Choosing the Best Level of Editing for Your Writing

Which type of editing is right for your needs?

Whether you have written a novel, are sending emails to potential clients, or are developing human resource manuals, having a second set of eyes on your written text can help ensure that your writing is the best it can be. By working with a professional editor, you can go beyond grammar checks to ensure that your writing is clear, effective, and on message while also being appropriate for your target reader.

Hiring an editor can be a confusing process, mostly because there are so many different kinds of editing. Therefore, before looking for an editor, it is important to know what kind of editing you need for your specific text.

Although editors may use slightly different terminology to describe their services, editing generally falls into three areas: big picture, fine-tuning, and final polish.

Big Picture Editing

Big picture editing can include editorial assessments, structural editing, and developmental editing. For these types of editing, the editor is looking at the chapter or scene level to make suggestions and recommendations on the content of the writing.

Editorial Assessments

If you’ve ever asked friends or colleagues to read your writing and tell you what they think, you’ve basically received an editorial assessment, although an editor approaches such an assessment with professional training in and understanding of the principles that make specific types of writing effective.

Editorial assessments provide broad suggestions about how to improve the major components of your text, such as the organization or information or the timeline/development of your story. They can include noting areas that might need to be cut or completely revised as well as areas that are missing from the current text. The assessment comes in the form of a letter, and no notes are made on the manuscript itself.

Structural and Developmental Editing

Structural and developmental editing are quite similar in scope, so here we present them together. Note that if you are considering an editor who offers both, be sure to ask for clarification in distinguishing the two.

Structural/developmental editing examines the overall structure of the text to identify what is working and what is not. The focus is on the overall flow of the story and information. It determines whether the information (e.g., chapters, scenes) is presented in a logical manner and if the reader receives enough information to proceed to the next chapter or scene. If not, the editor may suggest moving large chunks of text around and even deleting unnecessarily repetitive sections.

Structural/developmental editing also determines what is working and what is not in terms of overarching themes. In non-fiction writing, this can include the rate at which information is presented as well as whether the information is organized in meaningful chunks. For creative writing, the editor will study whether characters and their development, plot lines, and pacing are effective.

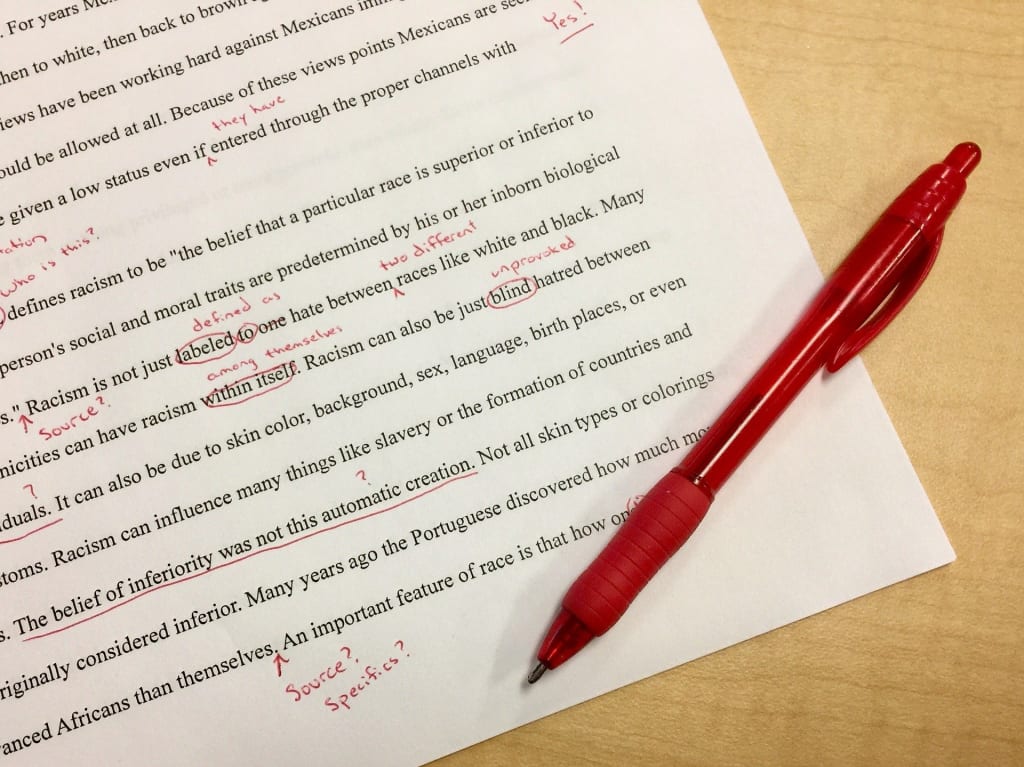

Both structural and developmental editing identifies “holes” in the information or story and makes suggestions for fixing them. It includes feedback on the content that is provided on the manuscript itself (for an example, see Beth Jusino’s screenshot). As a result, structural/developmental editing is much more labor intensive than an editorial assessment.

No big picture editing includes any reviews of the writing itself to eliminate grammar mistakes or typos or to strengthen the writing itself.

Fine-tuning the Writing

Once the overall structure and story are finalized, the writer needs an editor who can examine the mechanics of the writing. This level of editing includes copyediting and line editing, which are similar but adopt a somewhat different focus.

Copyediting

A copy editor will make corrections to the text itself to fix grammar problems like spelling, capitalization, verb tense, and word usage. A copy editor knows all those obscure grammar rules and when to apply them. Copyediting also identifies inconsistencies in the text, such as how places are named or described. For example, is it Baker Street or Baker St.?

Line Editing

Line editing adopts a similar approach as copyediting, but with a focus on the craft of the writing. In other words, a line editor will study the creative choices that the writer makes to ensure consistency and clarity. For example, do the writer’s voice and style contribute to the emotional flow of the story and are they consistent throughout? A line editor will fix clunky, unclear writing to create tight, powerful prose.

Jami Gold provides comprehensive lists of the skills that copy editors and line editors use during their editing process.

Final Polish

When you have what you believe is the final version of your text and you’re ready to publish it, you might want to hire a proofreader and/or fact-checker.

A proofreader reviews the entire text to make sure that no new typos have slipped in during previous editing and revision stages. Proofreaders can also spot errant punctuation, irregular formatting, and outstanding inconsistencies. A proofreader will not make extensive changes to the text, but will instead fix any glaring errors.

A fact-checker can be a vital part of your editing team, especially if you include information from the real world in your manuscript. The fact-checker will verify names, dates, locations, timelines, and similar details to ensure that the text is accurate.

A Final Word: Editing software and apps

Editing software and apps like Grammarly, the Hemingway Editor, and even Microsoft’s grammar and spellcheck are helpful tools when you are writing, but they cannot replace a well-qualified editor. Writers can use these tools to produce the cleanest document possible to provide to their editor, but none of these tools are 100% correct.

When using these tools, writers need to understand grammar and word usage so they can evaluate the suggestions to determine which ones are appropriate. In addition, these tools cannot assess the text for the writer’s creative decisions (e.g., characterizations, poetic wording), style guide requirements (e.g., Chicago Manual of Style or in-house guides), or specific styles of writing (e.g., an author’s voice or “legalese” in corporate communications).

For side-by-side comparisons of one grammar tool versus a human editor, check out David Alan’s review and Tonya Thompson’s review.

If you enjoyed this article, you might enjoy reading about critique groups:

About the Creator

Nanette M. Day

Exploring the world one story at a time, especially from unheard voices. Sometimes I share random ramblings, sent straight to your inbox. Life’s more humorous lessons are courtesy of my dog.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.