Black Hole Tragedy

The Black Hole of Calcutta was a dungeon in Fort William, Calcutta, measuring 4.30 × 5.50 metres (14 × 18 feet), in which troops of Siraj ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, held British prisoners of war on the night of 20 June 1756.

Background

Fort William was established to protect the East India Company's trade in the city of Calcutta, the principal city of the Bengal Presidency. In 1756 India, there existed the possibility of a military confrontation with the military forces of the French East India Company, so the British reinforced the fort. Siraj-ud-daula ordered the fortification construction to be stopped by the French and British, and the French complied while the British demurred.

In consequence to that British indifference to his authority, Siraj ud-Daulah organised his army and laid siege to Fort William. In an effort to survive the battle, the British commander ordered the surviving soldiers of the garrison to escape, yet left behind 146 soldiers under the civilian command of John Zephaniah Holwell, a senior bureaucrat of the East India Company, who had been a military surgeon in earlier life.[5]

The Holwell account

A fenced display of the Black Hole of Calcutta. (1908)

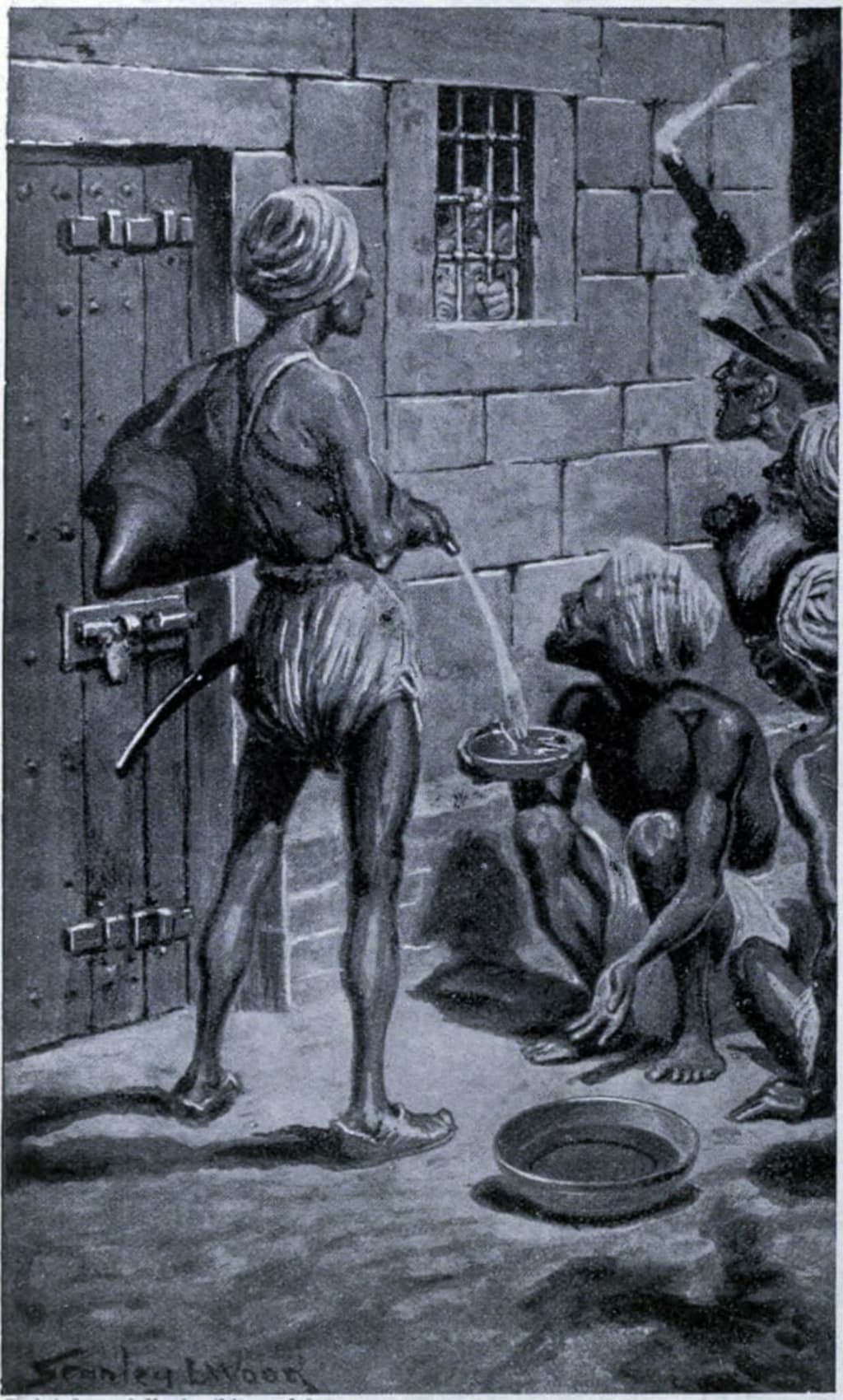

Holwell wrote about the events that occurred after the fall of Fort William. He met with Siraj-ud-Daulah, who assured him: “On the word of a soldier; that no harm should come to us”.[6] After seeking a place in the fort to confine the prisoners (including Holwell), at 8.00 p.m., the jailers stripped the prisoners of their clothes and locked the prisoners in the fort's prison—“the black hole” in soldiers' slang—a small room that measured 4.30 × 5.50 metres (14 × 18 feet).[7] The next morning, when the black hole was opened, at 6.00 a.m., only about 23 of the prisoners remained alive.[5]

Historians offer different numbers of prisoners and casualties of war; Stanley Wolpert reported that 64 people were imprisoned and 21 survived.[5] D.L. Prior reported that 43 men of the Fort-William garrison were either missing or dead, for reasons other than suffocation and shock.[8] Busteed reports that the many non-combatants present in the fort when it was captured make infeasible a precise number of people killed.[9] Regarding responsibility for the maltreatment and the deaths in the Black Hole of Calcutta, Holwell said, “it was the result of revenge and resentment, in the breasts of the lower Jemmaatdaars [sergeants], to whose custody we were delivered, for the number of their order killed during the siege.”[6]

Imperial aftermath

The remaining survivors of the Black Hole of Calcutta were freed the next morning on the orders of the nawab, who only learned that morning of their sufferings.[10][2]: 71 After news of Calcutta's capture was received by the British in Madras in August 1756, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Clive was sent to retaliate against the Nawab. With his troops and local Indian allies, Clive recaptured Calcutta in January 1757, and defeated Siraj ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey, which resulted in Siraj being overthrown as Nawab of Bengal and executed.[5]

The Black Hole of Calcutta was later used as a warehouse.[citation needed]

Monument to the victims

The Black Hole Memorial, St. John's Church, Calcutta, India.

In memoriam of the dead, the British erected a 15-metre (50') high obelisk; it now is in the graveyard of (Anglican) St. John's Church, Calcutta. Holwell had erected a tablet on the site of the 'Black Hole' to commemorate the victims but, at some point (the precise date is uncertain), it disappeared. Lord Curzon, on becoming Viceroy in 1899, noticed that there was nothing to mark the spot and commissioned a new monument, mentioning the prior existence of Holwell's; it was erected in 1901 at the corner of Dalhousie Square (now B. B. D. Bagh), which is said to be the site of the 'Black Hole'.[9]: 52–6 At the apex of the Indian independence movement, the presence of this monument in Calcutta was turned into a nationalist cause célèbre. Nationalist leaders, including Subhas Chandra Bose, lobbied energetically for its removal. The Congress and the Muslim League joined forces in the anti-monument movement. As a result, Abdul Wasek Mia of Nawabganj thana, a student leader of that time, led the removal of the monument from Dalhousie Square in July 1940.

Literature

Thomas Pynchon refers to the Black Hole of Calcutta in the historical novel Mason & Dixon (1997). The character Charles Mason spends much time on Saint Helena with the astronomer Nevil Maskelyne, the brother-in-law of Lord Robert Clive of India. Later in the story, Jeremiah Dixon visits New York City, and attends a secret "Broad-Way" production of the "musical drama", The Black Hole of Calcutta, or, the Peevish Wazir, "executed with such a fine respect for detail ...".[12] Kenneth Tynan satirically refers to it in the long-running musical revue Oh! Calcutta!, which was played on Broadway for more than 7,000 performances. Edgar Allan Poe makes reference to the "stifling" of the prisoners in the introduction to "The Premature Burial" (1844).[13] The Black Hole is mentioned in Looking Backward (1888) by Edward Bellamy as an example of the depravity of the past.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.