice Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, at the Battle of Trafalgar, in 1805. During this time, the United States refused to side with France nor with Great Britain or any of their allies, and proceeded to neutrally conduct trade with both imperial entities. That way, the opportunity to make money off of both sides would be a beneficial factor for the growth of such a young nation.

This stance of neutrality would be where the first signs of an international issue would take place. The United Kingdom never recognized America’s intentions of remaining neutral. In their eyes, trading with the enemy meant siding with them and that you are consequentially vulnerable to the might of the Royal Navy. By 1807, English Parliament decreed legislation that would undermine American shipping. All ships which have declared neutrality and were willing to trade with the French Empire would have to mandatorily stop at a British port and pay a duty. If a ship refused to pay or dock at a port, they would be subject to British cannon fire and boarding. Hundreds of American merchant vessels and navy ships would be attacked and between 6,000 and 15,000 American sailors would be subject to impressment by British captains to mandatorily serve Royal Navy ships at gunpoint.

The most notorious case of impressment was the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, in which four sailors were removed from a U.S. naval vessel in June, 1807. The resulting tumult nearly caused war with Britain five years earlier than its actual occurrence. The British government disavowed the actions of the HMS Leopard, ordered the complete cessation of waylaying American naval ships, and subsequently had the Royal Navy excise greater care in searching U.S. merchant vessels. Yet the return of two of the USS Chesapeake sailors (of of the four was a Briton who was executed for desertion, and the other, an American who died in a Halifax hospital) was delayed until 1811, thus reviving the 1807 incident and reanimating the impressment debate in such a way as to have it figure prominently as a spur towards war. (Heidler 282)

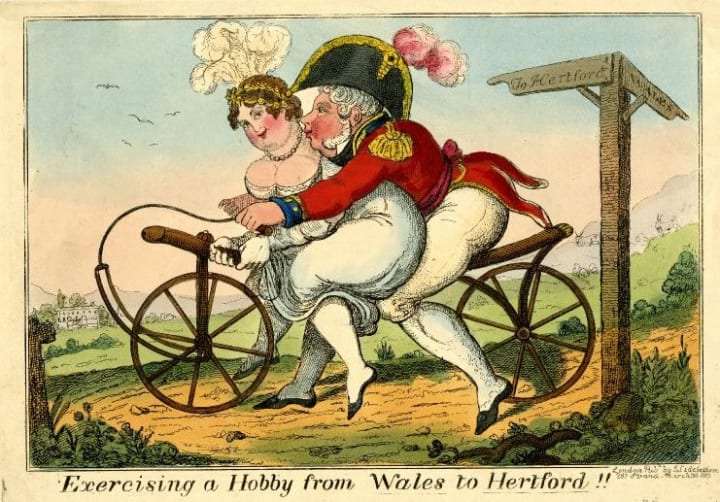

In the eyes of the English, these actions were a justifiable means of keeping the economic power of France at bay and bringing in a steady supply of sailors; with the competition of privateering vessels and the Royal Merchant Marine. After all this practice was being done since the time of Queen Elizabeth I, in 1563. Though by 1807, the practice was recognized as a cruel and unpopular one. Since sailors in international waters were not protected by the Magna Carta or the stipulations of the English Constitution, acts of resistance could result in instant execution by the hand of the captain. To the Americans, the impressments of their sailors by the Royal Navy was a relentless series of insults and aggressions, on the high seas, to a second rate, neutral, power. No war would be declared in 1807, but the impressments would be a significant step in the directions towards war. A war which would only be another piece of bad news for Great Britain, alongside the threat of conquest by Napoleon, the deteriorating sanity of King George III, and Prince Regent’s (future King George IV) failure to abide by his statesman duties; preferring instead to drink and feast to his heart's content (gaining a stonking weight of 330 pounds), as well as revel in his sexual pleasures with numerous ladies of ill repute.

By 1810 and 1811, a new generation of political entities would begin to make its mark in Washington D.C., such as the Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun, and Tennessee Congressmen Felix Grundy. These men would begin to address their grievances towards England’s acts of impressment and excessive duties and encourage what they viewed as appropriate measures to remove their power and influence from the North American Continent. Even if the solution to removing British influence from North America was by means of war.

It is said...that no object is attainable by war with Great Britain. In its fortunes, we are to estimate not only benefit to be derived to ourselves, but the injury to be done the enemy. The Conquest of Canada is in your power. I believe that the militia of Kentucky is alone competent to place Montreal an Upper Canada at your feet. Is it nothing to the British nation; is it nothing to the pride of her Monarch, to have the last of the immense North American possessions held by him in the commencement of his reign wrested from dominion? Is it nothing to us to extinguish the torch that lights up savage warfare? Is it nothing to acquire the entire fur trade connected with that country and to destroy the temptation on and the opportunity of violating your revenue and other laws? (Annals of congress, 11th congress, 1st Session (1810). 580)

The true question on in controversy... involves the interest of the whole nation. It is the right of exporting the production of our own soil and industry to foreign markets. Sir, our vessels are now captured... and condemned by the British courts... without even the pretext of having on board contraband of war. The United States are already the second commercial nation in the world. The rapid growth of our commercial importance has... awakened the jealousy of the commercial interest of Great Britain, ... her statesmen, no doubt, anticipate with deep concern (our) maritime greatness...What, Mr. speaker, are we now called on to decide? It is whether we will resist by force the attempt... to subject our maritime rights to the arbitrary and capricious rule of her will. For my part I am not prepared to say this country shall submit to have the commerce... regulated, by any foreign nation. Sir, I prefer war to submission. (Annals of Congress, 12th Congress, 1st Session (1811), I, 424)

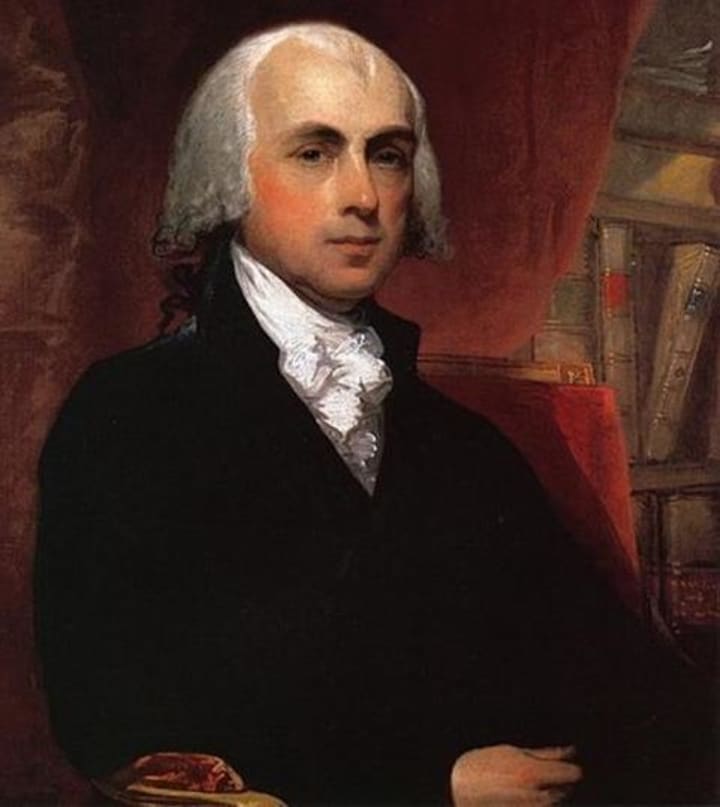

Such politicians were part of a group of “First Generation Americans” which arose from the era of the original founders of the country (John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, etc.). However, what was defined as reasonable and politically sensible by the Founding Fathers would often be interpreted as politically intolerable by these indigenous-born Americans; also known as “War Hawks”; a select branch of Jeffersonian Republicans, which would rattle the political cage against the Federalist Party and the likes of future president James Madison. However, this was also at a time when Thomas Jefferson and his presidential cabinet had severely downsized the military in terms of economic funding and power; leaving the standing force of the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy would be no bigger than 8,000 infantry and 30 ships, as well as a series of officers who once served well in the American Revolution, but had long since grown elderly and incompetent. The solution to such a small standing federal force would be to strengthen the use of state/territorial militias and privateers (pirates with government permission to engage the enemy at sea). The downside to this plan is that the militias were poorly funded and regulated. Depending on which state or territory the militias came from, they often had no standard uniforms, their officers were democratically elected by their fellow comrades, their weapons were supplied by the individual militiamen (often consisting of aged muskets, small caliber hunting rifles, and mele weapons such as throwing axes and knives), and their training lacked the sufficient discipline worthy of engaging a European imperial force, capable of thousands of hardcore soldiers, ships of the line, and first rate weaponry.

Yet, it is not just the eradication of British power in North America that these War Hawks desired. Many of them were dedicated expansionists and sought to civilize the frontier territories to the west and the land referred to as Upper Canada; such land was still heavily occupied by native tribes (Chickasaw, Potawatomi, Chippewa, Miami, Choctaw, Creek, and Shawnee nations to name a few). Some of these indigenous nations were willing to sell their ancestral lands to the U.S. after years of clashes with frontier villagers and army garrisons (such as the Harmar Campaign of 1790, the Battle of the Wabash in 1791, and the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794), but one Shawnee chief and his shaman brother intended to stir resistance at all costs. Their names were Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa. Both of them were respected warriors and survived many instances of bloodshed between their fellow tribesmen and American soldiers (Tenskwatawa himself had lost sight in one of his eyes from a battle wound); and because of their witnessing of such heavy losses to their nation, it resulted in a shared belief that the only way to survive is to constantly resist U.S. encroachment on what was rightfully theirs, but also to reinforce their existence and power by uniting all the tribes together into one confederation (much like how the individual thirteen colonies depended on sense of unity to identify themselves a solitary power against a distant oppressor).

Brothers,—We all belong to one family; we are all children of the Great Spirit; we walk in the same path; slake our thirst at the same spring; and now affairs of the greatest concern lead us to smoke the pipe around the same council fire!

Brothers,—We are friends; we must assist each other to bear our burdens. The blood of many of our fathers and brothers has run like water on the ground, to satisfy the avarice of the white men. We, ourselves, are threatened with a great evil; nothing will pacify them but the destruction of all the red men. Brothers,—When the white men first set foot on our grounds, they were hungry; they had no place on which to spread their blankets, or to kindle their fires. They were feeble; they could do nothing for themselves. Our father commiserated their distress, and shared freely with them whatever the Great Spirit had given his red children. They gave them food when hungry, medicine when sick, spread skins for them to sleep on, and gave them grounds, that they might hunt and raise corn.

Brothers,—The white men want more than our hunting grounds; they wish to kill our warriors; they would even kill our old men, women and little ones. Brothers,—Many winters ago, there was no land; the sun did not rise and set: all was darkness. The Great Spirit made all things. He gave the white people a home beyond the great waters. He supplied these grounds with game, and gave them to his red children; and he gave them strength and courage to defend them.

Brothers,—My people are brave and numerous; but the white people are too strong for them alone. I wish you to take up the tomahawk with them. If we all unite, we will cause the rivers to stain the great waters with their blood. Brothers,—If you do not unite with us, they will first destroy us, and then you will fall an easy prey to them. They have destroyed many nations of red men because they were not united, because they were not friends to each other. Brothers,—Who are the white people that we should fear them? They cannot run fast, and are good marks to shoot at: they are only men; our fathers have killed many of them; we are not squaws, and we will stain the earth red with blood. Brothers,—The Great Spirit is angry with our enemies; he speaks in thunder, and the earth swallows up villages, and drinks up the Mississippi. The great waters will cover their lowlands; their corn cannot grow, and the Great Spirit will sweep those who escape to the hills from the earth with his terrible breach. Brothers,—We must be united; we must smoke the same pipe; we must fight each other's battles; and more than all, we must love the Great Spirits he is for us; he will destroy our enemies, and make all his red children happy. (historyisaweapon.com)

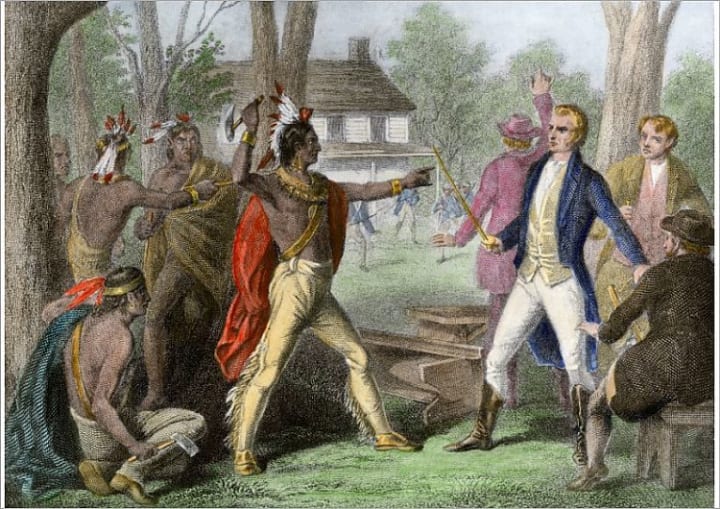

In August of 1810, Tecumseh attempted to negotiate terms with Indiana’s territorial governor, William Henry Harrison (a veteran of the Battle of Fallen Timbers). They arranged to meet outside Harrison’s estate at Vincennes, Indiana Territory. On the date of the gathering, Tecumseh arrived with his brother Tenskwatawa and an assortment of armed warriors. For the sake of the governor’s protection, a detachment of federal troops were sent to this gathering ahead of time. When Governor Harrison insisted that he and Tecumseh proceed with their negotiations for peace inside his home, Tecumseh delivered the following speech before the crowds outside.

Houses are built for you to hold councils in. Indians hold theirs in the open air. I am a Shawnee. My forefathers were warriors. Their son is a warrior. From them I take my only existence. From my tribe I take nothing. I have made myself what I am. And I would that I could make the red people as great as the conceptions of my own mind, when I think of the Great Spirit that rules over us all. I would not then come to Governor Harrison to ask him to tear up the treaty. But I would say to him, "Brother, you have the liberty to return to your own country." You wish to prevent the Indians from doing as we wish them, to unite and let them consider their lands as a common property of the whole. You take the tribes aside and advise them not to come into this measure. You want by your distinctions of Indian tribes, in allotting to each a particular, to make them war with each other. You never see an Indian endeavor to make the white people do this. You are continually driving the red people, when at last you will drive them into the great lake where they can neither stand nor work. Since my residence at Tippecanoe, we have endeavored to level all distinctions, to destroy village chiefs, by whom all mischiefs are done. It is they who sell their land to the Americans. Brother, this land that was sold, and the goods that was given for it, was only done by a few. In the future we are prepared to punish those who propose to sell land to the Americans. If you continue to purchase them, it will make war among the different tribes, and, at last I do not know what will be the consequences among the white people. The way, the only way to stop this evil, is for the red people to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was at first, and should be now -- for it was never divided, but belongs to all. No tribe has the right to sell, even to each other, much less to strangers. Sell a country?! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children? How can we have confidence in the white people? We have good and just reasons to believe we have ample grounds to accuse the Americans of injustice, especially when such great acts of injustice have been committed by them upon our race, of which they seem to have no manner of regard, or even to reflect. When Jesus Christ came upon the earth you killed him and nailed him to the cross. You thought he was dead, and you were mistaken. You have the Shakers among you, and you laugh and make light of their worship. Everything I have told you is the truth. The Great Spirit has inspired me. (americanrhetoric.com)

It was at this moment where Governor Harrison publicly denounced Tecumseh’s words and accused him and his fellow Shawnees of conquering the lands of neighboring tribes prior to his campaign of Indian unity; labeling him as a windbag hypocrite. It was at this moment where Tecumseh angrily drew his tomahawk and Harrison drew his sword. The warriors and federal troops primed their weapons. The crowds of civilians witnessing this watched in fear of a massacre. Ultimately, both Tecumseh and Harrison backed down and ended their meeting on such a note. It would be the last time when both of these figures would meet on sociable terms.

By November of 1811, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa had gathered a unified force of nearly 5,000 warriors and established their base of operations at Prophetstown (what is now Tippecanoe, Indiana). Since his hostile encounter with Tecumseh, Governor Harrison sought to quickly undermine this rising insurgency and gathered a force of over 1,000 federal troops and territorial militiamen to march on Prophetstown, at a time when Tecumseh would be away from the village to recruit other tribes. As Harrison’s force set up camp along the Tippecanoe River, Tenskwatawa has awoken from a deep sleep and vision of a native victory; warriors charging out of the woods, slaughtering the Americans and their commander, Harrison as they slept. He defied the orders of his brother to maintain the peace at all costs and ordered a force of 700 warriors to attack the garrison in the dead of night. Tenskawata’s vision couldn’t be any further from what was about to transpire.

Early on the morning of November 7, the Indians from Prophetstown attacked the US encampment, expecting that the Prophet’s special powers would enable them overcome the Americans. The battle was fiercely fought, and the Americans lost nearly 200 killed and wounded. It was likely that Indian casualties were about the same. Harrison, however, claimed a major victory because the Indians dispersed; Prophetstown was deserted; and after seizing food supplies, Harrison’s troops burned the village. (Heidler 515)

Furthermore, the discovery of hundreds of of Baker Rifles and Brown Bess Muskets (British manufactured firearms) during the destruction of Prophetstown lead to the discovery of agents from Canada delivering these weapons from British garrisons to Prophetstown and other native villages under Techumseh’s influence. From the British perspective, the idea of a united indian nation could act as an appropriate buffer zone between the United States and colonial territories in Canada. With these actions of impressment and inspiration of Indian insurgency in mind, President Madison would deliver a request to declare war in June of 1812.

I communicate to Congress certain documents, being a continuation of those heretofore laid before them on the subject of our affairs with Great Britain. ... Without going back beyond the renewal in 1803 of the war in which Great Britain is engaged, and omitting unrepaired wrongs of inferior magnitude, the conduct of her government presents a series of acts hostile to the United States as an independent and neutral nation. ... British cruisers have been in the continued practice of violating the American flag on the great highway of nations, and of seizing and carrying off persons sailing under it, not in the exercise of a belligerent right founded on the law of nations against an enemy, but of a municipal prerogative over British subjects. British jurisdiction is thus extended to neutral vessels in a situation where no laws can operate but the law of nations and the laws of the country to which the vessels belong, and a self-redress is assumed which, if British subjects were wrongfully detained and alone concerned, is that substitution of force for a resort to the responsible sovereign which falls within the definition of war. Could the seizure of British subjects in such cases be regarded as within the exercise of a belligerent right, the acknowledged laws of war, which forbid an article of captured property to be adjudged without a regular investigation before a competent tribunal, would imperiously demand the fairest trial where the sacred rights of persons were at issue. In place of such a trial these rights are subjected to the will of every petty commander. ... The practice, hence, is so far from affecting British subjects alone that, under the pretext of searching for these, thousands of American citizens, under the safeguard of public law and of their national flag, have been torn from their country and from everything dear to them; have been dragged on board ships of war of a foreign nation and exposed, under the severities of their discipline, to be exiled to the most distant and deadly climes, to risk their lives in the battles of their oppressors, and to be the melancholy instruments of taking away those of their own brethren. ... British cruisers have been in the practice also of violating the rights and the peace of our coasts. They hover over and harass our entering and departing commerce. To the most insulting pretensions they have added the most lawless proceedings in our very harbors, and have wantonly spilt American blood within the sanctuary of our territorial jurisdiction. The principles and rules enforced by that nation, when a neutral nation, against armed vessels of belligerents hovering near her coasts and disturbing her commerce are well known. When called on, nevertheless, by the United States to punish the greater offenses committed by her own vessels, her government has bestowed on their commanders additional marks of honor and confidence. … To our remonstrances against the complicated and transcendent injustice of this innovation the first reply was that the orders were reluctantly adopted by Great Britain as a necessary retaliation on decrees of her enemy proclaiming a general blockade of the British Isles at a time when the naval force of that enemy dared not issue from his own ports. She was reminded without effect that her own prior blockades, unsupported by an adequate naval force actually applied and continued, were a bar to this plea; that executed edicts against millions of our property could not be retaliation on edicts confessedly impossible to be executed; that retaliation, to be just, should fall on the party setting the guilty example, not on an innocent party which was not even chargeable with an acquiescence in it. ... When deprived of this flimsy veil for a prohibition of our trade with her enemy by the repeal of his prohibition of our trade with Great Britain, her cabinet, instead of a corresponding repeal or a practical discontinuance of its orders, formally avowed a determination to persist in them against the United States until the markets of her enemy should be laid open to British products, thus asserting an obligation on a neutral power to require one belligerent to encourage by its internal regulations the trade of another belligerent, contradicting her own practice toward all nations, in peace as well as in war, and betraying the insincerity of those professions which inculcated a belief that, having resorted to her orders with regret, she was anxious to find an occasion for putting an end to them. ... It has become, indeed, sufficiently certain that the commerce of the United States is to be sacrificed, not as interfering with the belligerent rights of Great Britain; not as supplying the wants of her enemies, which she herself supplies; but as interfering with the monopoly which she covets for her own commerce and navigation. She carries on a war against the lawful commerce of a friend that she may the better carry on a commerce with an enemy ? a commerce polluted by the forgeries and perjuries which are for the most part the only passports by which it can succeed. ... There was a period when a favorable change in the policy of the British cabinet was justly considered as established. The minister plenipotentiary of His Britannic Majesty here proposed an adjustment of the differences more immediately endangering the harmony of the two countries. The proposition was accepted with the promptitude and cordiality corresponding with the invariable professions of this government. A foundation appeared to be laid for a sincere and lasting reconciliation. The prospect, however, quickly vanished. The whole proceeding was disavowed by the British government without any explanations which could at that time repress the belief that the disavowal proceeded from a spirit of hostility to the commercial rights and prosperity of the United States; and it has since come into proof that at the very moment when the public minister was holding the language of friendship and inspiring confidence in the sincerity of the negotiation with which he was charged a secret agent of his government was employed in intrigues having for their object a subversion of our government and a dismemberment of our happy union. ... In reviewing the conduct of Great Britain toward the United States our attention is necessarily drawn to the warfare just renewed by the savages on one of our extensive frontiers? A warfare which is known to spare neither age nor sex and to be distinguished by features peculiarly shocking to humanity. It is difficult to account for the activity and combinations which have for some time been developing themselves among tribes in constant intercourse with British traders and garrisons without connecting their hostility with that influence and without recollecting the authenticated examples of such interpositions heretofore furnished by the officers and agents of that government. ... Whether the United States shall continue passive under these progressive usurpations and these accumulating wrongs, or, opposing force to force in defense of their national rights, shall commit a just cause into the hands of the Almighty Disposer of Events, avoiding all connections which might entangle it in the contest or views of other powers, and preserving a constant readiness to concur in an honorable re-establishment of peace and friendship, is a solemn question which the Constitution wisely confides to the legislative department of the government. In recommending it to their early deliberations I am happy in the assurance that the decision will be worthy the enlightened and patriotic councils of a virtuous, a free, and a powerful nation. (Hickey 1-8)

And so would begin a secondary war for the security of American sovereignty, fueled by these actions of international maritime impressment and equipment of discontented native warriors on the American frontier. By the conflict’s end in 1815, Britain would keep their colonial holdings in Canada, the United States would expand into new horizons with conquered Indian lands and newly formed states in the Northwest and the South, and the native tribes which once resided peacefully on their former grounds would lose the ability to self-govern themselves as people; referring to the “great chief in Washington” then and now in the course of over 200 years.

Works Cited

- Hickey, Donald. The War of 1812: Writings from America’s Second War of Independence. Literary Classics of the United States, 2013. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Heidler, David. Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. ABC-CILO Inc., 1997. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Black, Jeremy. The War of 1812 in the Age of Napoleon. University of Oklahoma Press, 2009. Print Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Horsman, Reginald. The Causes of the War of 1812. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1962. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Perkins, Bradford. The Causes of the War of 1812: National Honor or National Interest?. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston Inc, 1962. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Perkins, Bradford. Prologue to War: England and the United States. 1805-1812. University of California Press, 1961. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Sugden, John. Tecumseh: A Life. Henry Holt and Company, 1997. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Tucker, Glenn. Tecumseh: Vision of Glory. The Bobbs-Merril Company Inc., 1956. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

- Edmunds, David, R. Tecumseh and the Quest for Indian Leadership. Little, Brown, and Company, 1984. Print. Accessed May 2, 2020.

About the Creator

Jacob Herr

Born & raised in the American heartland, Jacob Herr graduated from Butler University with a dual degree in theatre & history. He is a rough, tumble, and humble artist, known to write about a little bit of everything.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.