Operation Chromite: MacArthur's Stroke of Genius

Do the impossible and turn the tide of a war

Operation Chromite was a pivotal military operation during the Korean War that took place in the late summer of 1950. The operation was led by United States forces and aimed to turn the tide of the war in favor of the United Nations forces by landing a large number of troops at Inchon, a port city on the west coast of Korea.

Background and Context

The Korean War was a conflict that began on June 25, 1950, when North Korean forces, backed by the Soviet Union and China, invaded South Korea. The United States and its allies in the United Nations Security Council intervened on behalf of South Korea, and a protracted war ensued that lasted until July 1953. The Korean War was fought against the backdrop of the Cold War, a global struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union for influence and control.

The war began with the North Korean army rapidly advancing southward, pushing back the ill-prepared South Korean army and capturing the capital, Seoul, within three days. The United States responded by sending in troops and other resources, establishing the United Nations Command (UNC) under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur who had built his reputation in the Pacific during WWII. The UNC’s primary mission was to defend South Korea and restore its sovereignty.

By late July 1950, the North Korean army had reduced the ground held by U.N. troops to the southeast corner of the peninsula behind the Naktong River. During August and early September, American Soldiers and Marines and South Korean troops under the direction of General Walton Walker's U.S. Eighth Army fought savage battles to retain that toehold, the "Pusan Perimeter."

General Douglas MacArthur conceived a plan to break the stalemate. There were in fact several planning options, but the one selected was finally named Operation Chromite.

Planning

General MacArthur, the commander of the UNC, recognised that a direct attack on the North Korean army along the front lines was unlikely to succeed. Instead, he proposed a bold plan to land a large force behind enemy lines at Inchon, a port city on the west coast of Korea and close to the capital, Seoul, which would cut off the North Korean army’s supply lines and disrupt its command and control. The operation was one of the most audacious amphibious assaults in history, and it required precise planning and execution.

The planning for Operation Chromite began in late July 1950, and it involved a complex web of logistics, intelligence gathering, and deception. MacArthur’s staff spent weeks poring over maps and aerial photographs to identify potential landing sites and potential obstacles, such as sandbars and underwater mines. They also coordinated with the Navy to secure the necessary ships and landing craft, and with the Air Force to provide air cover for the operation.

Meanwhile, the UNC’s intelligence operations were working to deceive the North Koreans about the actual location and timing of the attack. They spread rumors that the attack would take place further south, near Pusan, which was the UNC’s main supply port. They also used double agents to plant false information about the UNC’s troop movements and intentions.

Challenges

The challenges were considerable, both political as well as military. Operational secrecy was also a key challenge.

Political

While MacArthur was determined to execute the Inchon operation from early July 1950, he faced considerable opposition and dissent in Washington and from among his own staff and commanders in Tokyo and Korea. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were sceptical about the operation’s viability, partly over the choice of Inchon and the short timetable, but mostly due to the operation’s voracious appetite for scarce resources and forces.

He faced down his own officers and a delegation from the US President, utterly convinced (at least to them) that the plan would work. He got the support he needed.

Military

The US forces in theatre had a large proportion of draftees, were undermanned and ill-equipped. There were major issues is assembling a suitable marine force with adequate equipment and materiel.

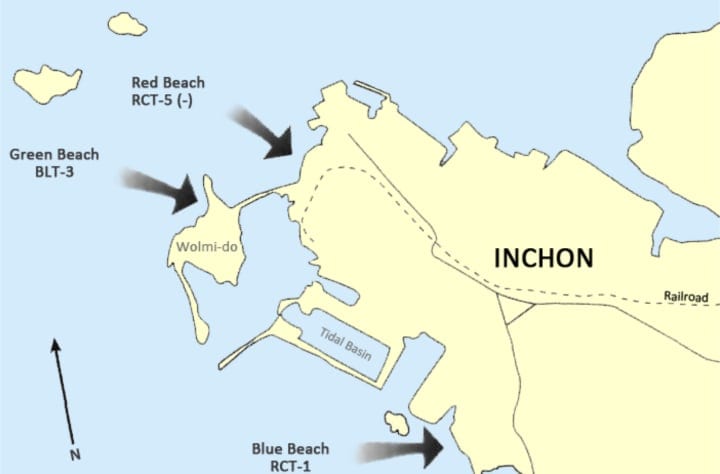

In the planning stages of Operation Chromite, one of the key challenges faced by the United Nations Command (UNC) was to identify a suitable landing site for the amphibious assault on the Korean peninsula. After considering several options, including the port of Wonsan on the east coast of North Korea, MacArthur decided to launch the attack at the port of Inchon, located on the west coast.

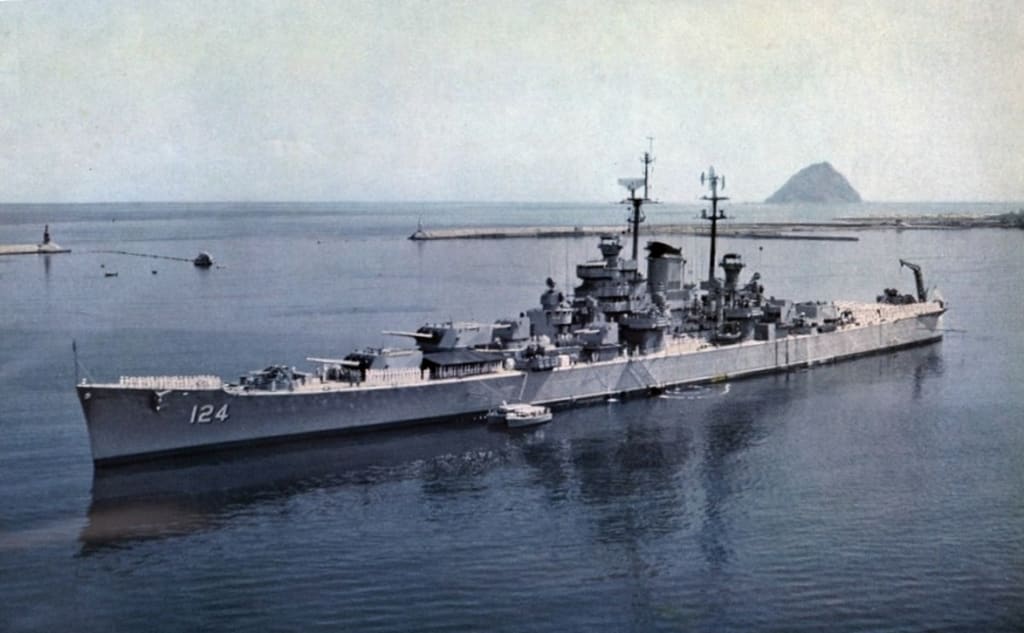

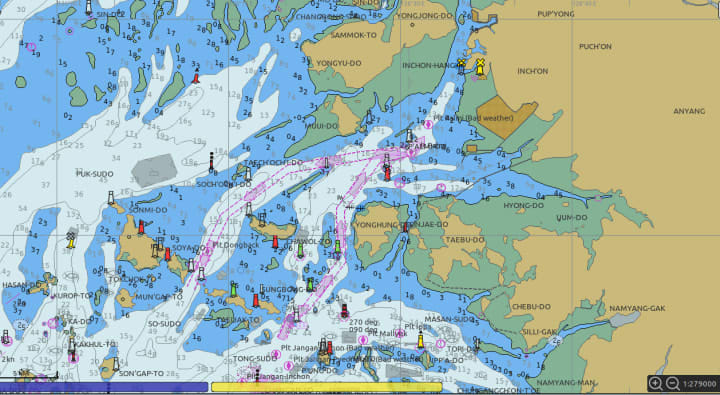

One of the critical factors in the success of the Inchon landing was the ability of the UNC to accurately survey the approach channel to the port. The approach channel was a narrow and shallow waterway that led from the Yellow Sea to the port of Inchon, and it was mined by the North Koreans.

On 1 September, Lieutenant Eugene F. Clark, USN, arrived in the Tokchok Islands aboard destroyer HMS Charity and in conjunction with ROKN personnel already there quickly set up a highly effective intelligence gathering network that obtained extensive intelligence on Inchon defenses and hydrographic features, while also conducting raids and engaging in several sampan-to-sampan gun battles with North Korean forces. Lieutenant Clark carried a grenade with him to kill himself in the event of imminent capture. He was awarded a Silver Star for his actions from 1-15 September, which included a personal reconnaissance of Wolmi-Do (not specifically mentioned in the award citation) and a Navy Cross for actions on 13-14 September, including turning on the navigation beacon on Palmi Do to assist U.S. destroyers and cruisers though the narrow channel to Inchon. - history.navy.mil

The surveying process was a slow and meticulous one. During the periods of low tide, Clark's team located and removed some North Korean naval mines, but, critically to the future success of the invasion, Clark reported that the North Koreans had not in fact systematically mined the channels.

In preparation for the amphibious assault, the UNC laid a total of 375 navigation marks along the approach channel to Inchon. These marks were carefully positioned to guide the landing craft through the heavily mined waters and into the safety of the harbor.

The use of ships to survey the approach channel was a critical component of the planning and execution of Operation Chromite. By accurately identifying the location and extent of the mines, the UNC was able to clear a safe path for the landing craft to reach the shore.

And once the channel had been navigated, there was another challenge.

Inchon's harbor is surrounded by extensive mud flats. These mud flats are exposed at low tide, creating a wide expanse of soft, muddy terrain that is difficult to traverse on foot or by vehicle. During the planning of Operation Chromite, the mud flats presented a significant challenge for the UNC, as they would have to be crossed by the landing craft in order to reach the safety of the harbor.

And the initial naval bombardment force comprising US and British ships would have only 2 hours before being stranded as the tide went out.

On 13 September, in broad daylight, because there was no choice, the bombardment force would have to come up the narrow channel single file with the flood tide and anchor less than half a mile off Wolmi Do with head toward the sea, and would have about two hours to shell the island before getting stranded in the mud by the ebb tide.- history.navy.mil (ibid.)

Timing of the tide was essential so that the landing craft could pass over the mud flats at high water. The Navy carried out tidal surveys to be sure that the timings were right for the amphibious assault.

The tides at Inchon have an average range of 8.8 m and a maximum observed range of 11 m, making the tidal range there one of the largest in the world and the maximum in all of Asia. The Navy divers observed the tides at Inchon for two weeks and discovered that American tidal charts were inaccurate, but that Japanese charts were quite good.

Operational secrecy and surprise

Keeping this vast plan a secret was another major challenge, and the key to it was misdirection.

In order to ensure surprise during the landings, UNC forces staged an elaborate deception operation to draw North Korean attention away from Inchon by making it appear that the landing would take place 105 miles to the south at Kunsan. On 5 September 1950, aircraft of the USAF's Far East Air Forces began attacks on roads and bridges to isolate Kunsan, typical of the kind of raids expected prior to an invasion there. A naval bombardment of Kunsan followed on 6 September, and on 11 September USAF B-29 Superfortress bombers joined the aerial campaign, bombing military installations in the area.

In addition to aerial and naval bombardment, UNC forces took other measures to focus North Korean attention on Kunsan. On the docks at Pusan, USMC officers briefed their men on an upcoming landing at Kunsan within earshot of many Koreans, and on the night of 12–13 September 1950 the British Royal Navy frigate HMS Whitesand Bay landed US Army special operations troops and Royal Marine Commandos on the docks at Kunsan, making sure that North Korean forces noticed their visit. (Wikipedia)

Execution

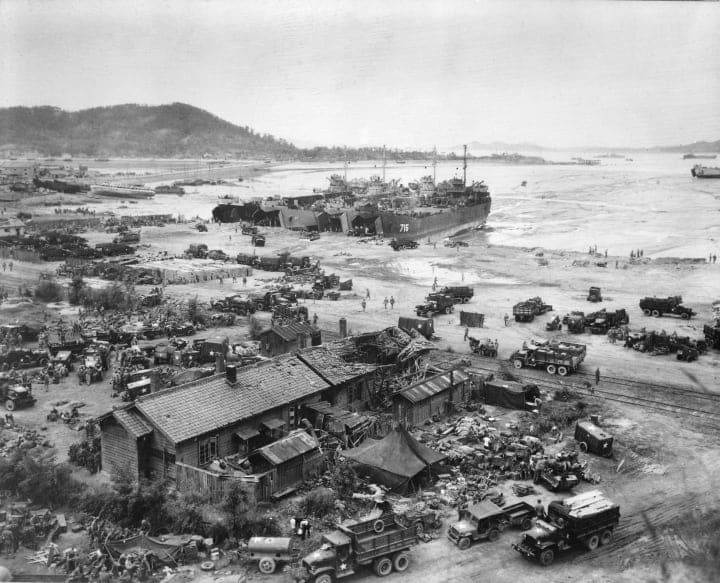

On September 15, 1950, the UNC launched Operation Chromite. The operation involved a massive amphibious assault, with 261 ships and landing craft carrying over 70,000 troops. The landing itself was carried out with surgical precision, with the first wave of troops hitting the beach within minutes of each other.

The North Koreans were caught almost completely off guard, and the UNC was able to establish a beachhead and secure Inchon within a matter of days.

Impact

General Douglas MacArthur had many faults and was accused of 'going native', spending many years in the Far East and rarely visiting the US. He was an outstanding military strategist whose eyes were sometimes clouded by his dreams of his place in history, but Inchon is one of his greatest military achievements.

Operation Chromite was a major turning point in the Korean War. It not only disrupted the North Korean army’s supply lines and command and control, but it also boosted the morale of the UNC and its South Korean allies. The successful operation also helped to restore the confidence of the American public in their military and its ability to win the war. In addition, it marked a significant victory for General MacArthur, who had faced criticism for his handling of the early stages of the war.

Following the success of Operation Chromite, the UNC pursued a strategy of pushing northward, with the ultimate goal of reuniting the Korean peninsula under a democratic government. However, the North Koreans and their Chinese allies were not willing to give up without a fight, and the war continued for another two and a half years, with heavy casualties on both sides.

Despite the ultimate stalemate of the war, Operation Chromite remains a significant moment in military history. The operation demonstrated the importance of bold and decisive leadership, careful planning and execution, and the use of deception and intelligence in warfare.

It also highlighted the importance of sea power in amphibious assaults, and set the stage for similar operations in future conflicts, such as the Vietnam War. That later war was not a stalemate and unlike Inchon and Koreas is still an embarrassment to the USA.

The operation resulted in significant civilian casualties, and it led to a backlash from the North Koreans and their allies, who launched a counteroffensive that inflicted heavy losses on the UNC, bringing China into the war on 19 October 1950 when 200,000 of their troops crossed the North-South border. MacArthur had grossly underestimated the strength of Chinese forces - or deliberately ignored the intelligence for other reasons, such as a wish to recover the entire Korean peninsula.

In addition, some historians have criticised the operation as overly risky, and have argued that the UNC could have achieved its objectives through less risky means, such as a direct assault on the front lines.

Perhaps so, but we will never know.

Conclusion

Operation Chromite was a pivotal moment in the Korean War, and it remains a significant moment in military history.

However, it is important to recognise the drawbacks and controversies of the operation, and to understand the broader context of the Korean War. The war was fought against the backdrop of the Cold War, and it had significant geopolitical implications for the United States and its allies, as well as for the Korean peninsula itself. Stalin assisted China with armour and airplanes, but was wary of entering the war directly.

Ultimately, the war ended in a stalemate, with the two sides agreeing to a ceasefire in 1953 that left the peninsula divided along the 38th parallel.

Chromite was a bold and daring operation that helped to turn the tide of the Korean War, and it remains a significant moment in military history. However, it is important to remember that the war itself had complex geopolitical implications and human costs, and that its legacy continues to shape the region today and resulted in the establishment of another nuclear power.

Sources

• Halberstam, David. The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. New York: Hyperion, 2007.

• Millett, Allan R. The War for Korea, 1945-1950: A House Burning. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 2005.

• Stueck, William Whitney. The Korean War: An International History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995.

• Toland, John. In Mortal Combat: Korea, 1950-1953. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1991.

• Weintraub, Stanley. MacArthur's War: Korea and the Undoing of an American Hero. New York: Free Press, 2000.

• Hoyt, Edwin P. The Inchon Landing: An Eyewitness Account. New York: Praeger, 1998.

• Hastings, Max. The Korean War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

• Blair, Clay. The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-1953. New York: Times Books, 1987.

• Fehrenbach, T. R. This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness. New York: Macmillan, 1963.

• Ridgway, Matthew B. The Korean War. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1967.

• Webb, James The Emeperor's General, Broadway Books, New York, 1999. (faction)

• Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Inchon

About the Creator

James Marinero

I live on a boat and write as I sail slowly around the world. Follow me for a varied story diet: true stories, humor, tech, AI, travel, geopolitics and more. I also write techno thrillers, with six to my name. More of my stories on Medium

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.