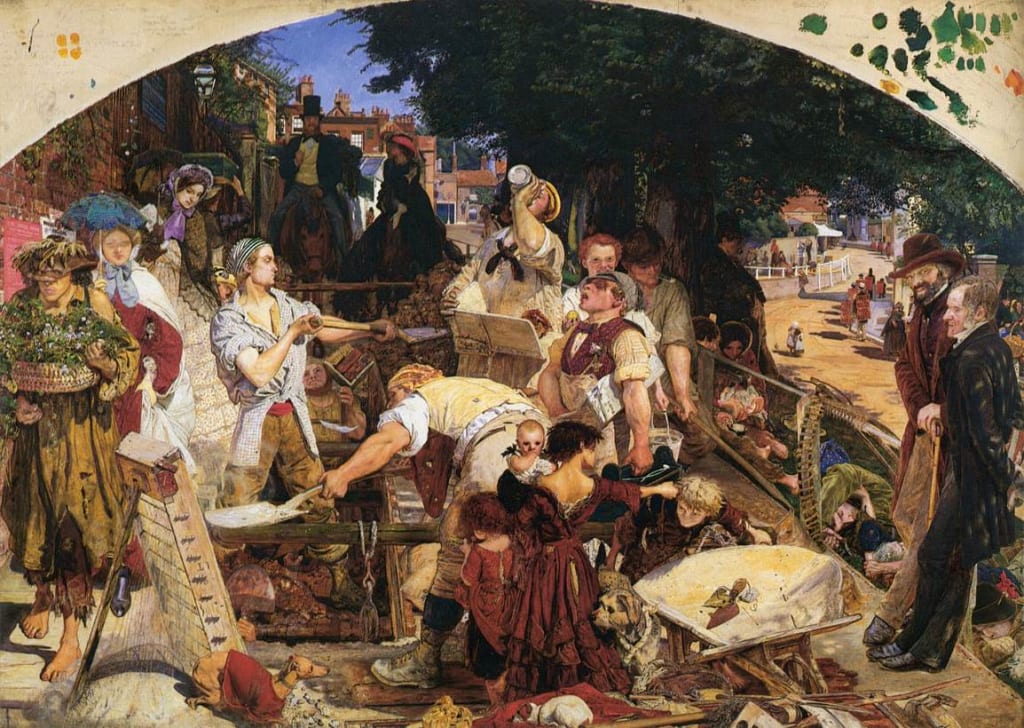

"Work", by Ford Madox Brown

An artwork with a moral message that acts as a commentary on Victorian class attitudes

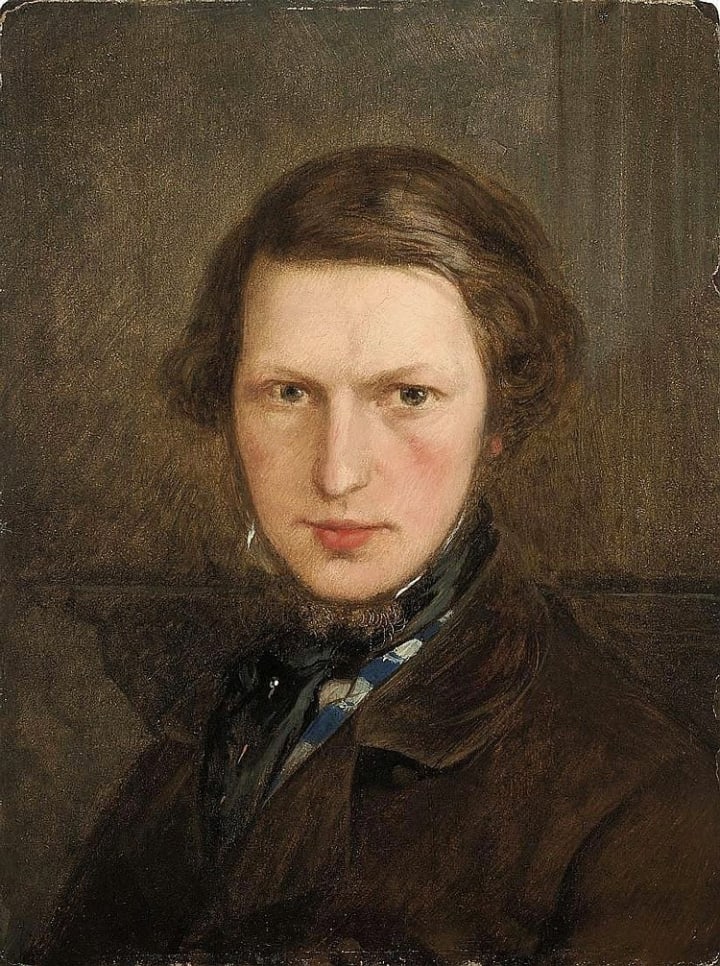

Ford Madox Brown (1821-93) was born to British parents in Calais, France, his father being a retired ship’s purser. He gained his training as an artist in Belgium and France and only settled in London in 1844.

He was closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Brown’s use of bright colours and choice of romantic themes from English history and literature was a strong influence on his younger contemporaries. In return, their emphasis on objective realism, as opposed to Victorian sentimentality, influenced his own work. His 1865 painting “Work” is a good example, as it incorporates truthfulness to nature with a moral message, but whether it avoids the sentimentality curse is open to question.

On a superficial level, “Work” is a busy scene of workmen in a north London street, working on the installation of a new sewerage system while being watched by a motley collection of onlookers. However, it is also a moral message about the value of labour to the human condition and it embodies the basic Victorian theme that work is always preferable to idleness, although this message was applicable mainly to the “lower orders” who could thence be divided into the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor.

Brown began the painting in 1852, but laid it aside for several years as he was never well-to-do and needed to be assured of a buyer before he was willing to complete it. The patron who eventually came along was Thomas Plint, a wealthy stockbroker who bought many works by the Pre-Raphaelites but who was something of a double-edged sword in that, although he paid in advance instalments and therefore provided the artists with a regular income, he was also inclined to demand that changes be made to the paintings as they progressed.

In the case of “Work”, Plint wanted the moral message to come through more strongly than Brown had originally envisaged. The painting therefore includes a woman handing out temperance leaflets and has the writer and thinker Thomas Carlyle observing the scene. Unfortunately for Brown, Plint died in 1861 (aged only 38) and Brown was not the only artist who ended up out of pocket before their paintings could eventually be sold.

Brown went to great lengths to explain the painting in detail so that the message would not be lost, and these explanations might perhaps detract from the viewer’s experience of seeing the painting for the first time and working out the meaning for him/herself. However, Brown clearly admired the “honest worker”, two of whom are the central figures of his composition, and his comments, patronising though they are, are evidence of his hero-worship:

“'Here are presented the young navvy in the pride of manly health and beauty; the strong fully developed navvy who does his work and loves his beer...'

Also portrayed are a workman who is drinking from a bottle, and a beer-seller. Brown’s comments suggest that the latter has suffered a black eye from a fight with a gin drinker, which is an interesting take on William Hogarth’s 18th century “Beer Lane” and “Gin Alley”. Beer was seen by both artists as a healthy drink, which it undoubtedly was by comparison with the water that was often unsafe to drink in cities like London, even in Brown’s time. The work on London’s sewers, pictured here, was part of the move towards providing safer water for the capital’s growing population.

Passing by the scene, or watching it, are a variety of north London residents, including a bare-footed flower seller (although the feet are remarkably clean!), a rich lady with a parasol, two wealthy people on horseback whose way is blocked by the hole in the road, the distributor of temperance leaflets mentioned above, and a girl who is trying to keep her younger brother in order while holding her baby sister.

On the right are two “brain workers”, in Brown’s words, “who seeming to be idle, work, and are the cause of well-ordained work and happiness in others”. These are the writer Thomas Carlyle and Rev F. D. Maurice who founded the Working Men’s College where Brown gave lectures in art. Maurice was painted from life but Brown used a photograph for the image of Carlyle.

Brown’s notes also make very clear his acceptance of the structure of Victorian society. His comments on the people on horseback read:

“This gentleman is evidently very rich, probably a Colonel in the army, with a seat in Parliament, and fifteen thousand a year, and a pack of hounds. He is not an over-dressed man of the tailor's dummy sort - he does not put his fortune on his back, he is too rich for that; moreover, he looks to me an honest true hearted gentleman.”

The viewer is not therefore meant to draw any conclusion from the fact that rich people are able to be idle, or to conclude that their lack of work demeans them in any way. It is only the “working class” for whom work has a moral purpose. This is a typical Victorian attitude, as summed up in a verse from the children’s hymn “All Things Bright and Beautiful” (written by Cecil Frances Alexander in 1848): “The rich man in his castle, The poor man at his gate, God made them high and lowly, And ordered their estate.” This verse is usually omitted from modern hymn books but would not have seemed out of place to the people who first sang it, or to Ford Madox Brown.

As if to emphasise the class structure, and the correctness of it in Brown’s eyes, the top of the painting is domed, with the rich couple on horseback occupying the focal point of the dome. They are placed at a higher level than the workmen, with the poorest people being at the front and the lowest level. The very lowest level is occupied by three dogs, and even here there is social stratification from a whippet wearing a red coat to a rough mongrel which accompanies the group of poor children in the foreground.

Brown’s painting therefore seems to mimic the structure of many medieval religious paintings, often domed to fit a cathedral wall or reredos, in which God is at the top, saints in the middle and mere mortals at the bottom. “Work” can therefore be seen as reinforcement of the Protestant work ethic, in that the moral message is also a religious one.

Apart from Rev Maurice, Brown used real people (as opposed to models) for several of the figures, including the workmen. One of the latter was killed in an industrial accident before the painting was completed.

Modern attitudes to this painting will be very different from those of its first viewers, because people in 21st century Britain are not as wedded to the class system as were the Victorians, and the assumption that the “working class” must do hard physical work for the good of their souls, whereas middle class people need only use their brains and the upper classes are freed from either form of labour but are divinely ordained to rule over the rest, is one that is abhorrent to most people today.

“Work” is therefore an excellent portrayal of past social attitudes, and should be regarded in the context of the times when it was painted.

“Work” is quite a large canvas, at 54 by 78 inches (137 by 198 centimetres). It may be seen in the collection of the Manchester Art Gallery.

About the Creator

John Welford

I am a retired librarian, having spent most of my career in academic and industrial libraries.

I write on a number of subjects and also write stories as a member of the "Hinckley Scribblers".

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.