The reason we divide up our days into two sets of twelve.

And why we divide up hours and minutes by sixty.

As a great philosopher of our time put it, “Time is a valuable thing, Watch it fly by as the pendulum swings, Watch it count down to the end of the day, The clock ticks life away.” But why is time counted the way it is--the day first divided by two (AM and PM) then twelve (hours) then sixty (minutes) and then sixty again (seconds). It’s all so needlessly complicated. Why don’t we have a nice metric style system where everything is divisible by ten? To understand how we came to our current system of timekeeping we need to first ask this question:

How does a sundial work at night?

The answer is that it doesn’t. Before mechanical clocks you only tracked hours while there was daylight. A day started with sunrise, would have 12 hours and then ended at sundown. The length of an hour would depend on where you were in the world and when it was in the year--the hours would be longer in summer and shorter in winter.

Now sure, Wikipedia says that ancient Egyptians were keeping track of time at night by the stars. That was really just for time nerds though. Your average pyramid construction worker wasn’t tracking time at night because most of that time they were, you know, sleeping.

For most of human history keeping track of time at night, or really at all, wasn’t that important. People generally worked for themselves. We’re so used to being paid by the hour that we forget how artificial it is.

When mechanical clocks were invented in the fourteenth century is when you start to get the time system we recognize today. The clock still resembles a sundial--the clockwise motion of the hands of a clock mimic the movement of a shadow on a sundial. Note that this only holds true in the Northern Hemisphere, in the Southern Hemisphere the shadow goes the other way. We also kept the 12 hours that were on the sundial, but that’s not enough since we’re keeping track of day and night now. So we divide the day into Ante meridiem, Latin for before noon & Post meridiem, meaning after noon.

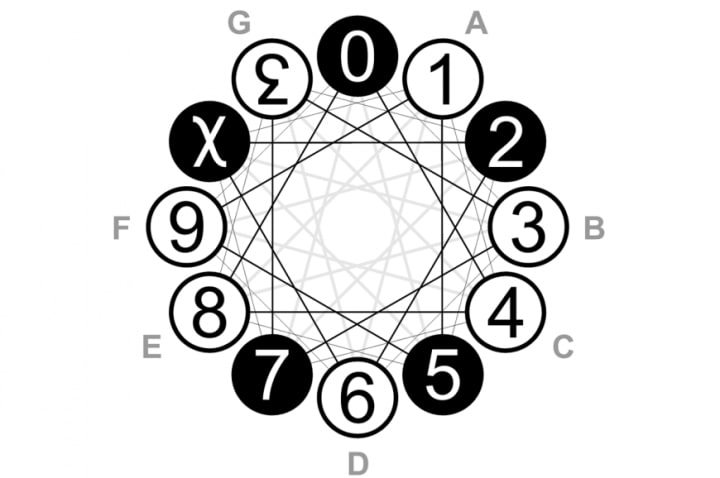

But, still, why 12 hours? The answer is that it comes from the Egyptians who had a Duodecimal system of numbering which has a base of 12 instead of our usual base of 10. A base 10 numbering system is something we’re so used to that the possibility of other numbering systems don’t even occur to us, but they are out there.

We can see vestiges of duodecimal systems around us. Twelve is one of the few numbers to have a second name - a dozen. 12 times 12 also has a second name, a gross. There are twelve months in a year. There are 12 signs of the Zodiac whether you go by western or Chinese systems. Twelve repeatedly shows up as an important number in multiple religions. Using a base of 12 has advantages--10 can only be divided by 2 and 5; 12 can be divided by 2, 3, 4, and 6. When you don’t have calculators being able to divide and get a whole number is important.

Then what about an hour and minutes being divided by 60? We can trace that back to the Babylonians who had a Sexagesimal numbering system which has a base of 60.

It turns out that there is a fairly natural way to count to 60 on your fingers (see the video). The way we measure angles, 360 degree in a circle, is also a remnant of a Sexagesimal system.

There was an effort to move to a metric style system of timekeeping where a day would be divided into 1000 “beats” which was proposed in 1998 by the clock company Swatch. Of course humanity said, no, we want to keep our system cobbled together from multiple ancient societies that used numbers completely different from our own and based on a device made out of stone, thank you very much.

About the Creator

Buck Hardcastle

Viscount of Hyrkania and private cartographer to the house of Beifong.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.