Racist, Tyrant, Terrorist, Revolutionary.

Content and Readers in YA Fiction

‘Adult’ content is not a new phenomenon in Young Adult literature. It can be argued to have started in the last of Robert Heinlein’s juvenile novels Starship Troopers. The novel follows the archetypal coming of age format, but is largely a philosophical novel that explores the concept of citizenship and what it means to be a citizen. A backdrop of social issues is increasingly prevalent in YA literature, however, the treatment of the reader is what truly varies. Some approach this backdrop frankly; in The Ask and The Answer, Patrick Ness makes the themes of genocide and terrorism explicit while posing the question, “What is the difference between a terrorist and a revolutionary?” Koushun Takami’s Battle Royale, while also being incredibly graphic, tackles rape, child sexual abuse, prostitution, social inequality, and the pitfalls of totalitarianism bluntly. In her conversation with Hiroki, Mitsuko expands upon, “I just decided to take instead of being taken” by explaining to him, with disturbing lack of affect, that her “one thing” motivating this was when, at nine years-old, she was raped by three adults. Meanwhile, The Lions of Little Rock and The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian feel introductory in comparison. While Ness and Takami address this ‘adult’ content frankly; Levine and Alexie take a more lighthearted approach with both novels ending rather happily for the protagonists.

Battle Royale is a landmark in literature. It established survival horror as a genre and graphic depictions of violence as not simply acceptable but compelling in narratives. In Chapter 62, knowing that Yuko has poisoned the dish of stew prepared for Shuya, each subsequent line becomes more intriguing. The suspense that occurs over the span of five pages, after the poisoned dish is consumed by someone else and we witness the first death then the girls turning on each other, grows as you read, teased by seeing through Yuko’s perspective.

“Yuko raised her hand to her mouth and took three dazed steps back. With this all happening so suddenly, her body had gone numb. I have to say something. I have to explain the truth. If I let this go on… something awful… something dreadfully awful is going to happen. Then Chisato moved.” (p. 500.)

One of the most unique things about Battle Royale, in contrast to its contemporary The Hunger Games, is that its contents cover more than the social issues applicable to the primary protagonists. While The Hunger Games documents at length that Katniss, her family, and all members of the Seam live in extraordinary poverty, Battle Royale goes one step further. Takami places a particular focus on child abuse. This is most notable in regards to Mitsuko Souma. Over the course of the novel, it is slowly revealed just how badly—and horrifically—that she has been abused. Mitsuko tells Hiroki that at nine years old she had been raped by three men and the reader learns later that her mother didn’t just knowingly let them: she had set it up. We find that this was followed by Mitsuko confiding in a male teacher that she trusted—who took advantage of her, too. It’s known from the beginning that she lives with extended family and later revealed that the reason why is that when Mitsuko’s mother tried to take her out to be raped another time, Mitsuko refused to let it happen and fought back, ending in her mother’s accidental death. Takami makes it clear, however, that while Mitsuko was now free from her mother and being sex trafficked—the psychological damage had already been done. Now seeing pedophilia as something normal, outside of school, she participates in prostitution and it is stated that she has either pressured or bullied the two girls closest to her into doing it as well.

Hiroki makes this comment after his altercation with Mitsuko and her admission about being raped at nine years-old:

“Hiroki realized that she obviously could have made up that story to catch him by surprise. But he couldn’t believe that. Mitsuko had been telling the truth. And likely that had only been one small part of it. He had wondered how a ninth-grade girl, the same age as he was, could be so cold-blooded. But that wasn’t really it, was it? At her age, she’d already acquired the psyche of an adult—a disturbed adult. Or was it that of a disturbed child?” (pg. 428-429.)

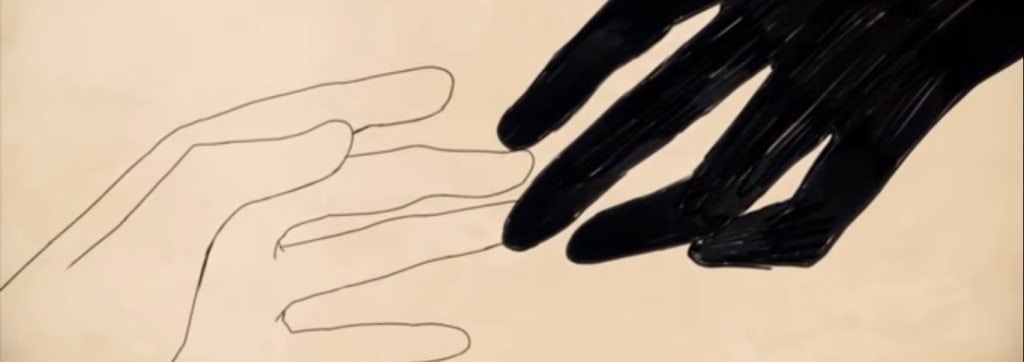

Each novel of Patrick Ness’ Chaos Walking trilogy is significant in the regards of approaching ‘adult’ content frankly. The Knife of Never Letting Go addresses the innocence of a child, what makes a boy become a man, and murder. The final novel, Monsters of Men, details the horrors of war and expands upon a line from the first novel, “War makes monsters of men.” Most significant to this paper, however, is the second novel, The Ask and The Answer. There are themes of genocide, totalitarianism, torture, and slavery as an underlay to the overarching question that Ness presents to his readers, “What is the difference between a terrorist and a revolutionary?” The way that Ness explores this question is rather unique. The narrative is presented in two different perspectives, Todd viewing events with Mayor Prentiss and Viola with Mistress Coyle. The title of the novel corresponds with the two perspectives. Mayor Prentiss establishes ‘the Ask’ as a response to Mistress Coyle, self-proclaimed revolutionary, and her movement ‘the Answer’.

Per Mistress Coyle, Mayor Prentiss is a tyrant while she and the Answer are revolutionaries. Ness blurs the lines between the two with the alternating perspectives of Todd and Viola. Contrary to the typical fashion of describing revolutionaries throughout history as being in the ‘right’, Ness presents Mistress Coyle as being just as—if not more—ruthless as the tyrant that she is fighting. Viola goes so far as to ask Mistress Coyle whether or not the latter will need to be overthrown next in this exchange:

"You want to see the world as simple good and evil, my girl,” she says. “The world doesn’t work that way. Never has, never will, and don’t forget.” She gives me a smile that could curdle milk. “You’re fighting the war with me.”

I lean in close to her face. “He needs to be overthrown, so I’m helping you do it. But when it’s done?” I’m so close I can feel her breath. “Are we going to have to overthrow you next?” (pg. 352-53.)

It is Mayor Prentiss, himself, that draws the connection between the two of them. He states to Viola that a good general will do whatever is necessary to win a war regardless of whether or not their previous occupation was in medicine and they had taken an oath to do no harm. While Viola initially doesn’t believe him, Mistress Coyle both proves his point and shows just how ruthless she can be, in willingly accepting the possibility that by placing a pressure sensitive bomb inside her bag Viola will be killed in the process, because Mayor Prentiss might be the one who either finds it or is standing nearby.

‘ … [T]he heat from the explosion singes our clothes and our hair and rubble comes tumbling down and we force ourselves under a table but something hits Todd hard in the back of the head and a long beam falls across my ankles and I feel both of them break and all I can think as I yell out at the impossible pain is she betrayed me she betrayed me she betrayed me and it wasn’t a mission to save Todd it was a mission to kill him, and the Mayor, too, if she was lucky-’ (pg. 403.)

It’s made clear after Todd and Davy, Mayor Prentiss’ son, finish construction on the building they have been making with the Spackle, that its intended purpose is to torture supposed members or affiliates of the Answer. While never directly participating, both Todd and Davy are made to watch on multiple occasions. The most significant death within the novel is that of the Healer, Corrinne. While not stated outright, it is heavily implied that Corrinne’s death is largely due in part to Mistress Coyle’s escalation of the war being waged between herself and Mayor Prentiss. In his exploration throughout the novel, Ness makes clear that the only difference between Mistress Coyle and Mayor Prentiss is their ideals and reasons for fighting. Ness shows his readers that the two leaders are opposite sides of the same coin—they are functionally the same despite their different ideals.

In this spectrum of introductory to incredibly frank, All American Boys lies more closely to that of Takami and Ness. While it is not graphic like Battle Royale or incredibly explicit in portrayal of its themes like The Ask and The Answer; it retains the frankness of both novels in how the readers are shown the social issues being addressed. All American Boys follows the same narrative style used by Ness in which both perspectives of an issue—in this case an African American boy and white boy—are seen. This style is particularly important in regards to an issue that is current and remains on-going. The only format that could have been more powerful in forcing the white reader to see how much police brutality affects not just the person, but also the family, would be second-person.

The beauty of All American Boys, like Battle Royale and The Ask and The Answer, is that it presents the issues being talked about frankly and explicitly. The narrators are shown to be directly affected by the issues presented in all three novels. Rashad is victim and survivor to police brutality, Mitsuko spent her life under the impression that pedophilia was normal, Mistress Coyle willingly put Viola at risk in her attempt to kill Todd. These three novels are all incredibly powerful. Their power comes directly from how frank that the authors are with their readers.

Rashad shows just how pervasive being wary of law enforcement is from the very beginning of the novel.

“In my bag? Man, ain’t nobody stealing nothing,” I explained, getting back to my feet. My hands were already up, a reflex from seeing a cop coming toward me. (pg. 21.)

Like its companions, All American Boys has its own uniqueness in the way it handles the social issues at hand. It would have been easier, expected by readers even, for the authors to have followed suit with news coverage and popular belief that police brutality is exclusive to white police officers and unfathomable that a black police officer would do something similar. And yet: he presents the world as it is—both white and black police officers are capable of, and unfortunately do, brutalize the very people they’ve sworn to protect. Rashad’s father confesses,

“… My partner and I jumped out of the car and approached them, and before we could even give them a chance to stop fighting, I ran over and jacked the black boy up because I knew he was in the wrong. I just knew it. […] And he fought me back, telling me I had it wrong. He slipped right from my grip and ran for the backpack. I pulled my gun. Told him to leave it. He kept yelling, ‘I didn’t do anything! I didn’t do anything! He’s the criminal!’ But now he’s wheezing, like he was having a hard time speaking. Then he grabbed the backpack. By now, my partner’s got the white kid. I tell the black dude to leave the bag and put his hands up. But he doesn’t, and instead opens it. Puts his hands inside. And before he could pull it out, I pulled the trigger.” (pg. 232-33.)

Rashad’s father continues to explain that the boy he shot had been reaching for an inhaler, the adrenaline of the situation bringing on an asthma attack, and, just like he had been told, the white boy was the criminal. The conversation ends with Rashad’s father explaining that he had come to the realization that he was “walking into situations expecting to find a certain kind of criminal” (pg. 235) and it was after this that he decided to leave law enforcement.

These issues of police brutality, racism, rape, pedophilia, torture, war, and revolutionary versus terrorist are all considered ‘adult’ or ‘mature’ content and yet their presence in these novels is incredibly important for young readers. Heinlein’s novel Starship Troopers, a juvenile novel, remains powerful and controversial to this day, sixty-one years later, because of its ‘mature’ content. Young Adult literature is at its finest and most powerful when we, as authors, treat our readers with respect and realize that they are more than capable of understanding these issues when we present them as they are with utmost frankness and explicitly.

There is no need to ‘water down’ or ‘predigest’ societal issues for our young readers. Starship Troopers, Battle Royale, The Ask and The Answer, All American Boys are each incredibly powerful and such compelling books because of their frankness and how explicit they make their subject matter to readers.

This quadrilogy of novels show the finest, most powerful, and stunning nature that Young Adult literature can have. YA literature can be an incredible and wonderful medium in which young readers can learn about the world around them, but if, and only if, we treat them with respect and provide them with explicit, frank, compelling novels that present this world truthfully.

It is of my highest recommendation that you, regardless of age, read Robert Heinlein's Starship Troopers, Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely's All American Boys, and--if you have the patience for a 600 page novel--Koushun Takami's Battle Royale.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.