Apocalyptic Mundanity- The Final 3 Films of Bela Tarr

A Take on a Master's Grand Finale by J.C. Embree

“Film is not about telling a story… It’s so we can get closer to people, somehow we can understand everyday life, and somehow we can understand human nature, how we are like we are.”

-Bela Tarr, in a 2001 interview about Werckmeister Harmonies.

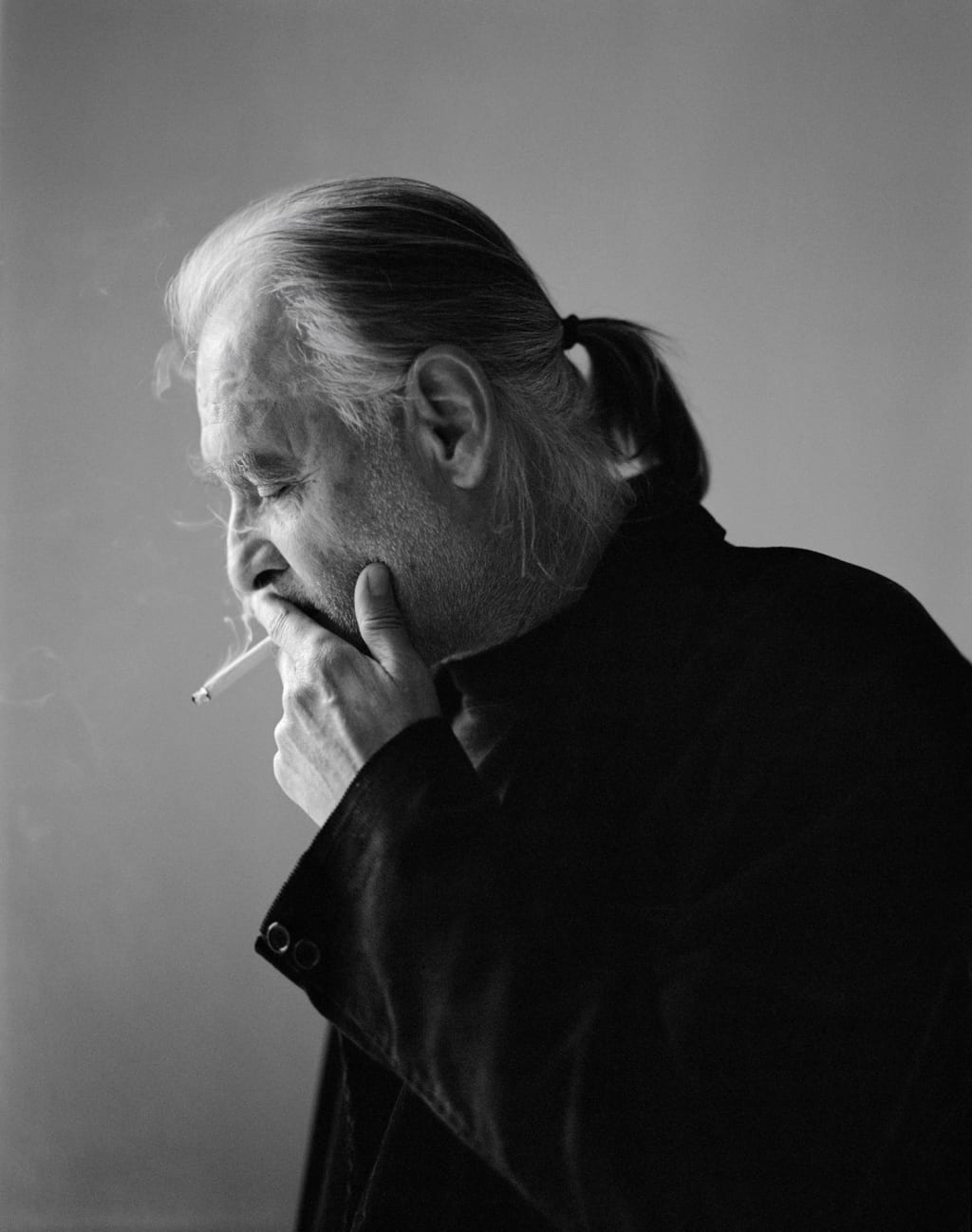

Bela Tarr, as of 2011, has (supposedly) retired from feature-length filmmaking. I didn’t discover Tarr until at least 2015, and at the time of this writing have only seen three of his films, the apparent last three of the Hungarian master’s career.

My first was The Man from London. I was strolling through an Alamo looking for yet another DVD to watch. I found the DVD, dug the contrast on the cover, and thought “I’ve heard so much about this Bela Tarr guy, and if Tilda Swinton wanted to work with him, he must be onto something.” I watched it within the next couple days, and while impressed by the monologous nature of the dialog and the lengthy takes, I felt very little. As I write this, however, I have just finished my first viewing of Werckmeister Harmonies, thoroughly impressed, and am hoping to re-watch London with older and more experienced eyes.

I’ve read that Tarr’s beginnings were characterized by a Cassavetes-esque cinema-verite style, although he claims even in this period that he had never taken in a Cassavetes feature, despite critical comparisons. Having had only seen his later work, such a vision would be surprising to this reviewer for his distinctive style in the second half of his career is a complete contrast to Cassavetes-- characterized by long Tarkovskian takes, a black-and-white look, and a greater interest in big monolithic questions than studying human interactions.

Werckmeister Harmonies, The Man from London and (especially) The Turin Horse are some of the most pessimistic films I’ve seen in my twenty-five years. They meander but are not plotless, most glimmers of hope are snuffed out, and many of its characters could be simply described as “doomed.” I will write about these films not in order of Tarr’s chronology, but in the order in which I viewed them.

Few stories are both as simple and enticing as the premise of The Man from London. A pointsman (Miroslav Krobot) witnesses a violent altercation that results in an abandoned briefcase filled with banknotes. He retrieves the briefcase, hoping it carries not only financial answers but the future that many blue-collars dream of. Rather than the snappy dialog and gangster-filled melodrama of an old-school noir, however, we are granted a web of characters, either associated with the pointsman or with the briefcase, showing the consequences and dilemmas that all correlate to his taking of the briefcase; it is depicted through multitudes of dialogs and moral conflicts.

It is here that I recognized Bela Tarr was more interested in making his audience think as opposed to simply entertaining us. Having heard all the comparisons to Tarkovsky, I was not terribly surprised. And, while intrigued, I do believe I found a certain pointlessness (other than the point of “showing off” in the six-or-seven-minute takes and characters who always walk as though they have nowhere to be. Nevertheless, after tonight’s screening of Werckmeister, I believe something clicked between this viewer and the work of this director that warrants a revisiting of London.

About a year later, I rented another film from Alamo. Another Tarr film by the name of The Turin Horse. Much more objectively nihilistic and depressing, it depicted a farmer and his daughter in a post-apocalyptic environment, where they seem to be nowhere. We don’t know what happened before the film, and our ideas about what happens after the credits roll are not terribly optimistic.

Much of The Turin Horse is entirely unexplained, but upon viewing it, I understood that a certain ambiguity was exactly what Tarr wanted. And it’s not about trying to interpret the answers; it’s about how little the circumstances surrounding these questions truly matter in the first place, as the result is always the same. The farmer and daughter are circling the drain, and their efforts are simply irrelevant.

As mentioned, I watched Werckmeister Harmonies in this last hour, and was thoroughly impressed, now citing it as my favorite. In an unspecified time and place of Communist Hungary, a supposed “circus” consisting of a small group with a dead stuffed whale in tow visits, causing suspicion and eventually violence within the already-hellish landscape of Tarr’s vision.

It opens in a long take of mundane beauty, where Janos (Lars Rudolph), an artistic young man, recites a small poem in a tavern while orchestrating a parallel dance between the patrons. This is the closest thing to a delightful moment that Tarr is going to grant us. In terms of optimism, it’s all downhill from here in a mystifying take on mob mentality and the levels of depravity that can be found in a world of small-town anonymity.

Bela Tarr seems to have several recurring collaborators, two of which I’d like to acknowledge-- novelist Laszlo Krasznahorkai and editor (and wife of Tarr) Agnes Hranitzky. Krasznahorkai has contributed to every Tarr film I’ve seen, having written the book that would become Werckmeister and co-writing all three scripts whereas Hranitzky has not only the editing credit but also a co-directing credit for all three of them.

While I always tell people that I respect filmmakers who write their own scripts more, anyone could easily admire the collaborative marriage between Tarr and Krasznahorkai, for while I am yet to read a Krasznahorkai novel, the consistency of their output implies a respectful and dignified partnership, one where we can surmise that the two share similar visions of the world that play off each other and create a thematically rich but consistent artistry that cannot help but be admired, even by detractors of Tarr’s directorial efforts. If you hate the final three films of Tarr, you still manage to get the vaguest of insights into Tarr’s soul, and its putting into words was greatly helped by the postmodern novelist Laszlo Krasznahorkai.

Hranitzky, who has a more literal creative marriage with Tarr, began as his editor, then as his wife, and finally would co-direct the last three films of Tarr’s career. Apparently her credit as co-director stemmed from her need to constantly be on set to assist with Tarr’s several-minute takes, whereas her vision likely seeped into his, which paired with Tarr’s authoritative perspective and Krasznahorkai’s literary talents, create works of unmatched harmonious quietude.

Many of the defining factors of these three films are the hopelessness of existence that its protagonists endure. The pointsman in London will feel like a wreck or look like one, no matter what he does with the briefcase of blood-money; most people are dead in Turin and its protagonists days are numbered; and the singular young Janos of Werckmeister proves incapable of swaying the proverbial mob in the film’s climax. Tarr’s films could be called “tragedies” by some, but that would imply that there was some hope to begin with. We don’t see the characters as people who were ever truly elated or overjoyed, they have just existed up until this point, not truly living. It’s a director’s job to play God to their characters, and instead of Tarr granting a call to adventure, he grants a nihilistic reality check.

None of the landscapes are picturesque, either. From what I’ve observed they are all seemingly ruined locations, as if to externalize Tarr’s morally ambiguous characters. And they are not established as Ozu-esque “pillow shots” either. Many of Tarr’s lengthy sequences are simply people walking and drifting, doing minimalist tasks and going about their day. These sequences entrap us, and cause us to realize that the meaningful parts of life are all tied together and connected by much longer and more tedious bouts of meaningless.

The consistency of the black-and-white aesthetic contributes much to this pessimism. Tarr’s world is as desolate as it is colorless, making trudging through a twelve-minute take of a man riding a cab and beating his horse all the more merciless. Tarr’s films are not things we go to for entertainment, but to experience things of depravity until we feel numb to them. It’s more effective in doing this than the vast majority of horror films, at the very least. A Bela Tarr film is not something you watch- it’s something that happens to you.

There’s a lot more to consider when you understand Turin as Tarr’s final film. Few filmmakers would make such a bleak film, even in their early fifties, and then announce a permanent retirement. Many may ask “Is this what he’s leaving us with? Why?” One could even interpret Turin as Tarr paying tribute to his own work, as the film feels like a three-hour concoction of all his thematic ideas and personalized tropes crammed into a single feature.

One important thing to realize, however, would be Tarr’s own interest in Friederich Nietzsche, and the story that surrounds the final days of Nietzsche, whereas apparently, after witnessing the brutal beating of a horse by its owner, Nietzsche went into hysterics and went under familial care, never again saying a word, save for “Mother, I am stupid.” This is addressed in the film’s opening. The Turin Horse takes the perspective of the farmer that Nietzsche witnessed, and whose story is filled with Tarr’s own ideas.

This could imply a multitude of things- it could be Tarr’s way of defining perspective, giving a man who’s only fame (or notoriety) stemmed from causing a psychotic break from a philosopher a more well-developed story of his own miseries. The apocalyptic setting the farmer and his daughter endure could be seen as a literal “death” of God, which Nietzsche is known for proclaiming. Perhaps it's simpler though, just showing the inevitability of our own demise, whether you achieve acclaim or notoriety, the result is always the same.

Nevertheless, Bela Tarr has not retreated into a reclusive state (as one may predict). He has since directed short films, but his most captured moment in the spotlight likely came from the film and actions of China’s novelist/filmmaker Hu Bo.

A protege of Tarr, Bo, an established young novelist, would go on to write and direct An Elephant Sitting Still in 2018. I have only seen parts of it, but when I take in the whole film I hope to review it. In these small portions, however, one can see a clear Tarr influence in the length of the tracking shots, and the way the camera glides and zooms slowly and gracefully.

Hu Bo would commit suicide shortly after the film’s completion, whereas Tarr would become emotional in presenting the film to international audiences. Say what you will of the lack of emotion in the art of Bela Tarr, but the same cannot be said about Bela Tarr the man.

About the Creator

J.C. Traverse

Nah, I'm good.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.