Love at War: The Sacred Band of Thebes

A concise history of a queer crack military unit of ancient times.

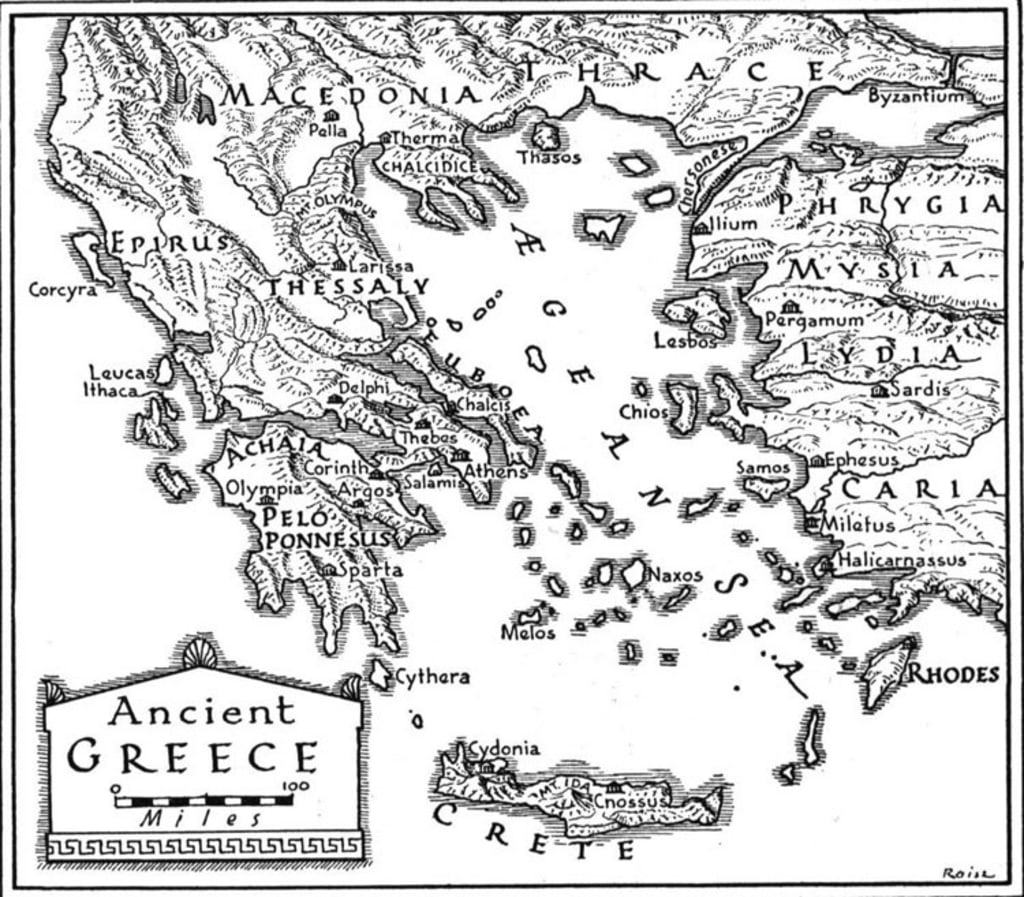

Thebes. The city founded by Cadmus, the land where men sprouted out of dragon teeth sown in the soil. The birthplace of Hercules, Dionysius, and Oedipus. One of the oldest city-states to be established, it rivalled in power and population with her other sister city-states, Athens and Sparta.

Situated on elevated terrain and adorned by a Mycenean-era acropolis named Cadmea, Thebes looked over the plains of Boeotia. Thebes lacked natural harbours like Athens but boasted of fertile lands, bountiful harvests, and excellent cavalry. Backed by a large militia, Thebes was strong enough to hold on her own against other city-states.

Geopolitics and the Corinthian War

Thebes was part of the Boeotian Confederacy, a collection of city-states in the Boeotian plains. Each city-state had a vote proportional to their contribution to the Boeotian army. In reality, it was Thebes calling the shots, becoming the de-facto leader of the federation.

Alliances in Ancient Greece were fickle, states changing sides at the drop of a hat. Thebes was no exception. In the late 6th century BC, we see Thebes in hostile contact with Athens. Thebes then betrayed the entirety of the Greek world in the early 5th century BC by siding with the Persians, which led to it being forced to step down from the Boeotian presidency after the Persians were defeated.

In 457 BC, fearing the rising power of Athens, Sparta reinstated Thebes as the predominant power in Central Greece and declared it a staunch ally in the Peloponnesian War. But when Thebes found the victory terms set by Sparta unfavourable, they broke off the alliance and secretly helped out the war-torn Athens, the very city they swore to destroy.

With the rejuvenated Athens and Persian backing, Thebes formed the anti-Sparta alliance in the Corinthian War (395–387 BC). The Spartans had some major successes in their land campaign but failed to capitalize on their advantage and stalemated. At sea, the Spartan fleet was defeated early in the war by an Athenian fleet. Taking advantage of this fact, Athens launched several very successful naval campaigns.

Alarmed by the rise of Athens, the Persians changed sides. Without their backing, Thebes and Athens had to seek a treaty with the Spartans. This treaty, widely known as the King’s Peace, stated that no polis (city-state) would be subject to another city-state- a clause very favourable to the Spartans. Armed with a letter of the treaty, Sparta went about Greece dismantling every alliance it felt threatened by.

The Boeotian Confederacy was not spared, thus withdrawing the other Boeotians from Thebes’ political control. Thebes’ power was further curtailed in 382 BC when a Spartan force occupied the Cadmea by a treacherous coup, placing favourable oligarchs in charge and exiling the democratic faction.

The Saviors: Epaminondas and Pelopidas

Plutarch’s Parallel Lives gives us the biography of Pelopidas, a Theban noble and a soldier. Plutarch describes him as a magnanimous leader and exemplary soldier. He was amongst the Democratic faction of Thebes who had been ousted after the Spartan coup.

Not much is known about Epaminondas. What we do know is from Plutarch’s biography of Pelopidas and briefly from Xenophon and Diodorus. From this patchwork, we know that Pelopidas and Epaminondas were close friends, possibly lovers. Epaminondas was a retired soldier and philosopher. As such, he was not deemed dangerous enough to be exiled.

Pelopidas and the other exiles made their way to Athens, where they were granted asylum. From here, Pelopidas secretly contacted Epaminondas and began planning on freeing Thebes from Spartan control. Epaminondas used to urge the Theban youth to hold wrestling matches with the Spartan soldiers stationed in Thebes. If the Thebans began celebrating their wins, Epaminondas used to shame them, telling them to not celebrate while they still held Sparta as their overlord.

By December 379 BC, the plan was ready to be put in action.

From his grand home in Thebes, the pro-Spartan leader Archias held a raucous party. Joining him were Hypates and Leontiades, the other pro-Spartan leaders. Believing that all resistance had been wiped out, they had laid down their arms and relapsed into a life of luxury and debauchery. Feasting and getting drunk, they waited for the night's main event: twelve hetairai (ancient Greece equivalent of geishas) promised by Charon (a noble in cahoots with Pelopidas).

Soon, the hetairai made their appearance. As an inebriated Archias beckoned one of them over, his face soon turned to shock as his throat was slashed violently by a hidden dagger. It was none other than Pelopidas and his comrades disguised as the hetairai. They immediately pounced upon their targets, making short work of them.

But the job was only half done. There was still the matter of the Sparton garrison stationed in Thebes. Epaminondas raised the citizens of Thebes in open revolt. They broke into the armoury and armed themselves. The next morning, the Spartans found themselves outnumbered and surrounded. They sought out a truce for safe passage, which the Thebans readily agreed to. But the Spartan image of military supremacy was tarnished.

The Rise of the Sacred Band of Thebes

Epaminondas and Pelopidas both knew that this was a fleeting victory. King Agesilaus II of Sparta was not a man who took slights pleasantly. Hell was soon going to pay them a visit, hard and fast, and the Thebans needed to be prepared.

No army had beaten the Spartans in open battle for the past century. They were the most elite soldiers in the entirety of Greece. By contrast, the Thebans did not have a standing army. All they had to offer were reservists with minimal training. Should this rag-tag army face the Spartans, there would be no contest. While Thebes consolidated its power back in Boeotia, Pelopidas, Epaminondas, and Gorgias realized that they needed a full-time elite fighting unit of their own.

But how could one raise esprit de corps in a newly formed unit? Spartans trained together since childhood, fought together in wars. Their camaraderie was based on real experience, over many years. The Thebans did not have time. To make up for this Epaminondas and Gorgias hatched upon a brilliant plan.

Plutarch says Epaminondas called up 150 of the social elite of Thebes loyal to the democratic regime. He then asked each of them to hand-pick a physically fit motivated Theban youth as their partner/lover. Thus a unit of 300 soldiers (150 couples) was formed who were bonded together by feelings of love and loyalty. Plutarch argues that a bond between lovers is stronger than that between tribesmen or clansmen, for no lover could afford to be seen as a coward in front of their beloved, nor could they let their beloved die before them.

It is considered that the inspiration for the idea was Hercules, Thebes’s most celebrated son. Despite being married, Hercules is said to have shared a passionate homosexual relationship with his charioteer and friend, Iolaus, which saw them become a formidable fighting force. Their extraordinary devotion to each other, as well as their legendary victories, were what Epaminondas and Gorgias were trying to achieve in the Sacred Band. Gorgias was the first leader of the Band. But he was soon replaced by the much younger and popular Pelopidas.

Pelopidas now had to train these 300 part-time warriors to match the most formidable fighting unit of their time. The Sacred Band were stationed at the Cadmea, funded by the Boeotian Confederacy, where they lived together, trained together to ensure they worked as a cohesive team, not individuals. Not only did they train to increase their strength and agility, but also drilled in spear and sword fighting, as well as how to fight in a phalanx, like the Spartans. Gorgias planned on making the Sacred Band the first line of the phalanxes of the entire army, behind whom the militia would rally. But Pelopidas realised that the true strength of the unit lay in a shock-and-awe hard-hitting mobile role.

First Blood: Battle of Tegyra, 375 BC

By the summer of 378 BC, the Spartans attacked Boeotia with a 20,000 strong army with King Agesilaus at its head. With just 6 months of training, Pelopidas knew that the Sacred Band was not ready yet. He needed more time to hone their skills. And this where Epaminondas came into his own.

Epaminondas knew the Spartan phalanx worked only in flat open terrain. So he stationed the Sacred band and his Athenian allies on higher ground. Agelisaus saw this and sent out some skirmishers to test the waters. They were quickly dispatched. But Agelisaus was confident that if he charged with his entire army, he would be able to break their lines. Agelisaus had used this strategy effectively in the Corinthian war back in 394 BC.

As the Spartans approached the Theban lines, the Sacred Band and their allies suddenly pointed their spears straight up instead of the enemy and lowered their shields, propping them against their left knees instead of hoisting them to the shoulder. Unsure of what was happening and fearing a trap, Agelisaus halted the Spartan army’s advance less than 200 metres away from the enemy. Then began a staredown of epic proportions.

Agelisaus was the first to blink. He ordered his army to retreat and leave the battlefield. This was a situation that required more thought than he had presumed. This psychological victory was a great morale boost to the Sacred Band. While not ready to beat the Spartans in battle, they were good enough to hold them at bay with mind games, at least.

But they could not hold off physical confrontation forever. In 375 BC, when the Spartan garrison defending the nearby city of Orchomenus momentarily left its post, Pelopidas decided it was too good an opportunity to turn down. Assembling the Sacred Band, they moved on Orchomenus only to find that the garrison had unexpectedly returned. Vastly outnumbered, Pelopidas was also not convinced the Band was ready for open battle. As such, he ordered his men to return to Thebes.

However, as they did so, Spartan forces, numbering between 1,000 and 2,000 troops, suddenly emerged before them at Tegyra. The Thebans were outnumbered, totally unprepared, and had no way to escape. According to Plutarch, at this one of the Sacred Band said to Pelopidas, ‘We are fallen into our enemy’s hands.’ Looking him square in the eye Pelopidas replied, ‘And why not they into ours?’ It was finally time to fight.

With a bloodthirsty roar, the Spartans charged towards them. Yelling above the noise, Pelopidas sent out his cavalry to intercept the enemy and quickly ordered his men into a tightly packed unit, just as he had trained them to do month after month, year after year. This was something the Spartans were not expecting. They still thought they were fighting a bunch of part-time peasants, not an elite unit. Believing that the Thebans were only desperate to get to the opposite side and flee, the Spartans opened up a path amidst their ranks. Instead, Pelopidas entered the gaps and started destroying the phalanx from within. Suddenly, the Sacred Band’s spears had torn through their ranks and killed their leader. At this, Pelopidas showed no mercy. The Sacred Band kept attacking, moving relentlessly and viciously forward. Stunned, and in total disarray, the surviving Spartans ran for their lives.

Although the battle was small, it was still a victory to cherish. The Spartans had never before been beaten by a smaller company than their own in a set-piece battle in recorded history. Now the Sacred Band was confident it could go toe to toe with the Spartan army, if not yet the 300 itself. But Epaminondas wasn’t so sure. He still thought there was work to be done and relentlessly analysed the Spartan phalanx for weaknesses to exploit.

Through his personal observation, and spies, he learnt that the Spartan army was not what it once was. By this time, there were perhaps fewer than 10 per cent actual Spartiates within its ranks. This was because Sparta was the only city-state in Greece that allowed men and women to inherit equally. Over time, this division of ownership meant fewer and fewer men inherited enough land to qualify and, as such, they could no longer devote their time to their training. This huge demographic shift now threatened Sparta’s long-standing dominance on the battlefield.

Death to the Tyrant: Battle of Leuctra, 371 BC

To make up for the lack of Spartiates, the Spartans became increasingly dependent on non-Spartan allies, known as Perioeci. But these troops were not always reliable. Essentially made up of slaves, or farmers obliged to fight for their Spartan overlords, they had no real loyalty to the Spartan cause. This was a fault line that Epaminondas thought he could exploit. If the Thebans could somehow break the Perioeci’s allegiance, then the whole Spartan army might collapse. The Macedonian author Polyaenus, in his Stratagems of War, stated that, in effect, Epaminondas wanted to catch a snake, crush its head and show his men how useless the rest of it was.

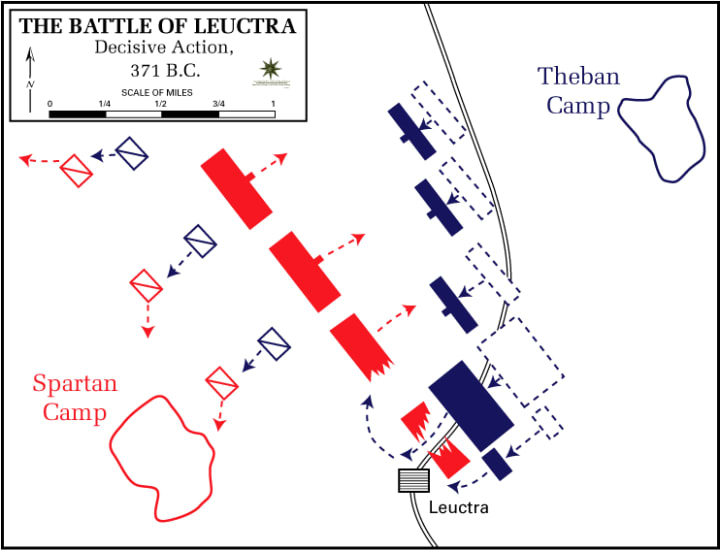

Epaminondas knew that the Spartan king Cleombrotus (Sparta had two kings at a time. Agelisaus was old and crippled with a leg wound at the time.) would place his elite Spartiates at the right flank of the army as was a time-honoured tradition. To counter this, Epaminondas placed his best troops on his left, directly facing Sparta’s best. He also noticed that the Spartan phalanx was a maximum of 12-men-deep.

To overwhelm the formidable Spartiate right, Epaminondas broke the convention and made his left flank phalanx 50-men-deep led by the Sacred Band. He also made the rest of his army stagger slightly behind the left flank, so that they may engage after the left phalanx had made contact.

Cleombrotus ordered his vast army of 11,000 Spartans and Perioeci to take Thebes once and for all. Marching to the plain of Leuctra, they were met by Pelopidas and his Sacred Band, as well as 7,000 troops. On this flat ground, Cleombrotus expected his phalanx to record an easy victory and to put an end to the Theban rebellion for good. It was clear to Epaminondas that his men were vastly outnumbered. If his plan did not get results quickly, then they would all be slaughtered. The Sacred Band’s attack needed to be one of brutal shock and awe if it was going to work.

Just as Epaminondas expected, the Spartan king, his commanders, and his best warriors lined up at the front, on the right of the phalanx, eight ranks deep. In response, he quickly ordered a bulk of his formation to assemble on the left, behind the Sacred Band. Cleombrotus could see what was happening but before he could act Pelopidas gave the signal to attack. At this, the Sacred Band launched themselves into the right of the Spartan phalanx, with over fifty ranks of shields and spears behind them.

Twenty of the Sacred Band were instantly killed by Spartan spears, but they stuck tight together, the weight of their ranks ploughing them forward, causing the Spartan wall to crack under the strain. As gaps suddenly opened, carnage erupted. Spartans were stabbed and slashed, while Pelopidas tore through the bodies and grabbed King Cleombrotus. Stabbing him again and again, Pelopidas left nothing to chance, ensuring that Cleombrotus was the first Spartan king to be killed in battle since Leonidas. The king’s death sent a shockwave through the rest of the Spartan army. Not only had the 300 been defeated but their king was dead, along with over 400 of the 700 Spartiates.

As Epaminondas predicted, the slaves and allies of Sparta now decided to retreat. His strategy was a triumph, representing the most shattering defeat in the history of Sparta, and signalling the end of Spartan dominance on the battlefield. Since the number of Spartiates was already small, the death of over half of them saw the Spartan army gradually disintegrate. In its absence, the Sacred Band became the most elite military force in Greece, while they had also ensured that Thebes remained free.

Total Annihilation: Battle of Chaeronea, 338 BC

Not much is known about the exploits of the Sacred Band following their victory at Leuctra. The next time they appear in historical records is nearly 40 years later, at Chaeronea to face a threat from the north: the Macedonians.

In 367 BC, King Philip II of Macedonia was taken political prisoner of Thebes where he received military education from Epaminondas and became a lover of Pelopidas. Both of these relationships taught him how a previously amateur army became Greece’s most elite fighting force.

On his return to Macedonia in 359 BC, Philip brought radical changes to the outdated phalanx, replacing the outdated hoplite spear with the sarissa, an 18–20ft pike, to give his men further reach. The long pikes meant that any opponent would have to face multiple layers of pointed speartips before reaching the phalanx proper. He also made his phalanx very flexible, able to respond to any situation rapidly. in addition to his new phalanx, he had another ace up his sleeve: his 18-year-old son Alexander and his crack “Companion Cavalry” unit.

With his deadly phalanx, he defeated the barbarian hordes threatening his northern borders and soon turned his army south, towards Thebes and Athens. He met the Theban-Athenian army at Chaeronea, where he engaged them in battle.

The Sacred Band of Thebes held the position of honour in the right flank, where they were engaged by the Macedonian phalanxes. While they were engaged with the phalanxes and victory uncertain for the Macedonians, Alexander led the charge of his Companions, and ‘was the first to break through the main body of the enemy, directly opposing him, slaying many; and bore down all before him — and his men, pressing on closely, cut to pieces the lines of the enemy; and after the ground had been piled with the dead, put the wing resisting him in flight’. This was the Sacred Band’s only defeat in open battle in history.

After Alexander’s famous victory, Athens was forced into an alliance with Macedonia, while Thebes lost its rich agricultural lands in Boeotia, with the Sacred Band no more. According to Plutarch, Philip was extremely moved by the Band’s courage, having of course once been so close to their founders, Epaminondas and Pelopidas:

After the battle, Philip was surveying the dead, and stopped at the place where the 300 were lying, all where they had faced the long spears of his phalanx, with their armour, and mingled one with another, he was amazed, and on learning that this was the band of lovers and beloved, burst into tears and said, ‘Perish miserably they who think that these men did or suffered aught disgraceful.’

So touched was Philip at the sacrifice of the Sacred Band that it appears he built a monument to them, which was discovered by a British tourist in 1818. While out horseback riding near the battlefield, the tourist tripped over a rock that, upon some digging, was revealed to be a massive stone lion. Inside the monument, 254 skeletons were later discovered, believed to be those of the Sacred Band, with the lovers wrapped in eternity to each other.

Originally posted on medium.com

About the Creator

Diptangshu Karmakar

Medical student. Certified nincompoop. Questionable bookworm and painter. Common sense: defenestrated. Interested in anthropology, evolution and history, especially military.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.