he Western was for several decades the film genre that defined masculinity. It was where the silhouettes of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood became inscribed in cultural history, framed by legendary directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. In reality, cowboys were overworked, underfed and underpaid, but in cinema they could be tough, independent wanderers who chose the freedom of the wilderness over the confines of domesticity. And though the Western itself has been declared dead many times over, it always picks itself up off the dusty ground, ready for one more showdown. Even now, perhaps only the superhero could threaten the cowboy as film's ultimate symbol of all-American manhood.

But what happens when a woman steps behind the camera? From Kelly Reichardt's Meek's Cutoff and First Cow, to Chloé Zhao's The Rider and now Jane Campion's awards-tipped The Power of the Dog, women directors in the 21st Century are using the Western to unravel traditional representations of gender. As Helen O'Hara, author of Women vs Hollywood, tells BBC Culture: "These female-made Westerns are really tackling toxic masculinity and the ways in which men's attempts to prove themselves as men can backfire, rather than glorifying the myth of the cowboy as the older, traditional Western did."

Campion's The Power of The Dog, an adaptation of Thomas Savage's 1967 novel, is set in 1920s Montana, and follows prosperous cattle ranchers Phil Burbank and younger brother George. Devilishly clever, charismatic and cruel, Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch) is an imposing figure, and his soft-hearted, taciturn brother (Jesse Plemons) is the primary target for his bullying. But when George marries struggling widow Rose (Kirsten Dunst), bringing her delicate, artistic teenage son Peter (Kodi Smitt-McPhee) into the family, Phil is incensed.

Story continues below

Gender relations are never straightforward in Campion's films, and her male characters tend to be threatening yet fascinating – Professor Duncan Petrie

At first glance, Phil belongs in a traditional Western. He has the swagger of an alpha male; dirty and rough-shaven, clad in brown woollen chaps that give him animalistic bulk. When he first strides into view, Campion shows his lone figure framed by a window, evoking the iconic final shot of John Wayne in The Searchers (1956). Phil despises anything feminine, preying on his new sister-in-law and her lisping son, who crafts elaborate paper flowers in his bedroom. The only time Phil betrays any affection is when he tells reverent stories about his old mentor, the late Bronco Henry. And yet beneath this facade is someone raw and vulnerable. He and George still share their childhood bedroom, and Phil never undresses inside, only bathing in an isolated clearing. When Rose invades his tightly controlled world with her feminine presence, Phil embarks on a campaign of psychological torture against Rose that eventually transforms into a fixation on Peter.

What rises to the surface – an undercurrent in the novel but made overt by Campion – is Phil's repressed homosexuality. In part, Bronco Henry represents the lost myth of the West. But, as Annie Proulx, author of Brokeback Mountain, observes in the afterword of the novel's reissue: "Bronco Henry has a tremendous emotional grip on Phil’s bitter and loveless heart," suggesting that he desired, if not loved him. That forbidden desire is rekindled as Phil tries to mould the effeminate Peter into a version of himself, the perfect cowboy.

Transgressive eroticism is hardly new territory for Campion, as Professor Duncan Petrie, head of film at the University of York, tells BBC Culture: "Gender relations are never straightforward in her films, and her male characters tend to be threatening yet fascinating. She's also very much a Freudian filmmaker, exploring the repressed finally being released." And although The Power of the Dog is a departure for Campion – it's the first of her projects to foreground a male protagonist – it's hardly surprising that she was drawn to a character as complex and unconventional as Phil.

Reframing the cowboy

The Power of the Dog is a portrait of a man who represses his true identity, consumed by his own self-loathing, and undone by his doomed attempts to embody the cowboy ideal. But what precisely is the role that Phil is failing to play?

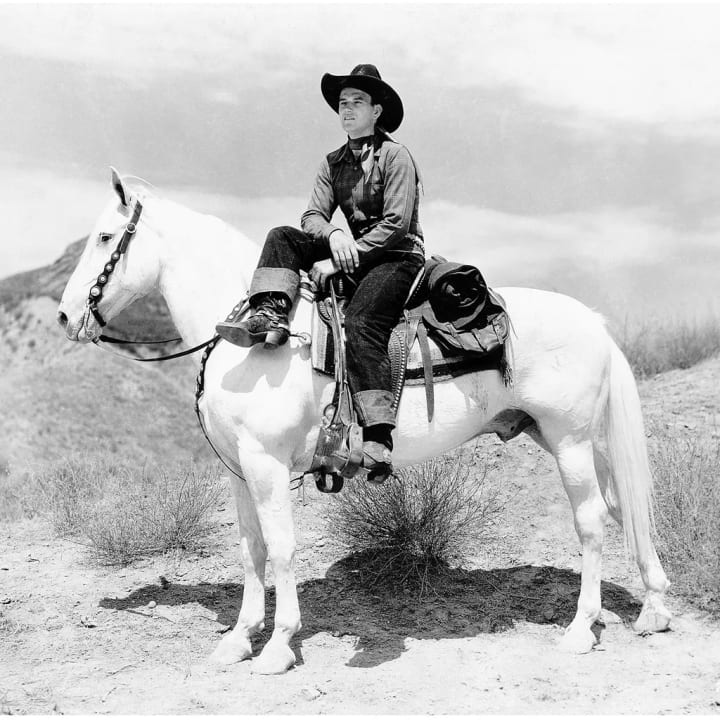

In his book Westerns: Making the Man in Fiction and in Film, Lee Clark Mitchell argues that at the heart of all Westerns is "what it means to be a man, as ageing victim of progress, embodiment of honour, champion of justice in an unjust world." Even today, the cowboy is still a mythic figure. The Western heroes of the 1930s and 1940s like the Lone Ranger and Roy Rogers stood for decency and family values, standing up for the innocent against black-hatted villains. They were also entrusted with defending their frontier against Native Americans, who were portrayed either as dehumanised savages or degradingly subservient. Never succumbing to any kind of emotional vulnerability, characters like the ones played by John Wayne were physically imposing, reserved but aggressive at the right time, and fiercely protective of America as an individualistic, conservative, white nation.

Eventually, these classical Westerns were broadly replaced by the more morally ambiguous and stylistically adventurous Westerns of the mid-to-late-1960s and 70s, reflecting a period of political unease. Films such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Wild Bunch, both released in 1969, and Spaghetti Westerns like A Fistful of Dollars (1964), undercut the idealistic vision of the West with their nihilistic antiheroes. These films were subversive in their lack of patriotism but were often intensely misogynistic. There were some Westerns that didn't play by these rules, like Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954), featuring Joan Crawford as a saloonkeeper who quite literally wears the trousers, and the cross-dressing, queer-coded adventures of Doris Day in Calamity Jane (1953). But for the most part, the Western was both about and authored by men. And while partnerships between men were celebrated, any sexuality was purely subtextual. The gay cowboy is certainly a fetishised figure in pornography and sometimes crosses over into the mainstream in films like Midnight Cowboy (1969), My Own Private Idaho (1991) and, of course, Brokeback Mountain (2005), but these are rare examples, and arguably only Brokeback Mountain is anything close to a real Western.

Taking on the Old West

The emergence of several Westerns over the past decade by women directors might seem like a new phenomenon. But, as Shelley Cobb, associate professor of film at the University of Southampton tells BBC Culture, "Women have been writing and directing Westerns since the beginning of cinema. In the early decades [silent film director] Lois Weber is known to have made two, now lost, and Anita Loos wrote at least one. They are few and far between, but not unheard of."

One milestone was 1968's The Belle Starr Story. Lina Wertmüller was brought in at the last minute on this extra-cheesy Spaghetti Western, which she co-directed under a male pseudonym. Nine years later, Wertmüller would become the first woman to be nominated for the best director Academy Award for Seven Beauties. But The Belle Starr Story was hardly a feminist triumph, with its dubious sexual politics and sleazy soft-porn aesthetic. It wasn't until 1993 that another female director would venture out into the Wild West, this time much more boldly. Maggie Greenwald's The Ballad of Little Jo tells the story of Josephine Monaghan (Suzy Amis), who is driven out of her home for having a baby out of wedlock and forced to make her own way in an unforgiving world. After she escapes being sexually assaulted, she swaps her dress for men's clothes, cuts her hair and takes on the masculine persona of "Jo". Unlike Calamity Jane, whose cross-dressing is an amusing eccentricity that she eventually abandons to get married, Josephine lives as Jo until their dying day. Unfortunately, perhaps because of its radical presentation of gender nonconformity as empowering, The Ballad of Little Jo didn't have a major impact on culture.

It took 17 more years before another woman director emerged who was interested in taking on the Old West. Kelly Reichardt's Meek's Cutoff (2010) follows three couples attempting to cross the desert on the Oregon Trail in 1845, guided by the proud and foolish Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood). Reichardt upends the traditional Western not only by adopting a slow, doom-laden pace, but also by focusing on the three women on the trail: Emily (Michelle Williams), Glory (Shirley Henderson), and Millie (Zoe Kazan), and their unending domestic tasks. Like the three wives, the audience is shut out of any decision-making, highlighting just how little agency women had in the 19th Century, while the men are presented as foolish, paranoid and desperate. By rewriting the patriotic myth of the frontier as a desperate scramble for colonised land, Reichardt undercuts the kind of nostalgia often peddled by the genre.

It's encouraging that women are breaking into genres previously dominated by men – Helen O'Hara

Reichardt returned to the theme of masculinity in the Western with First Cow (2021), but this time she disrupted it with two gentle, compassionate and affectionate male characters. Cookie (John Magaro), a forager and cook for a party of fur trappers, and King-Lu (Orion Lee), a Chinese immigrant, are bonded by their outcast status and set up house together in the woods. They become thieves but they don't rob banks or stagecoaches; they only steal milk from the wealthy landowner's cow to bake and sell their own cakes. First Cow might take place on the 19th-Century frontier, but it's an extraordinarily tender antidote to the Western's typically aggressive, regressive, portrayals of masculinity, and a reflection of the US as a capitalist society. "That's there throughout all [my] films," Reichardt told Sight and Sound: "The question of society, and who we are to each other, and what our obligations are. It's that idea in the American outlook: 'We're all in it together' versus 'each man for himself'."

Chloé Zhao, like Reichardt, tells resonant stories about US society, capturing contemporary America through a Western lens in her first three films. Songs My Brothers Taught Me (2015), The Rider (2017), and 2021's best picture Oscar-winner Nomadland each focus on a different character living on the margins of society: a girl growing up on a Native American reservation; a young rodeo rider searching for his identity after a life-changing accident; and an impoverished widow living in a camper van.

The Rider's Brady (Brady Jandreau) might look the part, but he is a gentler, more emotive cowboy. Zhao repeatedly shows him as both a breadwinner and a caregiver; whether for his younger sister with special needs, his friend Lane who is paralysed, or the horses he lovingly trains. His lack of embarrassment at displaying affection, whether verbally or physically, demonstrates that he is not as repressed or withdrawn as more traditional Western heroes, or The Power of the Dog's Phil Burbank. He is also permitted to cry; breaking down in tears after the realisation that the seizures he's experiencing in his hand will prevent him from riding, the one thing that grants him a sense of freedom from a lifetime of poverty and deprivation. At the climax of the film, Brady is warned by his father not to take part in another rodeo for fear of incurring another injury. Brady lashes out in anger: "What happened to 'cowboy up, grit your teeth, be a man'?!" Zhao might as well be asking what it means to be a man today.

Gender is not the only lens through which the Western is being reimagined by contemporary filmmakers. Two Westerns with almost entirely black casts were released in 2021: The Harder They Fall, which starred Regina King, and Concrete Cowboy, starring Idris Elba. The black Western has been around since the 1930s at least, but it's revealing that this subgenre is also resurfacing. Petrie describes the Western as "an attempt to redeem an irredeemable colonial project", and these films are certainly in conversation with the US and its dark post-colonial legacy, which has only become more relevant in the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. If the Western once existed as an attempt to justify the suppression of Native American culture and civilisation, then perhaps it can only continue to exist if it acknowledges the echoes of the US's colonial history. To reimagine the quintessential American genre, one which is built upon white supremacy, is to question the status quo.

O'Hara is cautiously optimistic about what this upending of the genre means: "It's a bit too early to say that these films are a trend, but it's encouraging that women are breaking into genres previously dominated by men." Cobb is less hopeful, however. "Cinema goes through these periods when gender equality is circulating in mainstream discourse and women's stories get centred and women are put in the centre of what are usually considered masculine or male genres. But as cinema history and history generally makes clear is that this is often a 'two steps forward and one step back' or sometimes even 'two steps back' cycle."

Whether or not this particular trend endures, however, it's fascinating to witness what might be the beginning of a shift, a dismantling of this most enduring of American cultural myths. Directors like Jane Campion, Kelly Reichardt and Chloé Zhao are reinventing the cowboy legacy handed down by male directors over the past century, creating work that is bold and challenging. The Power of the Dog's rigid and repressed Phil Burbank is ultimately a tragic figure, but in his turmoil we see a reflection of attitudes that may be disappearing into the past.

About the Creator

Monu Ella

And I know it's long gone and there was nothing else I could do

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.