What is Existential Philosophy?

An Introduction

Existentialism is one of the most popular and intense ideas of modern philosophy riddled with problems and puzzles that philosophers since the 19th century have been trying to rationalise and solve. The Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy defines existentialism as ‘a catch-all term for those philosophers who consider the nature of the human condition as a key philosophical problem and who share the view that this problem is best addressed through ontology.’ (Burnham, D. Papandreopoulos, G.) It is also mainly concerned with action, that a meaning to a person’s life can only be found in what they can do and what they have done - it states ‘My existence consists of forever bringing myself to being - and, correlatively, fleeing from the dead, inert thing that is the totality of my past actions. Although my acts are free, I am not free not to act; thus existence is characterised also by exigency.’ (Burnham, D. Papandreopoulos, G.) This is a basic format of what existentialism actually entails without further detail and/or reading. Within this study, I seek to create an in-depth map of what existentialism is, where it came from and where it is in our own day. The point of which is to see whether we today are really as existentialist as our own existential crises may suggest.

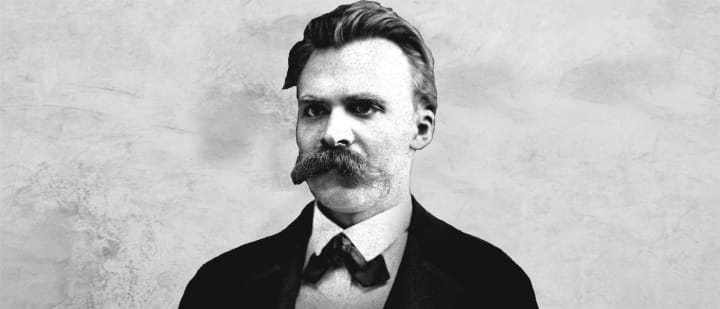

Existentialism is a philosophy that developed in the 19th century with two people who were considered to be spearheads of the movement: Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche. Neither of them actually used the term ‘existentialism’ but both are accredited with coming up with the absolute ideas which led to the entire movement later on. As existentialism changed and morphed over time, what we have now is unlike the existentialism talked about by these 19th century philosophers and so it is unclear as to whether they themselves would have supported it or not. Both Kierkegaard and Nietzsche focused on subjectives of human experience, how people dealt with the meaningless of life and how diversion was used to escape boredom. Kierkegaard’s own disdain for observatory subjects like mathematics and science and his preference for emotional ideas such as the meaningless of life and existence were showcased in some of his best works with one of his quotations from his book ‘Either/Or’ stating: “Life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.” (Kierkegaard, 1992). The main focus therefore of existentialism was primarily emotional states and how they impacted the ‘being’ part of human nature. Then came another layer, the feeling of meaninglessness - a sort of listlessness in which the person dwells on the idea that life is well and truly meaningless. This is similar to the common ‘existential crisis’ that we all have in our lives from time to time, but these is not the only things that existentialism is about.

Fyodor Dostoevsky is also a key figure in the history and development of existentialism but he is not only just important, he seems to shift the very meaning of existentialism into a different realm. It moves away from simply feeling that life is meaningless, but instead it moves towards the very idea of consciousness being a problem, an issue or a hinderance upon the mind. Consciousness seems to be not enough to solve anything and too much in terms of eliciting unwanted emotions and thoughts. Though it is important not to get the character of the ‘malcontent’ confused with the existentialist, they can be thought to be similar and both can be viewed in Dostoevsky’s text ‘Notes from Underground’ where the main character displays serious dissatisfactions within his soul for who he is and the life he has created for himself. He questions whether any of it means anything at all whilst also trying to actively change the very essence of who he is: ‘It is clear to me now that, owing to my unbounded vanity and to the high standard I set for myself, I often looked at myself with furious discontent, which verged on loathing, and so I inwardly attributed the same feeling to everyone.’ (Dostoevsky, 2009). Another one of Dostoevsky’s novels that creates what we understand today as the ‘existential crisis’ is his final famed work ‘The Brothers Karamazov’. Within this, Ivan Karamazov is said to have an existential crisis just over halfway through the novel in which he questions his entire life and the way he has lead it. This question is caused of Smerdyakov implicating Ivan in having a hand in his own father’s death and yet, there is no confirmation of a crime, just a confirmation of a context. Ivan though, takes this incredibly seriously and he states: ‘I am a sort of phantom in life who has lost all beginning and end, and who has even forgotten his own name.’ (Dostoevsky, 2010).

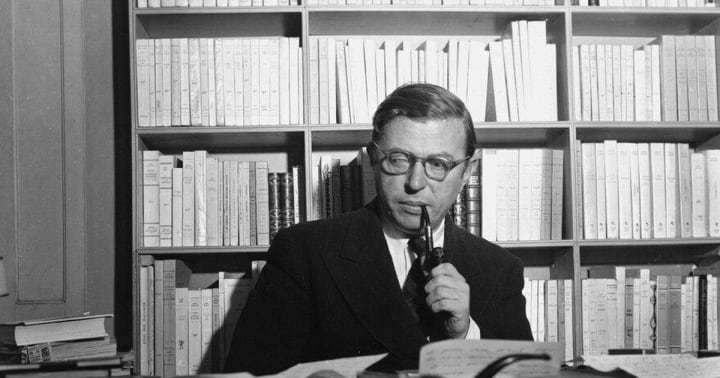

Existentialism moves once again during the 20th century with contributions and changes to the order made by Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre’s beliefs included that an individual should be responsible for all their rights, that total freedom came with total responsibility. He also believed that man was never truly free until this happened - which is practically never in the modern world. He argued that free human beings needed to be responsible for each and every part of their own being if they wanted to be and stay in a state of freedom. His three main themes were: radical freedom, choice and finally, responsibility. His argument that there is no fixed morality to determine human action but there is the responsibility to take charge of that action as an individual no matter what moral ideas are attached to it socially. This was Sartre’s exploration into what it meant ontologically of what it was to be human. In his book ‘Existentialism is Humanism’, Jean-Paul Sartre puts forward these claims regarding human dignity. Even though it is an outline for an incomplete project by Sartre, it is fair to say we learn quite a bit about his relations between human freedom and existential philosophy in this text, more so than any other text he wrote other than ‘Being and Nothingness’. In his book ‘Existentialism is Humanism’, Sartre discusses the term ‘ethics’ and what it means in terms of true freedom, a representation of what humans strive for but many do not really have. He states that existentialism can lead one to quietism - the belief that you should do nothing because you can change nothing. Sartre states that this quietist philosophy was only ever a part of existentialism in order for the upper class to maintain the status quo because, unlike the theories first put forward by Nietzsche and Kierkegaard, quietist existentialism promotes inaction whilst the two 19th century philosophers state that action is the only way to define being. He then seeks to debase humanity through the emphasis of the individual (Sartre, 1948). His theory proposes that you are the centre of your own existence in a somewhat narcissistic light and that this is because you can only ever see the world from your own point of view - you should not therefore, rely on others to give you the meaning to your own life. Instead of quietism, Sartre’s philosophies turn more towards the solipsistic side in the view that everyone is alone and the world is alone existing from their viewpoint. But Sartre then in ‘Existentialism and Humanism’ tries to ‘overturn the perception that existentialism is pessimistic and humanism optimistic.’ (Sartre, 1948).

Today, existentialism is seen in many different philosophies and is not simply prescribed to its own subsection of the study. Various philosophers from other parts of philosophy have included the existential in their own theories such as: Judith Butler in their groundbreaking book ‘Gender Studies as do critiques of race theory, psychopathology and even theorists of artificial intelligence. (Cromwell, 2020). Throughout the course of the late 20th and early 21st century, existentialism has shown it is more comfortable in the past as the simple ideas of action and being put forward by Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, but has evolved completely since the original ideas. This is foremost the analysis of interiority and language in gender theory put forward by Judith Butler and their critique of gendered behaviour and performance that is inspired by Nietzsche and his ‘Will to Power’. (Schrifft, A.D). This is even better solidified by the writings of Judith Butler out of their context of their book ‘Gender Trouble’ in which she speaks of the ‘becoming’ and ‘individuality’ of the theories of Simone de Beauvoir. They state, ‘the term 'female' designates a fixed and self-identical set of natural corporeal fact’ (Butler, 1998) - which means that according to Butler, Beauvoir’s theories focus on the self-identical actions of the female and so, this links back to the ‘doing’ and ‘action’ that was theorised in existentialism by Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. But then, they link it into the Sartrian philosophies of existentialism in which gender is a part of the existential body by being a ‘style’ and a ‘project’ that one works on that is not necessarily focal on the negative to be deconstructed, rather a construction of the self. (Butler, 1998). But they also argue that there are no system in which to construct these genders, instead it is entirely dependent on the person experiencing it - this is similar to how Sartre argues the body in his book ‘Being and Nothingness’.

Within the world of existentialism then, there are certain books that are better than others in order to understand the theories that lie within the existential bubble. Here is some literature to read so we can better understand this large culture and theory:

- Either/Or by Søren Kierkegaard

- Fear and Trembling by Søren Kierkegaard

- The Sickness Unto Death by Søren Kierkegaard

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche

- Beyond Good and Evil by Friedrich Nietzsche

- On the Genealogy of Morals by Friedrich Nietzsche

- Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche

- Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre

- Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Sartre

- Existentialism and Humanism by Jean-Paul Sartre

- The Words by Jean-Paul Sartre

- The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus

- The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky

- The Second Sex by Simone De Beauvoir

In conclusion, existentialism is ever changing. Through the lens of the books of Albert Camus, it shifts into absurdism in which life is meaningless in a positive light, a newer and slightly more exact symptom of post-war France. But one thing is true entirely, it is dependent on historical and social context of the people who believe in it. In Sartre and Camus’ own times, there was much requirement for positivity in the post-war context, the idea that many had died in war somewhat meaninglessly must be theorised to be an idea that is academic - therefore, absurdism is taken from it. We may continue to let existentialism evolve but if one thing is true it is that existentialism is not what we really think it is and what we believe existentialism is may actually be nihilism. Something more on par with intense levels of philosophical depression.

Citations List:

About the Creator

Annie Kapur

200K+ Reads on Vocal.

English Lecturer

🎓Literature & Writing (B.A)

🎓Film & Writing (M.A)

🎓Secondary English Education (PgDipEd) (QTS)

📍Birmingham, UK

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.