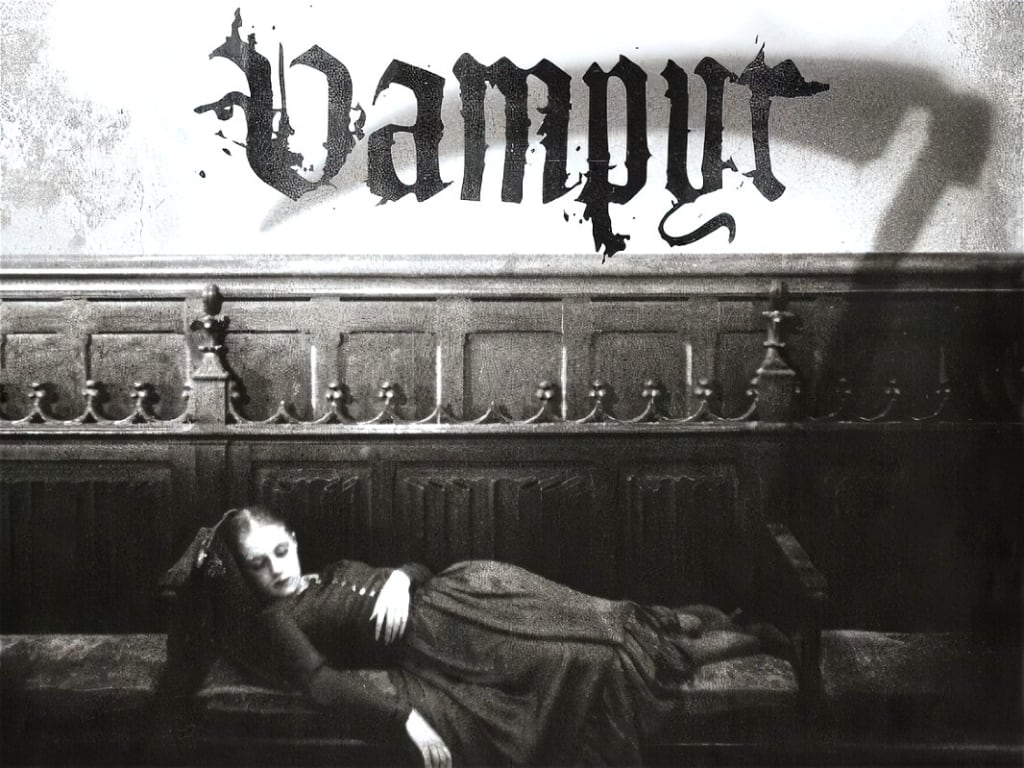

Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr is a hallucinatory light and shadow show that is as visceral as the subconscious mind's influence on the body--it seems to recall sights and sounds that the viewer knows instinctively--buried memories from some alternate, midnight life in another dimension. Conventionally, it's a vampire tale, an adaptation of elements from In a Glass Darkly by J. Sheridan LeFanu, who penned the classic vampire novella Carmilla (1872) long before Bram Stoker ever set his sights on a Transylvanian count. The forbidden eroticism hinted at in that blood-soaked old gem is nowhere apparent here, in the cinematic story of Allan Gray (Nicolas De Gunzberg, credited as "Julian West"), a man who seems to walk like a somnambulist, but with a wide-eyed sense of wonderment at the strange sights he encounters during his nightmare sojourn.

Gray, we are informed, is obsessed with his studies of vampires and the supernatural. Walking through the countryside, carrying a fishing net, he comes upon an inn with an angel for a sign. Seeing the setting sun descend behind it in a dishwater sky, he gets a room and is surprised when an old man (Maurice Shultz) enters his room in the night, leaving behind a book with an inscription for him, "In the event of my death."

The book, much like in Murnau's Nosferatu (1922), is a convenient history of vampires--all the better to school Alan in the ways of the Undead as he proceeds from the inn to an isolated manse, wherein the man from his dream or nighttime vision (but if he left his book behind, how can it simply be a dream?) seems to be shot down by a shadowy presence at the window. Already, Alan has seen gravediggers that operate in reverse (as in shovelfuls of dirt fly up to meet them, to be placed in the grave to fill it), and shadows that disconnect from the physical body casting them away, to go wandering around independent of their physical masters.

The preceding is a mind-numbingly slow, shuffling cadaver gait, and the film, as short as it is, seems to unwind over a considerable amount of time. The old man lingers at the edge of death; his daughter Léone (Sybille Smitz), reclines in a bed herself, the seeming victim of a nocturnal visitation by an unseen revenant (this is later revealed to be Marguerite Chopin, the vampiress). Her dialog is simple and sparse, with a few lines here and there. And for that touch of artistic license and similar such, the film transcends being simply a gloomy old vampire film--its surrealistic touches hint at the new, experimental movements in art and cinema of those Weimar years, before the ascendancy and strangling domination of fascism in the wake of Hitler's victories.

Conentionally the plot makes little sense--or at least, it may be founded on a conventional theme (vampirism), but it is executed in a manner that might have made Bunuel or Cocteau proud, assuming they saw it. The imagery, while restrained, lies beneath the surface of the viewing experience, and we are uncertain as to whether or not we are experiencing events as Alan experiences them, or simply being given a window into the troubled sleep of a young man whose mind is bent toward the macabre, the occult; ruminations upon death, in other words.

And it is upon the grinding wheels of cosmic justice that the film focuses during its conclusion. Without giving away too much, we are left with images as indelible as any in Dreyer's masterful masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), with Renee Marie Falconetti and Antonin Artaud. A mad professor (Jan Hieronimko, a stand-in for Van Helsing), arrives on the scene. He has the vague mien of an Einstein. But, is he truly on the side of the living, or right and "good"? Being caught in a mill, the gears of which are shown turning and twisting prominently, he is suffocated, drowned by a rain of--flour? We aren't certain. The machinery of cosmic justice, perhaps, is what is being subtly exposed here--and the guilty party crushed under an avalanche of the life-sustaining food. Which, for humans, isn't blood.

Denn die toten rieten shnell--"For the dead travel fast." But not here. Here, the dead are slow, cryptic, and full of dark, and troubled dreams. If cinema is the equivalent of dreaming awake, then Vampyr is an old and recurrent dream of the magnetic south of our dreams of death and dust.

Vampyr (1932 - Carl Theodor Dreyer) Score by Jay Danley

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Reader insights

Nice work

Very well written. Keep up the good work!

Top insight

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Comments (1)

Another interesting revelation to which I shall have to return later, Tom. Interesting review.