'Out of the Trenches by Christmas

A Brief History of the Ford Peace Ship

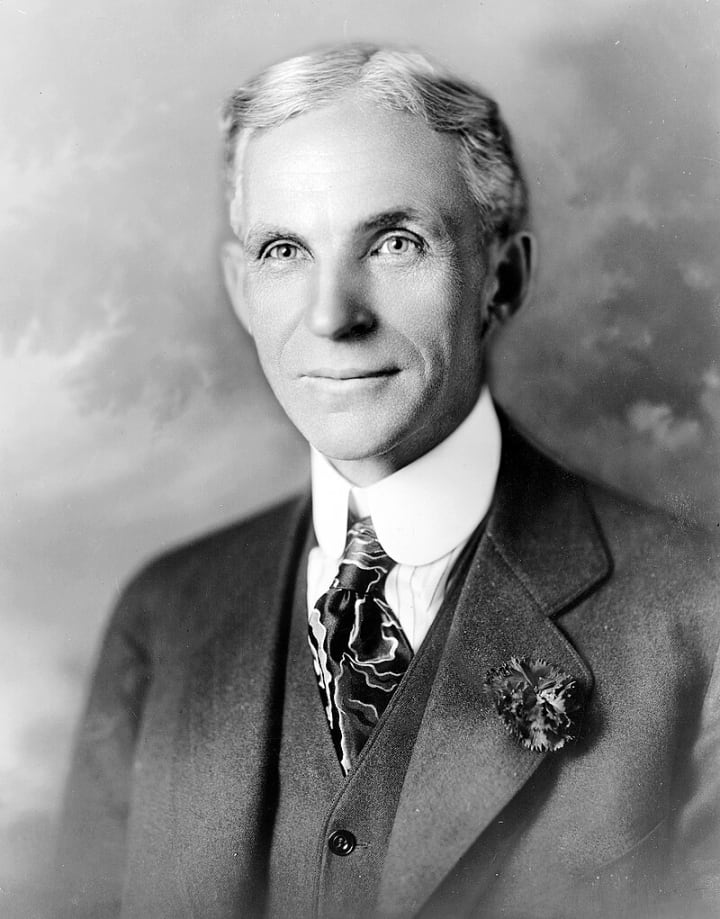

At 1:15 p.m. on December 4, 1915, one of the most powerful and popular men in the country arrived at a pier in Hoboken, New Jersey. Waiting for him were thousands of spectators and well-wishers to see him on his journey. Through a circus atmosphere that one paper called “so grotesque as to be beyond belief,” Henry Ford, dressed in a brown overcoat, derby hat, and carrying a walking stick, pushed his way through the crowd to board the cruise liner he commissioned for one specific purpose — to bring peace to a world at war.

Ford, the Man

Henry James Ford was born on July 30, 1863, the second of six children to Irish immigrant William and his wife Mary. William Ford was a farmer, but his son was a tinkerer. In 1879, the 16-year-old Ford left the family farm to work at nearby Detroit as an apprentice mechanic, eventually becoming the Chief Engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company in 1896. It was there that he met (and became lifelong friends with) Thomas Edison. With Edison’s encouragement, Ford continued his experiments with designing and building automobiles, and in 1903, with $28,000 in working capital, formed the company that bears his name today.

Ford’s innovations in mass production fulfilled his promise to mass produce a car that would “be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one.” By 1912 his Model T controlled 96% of the low-cost car market. And millions of Model Ts on the road meant millions of dollars for Ford and his company; in 1914 his company generated a cash surplus of $48 million, and Ford had $1.5 million in his personal banking account.

With his adoption of the $5 work day Ford was hailed as a man of the people and a classic American success story. But Ford had his faults; one was speaking off-the-cuff, the other never doing anything he didn’t want to — both that would be on full display when he decided to become an outspoken critic of World War I.

“Out of the Trenches by Christmas”

Diplomacy in Western Europe in the early 20th century was driven by the idea of achieving a “Balance of Power.” Countries on the continent formed alliances with each other in an attempt to keep one side (Axis or Allies) from getting the upper hand over their rivals. The actual result was such a complicated web of political and military alliances that one minor incident could set off a chain of events that would plunge Europe into war.

That incident occurred on the 28th of June 1914, when the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated. A month later, when the Austrian-Hungarian Empire invaded Serbia, everybody was obligated to declare war against everybody else, and World War I was on.

Ford began expressing his anti-war views in the Spring and Summer of 1915. Blaming “moneylenders and arms manufacturers” (among others) for starting the war to line their own pockets, Ford went so far as to express his willingness to fund an international peace program.

Ford’s seeming support drew peace activists like moths to flame. But Ford had in his employ people whose purpose was to protect him when his words sometimes got ahead of his intentions. Ernest G. Liebold was one of these people. Officially a secretary, Liebold’s real job was to smooth the waters for his boss when his mouth got ahead of him. When he found out that Ford was promising to fund world peace, Liebold did his job and efficiently kept the peace activists at bay. But even Liebold couldn’t be on the job around the clock; in November 1915, while Liebold was absent during a brief business trip out of town, Ford met with a peace activist who convinced him to put action behind his words.

That peace activist was Rosika Schwimmer, a Hungarian-born writer and outspoken advocate for women’s suffrage, birth control, and trade unions. Armed with a briefcase full of “secret” documents she claimed outlined the belligerent nation’s desire for a neutral conference, she met with Ford and his wife Clara at their home on November 17, 1915. Her documents later turned out to be neither secret nor proving that the warring countries wanted anything more but to fight for a while was a fact that was reserved for the future.

Ford and Schwimmer could not have been more opposite. Rosika was a Jew; Ford was an outspoken anti-Semite. Schwimmer’s views on women’s issues were completely opposite to those of Ford, who believed that women had no place in business. And yet Rosika must have said something that charmed Ford because the next day he was on a train to New York to further the cause of peace.

At a dinner in New York shortly after arriving, another peace activist named Louis Lochner suggested that a ship should be charted to travel to Europe to spread the peace message. Ford immediately seized on the idea and set himself to find a ship that could do just that. Ford found his ship in the Oscar II of the Scandinavian-American Line. Reserving the first and second-class berths, he set up shop at the Biltmore Hotel and began sending telegrams of invitations to every dignitary in the country, proclaiming that it was time “for a few men and women with courage and energy…to free the goodwill of Europe that it may assert itself for peace and justice, with the strong probability that international disarmament can be accomplished.”

The formal invitations went out on 27 November, one week before sailing. But with all the fanfare and promotion associated with the event, in the end, no important businessman, scientist, educator, or member of the national government accepted. Even Clara refused to go and worked to convince her husband not to go either. Most major newspapers and wire services sent reporters. All that is, except Ford’s hometown Detroit newspaper — his friends had persuaded them not to send somebody that might file an embarrassing story about the trip.

While chaos reigned at the Biltmore, Rosika occupied herself by spending $57,000 of Ford’s money to ready the Oscar II for its peace mission. Rosika enjoyed the alms of her new benefactor, once remarking “All I have to do is wave my hand for what I think is necessary for our Peace Mission and lo! it appears.”

The day of December 4th, 1915 was bright and cold as close to 15,000 people turned out at the Oscar II’s berth in Hoboken, New Jersey to see her off. It turned out to be as chaotic and unorganized an affair as everything else associated with the Peace Mission, with nobody sure who was on board and who wasn’t. Ford was the last to board. Ford stood at the rail and threw roses to his wife Clara and his son Edsel as the ship pulled away from the dock to begin its mission to end World War I.

The Ford Peace Ship

The Oscar II began its journey in calm seas, but for the passengers, the chaos had only begun. It took four days at sea to complete the final passenger manifest. In all, 163 adults and three children had made it on board, including 34 journalists, four newsreel movie men, and two squirrels sent by a prankster to travel with the “nuts.” They were promptly christened William Jennings Bryan and Henry Ford.

Making the trip with the people and animals, the Oscar II was outfitted with 20,000 envelopes, 1,778 pencils, 30,000 staples, 5 gross of erasers, 36 jars of paste, and 240 boxes of carbon paper. In addition, the Oscar II had on board a radio, which Ford used extensively to broadcast his message of peace to anyone who would listen.

Rosika set herself up as the queen of the ship. She rarely mingled with the other delegates, and when she did it was only to give “advice,” which she expected to be obeyed without question. She attempted to control every aspect of shipboard life, including access to communications with the outside world, something that didn’t endear her to the journalists who were along for the ride primarily to chronicle the missteps of the Peace Mission.

The first shipboard fight occurred on the eighth day at sea. On December 12, President Woodrow Wilson, who had stayed clear of the Peace Mission, delivered his “preparedness” speech to the Congress, in which he advocated a strengthened navy and army “sufficient to play its part with energy, safety, and assured success.” To the passengers of the Oscar II that meant that Wilson was getting the United States prepared for war.

The delegation split on how to respond to Wilson’s new stance. Rosika and Lochner were ready to demand that those who didn’t sign a declaration condemning Wilson’s position could leave the ship at the next port. In the end, only 35 members signed the pledge against Wilson’s speech, but it divided the delegation for the remainder of its mission.

Touring the Neutral Countries

Touring the “neutral countries” of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark before pushing on to The Hague was entirely Rosika’s idea. Calling the arrival of the Peace Mission in Europe would be “…recorded as one of the most benevolent things the American Republic ever did,” Rosika promised grand receptions wherever the delegation went. The first stop on the European tour was Norway.

Schwimmer predicted a big welcome in Christiania (now called Oslo). But when the Oscar II docked at 5 a.m. on a bitterly cold Sunday morning they found no welcoming committee. About four hours later a dozen people showed up at the pier, but they paid the Peace Mission’s arrival no mind.

The lack of interest in their arrival didn’t deter the delegates from assuming the role of tourists. Beginning with charting a train to a local ski resort, by the end of their Christmas binge they managed to spend $56,000 of Ford’s money.

Everybody was enjoying themselves except for Ford himself. Almost being washed overboard during the crossing had put Ford in bed with a mild case of the flu. When he arrived in Oslo, his insistence on walking to the hotel, and later a hike through mountain snow, put Ford back in bed with a relapse.

Ford’s illness kept him from participating in any of the scheduled peace meetings and dinners the delegates had arranged. He did finally consent to meet a group of Norwegian businessmen but talked more about how his tractors could stop the war by putting men to work than the efforts of the Peace Mission.

Whether it was his illness, his beginning to lose interest in the endeavor, or for some other reason not clear, Ford decided that he had had enough. “Guess I had better go home to mother,” he said. “I told her I’ll be back soon. When some of the delegates heard of his decision they begged him to stay. He initially relented and promised to go onto Stockholm, but checked out of the hotel at 2 a.m. on Christmas Eve, making his way to Bergen to board the SS Bergensfjord for the trip home. The rest of the delegation, most of whom were unaware that Ford had left, boarded a train going in the opposite direction for the 20-hour ride to Stockholm.

In Sweden, they were welcomed with open arms. Hailed as “modern descendants of the Vikings,” they were so popular in Stockholm that they decided to spend an extra week sightseeing and spending more of Ford’s money, including donating $11,000 to the city’s poor, almost $3,000 to various Swedish peace organizations, and a silver service to Mayor Lindhagen. When they finally decided to leave, 1,500 Swedes came out to see them off, as they made their way to Copenhagen, Denmark.

The Danish leg proved to be the most successful of all. The Danish neutrality laws against public meetings worked in their favor, in that they by necessity promoted more one-on-one meetings, and as long as a gathering was classified as “private” (meaning by invitation only), they were free to conduct their business.

On January 7h, the Peace Expedition left Denmark for the final leg of their trip to The Hague, by traveling to Holland through Germany. The German transit agreement didn’t allow the delegates to touch German soil; eventually, the delegates were allowed to complete the last leg of their journey by crossing Germany in a sealed train under armed “escort.”

At The Hague

The delegates arrived in Holland on January 8h, having been on the road for three weeks. For some it was the end of the road; the students were sent home three days later. For others, it was the beginning of the work that they had been planning, specifically to promote their conference and elect delegates before their scheduled departure on the fifteenth. The main goal was to convince the Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, and Dutch delegations (some of whom had traveled with them to The Hague) to select permanent officials for their planned Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation.

But the Americans had arrived to a crowded place, as 57 other peace groups had already set up shop at The Hague. Coupled with Rosika’s bad reputation (which had preceded her), her bad attitude towards other peace groups, and the absence of their only celebrity Mr. Ford, by the time the Americans had elected their representatives to their conference they still hadn’t attracted a Dutch delegation.

Ford arrived back in New York on January 3 and immediately did two things. The first is that he denied abandoning the peace mission or conceding that it was a failure, declaring:

“If we can shorten this war by even a single day we will have saved as many men as one employed in our factory turning out 2,000 cars a day. And I believe that the sentiment we have aroused by making the people think will shorten the war. When you get people thinking, they will think right.” --Henry Ford

The second thing he did was to turn over the project to his private secretary Ernest Liebold, who almost immediately began his efforts to close the peace mission down.

Back at The Hague, those Americans not selected to be a delegate sailed for home on January 16, six weeks after leaving New York. Three weeks later the remaining delegation, such as it was, headed back to Stockholm to begin their conference.

The Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation

The delegates returned to Stockholm and on February 28, 1916, began their conference. But with no acknowledged leader, the delegates were often distracted and off message. Rosika didn’t help the peace effort she had long championed; within two weeks her overbearing attitude had succeeded in alienating many in both the American and foreign delegations.

Rosika eventually resigned from the conference, gambling that Ford would intervene and put her back in charge. But Ford had been kept informed of Rosika’s bad behavior and readily accepted her resignation when it reached him in Dearborn. She remained in Stockholm trying to influence events from the sidelines, but Ms. Schwimmer’s active involvement in the Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation was over.

The Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation, which had begun in February, was disbanded on April 20. At the cost of $30,000 a month (again, Ford’s money), they succeeded in producing a draft resolution that was sent to each warring country.

None ever replied.

Afterwards

With Wilson in December of 1916 finally taking an interest in negotiating an end to the war, Ford lost what little remaining interest he had in the peace movement. Summoning Lochner to Dearborn on February 7, Ford informed him of his decision to cease all peace activities by the first of March.

President Wilson’s peace efforts ultimately proved unsuccessful; on February 1 Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare against both neutral and enemy shipping. The United States broke diplomatic relations two days later.

The disclosure of the Zimmerman Telegram (in which Germany tried to persuade Mexico to enter the war) was the final straw; the US entered the war on April 6, 1917.

Henry Ford returned to making his Model Ts, and when the United States declared war Ford converted his plants from making cars to support the war effort. Ford justified his decision by declaring that when the country entered the war “… it became the duty of every citizen to do his utmost toward seeing through to the end that which he had undertaken.” He promised publicly never to make a dime on the war and returned $130,000 (of the estimated $925,000 he actually made) to the government.

This, of course, didn’t sit well with his former pacifist friends. One former member of the Peace Mission took Ford to task, saying:

“One cannot escape the conclusion that Ford himself never fully grasped the idea that he championed, and that his peace campaign…was merely the passing whim of a man who, elated by his successes as an inventor and manufacturer, went far beyond his depth when dabbing in statesmanship.”

Ford ran for the Senate in 1917, barely losing. He retired from Ford Motors in 1938 at age 75, but in returned in 1943 when his son Edsel died. He retired again two years later when his grandson Henry Ford II took over the company.

Henry Ford died at his home in Dearborn, Michigan on April 7, 1947. He was 83 years old.

It was said that Rosika Schwimmer suffered a nervous breakout and checked herself into a sanatorium. Eventually, she made it back to her native Hungary where she was appointed minister to Switzerland, becoming the first female ambassador in history. After Hungary fell to the Communists in February 1920 she was smuggled to the United States. Arriving in August of 1921, she applied for citizenship, but her pacifistic views did not make her a popular figure. It took two years for the case to reach the Supreme Court, which ruled against her 6–3 in June 1929.

Rosika spent the rest of her life in New York City pursuing her pacific causes. She died on August 3rd, 1948 of pneumonia.

The Oscar II was sold to the Japanese as scrap in the 1930s.

Sources:

Burnet Hershey. The Odyssey of Henry Ford and the Great Peace Ship.

Barbara S. Kraft. The Peace Ship: Henry Ford’s Pacifist Adventure in the First World War.

About the Creator

Randall G Griffin

I am Pop-Pop, dad, husband, coffee-addict, and for 25 years a technical writer. My goal is to write something that somebody would want to read.

Comments (2)

Thanks, I appreciate your comment.

This article is fantastic—I appreciate its well-crafted and informative nature.