Being Jewish in the US Military

How Cultural and Religious Isolation Strengthened My Faith

My first experience of Jewish life in the military came early, and in the form of a person: a Naval Chaplain, tasked with tending to the spiritual needs of the several hundred recruits in my barracks.

When my Division Commander took a break from collective and corporal punishment to tell us a Rabbi was coming to visit, I heard several of my peers utter "a what?" These same people would become my closest friends, and I soon began to discover that I served as the unofficial ambassador of the Jewish people while in boot camp and beyond. Many of the other recruits had came from small towns in Texas, Georgia, California, i.e., places where Jews don't live. I was there to answer any questions they had accumulated over the previous two decades—a role I continue to play, on occasion, in my professional life—the vast majority of which consists of either debunking or confirming common ethnic stereotypes, explaining why Jews wear "the little hat," or explaining how I get by in life without eating bacon.

But just like the other recruits, the military was, to me, completely foreign at the time. Cultural isolation was not something I was accustomed to. Naval Station Great Lakes was just 45 minutes away from the largely urbanized and heavily Jewish Northside neighborhoods and suburbs of Chicago, the place I call home. But it might as well have been 45 hours away. From the Kosher bakeries of Rogers Park, to the Chabads of West Ridge, to the Jewish day schools of Skokie—being Jewish was, in my youth, nothing out of the ordinary. I studied Hebrew for four years at a public High School, was an active member in Jewish student organizations, and taught Hebrew and Jewish history to 3rd graders at the Beth Emet Synagogue in Evanston my junior year. I worked at an Israeli owned Shawarma chain. I went on birthright to Israel the winter following my senior year. It was more common for Jewish kids in my neighborhood to join the IDF than the US Military, something many of my friends and acquaintances had done and something I considered myself.

But beyond the tight-knit ethnic enclave of Chicago's Northside and Northshore was the unspeakable taboo of Jewish poverty, something I came to know just as well as the synagogues and kosher bakeries on Touhy Avenue. My family had settled in a small one bedroom apartment not far from Howard Street Station, something we had to keep quiet about to avoid eviction. Our building manager, a Montenegrin refugee from the wars in Yugoslavia, paid little attention to both us and the building, something we were grateful for at the time.

My mother had gotten a job at one of the high end restaurants in Chicago's downtown, serving and waiting on many wealthy Jews from Lincoln Park and Edgewater, taking the redline every morning and night to get to work as we didn't own a car. She would come home each night to tell us about all the small and big time celebrities she got to meet: The Mayor of Chicago, various ABC reporters, social activists, and a handful of big name politicians and Broadway stars from Chicago's theater scene. My brother, sister, mother, and I would be sitting in the dining room, which doubled as my mother's bedroom, laughing and joking late into the night.

My family eventually found much more suitable living accommodations. Mom would go on to be a very successful nanny and estate manager in the Northshore. Despite this, those few years in my early adolescents were some of the happiest times of my childhood. Struggle bred love and belonging, a fact I would be reminded of several years later while serving in the US Navy.

This brings me to the reason I joined. The military was for me what it was for so many other poor kids: an open door. Going to college, much less medical school, was only attainable through five years of honorable military service and the benefits that came with it. Despite my humble roots, I had dreams that I never let go of, and the military was and is the way in which I'd turn those dreams into accomplishments. Straw into gold, as they say.

My recruiting station was in Ravenswood, a largely Arab neighborhood on Chicago's Northside. Jews nor the U.S. Military were particularly welcomed, a factor that led the center to close down shortly after I left for boot camp. I remember a display of Palestinian flags and TAP Boyz gang graffiti on my walk from the recruiter to the train station, a walk I made only a handful of times. Arab kids wondered what I, with my "Go Navy" shirt and Star of David necklace, was doing in "their neighborhood." Within a week, I enlisted as a Hospital Corpsman. A month later, I left home at age 19.

I would spend the next year in various training schools and courses to earn all the necessary credentials as a Corpsman. I attended makeshift Jewish services in Fort Sam Houston Texas, during my initial medical schooling. I was one of just a handful of Jews in all of Eastern North Carolina during my 6 months at Camp Lejeune. I didn't pay much attention to my religion in this period of seemingly never ending military training, as doing so appropriately was next to impossible.

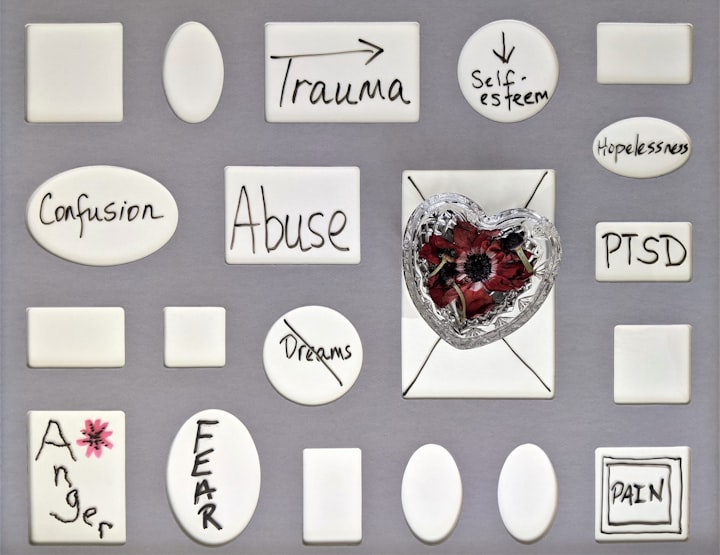

I had originally expected to get assigned to a Marine battalion—to serve as the first tier of medical care for Marines, after receiving the training to do so. Having joined at a time of relative peace, I was assigned to an inpatient psychiatry unit at a military hospital. My speciality in combat medicine was quickly replaced with interest and experience in mental health, psychiatric illness, substance abuse, and combat-induced PTSD.

It was at this time that I finally had the chance, time, and energy to rediscover, or perhaps simply discover Judaism. Being Jewish in Chicago or Evanston or Skokie was not like being Jewish in the military. It required no internal effort. All I had to do in order to expose myself to Jewish life was to walk out my front door, go to school or go to work. I did not observe Judaism in any meaningful way in my teenage years. I was another "cultural Jew" who paid little attention to Judaism or the roots of the religion. I felt Jewish enough without Judaism.

The military was different. There was no daily use of Hebrew, no Jewish day schools or Chabads next to the base exchange, no automatic excusal from the high holidays, no kosher bakeries around the corner. The factors that made me Jewish were now internal, not external. I had to put significantly more effort into my religious and cultural identity. It was only then that I began to actually learn about the religion of Judaism. Just like the other recruits in my division, I too had questions, and I wanted answers. The military and the cultural isolation that came with it forced me to really question what it was that made me a Jew. Judaism was now deeper, more profound, more intimate, and inevitably more complex than ever before.

Enlisting was the ultimate test of faith. In addition to giving me a salary, a car, the opportunity to go to college and eventually medical school—things I wouldn't otherwise have—the military brought me closer to G-d. I learned how (and why) to be a Jew in a completely non-Jewish environment. Judaism and God was not confined to the synagogues and communities of Chicago's Northside. It always was and continues to be within my heart.

About the Creator

Ezra Berkman

Life is so much better when you write it down.

Poet and novelist. All for my own enjoyment.

Currently writing a memoir and an alternate history novel "Where the River Narrows"

I may be reached personally at [email protected]

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.