Ikiru Movie Review

Reviewing Ikiru 65 Years after its making

In Japanese, Ikiru means “to live” and by viewing the widely unmentioned masterpiece of Akira Kurosawa, one might seek compassion rather than anger, another might find love instead of hate, or meaning instead of a vacant existence. In Ikiru, Takashi Shimura portrays Kanji Watanabe vulnerably and powerfully. At the beginning of the film, Watanabe is diagnosed with stomach cancer. His life flashes quite literally before his and the audience’s eyes. From the opening scene of the stark monochrome X-ray chest of Watanabe, the grimace face of death follows his sauntering like a shadow; Watanabe has a frown glued to his chin. Ikiru means “to live,” as that is the quest that the director, Kurosawa, desired to observe.

Akira Kurosawa manages to encapsulate “genius” with his lesser known filmography like Ikiru. With his most notable film Seven Samurai, Kurosawa crafted drama through action and composed scenes that elevated the story and characters. With the drama, Ikiru, Kurosawa crafted empathy through movement and framed the character of Watanabe to appear like a pathetic old man, living a normal and mundane life. Seemingly, it is socially and artistically trite to craft a meaningful plot around the eventual death of a character. It is seen in every form of filmmaking, literature, or portrait. From comedies like The Bucket List and Harold and Maude to dramas like The Seventh Seal and The Hours, the question of life and death is a primary theme amongst notable films. But the question of life and death is swirling the drain of culture and art. It is sucking the life from the audience with the intention to either manipulate desolation and despair or cause pensiveness. Kurosawa chose to craft a widely covered topic with thoughtfulness. From the premise alone, there are trite questions being begged and verifiable emotions being evoked. But Kurosawa manages to elevate a more important question than “what would you do if you had a few months to live?” Instead, he asks about the meaning of life, and by extension, he evaluates the human condition within the framed images.

The two-part structure of Ikiru strengthens the climax of the story. In the first part, Watanabe's perspective provides insight into the character, his intentions, the initial themes, and eventually his demise. In the second part, the interrogation of memories regarding his last few days on earth, it provides context to the simple but seminal question: What is the meaning of life? In the demolition of Kanji Watanabe’s spirit, he wanders mercilessly, attempting to validate his success in work and equal the scales of his life with meaning.

Intentional by Kurosawa’s direction, the film begins at a slow pace so that the incumbent memory of Watanabe’s wounded cries leaves an imprint on the audience. After finding out about his death, he goes on a binge. He's desperate to validate his feelings and unfold the memories of his life with alcohol and some company. He tells a stranger that directs him towards the red-light district, where gambling and drinking also take place, that he can't die. “I just can’t die — I don’t know what I’ve been living for all these years.” While Watanabe’s tears snake through the wrinkles on his face, he informs a stranger that he is merely looking for a good time. By the end of the night, Watanabe drunkenly sings, “Life is Short, Fall in Love Dear Maiden” with that mysterious man. From the beginning of the film to his drunken attempt at singing, it is made clear that Watanabe holds little value in life. Having never accomplished anything and working in the same occupation for 30 years, the slurred lyrical rendition of, “Life is Short, Fall in Love Dear Maiden” weighs heavier than expected.

Watanabe desires meaning and peaceful catharsis. He is desperate to leave happier than how he lived on earth. But he wonders how to accomplish this. In his absence from work, while he's in the red-light district and wondering his city, a young woman from work searches for his stamp to approve her resignation. Upon finding him, desolate and protesting death with saki, he asks that she spend the day with him. Her presence motivates him to speak with his emotionally distant son, but their interaction only deepens his despair. Encumbered by the thought of being pathetic and meaningless in life to not only himself but also to his child and by listening to the young woman who decided to spend the day with him, Watanabe decides to accomplish one thing before he passes. And he does so with the help of a few misfits. Watanabe begins constructing a park for a neighborhood known for being littered with poverty. His determination to construct the park annoys and surprises his co-workers. But before the audience can discover whether he actually made the park or not, the scene cuts to part-two.

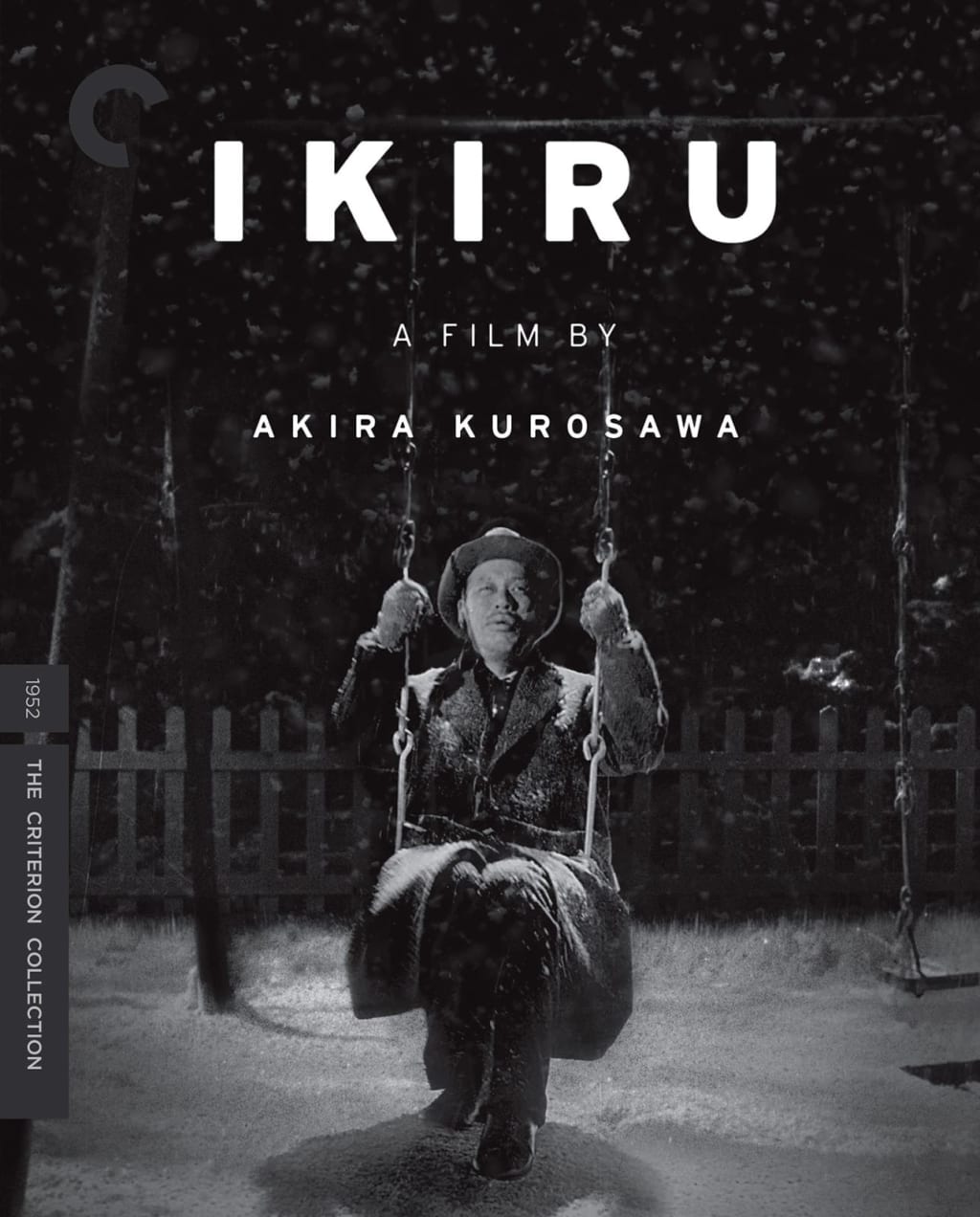

The second part of the two-part structured film follows the angry, confused, inspired, and apathetic mouths of Watanabe’s family, friends, and co-workers. It begins with his funeral and manifests into a retrospective of his last few days on earth. During his funeral, a discussion circulated about his last days where he was perceived as a desperate old man, attempting to build a children’s park. Throughout the two and a half hour film, Kurosawa attempts to convince the audience that Kanji Watanabe is not special. He is not an extrodenary man that you would find on a silver screen but instead, he's presented as pathetic and senile. You can see that with every word he utters to his co-workers and children. As the family reminices on his last effort, his family guesses that he knew about his eventual death. Then they discover that his last words were from a sweet song he sang while sitting on a swing in the park he built. His life, while seemingly mundane, emotionally moved others. But this was only in retrospect. Watanabe is perceived as desperate while his family and friends talk about him during his funeral. But the song he sang suggests something else.

By the conclusion of the 1952 drama, the audience discovers that everyone is Kanji Watanabe; lost souls that are desperate for meaning. Watanabe occupies his last days on earth by attempting to build a park for children. His desperation is as tangible as his fear of time and death. But Watanabe successfully builds a park and finds himself swinging and smiling until his last breath. While he is hunched over on that swing in a park that he desperately constructed in the last few months of his seemingly meaningless life, a blanket of snow washes over Watanabe. He sings, “Life is Short, Fall in Love Dear Maiden.” In the last breath that flowed through his lips and the final pulse that thumped in his chest, Watanabe discovered the meaning of life. The song only solidifies that, as he had finally fell in love with something: his meaningful life. While snow gathered at his feet like a mountain of sugar and winter winds blew past his no-longer frowning face, he stopped fearing death and embraced his little park. He discovered that the meaning of life is not a fossil in the ground; it cannot be dusted until discovery. Instead, the meaning of life became an observation and only confirmed through the respective perspective of the participant: himself.

In Ikiru, there isn't a defined meaning of life, but Kanji Watanabe discovers his purpose with the park. Akira Kurosawa’s observation on life and death solidifies that undertaking any task becomes the meaning of that man or woman's life. So whether it be a construction worker, lawyer, father, daughter, or artist, humans create their own meaning. Life doesn't craft it for you. Instead, you do it yourself. The transcendentalist nature of the film encourages a modern audience to view it without the lens of cynicism. While an observation on the human condition, Ikiru remains a cinematic expression of existentialism. Since film is a materialization of thought, movies like Ikiru beg questions without actually formulating a sentence. Acclaimed auteur, Robert Bresson once said that, “You can’t show everything. If you do, it’s not longer art. Art lies in suggestion.” With Ikiru, the meaning of life is the biggest question mark on the page but how he tells the story to insinuate meaning, character, plot, and Watanabe’s demise remains only in Kurosawa’s distinct understanding of the language of cinema. The interpretation of his film remains up for debate. But rest assured, everyone has a purpose. Just listen to Kanji Watanabe, the man on a swing who sings about life until the last note falls from his lips like the snow that covers his frown.

__

As always, thank you for reading. Any and all tips are deeply appreciated :)

About the Creator

Bella Leon

Welcome to my digital diary!

I have a vast but useless knowledge of cinema, and I just love to write.

You can expect to find random articles regarding various subjects, poetry, short stories, and anything film related. Happy reading <3

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.