Be Kind, Rewind: Why We Can Still Enjoy Classic Movies

Recently, there has been a boom in censorship in the arena of classic films, with appraisals of vintage flicks garnering them harsh reflective criticism from today's audience. While it's hard to deny the world has changed since their making, it doesn't warrant our dismissal of them. Here's why (and how) classic movies can still be enjoyed. [WARNING: There will be spoilers for the films mentioned in this essay].

In honour of its 40th anniversary of release, ScreenRant decided to release an article detailing why horror classic 'The Shining' (1980) has 'not aged well'. In this article, ScreenRant labelled the movie as one that is misogynistic and flippant towards such pressing and sensitive issues as familial abuse.

Some of them are valid points. Kubrick's 'The Shining' removed a great deal of Wendy's fight and vigor during the transition to the medium of screen, and Danny's fellow telepathic saviour Dick Hallorann does NOT die in the novel. In implementing these changes, Kubrick removed a great deal of heart from the story of the Torrances and the Overlook Hotel.

However, this arguably made for an all the more creepy film. This might be controversial to put out there, but 'The Shining' is one of the extremely few instances where I believe film trumps book. A lifelong fan of Stephen King, it pains me to say as much, but 'The Shining' delivers more chills in its celluloid form, because Kubrick erases the more feeling parts. This casts an uneasy, insidious, sinister tone over the entire film, one which is not broken by heartfelt interactions or happy endings. Instead, almost immediately we are thrown into an eerie world where only bad can happen.

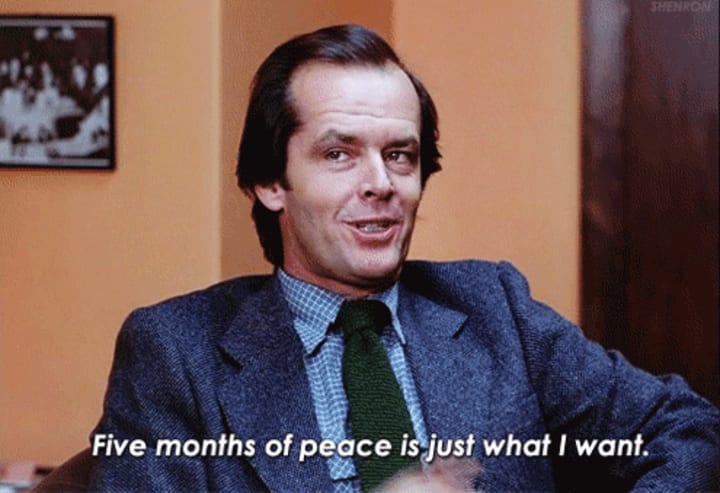

From the unsettling score to the sudden day-of-the-week title-cards, we, as the audience, are waiting with bated breath to see horror unfold. There is no respite from this. Everything in the film bears a grit-your-teeth plastic tone that signposts something unnatural dwells there. Even Jack Nicholson's Cheshire cat grin in the office of the Overlook's manager is a little too well-placed to be normal.

'The Shining' is certainly a film of its time, and Kubrick's uncouth treatment of actress Shelly Duvall onset is indicative of the movie being produced from the bowels of a time when female empowerment was, sadly, not as prominent an issue as it is today. Indeed, it is well-renowned that Kubrick wasn't the best actor to work with, reportedly bringing unstable actor to the point of mental breakdown during the intense filming of 'Doctor Strangelove' (1964). Then again, should we allow our perceptions of the film be swayed by behind-the-scene occurrences? While Kubrick's tyrannic treatment of his actors is unwarranted, ScreenRant's article pointed out problematic elements within the film that supposedly justify reassessment of this classic.

However, I think it is unfair to project our modern-day grievances upon films of the past. While they serve brilliantly to show how far humanity has come from the racially and sexually inept dark ages of cinema's beginnings, we should not dig in them ravenously for things that simply aren't there. We have a tendency now to dive deeply into films and place themes and attach meanings to them that may not have been the filmmakers' intention. Such is the subjective beauty of film, but, without caution, it may also be the viewer's downfall.

To say 'The Shining' excuses abuse by providing no consequences for it is... well, a reach. Jack Torrance, played to perfection by Jack Nicholson, is having his biggest weaknesses preyed on by the sinister energies that reside in the hotel, who are effectively using him as a pawn to get to the psychic powers within his son. But this isn't a green-light to feel sorry for Jack; he's struggled with alcoholism before, and has hurt Danny in the past. But what we can't forget, most of all, is the context within which this is all unfolding. This is a supernatural horror film - Jack is being manipulated by what are essentially ghosts to murder his wife and son. In the end, his son bests him in a clever maze trick. At no point does the audience member feel like Jack should win this round against his defenseless family. He is presented more bluntly as an axe-wielding maniac with his own demons to battle, after all.

Therefore, while there is a supernatural force underpinning Jack's abusive behaviour, the film does not glaze over the trauma it can cause. That simply isn't the part of the narrative that this film focuses on. That is one for the sequel, 'Doctor Sleep'. While Wendy is unfortunately made to be more submissive in the film version, she still holds her own against Jack and stalls him in his tracks. She does it, even, without help, if we count the film's decision to take well-meant hero Hallorann out of the equation. Therefore, Jack's behaviour is never excused or seen as 'justifiable'. Danny is the protagonist of the film and the audience is made to fear for him and his mother.

Our view of child abuse now is one of the utmost abhorrence and disgust, and while it was not as widely publicised or talked about during the release of 'The Shining', you have to examine its context before condemning it as archaic or insensitive. The boom of psychological and widespread media investigations into child physical and sexual abuse commenced four years following 'The Shining''s release, with the Satanic daycare scandal of 1984. However, four years prior, 'Carrie' (1976), another of King's adaptations, wonderfully detailed the abuse suffered at the hands of a dogmatically religious mother throughout one's childhood. The '70s was a progressive time for cinema, and while it was not the total shift required for full honesty and approach of serious topics, it was no longer shying away from sensitive topics.

Kubrick, although choosing a more supernatural route and removing some of the more human aspects from the equation, does not glorify or excuse abuse. He does not even gloss over it. When Danny returns from Room 237 with a bruise on his neck, we see the trauma the prior abuse caused in Wendy's accusatory reaction to Jack and Jack's rabid defensiveness. There is a deep-set scar gouged into their family structure, from which they can't recover - and the hotel knows this. It plays on it. Its sub-textual implications of such sensitive topics as abuse are there, they are just framed by a horror movie narrative and setting. Simply because 'The Shining' does not deal with abuse on a deeper level does not mean Kubrick's film should be condemned to the daylight-deficient VHS shelf forever. Whether you believe this is a mistake or not, the film should be remembered for the good it does, not its failings.

Indeed, the area which 'The Shining' admittedly does fall down in and ScreenRant neglects to mention, is its treatment of Dick Hallorann. King's novel has Hallorann survive the ordeal, but Kubrick throws in a curve-ball by having Hallorann die savagely by Jack's hand in the final act. Whether Kubrick's intention in doing this was to ramp up the fear-factor by leaving Wendy and Danny without the security blanket of another character to save them, it certainly provokes questions about the treatment of black characters in film, particularly horror. It begs the question: was Hallorann a necessary sacrifice, or did Kubrick view him as disposable? There is some room for thought here, and is likely the area of the film which causes the most discomfort when considering the path taken from book to film. It is the area which, I think, would warrant treatment of the film as having aged poorly, if one were to take that stance. I believe we can and should take issue with elements such as this, but to reappraise the film in such poor terms in its entirety? This is reductive.

Alas, in all this, I think people are missing the point. Movies, in all their superficial meanings and mistakes, are something we can look back at and learn from. If we watch 'The Shining' or 'Blazing Saddles', The Jerk' or 'The Return of the Pink Panther' with the notion in the back of our minds that 'this was made in a different time, some of this is no longer appropriate', then we remove ourselves from any potential damage they may cause. We can use their insensitive humour or deeply-embedded misogyny as springboards from which to view change. But always, we must contextualise them. To project our own values onto them, effectively ridding the movie of enjoyment, is to shy away from how far we've come. It is also a middle finger to some of the pioneering works of filmmakers who helped shape film as it stands today. Distance is needed to appreciate the more positive aspects of films in the past. Thankfully, considering how far we have progressed (in some respects - justice is still needed for Breonna Taylor), distance is one standpoint we are afforded with. So let's use it.

Movies, always indicative of their time, will continue to get things wrong. 'The Shining' may be dated, but its no less chilling than it was upon its release in 1980. While it doesn't focus on its deeper issues on a more personal and microcosmic basis, there are many films we can enjoy separately that do, on a very meaningful and confrontational plain. See such films as 'Mysterious Skin' (2004), 'Possum' (2018), 'I, Tonya' (2017) and 'Prisoners' (2013).

By re-imagining films as being subject to our progressive modern mindset, we are forgetting the more pressing issues of our own time, such as the Black Lives Matter movement and the Yemen crisis. Rather than projecting onto a dead past, we can learn from this crystallised error and ignorance while still appreciating the film as a manifestation of craft, an art-form. In the meantime, we can focus on the present dilemmas which we can proactively help shape, propel and resolve.

So, we can still enjoy movies if we contextualise them within our own history. This will allow us a little more opportunity to appreciate the innovation and craftsmanship behind the film reel.

Recently 'Friends' was heavily criticised by voracious Millennials who took to twitter to voice their issues with some of its less than tasteful jokes. Now, it must be said that when you watch it back, you cringe at how insensitive some 'Friends' jokes would seem if said in a sitcom of today. But here is where we contextualise and distance ourselves. By doing this, we can appreciate the stupidity of even thinking (at the time) that such a joke or comment was passable, while still allowing ourselves to enjoy the more successful elements of what we are watching. Rather than tearing old films down, we should spend our time lifting up and celebrating new films by black, BIPOC and female creators, whose voices have been notoriously and wrongfully quashed in cinema's historical mainstream realm of recognition.

If we did what ScreenRant did with 'The Shining' to every movie made prior to the year 2000 (and even some after that) then we would be low on viewing material. We can appreciate their faults from our own standpoint, but that doesn't mean these pre-progressive faults should overtake their brilliance, within reason. It is good that they make us feel uncomfortable upon reflection, but that does not render the entire movie inferior or unwatchable because of its content. We can't change time, but we can certainly change the way we look at things and learn from them. We shouldn't back down or lock those films away forever, we should confront them. For the medium of film, this is absolutely necessary.

About the Creator

Dani Buckley

Pennings of the dark and cinematic. Phantasmagoria abound.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.