A cultural history of gaslighting

As recognition of psychological abuse grows, Arwa Haider explores how the issue has been portrayed in popular culture since the early years of cinema.

In her Oscar-winning performance in the 1944 movie Gaslight, Ingrid Bergman plays a young opera singer, Paula, traumatised by the death of the aunt who raised her, but swept into a whirlwind marriage to a charming musician (Charles Boyer). We watch as Paula becomes increasingly isolated and disorientated, convinced by her husband that she is losing her mind: items disappear; strange noises seep from a locked attic; the gas-fuelled house lighting mysteriously fades and glowers. We realise, before Paula does, that it is her husband creating these head-spinning disturbances; in one scene, she entreats him: “Are you trying to tell me I’m insane?” Her husband retorts: “Now, perhaps you will understand why I cannot let you meet people.”

‘Gaslighting’ – meaning psychological abuse, where the victim is led to doubt their own judgement (and sense of reality) through the abuser’s repeated denials, deflections and lies – is often treated as a modern buzzword, although it has appeared in decades of psychoanalytical studies. The term actually stems from the above period thriller, itself based on Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play, and a 1940 British film; each of these versions presents an intense, intimate picture of domestic abuse, even while the subject was a general taboo. Ironically, the Hollywood remake tried to suppress its predecessor, by demanding that all prints be destroyed; a profit-driven entertainment biz is rarely ‘moral’ at heart. Yet mainstream drama has a unique potential: to engage huge, diverse audiences through storytelling; to portray what happens behind closed doors; and to shape our awareness of domestic abuse. While it’s clearly a universal issue, US and UK drama depictions have had a massive mainstream impact on how it’s understood.

In a ‘golden age’ of 21st-Century Western drama, there also seems to be a gradual awakening: that this is a universal issue, affecting all generations, genders and backgrounds (though in the vast majority of cases, the victims are female and the perpetrators male), and that seemingly ‘subtle’ forms like gaslighting and coercive control are devastating in their effect. There are impressively nuanced portrayals in successes such as HBO’s Big Little Lies (adapted from Liane Moriarty’s 2014 novel), where the apparently glamorous marriage of Celeste and Perry (played by Nicole Kidman and Alexander Skarsgård) conceals brutally ugly truths, with far-reaching consequences. The Netflix miniseries Unbelievable (inspired by a report on real-life rape cases) reflects how victims of abuse face gaslighting from the justice system itself. The much-loved, long-running British soap opera Coronation Street handles an ongoing coercive-control storyline with crucial sensitivity.

Entering the mainstream

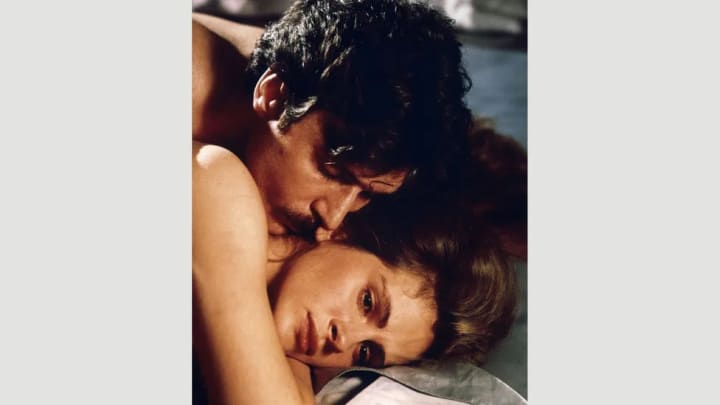

These vital shifts have been a long time coming. While post-war drama brought more open-minded attitudes to social issues (Ken Loach’s 1967 film Poor Cow, based on Nell Dunn’s novel, depicts a working-class woman locked in a pattern of abuse), a turning-point came later, prompted by key social and legal changes. Much of this progress is incredibly recent; Britain’s first women’s refuge opened in 1971 (in west London, founded by Erin Pizzey, whose organisation became the modern charity Refuge), and marital rape was first recognised by UK courts in 1991, and became a crime across all 50 US states in 1993 (the US National Domestic Violence Hotline took its first call in 1996). In 2015, UK laws effectively criminalised coercive control as domestic abuse.

These films deny the many complexities and contradictions of abuse, to which there are no easy Hollywood solutions – Diane Shoos

Over the 1980s and ‘90s, domestic abuse became a prevalent theme in mainstream film and TV drama. Many featured high-profile performances, such as Farrah Fawcett in TV movie The Burning Bed (1980, based on the true account of battered wife Francine Hughes); Julia Roberts in Sleeping With The Enemy (1991); Angela Bassett in the Tina Turner biopic What’s Love Got To Do With It? (1993); and Kathy Bates in Dolores Claiborne (1995, based on Stephen King’s novel). Blockbuster plots, with a focus on explosive physical violence, sparked public discussion, but they also created a strange disconnect; they lulled viewers into an illusion that domestic abuse was something that happened to other people.

As Diane Shoos writes in her book Domestic Violence In Hollywood Film: “Despite the fact that these narratives seem to sympathise with their protagonists and challenge myths about domestic violence, most offer all-too-comfortable positions from which we can ‘see’ what we already assume about men as abusers, women as victims, and the racial and class politics of violence…. These films deny in turn the many complexities and contradictions of abuse, to which there are no easy Hollywood solutions. Most seriously, they propose that abused women can and must singlehandedly solve ‘their’ problem.”

“Popular culture can be a really great way of educating mass audiences. But dramas in the 1990s reinforced the limited views and myths around domestic abuse: that it only happens to a certain kind of person; that ‘he only did it because he was drunk’,” says Lisa King, Refuge’s Director of Communications and Campaigns. “The conversation has actively evolved.”

King highlights the gaslighting storyline in BBC radio soap drama The Archers (during which character Helen Titchener was subjected to slow-burning coercive control by her husband) as a pivotal moment: “The Archers built that storyline in real time; it addressed misunderstandings like ‘Why doesn’t she just leave?’ and built knowledge about what domestic abuse is: the financial side, the sexual side, jealousy and possessiveness, having your reality distorted. It lifted the lid on a situation where women have been blamed and isolated, and reached a demographic that really engaged with it. The characters are identifiable.”

Shaping the story

In February 2016 (while The Archers storyline was well underway), calls to Refuge’s helpline increased by 17% compared to the previous year. In that same month, Archers fan Paul Trueman set up a JustGiving fund to help real-life victims of domestic abuse; by 12 May 2016, the fundraising page had raised more than £150,000.

Refuge’s team works with an array of scriptwriters to enhance understanding, from soap operas to series such as Big Little Lies and films including Tyrannosaur (2011), which features an extraordinary performance from Olivia Colman as Hannah, a victim of horrific abuse by her husband. Colman subsequently became a Refuge ambassador and patron of youth-focused charity Tender.

Communication between real-world specialist services and film/TV teams doesn’t merely produce stronger drama; it extends a lifeline. Coronation Street’s current gaslighting storyline, in which vivacious Yasmeen Nazir (Shelley King) is psychologically abused by her partner Geoff (Ian Bartholomew), was developed over two years, with guidance from Women’s Aid and local Manchester charity Independent Choices.

Often, it proves more of a challenge when perpetrators find someone with confidence and spirit, who they are able to slowly diminish over time – Amy Coombs

“In many ways psychological abuse is still so misunderstood, so we felt we should use our platform to help people identify toxic behaviour patterns, and develop a deeper understanding of how this sort of relationship manifests,” explains Corrie’s senior storyliner Amy Coombs. “It felt right to play this with a character like Yasmeen because she is such a bright character. We found from research that perpetrators don’t necessarily choose victims they believe to have low self-esteem. Often, it proves more of a challenge when they find someone with confidence and spirit, who they are able to diminish slowly over time.

“The biggest challenge for us was the pacing of the story,” admits Coombs, pointing to the usually snappy resolutions of soap tradition. “It had to be a slow burner due to the nature of this type of abuse – the control doesn’t just happen overnight, and it is often disguised with charm, love and romance in the early stages. We needed our audience to invest in Yasmeen and Geoff’s relationship in the early stages, otherwise they wouldn’t have felt the impact of Geoff’s abuse later on; nor would they have understood why Yasmeen was sticking around. We’ve worked hard to build him up as Mr Joker to the outside world; quite often when perpetrators are identified, the consensus is: ’Not him? But he was such a nice guy!’”

Coombs has been heartened by the public response to the storyline: “Whether it encourages women to identify certain patterns in their own relationships, or helps others reach out to their sisters, brothers, friends, mothers or neighbours if they think they might be suffering, we will have done our job if it helps even one person escape a mentally abusive relationship.”

Another distinctly relatable portrait of gaslighting came in 2019’s I Am Nicola (part of a dramatic triptych by British writer-director Dominic Savage), starring the brilliant Vicky McCLure (This Is England; Line Of Duty) as a hairdresser stifled by her toxic relationship. This captures the often deceptively mundane nature of domestic abuse, and its creeping oppressiveness; there is no ‘Hollywood ending’, but there is an exhilarating note in its final scenes – and Savage believes that drama can effect positive social change.

“If you can make something that so many people are actually experiencing on a day-to-day basis, that they can properly relate to and feel emboldened by, inspired by, and want to make changes to their life for the better, then it’s the best reason to be creating work,” he says.

Bursting the bubble

There is anticipation surrounding the independent British short Losing Grace, created by a multi-award-winning all-female team, and supported via crowdfunding. This ‘poetic thriller’ will be filmed on the Isle of Man, and blend realist drama about the aftermath of domestic abuse (and its impact on children) with Manx folklore (the mist that shrouds the island; the historic Tower of Refuge off its coastline).

“We were predominantly looking at the relationship between a mother and daughter, and that line of protectiveness,” explains writer-director Athena Mandis. “What if everyone sees the mother as ‘mad’, but she’s actually running away from an abusive relationship? To find yourself in a position where your work is resonating before it’s even made, is humbling. People definitely respond to seeing themselves represented; ‘I’m not in a bubble; this is not OK’. If we’re not having the conversation, then we’re not going to impact change.”

About the Creator

Many A-Sun

Where your interests lie, that's where your abilities lie.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.