“It is as inhuman to be totally good as it is to be totally evil.” — Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Last night I had a peculiar dream.

In the dream, several men, dressed as Droogs (the criminal gang led by "Little Alex" in Stanley Kubrick's iconic 1971 cinematic adaptation of Anthony Burgess' dystopian masterpiece, A Clockwork Orange), had captured their own leader; who, I take it, was on the run for unspecified crimes against his former friends. The Droogs had this poor fellow lie flat upon the hard floor, and then stood upon him, their black, shiny military boots pressed into his flesh. The one responsible for this curiously medieval form of punishment told him, "You just wait until the rest of us get here. It might just kill you." Indeed, having hundreds of pounds pressing down upon your ribcage, like the unfortunate Giles Cory at Salem in 1692, would, indeed, bring about a cruel and merciless death.

One would be hard-pressed (no pun) to find compassion though in A Clockwork Orange, which is what I watched immediately upon awakening from the dream. (I often take my cues for what information or areas of interest I should give my attention to from dreams, pursuing those things immediately in my waking life.) Irony, sardonic satire, and cruel, vicious twists of fate perhaps; but, as for a world brimming full of "peace, love and understanding"? Most certainly not. It is a film that examines the moral quandaries of the modern age: the burden of personal choice versus state-controlled compulsion. How much punishment is enough for the wrongdoer, and what is his or her final place in a society that is as equally ethically bankrupt as the criminal that is consigned to the foulest, most fetid prison cell? Are some men born with the mien of killers and rogues? Or are these moral choices the result of maleducation, or maladaptive behavior patterns that have been inculcated in them from their childhood? And what should society do, in the face of such an assault?

The question posed by the title of the work, suggested by an old Irish saying "As queer as a clockwork orange" (i.e. as strange as making something natural, like a piece of fruit, into something unnatural, like a clockwork toy), centers around the character of Alex (Malcolm McDowell), who seems to be possessed of the innate nature to do crime, to revel in violence, and exalt theft, rape and even murder. Again, what part of this is a natural, innate, inborn aspect of his being? What part of him is informed by moral choice? To what does society owe him, as regards his psychopathy? And, is it thus "moral" to castrate or reeducate him, to put him through a conditioning that strips him of his ability to choose right from wrong; is "mind totalitarianism" the answer to cleaning up the world of savagery and crime? All troubling questions, as relevant today as they were in 1971.

We begin with Alex, a close-up of his face, pulling back to reveal his fellow Droogs at the Korova Milk Bar, a place where you can get "milk with Vellocet, milk with Synthemesc, and milk with Drencrom. This would sharpen you up and get you ready for a bit of the old ultra-violence."

His environment is a dark, seedy, otherworldly place of pornographic statuettes that dispense drugged milkshakes, weird dayglo posters and writing, and black walls. His fellow Droogs surround him, as posing for a portrait. The principle Droogs are Georgie, a cockney-and-Nadsat (i.e. the fictional language spoken by the thug gang members of Clockwork Orange world, made up of appropriated Russian words and what seems to be Elizabethan English) spewing heavy with a sort of rogue's charm, and Dim, a semi-articulate buffoon with long locks of hair, lipstick, and a hideous, moronic guffaw. The characters are played, respectively, by Warren Clarke as Dim, and James Marcus as Georgie.

The strange, heavy opening theme, a synthesized adaptation of a classical air, gives way to the next scene. The Droogs accost a wino lying under an overpass. The wino, a philosophic drunk, implores the masked menaces to "Go ahead! Do me in, ya' bastard cowards! We don't want to live anyway. Not in a stinking world like this!"

He goes on to say:

It's a stinking world because there's no law and order anymore! It's a stinking world because it lets the young get on to the old, like you done. Oh, it's no world for an old man any longer. What sort of a world is it at all? Men on the moon, and men spinning around the earth, and there's not no attention paid to earthly law and order no more.

He is then "tolchocked"; i.e. beaten savagely by the Droogs, while they laugh and run away like hyenas.

Next, they battle a Hells Angels-style biker gang in an abandoned theater, interrupting them during the course of an attempted rape. The rape victim is toyed with before being forgotten at the approach of the Droogs, and "Stinking Billy...thou cheap bottle of chip oil," spits a wad of tobacco juice, flicking his stiletto as the two rival gangs get down to business. The Droogs seem to win easily.

Just getting warmed up, they steal a car, going for a dangerous, high-speed joyride, before finding themselves at the remote hideaway of a writer, Mr. Alexander (Patrick McGhee, whose house, ironically enough, has a glowing sign outside that proclaims it "HOME"), who is, we later find, a political dissident, a writer of "subversive literature." His wife (Adrienne Cori) is young, tall, dressed in a red one-piece, and desirable.

Their home is sophisticated and upscale, with nude art on the walls (the sexualized and pornographic imagery a running theme throughout the film), and large bookcases. Alex, using the ruse of needing to use the phone "As there's been an accident, missus!", gains for himself and his fellow Droogs entry. Then, it is destruction and terror, as the masked marauders proceed to terrorize the couple, destroying their book cases, dancing on Alexander's writing desk, and kicking him to the floor.

In a horrifically comic scene, Alex proceeds to dance, light of foot, across the floorboards, bellowing the old Bing Crosby tune, "Singing in the Rain," while stopping, upon occasion, to viciously kick Mr. Alexander in the stomach. Slowly, while she is gagged and being held at bay, he uses scissors to cut away the dress of Mrs. Alexander, revealing at first her breasts, and then cutting away the rest of her outfit. He then drops his drawers. His masked visage is seen in close-up, instructing Alexander to "Vide well, little brother! Vide well!" as he rapes the man's wife.

"I Ain't Your Brother No More, and Wouldn't Want to Be!"

The trouble, at least for Alex, begins when, getting back after a long night of robbery and rape, the Droogs find themselves sitting,once more, in the Korova, drinking their drugged drinks (which, incidentally, are dispensed through the nipples of the pornographic statues by reaching between their legs). A group of "sophistos" from the television studio, none of whom look as if they belong in this particular low-rent and surreal juice bar, are celebrating at a nearby table. The woman with them, taking a sheet of music, begins to intone, in beautiful, regal German, the aria from Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" (Ninth Symphony, Fourth Movement). Dim makes a disgusting sound, and is promptly struck in the balls by Alex with his cane. Alex, of course, cannot tolerate such an odious and uncharitably rude response to lovely, lovely Ludwig Van. Thus, in a manner of speaking, his pretentions to bourgeois appreciation of the finer forms of music are, unwittingly, his own undoing.

He returns home in the wee hours of the morning. His apartment block, a "municipal block" with a number in place of a name, is occupied by his elderly parents. The foyer of the place suggests the dystopian squalor and deterioration that lurks all around. There is graffiti on the walls, covering a once beautiful, ornate mural, and there is debris and litter in the halls. The elevator is, predictably, broken. His room is an unconventional bedroom with curtains bearing Beethoven's image, plaster dancing Christs in a row, and a boa constrictor in a drawer. In another drawer, he has a hoard of stolen booty: watches, wallets, wads of cash, etc. Alex relaxes listening to a microcassette of Beethoven, dreaming himself a vampiric entity, envisioning violent scenes; explosions, hangings, rock falls in a primitive world. His mind is a psychopathic torrent of bloody and erotic, ghastly visions.

At a shopping mall, a place whose walls are black but contrasted with dayglo posters and sexualized imagery, Alex, dressed as an Eighteenth Century lord, meets up with two young women who seem to be fellating huge, rainbow-colored dildos. These are undoubtedly supposed to be candy, but the scene opens with a suggestion of oral sex. Alex invites both of them home. ("Come with uncle and hear all proper. Hear angel trumpets and devil trombones. You. Are. Invited!")

Next, we have a fast-motion menage a tois set to the "William Tell Overture" by Rossini. (The scene is comic, yet also underscoring the fast, loose and violent nature of sex and entertainment in our dystopian future.) Afterwards, Alex, clad in his underwear, has a confrontation with his probation officer, Mr. Deltoid (Aubrey Morris), who suspects Alex is again up to no good. Informing him that, next time, it "will not be the corrective school. Next time it will be the stripey hole, yes?" Alex innocently replies, "The Millicents have got nothing on me, brother. Sir, I mean!"

Coming downstairs, he meets his three Droogs (the third, "Pete," played by Michael Tarn, has no dialog and is a virtual non-entity, what actor Jack Nance once called the movie equivalent of a "door-stop"). Georgie, quite angry at what he perceives as the abuse of Dim, says, "No more picking on Dim brother. That's part of the new way!"

Alex, pretending to be pleased by this new burst of initiative on the part of his underlings, says, "Tell me more, Georgie-Boy. Tell me more!" Georgie goes on to complain that they are tired of small heists, and want a "man-sized crast." The idiotic Dim guffaws continually and agrees with him. Off they go, walking by what seems a canal. Alex attacks in a famous scene, easily besting his three comrades, throwing each into the water, his face a savage mask of terror. He slices Dim's hand as he struggles and reaches for help.

Afterward, "Snug and safe in the Duke of New York," Alex, thinking he is firmly back in control as the undisputed leader, is lead into a trap. Taken to a health resort run by "like this rich old pititsa," he walks in on a skinny older woman doing stretches in a leotard on the floor. Her opulent home is filled with the same sort of erotic art appropriated, it seems, culturally from the gang-infested street life of the Nadsat youth; expropriated and made "radically chic" for the upper class.

The exchange between them is farcical; the old woman is outraged instead of frightened by Alex, and proceeds to try and brain him with a huge glass penis and testicles. Instead, he brings a vase down upon her head after a curious little circular dance, with the camera at his back. The requisite splash of gore is replaced with a quick cut to a close-up of an illustrated tunnel of what appear to be human lips and teeth.

Alex goes outside and is busted over the cranium by Georgie, his three Droogs running away laughing, leaving him for the police. Taken to the station, beaten (after acting like a rude, belligerent vulgarian), Mr. Deltoid enters to inform him that "You are now a murderer, Little Alex. Your victim has died."

Staja 84F

Alex is convicted and sent to "Staja 84F" (the word is a portmanteau of "State Jail," and reminiscent of the German word for POW camps, Stalag), sentenced to fourteen years. Here, he becomes a model prisoner, lusted after by the other prisoners because of his youth and beauty, and secretly desired by Chief Officer Barnes, a comic martinet played expertly by actor Michael Bates.

He soon befriends the prison chaplain (referred to as the prison "Charlie." As in: "Charlie Chaplin"), a huge cartoon of a sweating, sanctimonious and wrathful preacher (Godfrey Quigley). Alex reads the Bible, envisioning himself as an Old Testament slayer, reclining on a couch and getting fed grapes by slave girls (when not whipping the back of Jesus Christ, "dressed in the height of Roman fashion") He confides to the pastor that he is wanting to take the rumored new treatment, the "Ludovico Treatment," an experimental form of behavior modification that supposedly "cures" incorrigibles of their criminal tendencies. The Chaplain, telling him that "goodness comes only from within; when a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a man" (meaning as an act of moral free will), says he will put in a word for him anyway.

At a visit from the Minister of the Interior (Anthony Sharp), Alex realizes his chance, getting the man's attention, and impressing him enough with his youth and aggressive nature that he is immediately chosen for Ludovico.

He is signed out of regular prison, then taken to a clinic where, after resting, he is told, by a Pollyanna-like nurse (Carol Drinkwater), that he is just going to be "shown some films."

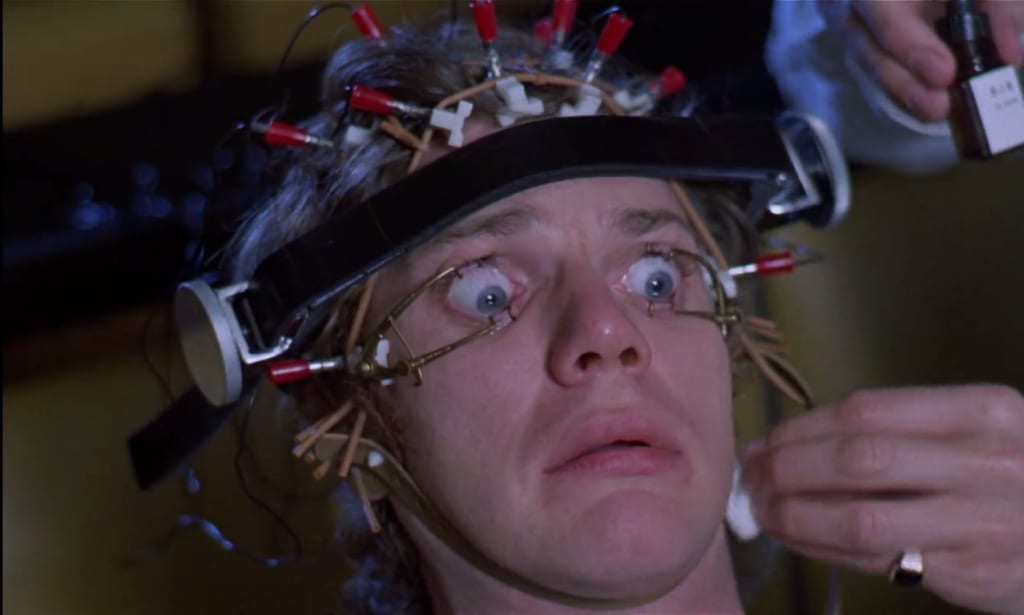

And what films these are! Belted, as if in a racing car or space capsule, into a front row of theater seats, Alex is tied up tightly in a straight jacket. Lid clamps are placed against his eyes so he cannot close them, and his head is wired with electrodes. It is a by now iconic cinematic image, as indelibly imprinted on our collective psyche as the images Alex is forced to "vide" in the "cine."

The images depict actors, dressed in the white outfits preferred by Droogs, beating a man senseless. Then, the scene shifts to depict them raping a woman with an intense wig of red hair.

While all of this is occurring on screen, a serum, created to simulate intense feelings of horror and sickness, if not of living death, is injected into him, causing him a horrible physiological response. He of course associates these, subconsciously, with the violent and erotic imagery on screen. Here, the director is playing a game of "film within a film," perhaps satirizing himself and his violent and erotic movie, asking the audience where the line between disgust and titillation is drawn.

Unfortunately for Alex, one of he films shown, seemingly images drawn from Triumph of the Will, as well as atrocity images of Allied bombings and Nazi concentration camps, is scored by Beethoven's Ninth. Hence, Alex can now not tolerate the most sublime, most perfect piece of music he has ever heard. The tragedy and irony of this underscore the bitter cynicism of Burgess' work perfectly.

Alex is brought before an assembly of the prison administration. What follows is a scene where an actor comes out on stage, and threatens, insults and physically beats him; and, when Alex attempts to respond, as is only natural to him, he immediately begins to become sick. Ipso facto, he is now transformed"; he is now incapable of ANY violent response. A similar thing happens when a topless model comes out on stage to tempt him. Reaching up to grab her breasts, he begins to gag and retch.

His conditioning is perfect. The tools of the State, the System, are most pleased. A resounding round of applause proves this; that is, until, the prison chaplain takes the staged, outraged.

Calling it a "disgusting display," he laments that the boy now has no "moral choice" in the matter of choosing non-violence, or even simple abstinence, and that this dehumanizes him. The Minister of the Interior assures him that "these are subtleties [...] The Point is, is that it works!" Everyone seems in agreement.

Alex is given a pack of his meager belongings and sent home. His "Pee and Em" (Sheila Raynor and Philip Stone) are less than thrilled to see their supposedly "cured" prodigal son return; sitting on the couch with Mum is Joe the Lodger, "munchie-wunching lomticks of toast."

The father tries to weakly explain that they've rented Alex's room to Joe, who is there "doing a job," and that they can't very well just kick him out now, can they? He had, after all, already paid next month's rent.

Joe has a more negative, harsh assessment: Alex has "made others suffer." Furthermore, he "doesn't deserve such a good mum and day." Also that, he "has you two to think about now [...] I can't very well go off and leave you two to the tender mercies of this young monster, can I? Who's been like no real son."

Alex begins to weep, lamenting not only the death of his pet snake, but the loss of his home and the seeming indifference to his plight by his parents. "Very well, you won't vide me no more!" he exclaims, and goes out, to ponder life in front of the same river or canal where he tossed his droogan companions at the start of the film.

A derelict, the very same one Alex and the Droogs beat-up at the start of the film, comes up to him begging. "Can you spare some cutter, me brother?" Alex gives him some change, only to have the old man recognize him. Quickly calling forth an army of leering, angry and aged homeless, they begin to beat Alex as he hurries away. Kubrick has a montage of close-ups of the derelicts mugging for the camera; but such faces are pulled numerous times in the movie, marking its over-the-top, comic-grotesque nature.

Falling to his knees in a tunnel beneath an overpass, his beating is interrupted by two policeman. And, to his shock and amazement, he finds himself face-to-face with Georgie and Dim--both of whom now, as Georgie says, have a "a job for two now of job age. The Police!"

The two Droogs-turned-peace officers take Alex into the woods, laughing as he begs for his life. They take him to an old rusted tub filled with water, a place they must have reserved for those individuals they deem, as officers of the law, worthy of being "roughed up." They half-drown and beat him, then walk away laughing, knowing they are completely safe in what they have just done.

Alex wanders in a beaten stupor until he finds himself walking past what should be a familiar neon sign--"HOME."

This is, oh tragi-comic turn of events, the home of the subversive writer, Mr. Alexander (Patrick McGee, who also famously portrayed that most famous of all subversive writers--the Marquis de Sade, in 1967's film adaptation of the famous play, Marat/Sade), who is now bound in a wheelchair, owing to Alex and his henchman's brutality. He is watched over by a massive bodybuilding bodyguard, played by David Prowse. The latter is busily benching weights when Alex, broken and battered, comes to the door, for once legitimately needing help.

Fate, as if to repay him for every evil he has ever committed, has him now a helpless, woebegone victim in the hands of one he has meted out horrific brutality to; yet, Alex recognizes that Alexander will NOT recognize HIM, as, when he was beating him and raping his wife, Alex was in disguise. Alexander does recognize Alex as the man he has just been reading about in the paper, the "victim of this inhuman new treatment."

Recognizing Alex's potential as a propaganda tool, Alexander laments that "we've seen it all before." That, "they are recruiting young toughs (such as Georgie and Dim) for the police", and that, soon, "they'd have the full apparatus of totalitarianism." He has his caretaker draw Alex a bath and prepare food, while he goes to call his fellow revolutionaries to come quickly for the opportunity that has almost literally, fallen into their laps.

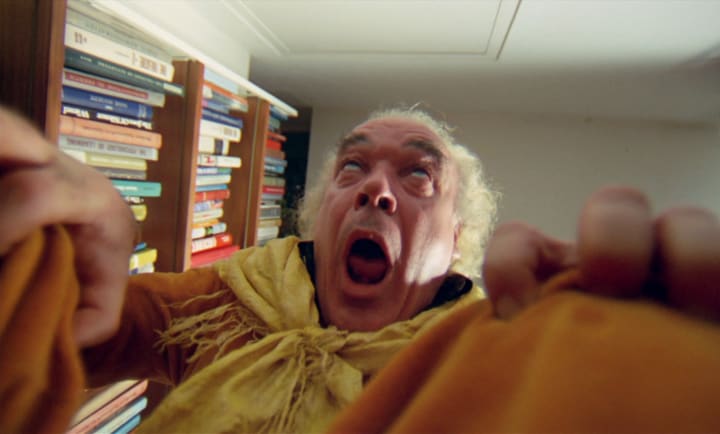

While relaxing in the bath, Alex makes the mistake of singing "Singing in the Rain" (a song whose irony underscores the plight inherent in the world of the film). Overhearing it, Alexander suddenly has the realization of who, EXACTLY, he has in his home, in his hands. His face, reflected in a mirror, his eyes rolling up into his head, takes on a hideous, grotesque, funhouse distortion.

Alex is fed a massive mountain of pasta; Alexander, now not quite so sympathetic, sits brooding menacingly before being joined by two of his comrades. They pepper their conversation with questions for Alex, who grows increasingly nervous, realizing something is up. He continues to eat, Alexander plying him with wine while explaining what has happened to his wife:

She was very badly raped, you see! We were assaulted by a gang of vicious, young, hoodlums in this house! In this very room you are sitting in now! I was left a helpless cripple, but for her the agony was too great! The doctor said it was pneumonia; because it happened some months later! During a flu epidemic! The doctors told me it was pneumonia, but I knew what it was! A VICTIM OF THE MODERN AGE! Poor, poor girl!

Finally, Alex passes out into his food, Alexander pulling his unconscious form up from the plate with utter contempt.

He awakes in Hell--or, at least, in Alex's own personal version of it. Beneath him, the three revolutionaries are blasting Beethoven's Ninth, the symphony Alex has been conditioned to hate, while, in an attic room directly above, he holds his hands over his ears in agony, beating on the floor, begging them to turn the hated music off. Finally, in desperation, he leaps from the window in an attempted suicide.

Meanwhile, the face of Alexander is shown in veritable religious reverie. He knows he is getting revenge on the one who has destroyed his life--and he believes he is doing it for just cause. (He is, however, a character as finally doomed to tragedy as all the others Alex has wronged.)

"I was cured alright!"

Miraculously, Alex does NOT die, but wakes up in the hospital with his arms in casts, in traction; he is fawned over by nurses, some of whom are having affairs with the doctor, and he is questioned closely by a psychologist with pictures he is supposed to describe. Based on his answers, we see that the fall has dislodged whatever conditioning the "Ludovico Treatment" provided him; it has now been reversed. He is, apparently, back to his old self.

The Minister of the Interior then stops by for a visit (after a visit from his weak, ineffectual parents), and offers him a job as a propaganda mouthpiece, feeding him steak, assuring him "we never wished you any harm!", and further informing him his death was to be used by Alexander and his anti-government friends to try and smear and bring down the system. "But," he says thoughtfully, "we put him away, where he can do you no harm!" (He never specifies just where they "put him away" at, under what conditions. Or if this is just euphemism for "executed.")

Giving a thumbs-up salute, Alex agrees to be the government spokesperson, as the Minister embraces him, and flowers and photographers are brought in. The final, comic image has him writhing beneath a nude woman, puzzlingly surrounded by men and women in Victorian garb. His final line of dialog, "I was cured, alright!" the comic icing on the cake for the entire preceding work; the film is about his personal evolution, from reprobate to victim of the state, and back again, in a world where "singing in the rain" is sometimes all we can manage.

Horrorshow

Note to any that may be fuming for me for revealing the entire film to them: this essay was written for those who have already seen the film. The question is not whether or not it should be viewed--by anyone seriously interested in cinema, it MUST be; I'm afraid my rather detailed synopsis, spoilers included, STILL are not sufficient to do this particular film justice. It is so integral a piece of cinematic history it is hard to imagine any serious aficionado of film failing to watch it, at least once.

The real question is: What does it all mean? To wit: At what price does society "reform" a man, when he is veritably stripped of identity, his ability to make moral choices, to "choose" to be "good" or "evil"? Alex, a psychopath, is turned into the most passive of all victims, karmically placed in the pathway of everyone he has seriously wronged. Is it society's fault he is a monster? His parents are weak, passive, as we said, ineffectual; the viewer perceives that they spoil him rotten.

By contrast, the government, society itself, seems to be flailing, trying to deal with the fact that, as the vagrant says at the start of the film, "there's no law and order anymore!" The inside of Alex's apartment building (bearing the charming name of "Municipal Flat Block A") bears witness to the vandalism and urban decay that must be infecting every level of the Clockwork Orange society--a bizarre mural on the wall is scrawled over, the elevator broken down, the floor strewn with cast-off bottles, trash, and debris. The government, "Big Brother," the surrogate parents of the entire country, seem to be flailing desperately to cover up the tendrils of societal rot.

The entertainment industry seems to feed it--vide the posters and sexual imagery the youth are bombarded with; but, also, of course, the fact that they drink milkshakes spiked with drugs. The adoption of the English-Russian hybrid language "Nadsat" almost suggests, on the part of Burgess, the cold war era fears of Soviet subversion. Is he slyly hinting that the reds, ultimately, are behind degenerate gang culture?

A language distances us from what we are using it against. Violence and killing is given less of a sting because of the euphemistic phrases used to frame them (such as the term "collateral damage," used to disguise civilian casualties of military bombardment). The language of Nadsat infantilizes life until it is one whopping, whooping good time; the most violent and sickening acts are "real horrorshow," and bear as little relation to reality, in the minds of the desensitized youth, as the images they "vide at the cine." Alex, taken with the sweeping music of Beethoven ("Ode to Joy" being yet another musical underscoring of the film's irony), finds himself visualizing the cinematic images of death, disaster, and even vampirism; i.e. that most emotionally move him.

The images he carries in his subconscious mind have of course educated him more than any school in modern times; we complain (actually know) that violent and erotic imagery desensitizes the viewer. The premise of Clockwork is that such imagery could conceivably be used the other way: to "reeducate" the incorrigible, violent criminal, and make him a placid, passive, even neutered "cog" in the machinery of the world--an easily manipulated non-threatening consumer, defanged and deballed, unable to hurt or offend anyone.

But, can such an individual ultimately survive in a dog-eat-dog world, one in which, at times, extreme decisions and unpleasant alternatives must be considered and acted on with quick passion and resolve--a world in which a man or woman must often struggle against overwhelming odds? At the least, how would such a person, conditioned to the point of self-destructive pacifism, ever hope to last?

In an old episode of Star Trek, one entitled "The Enemy Within," a transporter malfunction renders Captain Kirk two men: one a good, noble, but ultimately passive and spineless weakling, the other, an evil, menacing and psychopathic trickster who likes to go around slapping the miniskirt-clad backsides of female crew members. Ultimately, Kirk realizes he can no longer captain the Enterprise without melding back with his "other self." He seems to prove that man is a duality, both godlike and bestial, and that, ipso facto, one part of him, divorced from the whole, (his "dark side", as it were), is as essential as the other, the "angelic" noble and civilized half.

Similarly the predicament in which Alex finds himself: unable to fight by the end of the film, his victims and enemies are arrayed against him by fate, a turn of events he is now powerless to do anything about. The end of the does see him returned to what he was; as well as, we presume, a lover of Beethoven. Which was the original Alex though, and what the product of conditioning? His state of violent, criminal psychopathy? Or his later, weak, compliant and sheep-like state? Troubling questions.

Are lobotomies and electroconvulsive therapy humane? Today, we have the forced drugging of mental patients, and the widespread drugging of even small children by the psychiatric and pharmaceutical industry. All to bring about a flat, emotionless, and sterile response to a mad, mad, mad, mad world.

But of course, electricity, ice picks, and mind-melting, dangerous drugs are not, for the most part, necessary. Television and electronic mental manipulation are ALL that is required, via the propaganda vultures of the hack media, to program the greater part of the population; mostly through fear, guilt, and shame.

The People go along to get along. They'll do what they perceive the have to, simply to survive; as docile as a herd of computerized and catalogued drones.

You can anesthetize most of them to the grim, ugly, and ironic facts of their own mediocre existences. If they looked outside the box, for even a moment, they might become ruffled, dissatisfied. (Indeed, many of them, at this point, are). However, much as the conditioned responses of the test subject of the Ludivico Treatment, they'll begin to feel fear, to be sick, at the thought of turning away from the norm. The System demands, increasingly, that they obey; that they move around, like a "clockwork orange"; mechanical fruit that is, nonetheless, ripe to be picked and scarfed for the system's consumption.

This is their world, after all. (Isn't it?)

A place that could be described as even worse than "real horrorshow."

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.