"Through the Looking Glass", by Lewis Carroll

A classic book for children

My early childhood was spent during the 1950s, and I was lucky to have a father who knew his way around books and stories and did everything he could to interest me in the literature that he had enjoyed when he was much younger. However, the considerable age gap between us (he had been born in 1906) meant that the stories he introduced me to came from a much earlier age. I therefore heard and read many stories that had been written prior to World War I!

That is not to say that many of these were not classics that have continued to be popular right down to the present day, and it is one of these that I am going to focus on here.

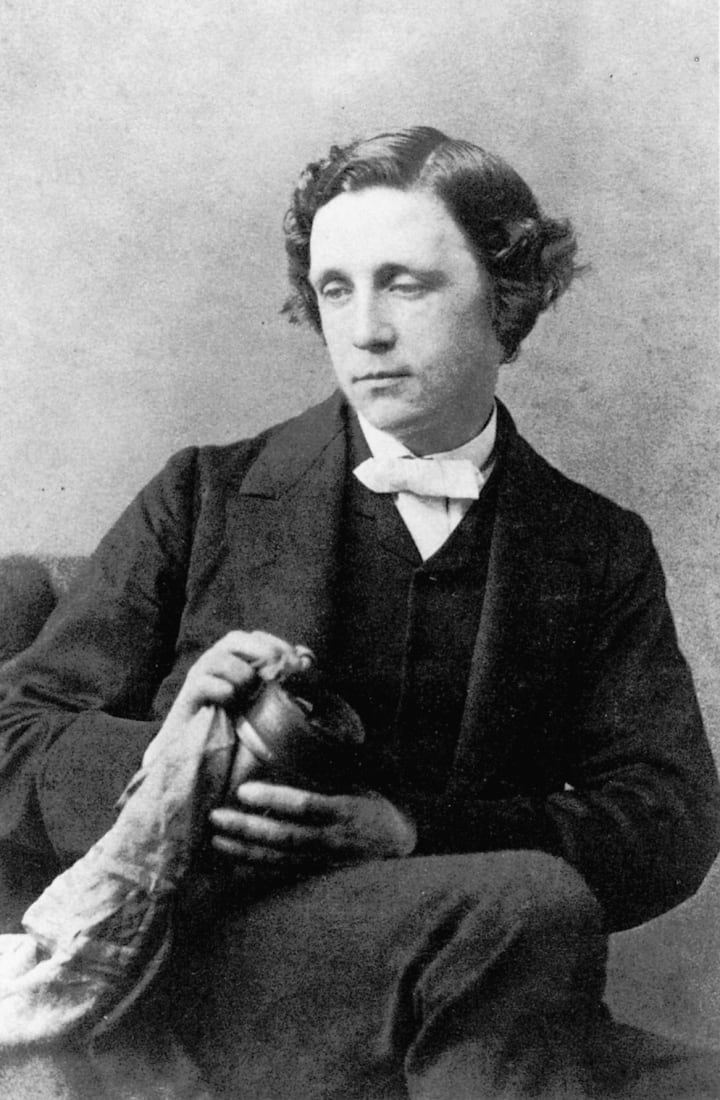

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-98), who wrote under the pen name Lewis Carroll, is probably best known for his timeless “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, which was published in 1865, but I have personally gained more pleasure from the sequel that appeared in 1871, namely “Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There”. Despite the wealth of fantasy characters and silly situations that both Alice books present, “Looking Glass” has never been as popular as “Wonderland”, having had relatively few movie and TV versions made of it.

The two books have a similar structure, in that in both of them Alice moves through a fantasy world and meets a succession of highly eccentric characters, but “Looking Glass” has an extra dimension, this being that it is based on a game of chess. Alice is the White Queen’s pawn, and her task is to move all the way from the second row of the virtual chessboard to the eighth, where she will be crowned as an extra Queen and checkmate the Red King.

It is perfectly possibly to enjoy the book without knowing anything about the rules of chess, because the moves are disguised in the interactions between the characters, but Carroll took pains to point out – in a Preface that was added to a later edition – that the moves “will be found, by anyone who will take the trouble to set the pieces and play the moves as directed, to be strictly in accordance with the laws of the game.”

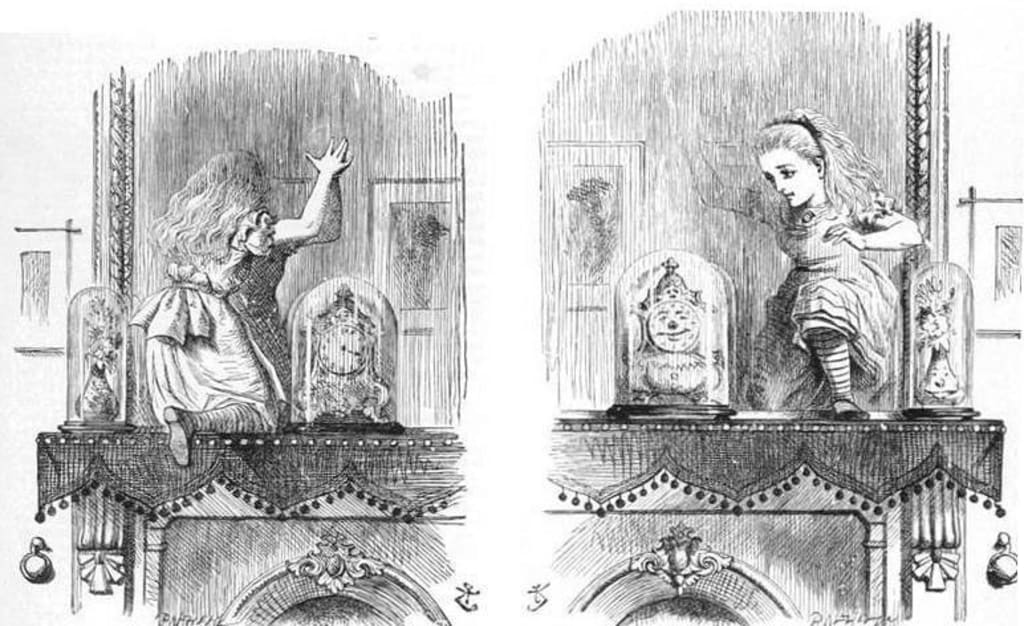

The story begins with Alice talking to her cat and two kittens, which leads to her mentioning chess and wondering whether her black kitten looks like the red queen on her chessboard – the use of red and white for chess pieces, as opposed to black and white, was common in Victorian times. She then starts wondering about the room she can see in the large mirror (or looking glass) over the fireplace. This must be “Looking-glass House”, which looks just like her own home, but with everything in reverse. Alice wonders about the things she cannot see, such as whether there is a fire in the fireplace, and then she finds herself standing on the mantlepiece and walking through into Looking-glass House.

It is only at the end of the story that we learn that Alice has dreamt the whole adventure, so it must be just before she goes through the looking-glass that she has fallen asleep in her chair.

Once she is in the “other room”, she begins to find that this world is very strange indeed, such as the chess pieces that are walking around on the floor and conversing with each other. She also finds a poem in a book on the table, but it is only when she holds it up to the looking-glass that she can read it, because it is printed in “mirror writing”.

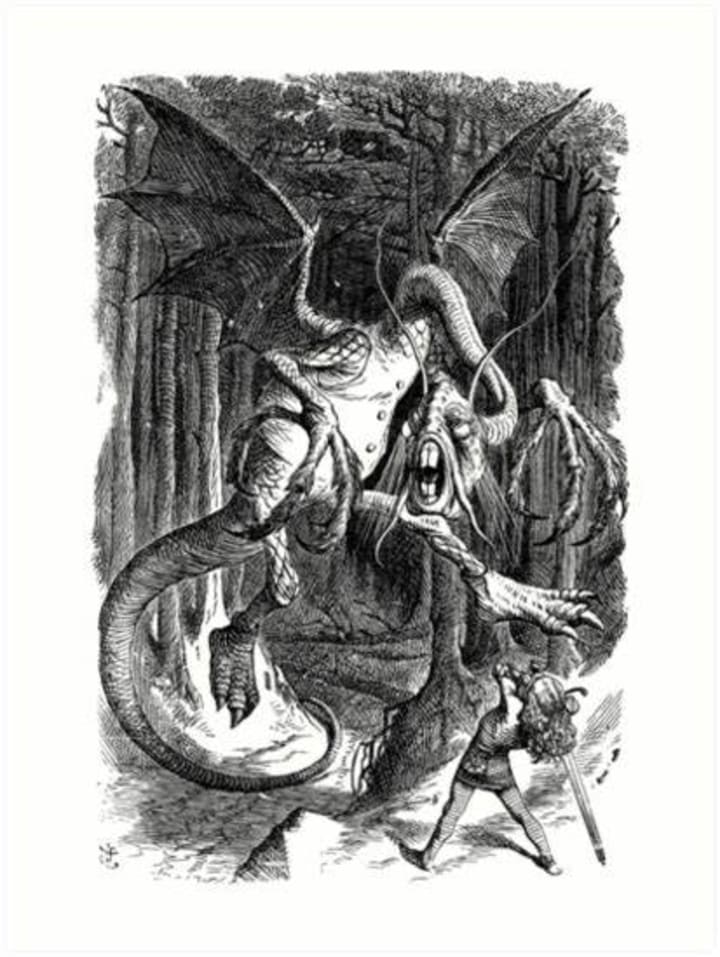

This poem is “Jabberwocky”, which is one of the most celebrated nonsense poems in the English language. It is full of words that Carroll invented, but which he intended to mean something! Later in the book, when Alice meets Humpty Dumpty, she asks him to explain the poem, which he is happy to do.

Alice floats out of the house into the garden, where the flowers talk to her, then meets the Red Queen, who invites her to be the White Queen’s Pawn in the game of chess to be played on the huge chessboard that Alice can see from the top of a small hill. The Red Queen explains how the game will be played, with Alice starting in the second square then advancing to the fourth, as pawns can do on their first move and which Alice does by catching a train.

On her journey down the chessboard, Alice meets several nursery rhyme characters - Tweedledum and Tweedledee, the Lion and the Unicorn, and Humpty Dumpty. Apart from the Royal characters and the Red and White Knights, there are no other characters that relate directly to chess pieces.

Every encounter Alice has is an opportunity for conversation that makes sense and nonsense at the same time. Much of this comes from plays on words and twisted language that is highly inventive and – even given the passage of time since the book was written – very funny to read or listen to. It is true that not every quip and witticism works today, and some of the references will be lost on a modern child, but there is still plenty that is guaranteed to raise smiles.

There are also many quotable lines, including some that are often heard today as figures of speech. One of these is the White Queen’s dictum that you can have “jam tomorrow and jam yesterday, but never jam today”.

A feature that Carroll continued from “Wonderland” to “Looking Glass” was the inclusion of nonsense poems, many of which took the form of parodies of poems that children of his time would have known from having to learn them at school. In “Looking Glass”, for example, the White Knight recites “Haddock’s Eyes”, which is a parody of a poem by William Wordsworth ("Resolution and Independence") that was far better known in Carroll’s day than it is now.

Apart from “Jabberwocky”, the best-known poem from “Looking Glass” is the long poem recited by Tweedledee, namely “The Walrus and the Carpenter”, which is not a parody of anything. It is a nonsense poem that has achieved a life outside the book, for lines such as: “The time has come, the Walrus said, to talk of many things: Of shoes, and ships, and sealing -wax – Of cabbages and kings”.

The use of poems in “Looking Glass” has served many generations of children as an introduction to poetry, and to the idea than poetry can be fun. If older people want to seek for symbols and hidden meanings, then these poems provide ample scope for that.

Mention must also be made of the illustrations created for “Through the Looking Glass” by John Tenniel (1820-1914), who had also illustrated “Wonderland”. His highly-detailed line drawings dovetailed perfectly with Carrolls’s text by bringing out all the features of the characters that the author had intended, and even adding a few more. Tenniel was even responsible for some changes to the text, most notably when he complained to Carroll that a scene involving “a wasp in a wig” did not interest him in terms of illustration, so it was left out of the book.

Carroll ended later editions of the book with a poem, upon which huge significance has been placed by later readers. This is a wistful little piece, clearly written long after the main story, that is a tribute to the real Alice, Alice Liddell, for whom this story and Wonderland were written, although she was long past her childhood when “Looking Glass” was published. The poem is an acrostic, with the first letter of each line spelling out her full name – Alice Pleasance Liddell. It includes the lines “Still she haunts me, phantomwise, Alice moving under skies, Never seen by waking eyes”, which do nothing to counter suggestions that she meant more to the author than a child to whom he could tell stories (and take many photographs of, which Charles Dodgson famously did).

Whatever the truth of the matter as regards the relationship between Alice and Lewis Carroll, it is quite clear from reading both books that the author had a real understanding of how a child’s mind worked, and how unusual situations might be responded to by someone of the age of the Alice of the books, given their education and background.

“Through the Looking Glass”, as well as being a classic book of the nonsense genre, is also a statement about how important it is for a child not to be forced to grow up too quickly. As the final poem states, the book lives on because it allows children to go on “Dreaming as the days go by, Dreaming as the summers die” and the final line says it all: “Life, what is it but a dream?”

About the Creator

John Welford

I am a retired librarian, having spent most of my career in academic and industrial libraries.

I write on a number of subjects and also write stories as a member of the "Hinckley Scribblers".

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.