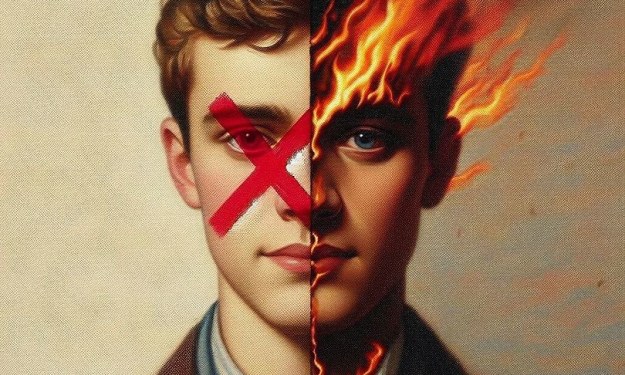

The Myth of Top Management Team

Do we really have a team

The article "The Myth of the Top Management Team" by Jon R. Katzenbach in Harvard Business Review was quite interesting. Even though it was written in 1997, this article accurately depicts management in most companies today. The article addresses the overall parten of team bonding between executive management in companies.

Even in top firms, top teams seldom work together. Real teams need the discipline to function properly. Leadership needs to distinguish between team and non-team opportunities. The CEO runs meetings, sets the agenda, and gets member buy-in. The executive council works well under one head. It seldom applies team fundamentals to the entire group or infrequent subgroups.

First, elite teams struggle to find purpose. A factory floor crew may express a purposeful purpose. "Improve the company's performance" doesn't concentrate on a team. Second, defining performance targets is difficult. Frontline teams have distinct, recurrent, and quantifiable objectives. However, top-level team objectives are tougher to define. They must come from corporate and company goals, long-term finances, market share, and CEO performance. Thus, senior executives typically find goal planning for a "top team" unclear and uninspiring. Third, the proper skillset is frequently lacking. However, top-level assignments are generally based on formal status rather than competence. Any executive team may have a decent mix of abilities, but that doesn't mean they have the right skills for the project. Fourth, most teams demand significant time. Each team must consider its members' time, abilities, and duties while creating a workable strategy. Fifth, shared responsibility is tougher to build and less battle-tested. Sixth, non-teams fit power. Due to their clear leadership and responsibility, working groups and organizational units match this model better than true teams. Top executives are overachievers who learn to operate in a hierarchy early on. Communication forums rather than performance units, such groupings are generated randomly. Seventh, individuals work quickly. A seasoned leader understands the team's objectives and strategy. Real teams require more time, particularly when setting objectives and discussing working methods.

Executives often dislike lengthy processes of "forming, norming, and storming" that initiate team endeavors. Top-level collaboration "is unnatural because it's impossible. Leaders that emphasize team and individual leadership don't see non-team conduct as a failure. Top leaders may integrate rather than replace. Best CEOs emphasize individual responsibility for profit, market outcomes, speed, and growth. They want excellent performance from executives. Team performance and senior leadership discipline frequently collide. Most top CEOs follow these leadership standards to achieve consistent success. Top leaders hold managers responsible by rewarding and disciplining them for meeting stated goals. Respect and collaboration help a team hold each other responsible for outcomes. A team's purpose and objectives may be significant but not urgent or crucial.

Executives must prioritize company-wide challenges. Executives choose risks, resources, and strategies on their own. Open conversation, dispute resolution, and teamwork enable team judgments. Regardless of their firm job, team members are chosen for their task-specific talents. Executives manage more people and assets as they become more efficient and valuable.

A skilled manager may make the team more effective. Each discipline requires executive discretion to apply. The finest leaders try to apply the two, knowing they won't always do it perfectly. Three exams determine team performance. These criteria apply regardless of a team's corporate rank. First, the group must create company-valued work-products. Second, people must learn to share leadership. Third, group members must share responsibility for outcomes. Wolraich: A group with varied abilities improves performance with a collective work-product. Four Browning-Ferris Industries executives raised $500 million in 1995. These success examples were fueled by urgency, if not catastrophe, but top leaders can collaborate. An organizational-unit "team" is led by its official leader. When in a team, executives must give up their own accountability for what occurs under their watch. "We hold one another responsible" rather than "The boss holds us accountable" shows that all team members must be committed.

The best senior-leadership groups seldom work as teams, but they may when unforeseen situations arise. Waiting for a catastrophic event to build a team may lose key chances to harness team performance. Exxon Mobil's CEO Lucio Noto sought top-level assistance in 1994 to improve the company's strategic position.

Frank Noto's top executives developed a new approach to accelerate leadership development. They had to compile performance data about former colleagues. "Our major goal is growth, not assessment," rebalanced the team's activities. Evaluation tasks might be assigned to formal organizational-unit leaders and teams.

The executive office should prioritize company-wide growth. They created a leadership-development profile for middle and senior managers. The Opportunity Development Council finds leadership development opportunities. The company's top 100 jobs were evaluated more rigorously. Opportunity-development and assignment-matching were also revamped.

Leadership teams like Mobil's are like musical ensembles. Members establish mutual respect and belief in what they can achieve together as they appreciate one other's talents. A group can't influence its work until it keeps working together. Any group—top, middle, or front line—can unlock its team performance potential with a few easy recommendations.

Leadership groups may boost performance by identifying actual team opportunities before a large event. Only valuable work-products and leadership contributions work in teams. Avoid distracting executives with empty possibilities. They may include a unit leader's direct subordinates, cross-functional supervisors, or the whole company. The greatest leadership teams master numerous methods rather than sticking to one.

Executives must decide whether actual team performance is worth the time. When the leader knows best, single-leader groups are swift, efficient, and strong. Individuals are excellent for projects that do not need a composite mix of talents.

High-level CEOs misuse executive leadership discipline, hurting team performance. Balance is elusive. Top teams sometimes misuse team discipline after seeing its power. Leaders who stick to what worked in the past will always struggle.

Top executives should watch their leadership styles. Most team leaders recall the frustration and uncertainty that followed.

About the Creator

Dr. Sulaiman Algharbi

Retired after more than 28 years of experience with the Saudi Aramco Company. Has a Ph.D. degree in business administration. Book author. Articles writer. Owner of ten patents.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sulaiman.algharbi/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.