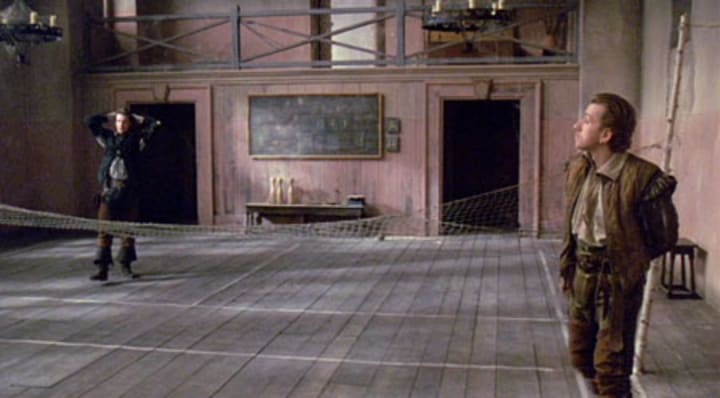

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead

~ essay on Hamlet and Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead (1990) and the life of the “NPC.”

~ essay on Hamlet and Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead (1990) and the life of the “NPC.”

Have you heard of the “NPC” meme? NPC as in “non-playable character.” The term comes from video games, to describe all of the characters (typically) robotically walking and talking around you in the digital environment — all the personas in the game that are not controlled by you, the PC, the “playable character.”

In a video game, NPCs are there to service the narrative either as background imagery to further convince you that this city / fantasy world / dystopian apocalypse, etc. is a real, living breathing world — or as characters for your PC to converse with, bounce exposition off of, receive quests from, f*ck/marry/kill, etc.

Concisely, non-player characters are not in control. They do not have an impact beyond what their assigned limit in the world allows them to have. In writing theory terms, they are rarely three-dimensional characters due to the fact of their non-protagonist status (not true for many modern game NPCs however, especially from BioWare and CD Projekt Red). They are more defined by their appearance than their heart; they may even have a catch phrase they repeat as you pass them by, their sole way of interacting with you or the world, of being remembered by the player.

In sum, the NPC cannot think for themselves — they are programmed in the exact way that the PC is not (in that YOU are controlling the PC and can choose how you wish them to interact with the world.)

The “NPC” meme, as many Internet things do, started on 4chan. The original post formed a theorization of the “NPC” lot in real life, due to a reincarnation-based fixedness in the amount of conscious souls there can be in the world. The leftovers — the real-life NPCs — are these lifeless people we see every day but barely notice, who lack an “inner voice” and just spout out buzzwords and hackneyed arguments they hear from mass media.

Aside from being an arrogant and borderline fascist way of looking at yourself versus the people in the world around you, it was essentially just another shitpost equally targeting SJWs (social justice warriors) and “normies” — i.e. the people who abide by popular culture and who 4chan detests most of all. Regardless of its potentially dehumanizing rhetoric or its bleak reality in our modern world, the idea of the NPC is something that came to mind in a rather visceral way from out of my rewatch of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, the 1967 play/1990 film that follows the absurd travails of the minor duo from Shakepeare’s epic, Hamlet.

The “absurdist, existential tragicomedy” created by Tom Stoppard, R&G Are Dead, as a weird piece of art, is naturally right up my alley. I remembered watching it in high school English, after reading and then watching Hamlet (Kenneth Branagh 1996 version) for the first time. It struck a nerve with its philosophical discussions and absurdist comedy, as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern wander around and try to understand their strange position in the world, unable to recall how they got there or who Hamlet is or what their role is supposed to be. Essentially, R&G is a metafiction about “what if lesser play characters were truly conscious?” — as in not side characters, or NPCs.

What if they did have an “inner voice”? And what if we got to hear it?

What if Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the two old friends called in to spy on Prince Hamlet to determine his malady under order from the King, became wholly aware of their entire lives being manufactured from out of nothingness for a small role in another’s story?

What if a person became aware of the all-encompassing and inescapable nature of fate? / What if a character suddenly understood with certainty that they were, in fact, an NPC?

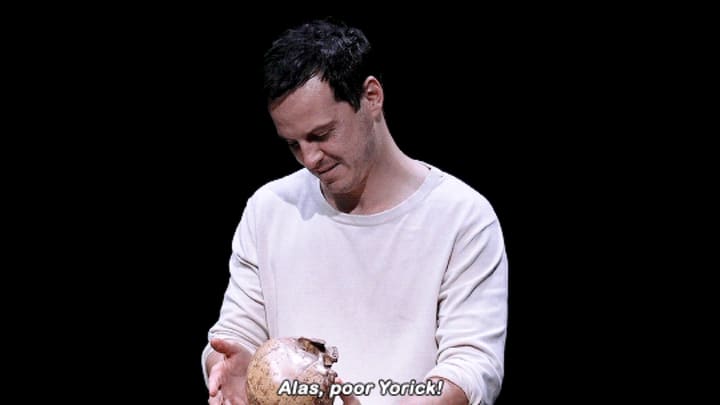

Rewatching the full play of Hamlet now — (Andrew Scott 2018 version) — its brilliance reflects in just how much a singular, mad dream it is. Hamlet is aptly titled, it is a focused venture into the ailing heart and mind of Prince Hamlet. All his fears and desires, the strange turns of his mind’s eye toward existential ponderances to bemused reunions with frenemies to seething rage and suicidal passion, are on beautiful display for the audience. We are inhabiting Hamlet’s exploding mind alongside him — and everyone else is extraneous, confused, muffled. They cannot understand Hamlet’s motivations because they only hear his cutting, half-sincere words, and see glimpses of his behavior and none of his mind.

Why are we here?! How should I continue to be here, suffering the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” when I could just… go? For what should we suffer inevitable betrayal and pain and loss?

I’m less concerned with whether or not Hamlet is a *hero*, or whether his mania reached toward true diagnosable psychosis or not. No matter what, Hamlet’s passionate language and mad action mark him as a legendary literary marvel.

Not so for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

These two are nobodies, a forgotten duo that would be lost to the annals of time, in memory or history. In the original play, they are somewhat comedic roles, with minimal personality or a true arc to their interactions. They are there as an obstacle to Hamlet, yet another quarry for him to jibe with and eventually overcome. They are mildly antagonistic, as passive betrayers of Hamlet’s trust, by agreeing to lie and spy for the King. Though one would say that death is not necessarily what they deserve, it is what Hamlet gives to them by rewriting the letter to the King of England to kill them instead of him, as he escapes back to Denmark and his true fate.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s role in Hamlet is small; not meaningless, but they are basically “NPCs” in form and function.

Showing events from the point of view of two minor characters from Hamlet, men who have no control over their destiny, this film examines fate and asks if we can ever really know what’s going on? Are answers as important as the questions? Will Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (or Guildenstern and Rosencrantz) manage to discover the source of Hamlet’s malaise as requested by the new king? Will the mysterious players who are strolling around the castle reveal the secrets they evidently know? And whose serve is it?

Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead (1990), however, imagines them as real people. Not as PCs, or potential protagonists worthy of their travels in Hamlet’s Denmark together, but as actual persons that have been drawn into a world that they cannot explain nor wield any real control over. Events “play themselves out to aesthetic, moral and logical conclusion,” as the theater troupe Player tells them, and we get to see R and G’s true personas primarily as a response to their liminal environments, a world that is not for them.

From the beginning of the story, with their repeated “heads!” flips of the coin, they are aware of the unreality they inhabit. The impossibility of their personal progress or any true consequential action on their part — outside of their interactions with Hamlet, the King or others of the Danish court, where the *real* action is — is firmly grasped by the duo. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are there for others — and anything they do on their own, away from the spotlight, is a meaningless loop of wasted breath.

“We are spectators” speaks Rosencrantz, or Guildenstern, as their names are mixed up even to them. They’ve been ripped out of bed {non-existence} by “the traveler” {the creator} who they can just barely remember calling upon them to wake up, who gifted them a letter bidding them to Denmark for an unknown yet time sensitive purpose.

How does one go about their life when fate – your next word, your next action, your next scene – has already been revealed and set into motion?

In their travels leading up to the castle and to their scenes with Hamlet, we see R & G flipping coins, chilling quietly in the woods, speaking eloquently on the nature of chance, fate, mortality, playing complex games of rhetoric and discovering physical inventions like the steam engine.

Even without an articulate backgrounding logic {that a real person would have} to their presence in Denmark and in Hamlet’s past, they are able to adroitly discern the reasonability of his ‘madness’ from afar, before speaking to him (and out of the play’s events), just on the facts and circumstances as they hear them {Dead Father + Uncle is New King + who married Queen (Mother) inside of months of the funeral…}.

After speaking to him, they accurately theorycraft on the many plausible reasons for his erratic yet impassioned words and behavior (he wants revenge, he wants to be King, he doesn’t know what he wants… // “Thwarted ambition”, “He’s at the mercy of the elements”, “Half of what he said meant something else, and the other half didn’t mean anything at all…”) And they are angry that they could not have said more, that more of their impressive rhetoric and inquiry was not pressed upon Hamlet; after their scenes from the play, R & G are upset at the limitations of their lines, even as they are disallowed any deviation from them.

In seeing their loping movements through the court together, before, during and after their small slices of true communication with the world {the play Hamlet}, the audience sees that Rosencrantz & Guildenstern carry a kind of linguistic and metaphysical super genius. Not unlike Hamlet, in at least this respect. They can play gorgeous language games; they both have enough of a grasp on the concepts of fate and death and free will to engage satisfying discussions.

R & G aren’t just Hamlet’s conniving yet milquetoast former friends; they are incapacitated strangers, incapable of tapping their full potential, trapped in a world beyond their understanding, sincerely trying — and failing — to decipher why.

To me, the true kernel that presents this absurd duo as “real” people in the story of Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, is not their cleverness, but their fear. Their fear of this strange space they inhabit and its randomness, a place where 100 head flips in a row is commonplace. Their fear of being in a story that they *know* is not theirs. Their fear of potentially dying within it, unable to go back to their own life, a true desire they harbor and speak about away from their *scenes.*

R & G both want to go back home. Whether or not that home exists does not matter. Because they believe it does.

Whether or not their home life is worthy of being known to us in the audience — whether or not Rosencrantz and Guildenstern get up to anything exciting or sexy or full of dramatic irony and poetic justice or twisty turning adventurism, does not matter. Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead posits them as people with a home to go back to; the content of their lore and the degree it may stimulate us does not make their pain any less real.

Thus, their inevitable deaths in the story, by hanging, are made tragic because we get to know them as people — including their inner fears and desires — perhaps better than Hamlet’s own. And that is because they are more ‘normal’ — a couple of homesick dudes who could care less about the Danish royal family’s struggles — or more akin to an “NPC”, than the king literary sadboy’s crazy life and times which have been adapted for over 400 years to myriad interpretations and angles.

For all of their competent words and existential wonderings, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are fated to die in an unknown land, still mostly unknown to themselves and us. To me, their transcendent awareness of fate — and their concerted inquiry to defeat it, even if they fail — makes them heroes of a kind, not unlike Sisyphus. ~

About the Creator

Dylan Orosz

Writer of stories.

https://thresholds-of-transformation.blog/

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.