“When a man gives his opinion, he’s a man. But when a woman gives her opinion, she’s a bitch.” (Bette Davis, quoted in Rachel Abramowitz (2000) Is That a Gun?)

Bette Davis made a career out of playing women with a purpose. So, she is a good place to start in thinking about my own intent when I write about movies and movie stars.

Writing about films, like having an opinion, can also be split along gender lines. Are you a gossip or a Hollywood reporter? Are you a film critic or a bitch?

For Hollywood to work, it needs not only to produce films, but it needs to be written, spoken and gossiped about. It needs approval and dissenting voices.

Hollywood deals in myths of success, excess and failure. It’s sleaze, misfortune and bad behaviour are important parts of its mythology. The Hayes code demanded behaviour on-screen that was rarely imitated off-screen.

In Hollywood, to be a success you don’t just need to make money, you need to be talked about. And therefore, gossipers become powerful. They are part of the myth-making machinery. Gossip matters.

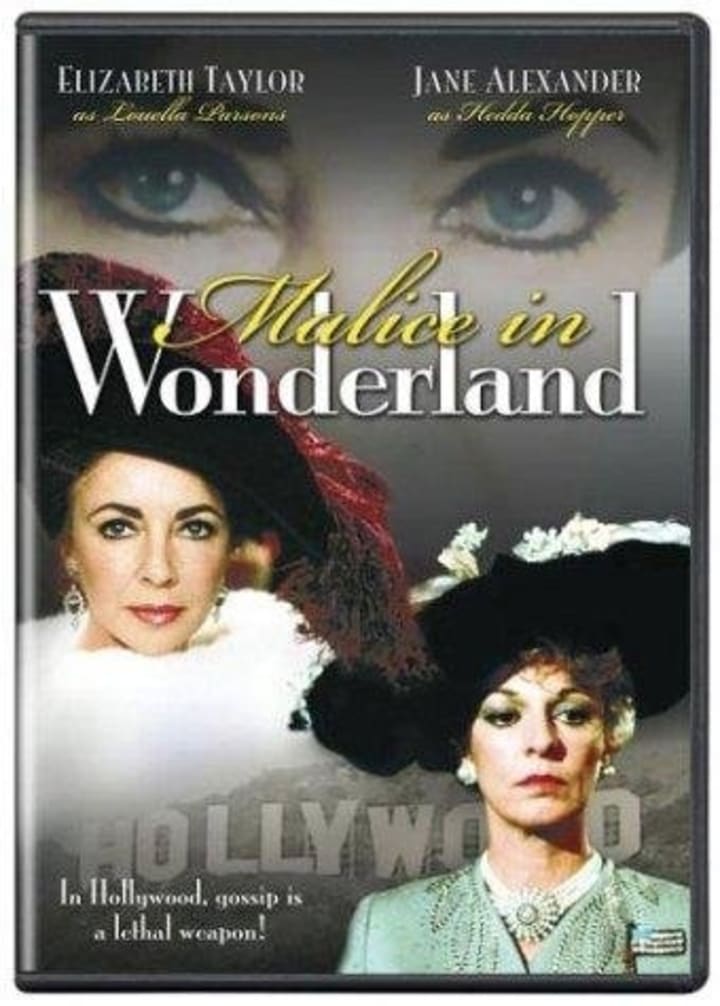

The most famous Hollywood gossip columns belonged to two women, Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper.

Tony Curtis is quoted as saying:

“You only knew how good you were doing by your appearances in their columns. There was no other measure.” (Vanity Fair, 2016)

Their power and influence to make and break stars can be seen in the press treatment of Ingrid Bergman. Bergman was known on-screen as saintly. She had been cast at Sister Benedict in The Bells of Saint Mary’s, and this casting was partly down to Hopper’s backing of the star. Bergman then went on to star in Joan of Arc. Bergman as religious, chaste and saintly was firmly established as part of her screen persona. However, in 1950 Louella Parson’s scoop that Bergman was pregnant with the child of the film director Roberto Rossellini appeared on the front page of the LA Examiner. Both Bergman and Rossellini were married to other people at the time. Furious that Parsons got the scoop on the Bergman/Rossellini affair, Hopper began a vicious smear campaign against the Swedish actress. The resulting backlash meant that Bergman’s films were boycotted by the American public.

Parsons and Hopper were famous for the stories they broke, but also for the secrets they kept. Neither of them reported on Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn’s affair, or gossiped about Norma Shearer’s dalliance with Mickey Rooney. It is thought that much of their power came from what they knew and didn’t tell. (Louella Parsons was on Hearst’s yacht the night Thomas Ince, a renowned director and producer died in mysterious circumstances). In Hopper’s case, power also came from her role on the House of Un-American Activities Committee and her fervent attempts to uncover and name anyone suspected of communist leanings.

The feud between the gossip-mongers became a Hollywood myth and a TV film called Malice in Wonderland, starring Jane Alexander as Hopper and Elizabeth Taylor as Parsons.

They gossiped with intent. Their intent was to support themselves and their own excesses, but also to exert power.

They may have had power and influence, but they were not well liked. Because of course, gossip is not a great word to be associated with. Gossip is idle chat, rumour, trivial and possibly malicious. Being a gossipmonger may make you feared and courted, but it is also tasteless. It possesses none of the panache of the critic, who demonstrates erudition and fine judgement.

It is, apparently, thanks to critics, that we develop an understanding of what makes good cinema. When I first started writing about film, as a Drama undergraduate with a peculiar obsession with 1940s and 1950s movies, I read a lot of Pauline Kael. My dissertation was about the wonderful Doris Day and Kael had written about the Doris Day routine “of flirting with bed but never getting there…”

Kael’s writing was witty, sharply observed and placed an emphasis on the experience and emotions of a film. However, as I got serious about film, I was led to believe that this wasn’t how serious critics wrote. Pauline Kael was often eschewed by more scholarly writers for not following rules or applying theory. So whilst she was an influential writer, she was not supposed to be taken as a serious one.

And is this sexism raising its head again? Quite possibly.

As Helen O’Hara says (2021):

“If female critics have never been entirely alone, as female directors like Ida Lupino or Dorothy Azner were, often we’ve been alone at our publications. Being in such a minority is odd. You’re often challenged on your knowledge and have to prove your familiarity with the canon of films accepted as great cultural or commercial touchstones – almost all of them male-led and male-directed.”

A 2018 study released by the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that women made up just 21.3% of critics who reviewed 300 top movies between 2015 and 2017. The figures for women of colour were woefully low at 3.7% of the total profession. This means that the people who tell us what matters in the movie world are mainly white men, commenting on white, male-led films.

I’ve started writing about film again. In the last month I have published two blogs on Faith Domergue and Sondra Locke.

So, what am I? Am I critic or am I gossip? Certainly the blogs are as much about the stars’ private lives as their screen careers. But gossip is not my intent.

What led me to write about these two came from a sense of discomfort. They were both employed to tell stories as actresses and in Sondra’s case as a director. And yet they had little control over the way their own stories were told. Both had been subjected to abusive relationships with powerful men that had provided for and then sabotaged their creativity. When I read about them I was haunted.

I don’t mean that I was visited by their ghosts. Anthropologists Spooner-Lockyer and Kilroy-Marac (2021) argue that where there is history there is a haunting. That haunting is about a history that needs to be acknowledged. And that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to acknowledge these women as they were, but also as what they might have been had their stories been allowed to flourish and their talents more fully explored.

And I’m going to keep exorcising those ghosts.

I want my joy of watching old movies and reading film history to fuel my creativity. Recently, watching Now Voyager, I became a little obsessed with the child actress Janis Wilson who plays the part of Tina. It is an affecting, promising performance. But the actress only made five films, retiring at 18, and she suggested that she wasn’t being cast because she didn’t photograph well. And that makes me sad. Because she could act. Hell, Bette Davis thought she could act.

And not every story has to be told by a picture perfect face. Janis must have had stories to tell. One of her quotes on IMDB reads:

“I am the last surviving witness to the filming of Casablanca (1942), which was being filmed on the set right next door. I used to slip over there and watch it.”

She would have been 12 at the time. I would love to know what that experience would feel like from a 12 year old’s perspective. It may well become a short story.

And that is what I mean when I say I’m a ghost-writer. I want to take my hauntings and obsessions and turn them into questions to be answered and new stories to be told. I want to open up conversations about the way women’s stories are told and who gets to tell them. That is my intent.

Can you imagine?

What might it look like if we shifted the lens and looked at women’s stories seriously and with compassion?

What if the waif-like, wispy presence of Sondra Locke had ever directed the sultry, feisty Faith Domergue?

I would watch that movie.

My intent is to offer a parallel universe where contributions of the marginalised are celebrated. So, watch this space for a mix of gossip, critiques, ghosts, real-life and imagined stories.

About the Creator

Rachel Robbins

Writer-Performer based in the North of England. A joyous, flawed mess.

Please read my stories and enjoy. And if you can, please leave a tip. Money raised will be used towards funding a one-woman story-telling, comedy show.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.