My dad passed away a few years ago, but if you’d had met him, you’d have not thought that he was very threatening. Even in his later years, he still had a full head of dark hair sprinkled with grays. He was still handsome with a charming lopsided grin that had caused my mom a lot of stress in their younger years. He was quite the talker, after all. Time and genetics had been kind to his face despite the fact that he’d been a farmer for the last 30 years of his life, more or less. Even as cancer took its toll on him in the last few months of his life, it was still evident that my dad had been a heartbreaker in his youth. He’d shrunk a bit in the last few years, standing at barely 5' 3". Or maybe I’d had just grown taller in my adulthood and remembered him as taller from my youth. I’m sure it’s a mix of the two.

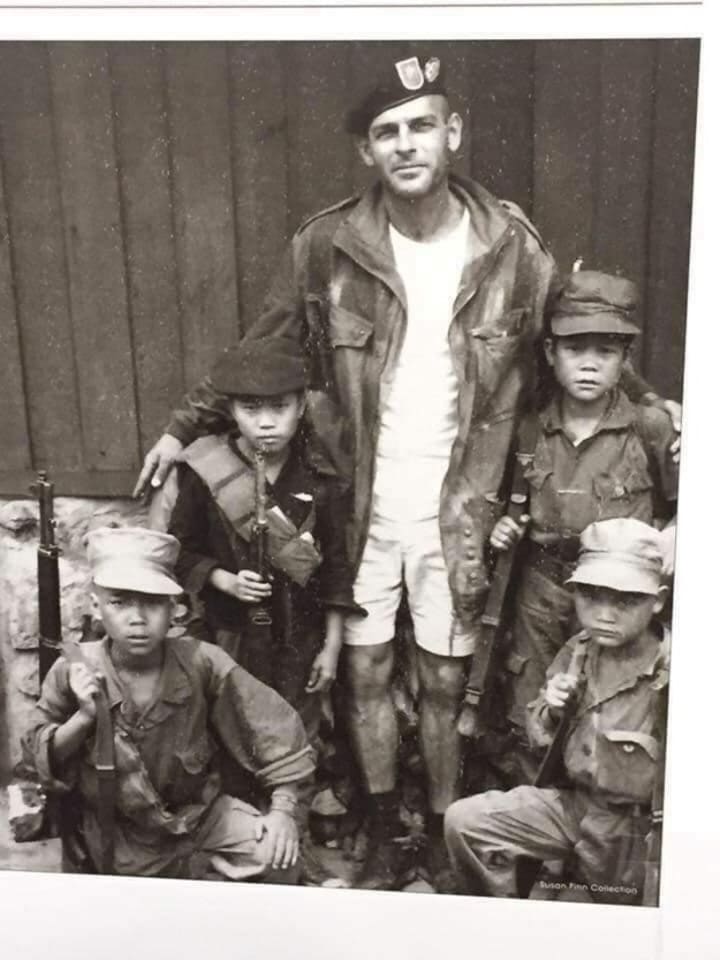

When my dad was twelve, a call came over the village CB radio from the American command post. Too many Hmong men had died. About 16,000 in a span of two years. Any boy who was big enough to hold a gun would need to be recruited to fight. At least one son from each family would need to go.

As it were, many were already doing night patrols of their hilltop villages, sitting in the deep trenches that had been dug around the perimeters of the cluster of little wooden houses. At the slightest noise in the pitch black, those small boys would muster up what courage they had and slide into the thick brush of the jungle with their guns held in steady hands. They had to make sure that the noise was just the wind and not the Pathet Lao soldiers looking to ambush their homes. Many of those boys would disappear into the darkness and never return.

This was the Secret War, a clandestine CIA operation in the jungles of Laos that ran from 1961 to 1975. Even before the official start of the Vietnam War and American soldiers touching ground in Vietnam, the Hmong had already been recruited to be guerrilla fighters for America. Their primary jobs were to disrupt supply lines for the communist Pathet Lao that would eventually feed into the Viet Cong in Vietnam and to rescue downed American pilots that fell behind enemy lines. It’s said that for every one American saved, ten Hmong soldiers died in the rescue effort.

My grandfather was already a medic in the army, and my eldest uncle was away at school, so as the second son, my grandparents chose my dad to go. When the tall, white soldier came to their village, my dad was just a boy. For the next ten years, my dad would spend his adolescence and young adulthood leading his band of brothers over fields of broken and rotting bodies, dodging landmines, and lying in wait in the thick of the jungle. He’d grow up in the shadows of death.

He never spoke about the war in detail. At least, not with me and my siblings. I never got the chance to ask him when he made his first kill. I just know that he did. In my childhood, mentions of the war would either elicit rage or a sort of lost quietness that would choke him up and make his lips purse. Sometimes, I’d catch moments of wistfulness in his eyes as he’d stare off into the distance, remembering.

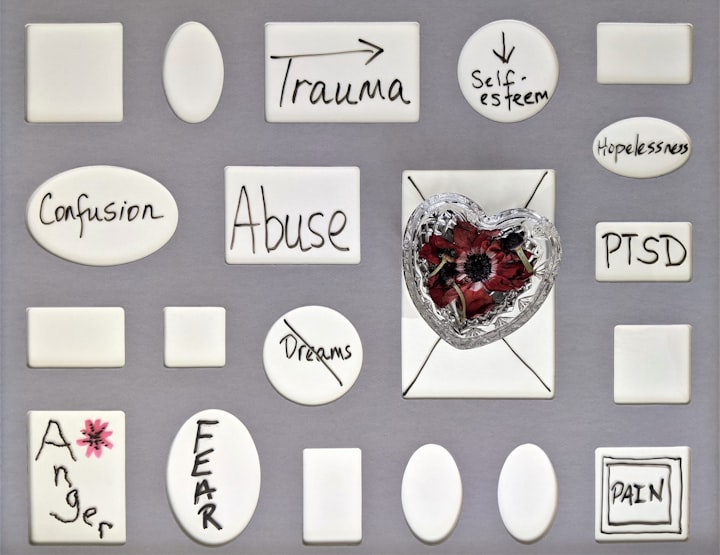

In those first few years when we’d been resettled into America, there were many nights where he’d wake up in a sweat and the following day, he’d be in an inexplicable rage. He’d lash out at everyone in the house. His demands and expectations for military precision and obedience would catch me and my older brother off guard. My mother would often bear the brunt of his anger. It’s still hard to remember all of the details from my childhood as I’d subconsciously suppressed them. I just remember being small and scared of him. I just remember flinching to his touch and hiding under my bed.

It wasn’t until adulthood that I learned about PTSD.

In hindsight, I now understood why he sought out the company of his fellow soldiers. They understood. He could talk about the war with them. He could tell them things and remember what he couldn’t even speak about with his own brothers.

I remember one bright yellow California summer day. I was fourteen. The sun was scorching and the dust from our small farm was blowing loose across the rows of cherry tomatoes. My dad was standing next to the irrigation ditch with what I was told then was an uncle, but I’d learn much later that the man had actually been one of my dad’s soldiers. He’d fought under my dad’s command.

At first, their conversation was about some upcoming family event, about who was doing what, and the reasons for the event. I’d been tasked by my mom to go fetch my dad for lunch.

“It’s so hot today,” the uncle said, pulling his straw hat lower across his brow. “Do you remember how hot it was in the brush?”

“Oh yo,” my dad responds, “At least it’s not humid.”

“You’re right. At least it’s not humid. If it were, it’d be like the night we killed those Lao soldiers.” The uncle had said it in such a nonchalant manner, but for me, it was the first time I realized that my dad had killed people.

It wouldn’t be until my dad was dying that I’d see that uncle again or hear more of my dad’s war stories as told by the surviving soldiers who’d come to pay their last respects. They’d waited all this time — some forty years later — before they came to share their memories of him.

He was courageous, they said. Young, but brave. He’d commanded with a steel backbone. Though they were all unofficial and would never be able to claim their roles or claim any VA benefits, they’d fought for America. They’d killed for America. So many of their brothers had died for America.

“Your dad saved so many of us,” one uncle says to me. “He always led the charge.”

One of my great-uncles had been dad’s commanding officer and several of dad’s cousins had fought alongside him. It was a kind of brotherhood that my immediate uncles — his brothers — would never know nor could they ever appreciate. Even now, I don’t think his brothers understood the weight of my dad’s sacrifice. Because of him, they got to go to school. Because of him, they never had to know what it meant to take a life.

“We were on patrol,” says a distant uncle as he sat next to my dad’s still body. A hospital bed had been set up in our living room. At this point, dad was already unconscious and the hospice care only supplied him with morphine to ease his pain. Dad’s chest rose and fell as he gasped for air like the hiccuping of a fish.

“The jungle was full of bodies,” the uncle continued, “At night, you sometimes think you’re walking in mud, but it was blood. We were on our way back to the base, but we got ambushed. The Pathet Lao were waiting for us and they started shooting. Your dad’s cousins were in front of him and were the first ones hit. Your dad watched his cousins fall to the ground and die. He was so angry, he started screaming and shooting. He killed all those Lao soldiers.

“When they were all dead, we had to hold him back. I was so scared because I had never seen anyone so angry. He took his knife out. He wanted to go cut off the ears of the Lao soldiers and take them back to the American captain and throw them at his feet. He wanted the American to see.”

This would be the first of many more war stories that would emerge. It would be a matter of a day, maybe a few hours before he’d pass. The house was busy with activity as relatives, family friends, and old acquaintances came to say their last goodbyes and to hold vigil with my mom and my family. In between the breaks in sobbing would be stories to fill in the silence. Late into the night, the elders would talk about my dad as a young man, about how he’d helped them cross the Mekong River to Thailand where some measure of safety could be found, or how he’d led them through jungles to villages and refugee camps.

My dad had never had a choice in whether he’d serve or not. Grown men had made that decision for him. Killing had been a necessity, a measure for survival. They’d put a gun into a kid’s hands and forced him into adulthood, into trauma. As an adult now, I’m at an age where I’m able to see my parents as people, to reflect on their lives beyond the eyes and understanding of a child. I can understand now what demons followed them and haunted them in the dark of night.

The war had damaged my dad’s hearing, and all through his life here in America, he’d battle the healthcare system for disability benefits. He’d be continually denied because he “wasn’t deaf enough.” But his ears weren’t the worst damage from the war. His heart and his head suffered much more. I wish America had offered my dad counseling for his PTSD. I wish there had been counseling for all of the Hmong of my dad’s generation, for everyone who survived the Secret War. It’d have saved so many families so much pain.

Or perhaps if America had not thought to use indigenous hill people for their foreign covert operations, half of the Hmong population in Laos wouldn’t have died by 1975. Regardless, we can’t change the past now. What’s done is done. The only thing left to do is to make sure my dad’s legacy lives on, that the stories of these boy soldiers are told, and to move forward to ensure that another group of minorities aren’t manipulated and used for a war that wasn’t of their own making.

My dad became a killer because of America. He fought in a war that left him broken. He fought for a country that will never recognize him. He had no choice, but I do. I have the choice to not be silent and to make sure that all he’d done was not in vain. That all the sacrifices of my people were not in vain. That all that we’d survived makes it into the history books and that our future generations will know where they came from and the high price that was paid for their safety.

The sun is peeking through my window now. The first pink fingers of the dawn are slowly creeping through the blinds to wash my room in shades of gray-blue. I’m back in California, not so far away from where I’d first overheard that long-ago conversation. Somewhere beyond the realm of the living, my dad is with my grandparents, their spirits in the land of my ancestors waiting to be reborn; and I hope for him that in the next life, he’ll be born into a world with no war, into a world where he won’t be forced to kill, into a world where his demons can no longer follow him. I hope for him a chance at the peace that he was never given in this lifetime.

About the Creator

Nev Ocean

Fantasy, romance, fiction author.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.