The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Origins of Fantasy

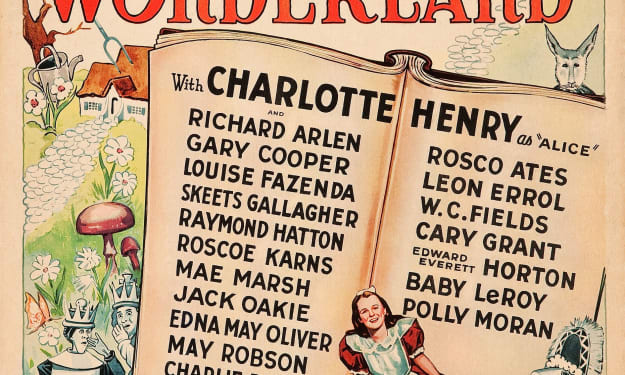

Two weeks ago, we started our journey through the land of Fantasy by examining one of the earliest examples of Fantasy in film, 1933's Alice in Wonderland. This week, as promised, we begin our literary survey with the great great granddaddy of all fantasy epics, hero journeys, and quest sagas, The Epic of Gilgamesh. It's the oldest known literary work of note in the world. That means (yes, you know it!) that Fantasy was the first fiction genre in publishing.

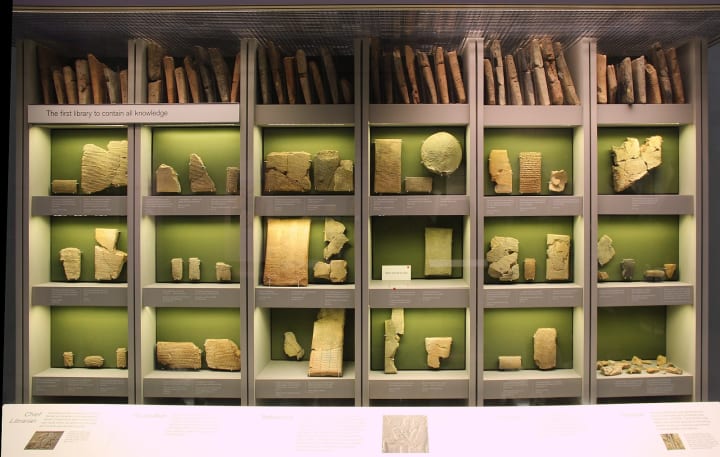

Pre-dating The Bible by 600 years, The Iliad, The Odyssey, and other greek myths by more than a thousand years, the work has fascinated scholars in literature and history since its discovery amongst a treasure trove of 30,000 cuniform tablets in what was once the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh (modern-day Mosul, Iraq). This vast collection of early documentation, once the collection of the last great king of Assyria, Ashurbanipal, was compiled at his behest. He instructed cities and centers throughout Mesopotamia to send copies of all written work in their respective regions to be amassed in his library. This grand collection contained governmental, legal, and financial works as well as incantations, hymns, and scientific works. Amongst this myriad of texts, researchers discovered the first written epics, ten epics in all: The Epic of Gilgamesh, Enūma Eliš, the myth of Adapa, and the Poor Man of Nippur amongst them.

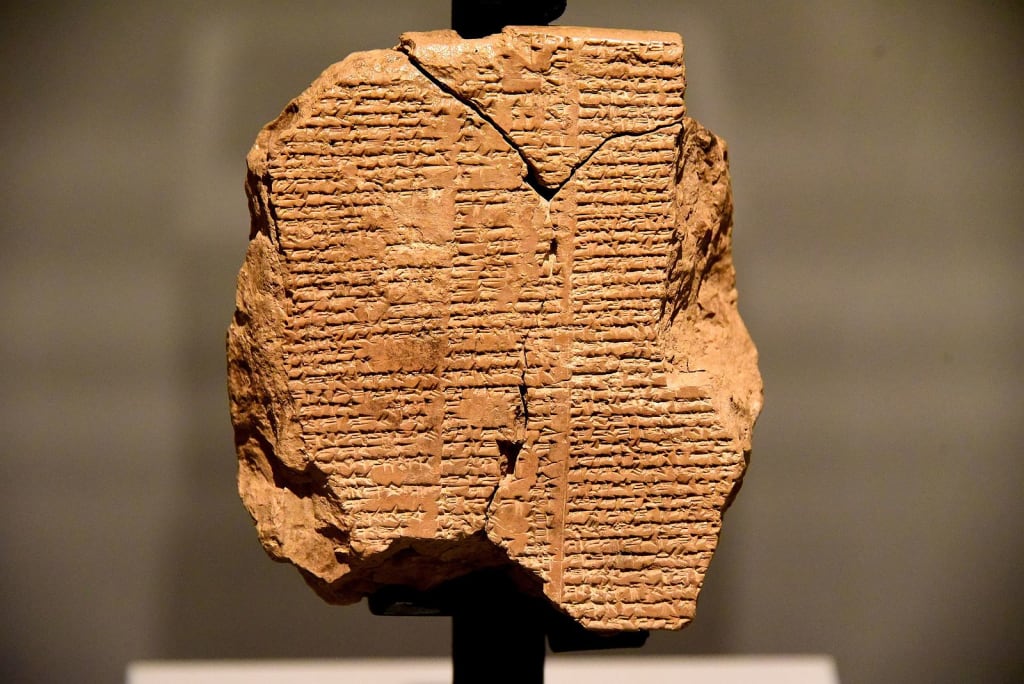

The Epic of Gilgamesh as we know it today was not originally a single story but five separate Sumerian poems (portions dating back as far as 2100 BCE) later pieced together for a combined version in Akkadian. This connected narrative, in turn, had at least two different versions known as the "Old Babylonian" and, later, the "Standard Babylonian." Both of these works are sadly incomplete, with portions lost to history, yet it is from these two works that we can reconstruct many of today's translations.

Since this is a translated work, finding versions that are true to the original and easy enough to read can sometimes be challenging. Since we started this series, we vowed to look at formats easily obtainable by the general public. While the Andrew George version is considered the definitive academic version, we chose the more controversial but accessible Stephen Mitchell work. This choice is primarily due to the readability of the poem in modern English while holding to the form of the original narrative.

Fantasy readers of today will find the story's structure somewhat strange, especially since there is no definitive good vs. evil theme. The character of Gilgamesh seems more like the social media stars of today in that he is concerned primarily with his fame rather than vanquishing evil from the land or contributing to the greater good. In fact, when we first meet Gilgamesh, we see that shoddy temperament on full display in the form of the horrible dictator king he has become. He oppresses his people quite severely and is responsible for heinous acts, such as requiring all maidens to yield themselves to him on their wedding night before being with their groom. Definitely not a hero archetype that I can admire. But Gilgamesh is indeed a powerful being; he is two-thirds god and one-third man with legs, purported to be nine feet long and physical strength equaled by none. No mere mortal could stop him. The subjects of Uruk are left with no choice but to appeal to the gods for intervention, and in a fashion typical for Gods, they decide not to act directly. Instead, they determine what is needed is an equal persona to Gilgamesh, and through this intermediary, Gilgamesh will learn moderation.

Aruru, the goddess of nurturing and fertility, the mother of humankind, creates Gilgamesh's foil, Enkidu, from nothing, a new first man. Enkidu is a wild hairy thing of nature running with the deer and other animals and dwelling in the forest, but equal in strength to Gilgamesh. The remainder of the saga chronicles the journeys of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, ultimately culminating in a hopeless trek through the underworld in a futile attempt to save Enkidu from death's hand.

So while the epic chronicles the usual hero versus monster confrontations, The Epic of Gilgamesh differs from what we've learned to expect from such sagas as Beowulf. Gilgamesh brings disaster to his newfound friend through his destructive actions on the pair's first adventure, a campaign against the guardian of the cedar forest Humbaba. Humbaba is an innocent bystander who has effectively done no harm to anyone other than those who would enter the forbidden forest. Shamash, the god of justice, aids Gilgamesh in the battle by binding Humbaba with the winds. Once defeated, Gilgamesh refuses the creature's pleas for mercy, instead choosing to kill him to secure his own fame. This a specious claim, if there ever was one, since Gilgamesh persecuted the innocent creature, had an unfair advantage in the fight itself and ultimately behaved despicably by murdering Humbaba. This could be an early parable about man's war against nature and his own selfish self-interest. This terrible act sets off a series of events, ultimately resulting in Enkidu being marked for death by the Gods.

Additionally, the epic is historically fascinating, with an odd relationship to the bible. The text actually created much controversy in its early translations. Since the text contains an alternate version of the genesis flood narrative that matches the new testament version nearly point for point. Rabbinical and biblical scholars took the position that both the epic and Torah took the story from a "common tradition" in the region. It could mean many other things with the considerable timespan between one and the other, but we won't speculate.

Yet one can't help but notice other biblical similarities, such as how Gilgamesh uses the Temple Priestess Shamat to lure Enkidu out of his pure natural state through the knowledge of sex (or sin) and mankind's ways to include food (an apple?). Once educated, Enkidu cannot return to his previous state in nature (Eden). Other biblical phrases also seem to be directly lifted from Gilgamesh, such as "a triple-stranded rope is not easily broken." The parallels don't stop there with relationships between the Book of Enoch and the tale of Humbaba via a third work, The Book of Giants, and the story of Jacob and Esau closely resembling the wrestling match between Enkidu and Gilgamesh when they first meet.

As the predecessor to every other known piece of literature, its impact on Fantasy is felt throughout its entirety. We touched briefly on its relationship to the bible; scholars have argued that the tale also reached ancient Greece, influencing the stories of Heracles, The Iliad, and the Odyssey in form and substance. As such, no self-respecting Fantasy fan should not do without this relatively quick reading to round out their knowledge of the genre. Fantasy, after all, is probably the richest of all genres, with backstories, history, technique, and tradition.

Our recommended version for this is Gilgamesh: A New English Version, and it can be found on Audible, Amazon, and other bookstore outlets. Next week we'll look at Death Takes a Holiday (1934), a Hollywood incarnation of the aspect of death.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.