Queer Authors in British Literature

A brief introduction to the Greats

Virginia Woolf lived from 1882 to 1941, and was from a large family; she had three full-siblings and four half-siblings. When she was an adolescent, she studied Greek, German, and Latin, taking books from her father’s study to read and learn from because she was not allowed to attend Cambridge like her brothers did. She had a nervous breakdown as a teenager, contributing factors of which were that at age six, two of her half-brothers sexually abused her, at age thirteen her mother died abruptly, and at age fifteen her half-sister died; these were also factors in her lifelong struggle with depression. When Woolf was twenty-two years old, her father passed away as well, and this most threatened her mental health and she was temporarily institutionalized. She would spend periods of time at Burley House, a nursing home for women with a nervous disorder, in 1910, 1912, and 1913 (Pearce, 7). What social life Woolf cared to maintain was often disrupted by her difficulties, but by and large her literary prolificness remained unimpeded.

While not one to be overly involved in the social scene of London, Woolf did take an active interest and involvement in the queer culture of the time. This ties into her close connections with the Bloomsbury Group. The Group’s philosophical and ethical ideals focused on distinguishing intrinsic worth from instrumental value, something they applied to their lives as well as to their art, allowing them to rebel against the conventions of Victorian life that restricted things such as love and writing. E.M. Forster, who was a member of the Group and a good friend of Woolf’s, was highly encouraging of “the decay of smartness and fashion as factors, and the growth of the idea of enjoyment (Forster, 111).” Indeed, a central tenet of the Group was that “They tried to get the maximum of pleasure out of their personal relations. If this meant triangles or more complicated geometric figures, well then, one accepted that too (Snow, 84).” This is in keeping with many of the beliefs of Woolf’s longtime friend and paramour, Vita Sackville-West, who was an intermittent member of the Group. Additionally, the Bloomsbury Group championed women’s suffrage, in large part due to Woolf’s influence, and Sackville-West’s by proxy.

Perhaps the single most controversial work that Woolf published was her novel Orlando: A Biography, which is extraordinary for a number of reasons— beyond the simple fact that it was Woolf who wrote it. It follows the hero/heroine Orlando across periods of history that span several centuries, during which Orlando the boy becomes Orlando the man becomes Orlando the woman. It addresses topics that were not commonly discussed in the 1920s, such as gender-changing and bisexuality. Woolf felt that, “It is fatal to be a man or woman pure and simple; one must be a woman manly, or a man womanly.” Through this lens, Woolf commented upon gender roles in society, the capabilities of women, the mind of a writer, what it is to fall in love and have your heart broken and then many years later fall in love again, with someone unexpected who does not fit the cookie-cutter form in which you were told your mate would arrive.

Orlando is special, too, for Woolf’s clever weaving of technicalities and wording to avoid the legal issues of what could potentially have her book be censored for “obscenity” or some such nonsense based on the same-sex romantic love brought up in the novel. An example of this would be this passage: “As all of Orlando’s loves had been women, now, through the culpable laggardry of the human form to adapt itself to convention, though she herself was a woman, it was still a woman she loved; and if the consciousness of being the same sex had any effect at all, it was to quicken and deepen those feelings which she had had as a man.” Woolf’s quick wit and dry observations of society also shine in this novel, such as with: “As long as she thinks of a man, no one objects to a woman thinking.” The entirety of the novel is filled with such gems of sentences and paragraphs, full passages and pages that show incredible insight Woolf’s personal thoughts and philosophies, particularly if, as she herself wrote in this very novel, “Every secret of a writer’s soul, every experience of his life, every quality of his mind is written large in his works.”

Equally meritorious of accolades is that it was written based on Woolf’s perception of and love for her Vita, for Sackville-West, a lady who is from an old and respectable English and is the wife of an international diplomat. It was of general public knowledge that she was the subject of Woolf’s latest novel, as the dedication to her was written on the inside cover page, declaring that it was for “V. Sackville-West.” In their personal letters, Vita wrote Virginia what her husband Harold had thought of it, which was, essentially, that it was brilliantly written and an astoundingly true portrayal of Vita (DeSalvo). According to her younger son, Nigel Nicholson, Orlando was “The longest and most charming love letter in history, in which Virginia explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her.”

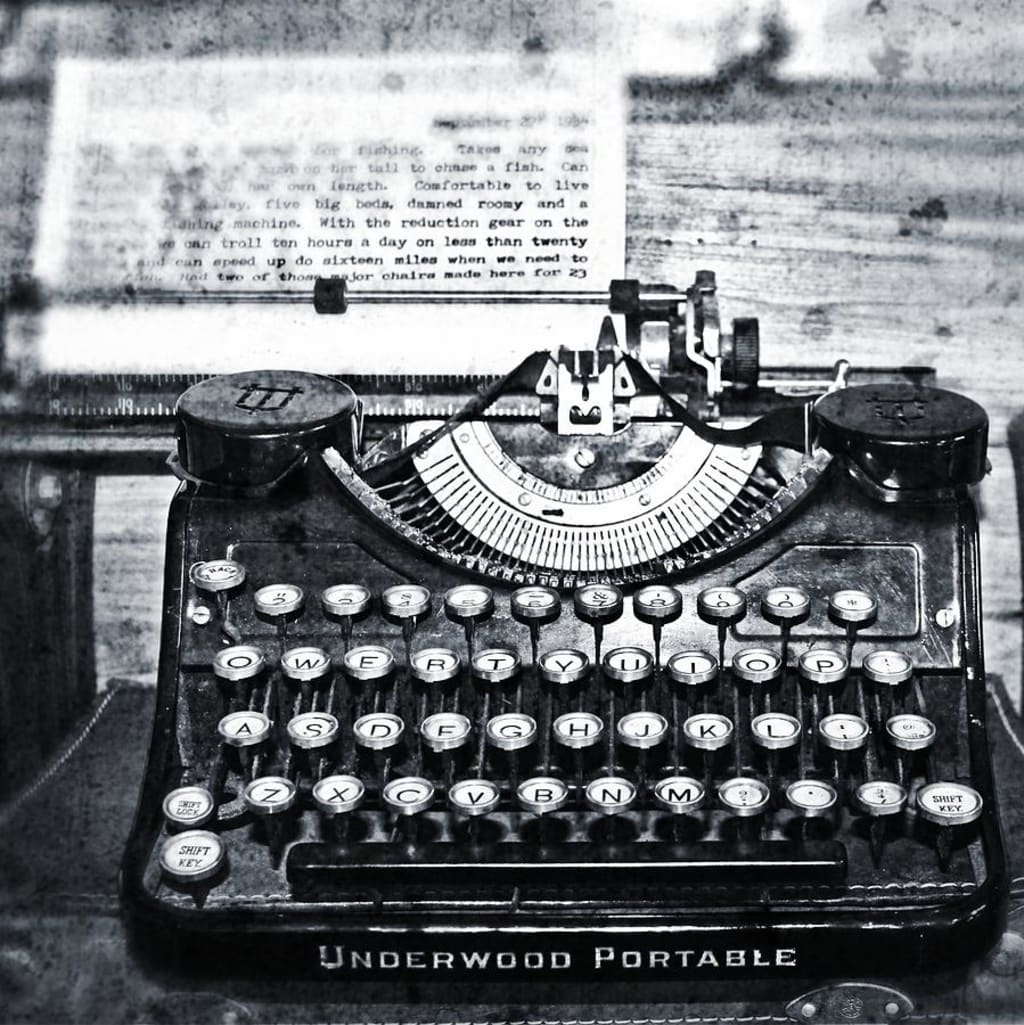

In 1928, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, a book centering around a lesbian main character, was challenged. Less than a month before Virginia herself would release Orlando, The Well of Loneliness was brought to court on trial for obscenity. Virginia testified on behalf of Hall, and signed a petition on the fatal effects of censorship upon writers. As she herself would write in A Room of One’s Own, which would be published a years later, “To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries.”

Another of Woolf’s queer-related literary contributions is Mrs. Dalloway, which is incidentally her best-known work today. In addition to thoughtful exploration of the effects of World War One, the issues of mental health, and paths not taken in life, Mrs. Dalloway contains a romantic subplot between two women. The title character, Clarissa Dalloway, remembers being young and ecstatically in love with a girl in her circle of friends, Sally Seton, when she was a young woman. She recalls these memories with treasured adoration and a lingering protectiveness— both of Sally, and of the love they shared, which she felt to be the most genuine and pure love she experienced in her life.

In terms of long-term impact, Woolf is not one who would have foreseen herself the subject of units of study nearly a century later, who could have imagined that her novels would be a part of core curriculum literature across America. She wrote for the sake of writing, for the integrity of the work and for her own peace of mind. In her own words, “So long as you write what you wish to write, that is all that matters; and whether it matters for ages or for only hours, nobody can say (Woolf).” And yet, Virginia Woolf is still included in the list of fundamental British authors, considered integral to literary and lesbian culture alike, rarely mentioned without an allusion to her beloved Vita.

Vita Sackville-West lived from 1892 to 1962, officially titled the Honorary Victoria Mary Sackville-West (or Lady Nicolson once she married) and was a poet, a novelist, and a gardener. She was the only person to win the Hawthornden Award for poetry twice — first in 1927 and again in 1933 —, was made a Companion of Honour for her services to literature in 1947, and created the incredible gardens at Sissinghurst Castle, her home later in life where she would one day die at age seventy.

Sackville-West was the only child of a baron and his wife Victoria, for whom she was named. Her relationship with her mother was an incredibly complex one. Victoria was self-centered, ruthless, and very beautiful; she had dramatic affairs with a number of men, and needed constant validation via endless adoration, something she often sought from her only daughter, a child who tried desperately but was never up to the task. Victoria had great and intense mood swings and bouts of emotional outbursts, something Sackville-West grew up on the receiving end and in the shadow of and indeed endured long into her adulthood. From her mother, Sackville-West became convinced that “the world was a hard place where one must fight one’s own battles for one’s own best advantage,” a feeling she confessed to in a letter to Woolf (DeSalvo).

To survive a childhood ruled by the tumultuous emotions of a mother who was too much of a mess herself to provide any kind of consistency, love, or sense of stability, Sackville-West retreated into the realm of the history that pervaded the family estate of Knole; it became her sanctuary on an intimately personal level. This is one of the reasons it caused her so much helpless frustration and a deep sense of personal loss when, upon her father’s death, Knole passed to her male cousin instead of her (Bell). This occurred during the year in which Woolf was writing Orlando, and so, in a gesture of incredible love and understanding, she created Knole within the pages of her novel and bestowed it upon the character Orlando, Sackville-West’s fictional counterpart.

In 1913, Sackville-West married diplomat Harold Nicolson. Both were bisexual, and they each had same-sex affairs before and after they were married (Glendinning, 411). Notable of Vita’s side was Rosamund Grosvenor (with whom she had already been involved when she became engaged to Nicolson), Violet Trefusis, and the polyamorous relationship of Evelyn Irons and her lover Olive Ridner, whom remained a close friend of Sackville-West’s. It was her view that, “Some were born to be lovers, others to be husbands, [Nicolson] belongs in the latter category.” It made sense to her that love not be confined to a legal document, as she also wrote, “I cannot abide the Mr. and Mrs. Noah attitude toward marriage; the animals went in two by two, forever stuck together with glue.”

Sackville-West was a highly intelligent and fiercely opinionated woman, and had a wide defiant streak that made itself known not only in how she chose to live her life but also appeared in much of her writing. The novel for which she is most well-known is All Passion Spent, which centers around the idea the control women have over their own lives and society’s constrictions. It was published in 1931 by the Woolf’s Hogarth Press, and the cover art of the novel was actually done by Virginia Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell. For years Virginia ran the Press with her husband, Leonard Woolf, and together they published many of Vita’s writings through the Hogarth Press.

To epitomize Sackville-West’s fundamental beliefs in two quotations, one must look toward what she has written on the accepted authority, and the disparity of genders. “Authority has every reason to fear the skeptic, for authority can rarely survive in the face of doubt.” Quintessentially Sackville-West, both in eloquence and bold cleverness, as is “Women, like men, ought to have their youth so glutted with freedom they hate the very idea of freedom.” In consideration of this, it is unsurprising that she and Woolf were so intimately and intrinsically significant in one another’s life.

Woolf and Sackville-West met for the first time on December 14, 1922. Woolf was forty, had endured three major terms of insanity, had published three books and was already considered a notable force in the literary world. Sackville-West was thirty, was established as a fairly successful author, and had published several volumes of poetry and fictional works. Both women had been married to their respective husbands for nearly a decade, and both made such an impact on the other that each wrote of the meeting in either their diary or in a letter to a loved one.

Four days after meeting Woolf for the first time, Sackville-West wrote in a letter to Mr. Nicolson, “I simply adore Virginia Woolf, and so would you. You would fall quite flat before her charm and personality…Mrs. Woolf is so simple: she does not give the impression of something big. She is utterly unaffected…At first you think she is plain, then a sort of spiritual beauty imposes itself on you, and you find a fascination in watching her…She is both detached and human, silent till she wants to say something, and then says it supremely well. She is quite old. I’ve rarely taken such a fancy to anyone, and I think she likes me. At least she’s asked me to Richmond where she lives. Darling, I have quite lost my heart (DeSalvo).” This sliver of contemplation and affection was remarkably prescient of the twenty years to come in which the two women would share in literary discussions, love letters, sincere admiration, and protective love.

In Woolf’s diary on meeting: “the lovely aristocratic Sackville-West last night at Clive’s. Not much to my severer taste…with all the supple ease of the aristocracy, but not the wit of the artist. She writes 15 pages a day—has finished another book—publishes with the Heinemanns—knows everyone—But could I ever know her?” And after sharing meals and each other’s books, Woolf contemplated her shifting feelings once again in her diary, writing, “She is a pronounced Sapphist, & may…have an eye on me, old though I am. Nature might have sharpened her faculties. Snob as I am, I trace her passions back 500 years, & they become romantic to me, like fine yellow wine.” In Sackville-West, Woolf would come to see the paragon of women, running a household and striding through grocery stores with pearls draped around her neck.

Sackville-West would grow to be quite close to the Woolfs, and became enfolded in their intellectual and personal lives of fairly selective company. The dogs both women had over the years would become fond of their Human’s closest friend, Sackville-West would be incredibly strict and endearingly sweet when Woolf was unwell, and Woolf listened to everything Sackville-West had to say and ultimately accepted every facet of her complex and flawed life. Mr. Nicolson was a diplomat, and would travel for extended periods of time; sometimes this meant Sackville-West was left home alone with their boys and their dogs and would be kept affectionate company by Woolf, and sometimes this meant Sackville-West would be away for months at a time, sailing off the Indian coast, trekking through Persia, going to social events in Berlin, and would write extensive love letters to “Dear Mrs. Woolf” at home in London.

A wondrous example of the letters between these two great minds of literature is from when Sackville-West was away in Teheran for months at a time, only four years after their initial meeting. It exemplifies the more subtle nuances of their relationship and the immense care that existed between them.

V.S.W., Thursday, January 21st, 1926: “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your un-dumb letters, would never write so elementary a phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a title gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it would lose a little of its reality. Whereas with me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal. So this is really just a squeal of pain. It is incredible how essential to me you have become. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any the more by giving myself away like this—But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defenses. And I don’t really resent it.”

V.W., Tuesday, January 26th, 1926: “Your letter from Trieste came this morning—But why do you think I don’t feel, or that I make phrases? ‘Lovely phrases’ you say which rob things of reality. Just the opposite. Always, always, always I try to say what I feel…”

V.W., Sunday, January 31st, 1926: “…Yes, I miss you, I miss you. I dare not expatiate, because you will say I am not stark, and cannot feel the things dumb people feel. You know that is rather rotten rot, my dear Vita. After all, what is a lovely phrase? One that has mopped up as much Truth as it can hold.”

In their literary works as well as their personal letters, both Sackville-West and Woolf contributed a great many more lovely phrases to the world than there had previously been, leaving indelible marks on the realms of literature of reality. Though they are among the greatest British authors of the twentieth century, the somewhat smaller field of queer British novelists of the same time period would be incredibly incomplete without the male perspective, which Christopher Isherwood provides like none other.

Christopher Isherwood was a gay English novelist who lived from 1904 to 1986, and spent much of his life living abroad— especially in Germany, exploring language, and sexuality, and the culture of Berlin (Isherwood). He wrote several stories set in Germany, Mr. Norris Changes Trains and Goodbye to Berlin, out of which eventually came the famous musical Cabaret. For this reason alone Isherwood would most likely be considered an icon of queer culture, but later in life he had a public relationship — in an era in Hollywood in which this was not generally acceptable — with longtime partner Don Bachardy that lasted until Isherwood’s death. Of particular note is the fact that in 1976 at age seventy-two Isherwood published a courageously honest memoir in which he came out by deliberately not censoring himself the way he had so carefully done in all the writing he’d done when he was younger.

While in Germany, Isherwood befriended Magnus Hirschfeld, who founded die Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, or the Institute for Sexual Science, in Berlin along with the renowned psychotherapist Arthur Kronfeld. It was a non-profit foundation that was an early research institute on the matter of gender and sexuality, and included an entirely unique library put together by Hirschfeld on same-sex love and eroticism, which later would fall victim to the Nazi book burning (Oosterhuis). The Institute was more than a library, however; it also had divisions for medical, psychological, and ethnological purposes, and an office that specialized in marriage and sex counseling. It employed transgender people, worked with the Berlin police department to decrease arrests made of cross-dressers on suspicion of prostitution, encouraged sexual education and contraception and the treatment of sexually transmitted illnesses, rallied for women’s emancipation, and was a worldwide leader of civil rights and the understanding and acceptance of queer and transgender people (The Times).

At the time that Isherwood was living in Berlin, there was a law in effect in Germany known as Paragraph 175 or Section 175 that criminalized same-sex acts between men, from May 15th, 1871 to March 10th, 1994. During this time period, that law was used to convict over 140,000 men. Unsurprisingly, it was a law that in the 1930s the Nazi Party would pursue and abuse, broadening it and using it to persecute homosexuals, leading to thousands of gay people of all races dying in concentration camps during the Holocaust (Tipton, 584). This section of the German criminal code is something Isherwood was acutely aware of, and was as involved in fighting as he dared to be. As he would go on to write, “What irritates me is the bland way people go around saying, ‘Oh, our attitude has changed. We don’t dislike these people anymore.’ But by the strangest coincidence, they haven’t taken away the injustice; the laws are still on the books.”

In fact, a significant amount of Isherwood’s writing and lectures pertained to injustice, intolerance, and the global plague of demonizing what is unfamiliar. A particularly interesting and colorful way of phrasing his thoughts on this is the following: “Do you think it makes people nasty to be loved? You know it doesn’t! Then why should it make them nice to be loathed? While you’re being persecuted, you hate what’s happening to you, you hate the people who are making it happen; you're in a world of hate. Why, you wouldn’t recognize love if you met it! You'd suspect love! You’d think there was something behind it — some motive — some trick (Isherwood, A Single Man).” The style of Isherwood’s wording here makes this sentiment one that is more easily accessible to a broader number of people, rather than alienating the reader by giving them the impression of an emotion with which they would be unable to empathize. He had an intimate understanding of how that which is different can be a threat to established societal norms, for as he wrote in the same novel, “A minority is only thought of as a minority when it constitutes some kind of threat to the majority, real or imaginary. And no threat is ever quite imaginary.”

It was Isherwood’s belief that “by helping yourself, you are helping humankind. And by helping humankind, you are helping yourself. That’s the law of all spiritual progress.” In this spirit, especially as he grew older, Isherwood became more open about his sexuality and shared more of what he had learned over the course of his life about travel and life and writing. He became one of the leading artistic paragons of queer culture, particularly for gay men. “Their life with one another and with their countless friends became a kind of shared artistic project, and their relationship was to become a model for many gay men undertaking long term partnerships in the new openness of liberation. Its iconic status was enhanced by the double portrait of them which David Hockney painted in 1968 (The Christopher Isherwood Foundation).”

Three of Isherwood’s novels (The Memorial, Mr. Norris Changes Trains, and Lions and Shadows) were published by the Woolf’s Hogarth Press. This happened primarily while he was traveling back and forth between London and Berlin fairly frequently; he met Leonard Woolf several times, and the singular time he met Virginia — whom he had long since admired tremendously for her literary talent — left an incredible impression on him. He wrote about the awe he felt at being in her presence in Christopher and His Kind, and again in The Paris Review which was included in the anthology of literary criticism The Art of Fiction. In the latter recalling of that meeting, Isherwood wrote,

“She was one of the most beautiful women I’ve met in my life, really absolutely stunning, in a very strange way. Of course she was middle-aged when I knew her. She had the quality that manic-depressive people have of being up to the sky one minute, down into despair and darkness the next. She had these terrible phases, as we know now; but what one saw was her tremendous animation and fun, on a gossipy level. She loved tea-table talk. One time I was at her place with a lot of people, and something happened to me that’s never again happened in my life. We had tea, and she said, “Do stay to dinner.” So I did and sat there absolutely enthralled. And suddenly, with a terrible shock, at about ten in the evening, I remembered that I was supposed to be going on a very romantic trip to Paris with somebody who was in fact waiting at the airport at that moment. I had completely forgotten about it. She had that effect on people.”

Virginia Woolf. Vita Sackville-West. Christopher Isherwood. Three members of the long line of queer historical figures who have achieved remarkable things, each exemplary in the field they all share— that of writing, of finding the words to create new life between the pages of printed paper. Their phrases, as well as all that they stood for, every single belief that they held and stance that they took, have long outlasted their lifespans. In one form or another, they will appear in the lives of many queer people today, whether it is discovering Virginia Woolf in English class, becoming intrigued with the real-life inspiration Vita Sackville-West for the character Orlando, or falling into the mind of Christopher Isherwood from whence Cabaret sprang. There have been many novels since 1928 that have been penned in the style of Mrs. Dalloway, an impressive amount of today’s feminist philosophies can be found in All Passion Spent, and the I Am a Camera concept of Isherwood’s (“I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.”) has been thoroughly explored by many kinds of artists. The impact and influence these three individuals have had, and continue to have, is vast, varied, and indisputable.

Work Cited

Bell, Matthew. Inheritance: The Story of Knole and the Sackvilles by Robert Sackville-West. “The Independent,” May 16, 2010.

DeSalvo, Louise and Mitchell A. Leaska. The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf. Quill, 1985.

Forster, E.M. Two Cheers For Democracy. Penguin, 1965.

Glendinning, Victoria. VITA. A Biography of Vita Sackville-West. Knopf, 1983.

Isherwood, Christopher. A Single Man. Simon & Schuster, 1964.

Isherwood, Christopher. Christopher and His Kind. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1976.

Oosterhuis, Harry. Homosexuality and Male Bonding in Pre-Nazi Germany: The Youth

Movement, the Gay Movement, and Male Bonding Before Hitler's Rise: Original

Transcripts from Der Eigene, the First Gay Journal in the World. 1991.

Pearce, Brian Louis. Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group in Twickenham. 2007.

Snow, C.P. Last Things. Penguin, 1974.

The Christopher Isherwood Foundation.

The Times, “League for Sexual Reform International Congress.” September 9, 1929.

Tipton, Frank B. A History of Modern Germany Since 1815. University of California Press,

2003.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Hogarth Press, 1929.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.