Of Libraries and Bad-Ass Librarians

Why old-fashioned libraries — and the bad-ass librarians who look after them — matter.

True story.

In the Sahara Desert in the mid 2000s, following the global chaos of the 9/11 terror attacks and in the wake of al-Qaeda and Isis insurgencies across much of the Sahel, the semi-arid African region that borders the southern edge of the world’s largest, most expansive desert, a small band of self-taught antiquarians and librarians vowed to hide priceless ancient Arabic texts written on parchment and bound in books, some dating back to the 15th century and earlier.

They knew that if these texts — hundreds of thousands of them — fell into the hands of Islamist insurgents, they would be burned and scattered to the desert winds, lost to history forever.

Years earlier, Abdel Kader Haidara, an adventurer and collector for Mali’s national library, scoured the Sahara Desert and trekked along the Niger River from the desert town of Timbuktu, once the site of a long-forgotten empire that ruled over West Africa much as the Ancient Egyptians had ruled over Egypt and North Africa, and the Ancient Romans ruled over much of what we know today as continental Europe.

Haidara salvaged tens of thousands of Islamic and secular texts, many of which were crumbling to dust inside heavy trunks in desert encampments throughout the central Sahara.

With violent Islamist insurgencies threatening to spiral out of control — Timbuktu itself would be overrun, much as the ancient city of Palmyra in Iraq was overrun by the ISIS-offshoot Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) during the still ongoing civil war in Syria — Haidara and his band of merry men, and women, managed to smuggle 350,000 volumes of ancient texts and spirit them to safety in southern Mali.

Haidara’s exploits became the subject of the 2016 book by veteran foreign correspondent and one-time Newsweek bureau chief Joshua Hammer, titled appropriately, The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, officially known by its more long-winded, prosaic title, The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu and Their Race to Save the World’s Most Precious Manuscripts.

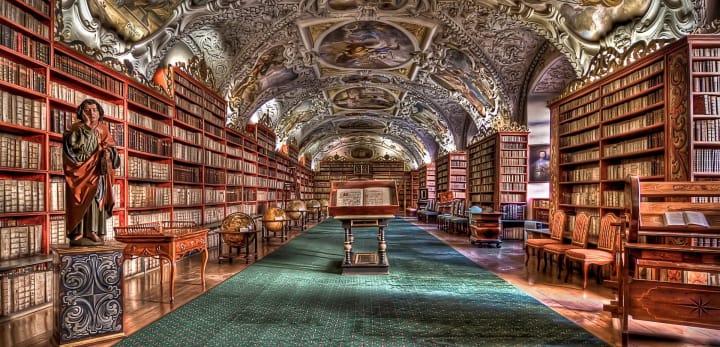

Far from being a remote backwater — pun intended — in its day Timbuktu was a thriving, centuries-old center of international trade and knowledge, akin to the Great Library of Alexandria, arguably the largest and most significant library in human history, burned to the ground by Julius Caesar in 48 BC, with the loss of an incalculable number of texts from Ancient Greece and Egypt, and possibly even Rome itself. The Library of Alexandria was home to some 400,000 texts, it’s been said, which puts Timbuktu’s 350,000 texts in a sobering perspective.

(Despite the many problems facing our modern world, Alexandria is once again the site of a world-renowned library, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, officially inaugurated in 2010. This time priceless books are stored on digital files, but that doesn’t mean books themselves are passé: The library has shelf space for 8 million books; the main reading room covers some 220,000 square feet, or 20,000 square meters. That’s some serious space.)

It’s worth noting that as scientists, scholars, engineers, ethicists, poets and philosophers made the pilgrimage to Timbuktu to share ideas and debate the meaning of life, Europe was mired in the Dark Ages. By the 16th century, a quarter of Timbuktu’s population of 100,000 were students: You might say that Timbuktu, geographically anchored in the middle of the Sahara Desert, was the original college town.

With its reputation as a center of learning, it was not long though before Timbuktu found itself being pulled between two opposed Islamic ideologies, “One open and tolerant,” Hammer writes in Bad-Ass Librarians, “the other inflexible and violent.”

Enter the 21st-century jihadis, in the form of an al-Qaeda offshoot calling itself Al Qaeda in the Islamic Magreb (AQIM). The jihadis overran Timbuktu in 2012. You don’t need to know about the terror and havoc they wreaked on the desert town’s residents; you’ve heard it all before. Music was banned, women were forced to wear veils, men were compelled to grow beards, and the bad-ass librarians sprang into action.

Under cover of darkness and pretending to be compliant with their jihadi occupiers and the jihadis’ strict idea of Sharia law, the bad-ass librarians secretly packed tens of thousands of manuscripts into metal trunks, loaded them onto mule carts, and smuggled them to Mali’s capital of Bamako, at risk of re-education camps, public amputations — or worse.

Not every manuscript was saved: In January, 2013, according to Hammer’s research, gleaned largely from eyewitness accounts, some 4,000 manuscripts perished in a bonfire outside one of Timbuktu’s most fabled institutes of learning.

It all makes for one hell of a story.

In the end, France intervened — forcefully and with all the might of a 21st-century Western power. France is still there, serving more as an informal international peacekeeper in Mali and regional states like Niger, Chad and Cameroon, this time against a new and equally violent Islamist insurgency group called Boko Haram.

Boko Haram are not too keen on books, either — or education, for that matter, or any form of learning aside from their own extremist interpretation of the Koran.

And there the story lies.

•

The bigger question.

The bigger question, and the big-picture issue that speaks to all of is, is why libraries matter.

Why would a mild-mannered, middle-aged scholar with a wife and many children risk his life, and the lives of many others who worked for him and with him, to save some silly books?

Ah, but there — as the brilliant post-modern poet-philosopher and writer Neil Gaiman writes in his incisive, insightful, witty and wise nonfiction anthology The View from the Cheap Seats — you’ll find the very stuff of life.

Books are us.

They are humanity itself.

And libraries are where you’ll find them.

I am a writer, but I am also a reader, and my reading began early.

In the middle years of my childhood I was lucky enough to live within a single bus ride of a children’s library that was open during the summer holidays — and only the summer holidays, on the presumption that in the fall and winter, children were in school, and schools presumably had libraries. My tastes were forged early, and a kindly librarian was often on hand to point me in the right direction.

A literate society is an informed society, and an informed society is good for democracy. Informed voters make good decisions, and informed decision makers are good for public policy.

Good fiction and good non-fiction have a similar effect on the reader, but they are different. Good non-fiction informs and educates; good fiction speaks to our imagination and inspires creative thinking — and creativity. Good non-fiction tells us what’s happening, now, and why. Good fiction drives us forward. We have to turn the page, to find out what happens next.

In his essay on why fiction matters, Gaiman makes an interesting point: We relate to the characters in a novel. By placing ourselves in their shoes, we learn empathy. That’s a good lesson for anyone to learn, but especially children.

We step into the character’s shoes; we feel their hopes and dreams, and we feel their pain when things go wrong. Gaiman argues that this is especially true of the written word, as opposed to watching a film or TV on a screen, because our imagination is forced to fill in the blanks — what a character looks like, how they speak, why they think and act the way they do, how they process thought and emotion, their outlook on the world.

A good novel changes us. The best novels change us without our realizing it. A popular becomes part of the shared cultural experience, but it’s also something very personal. No two people read a work of fiction the same way.

Perhaps that is why the great novels are timeless. They do not date or age, because every single person reading them for the first time will see different layers, different meanings.

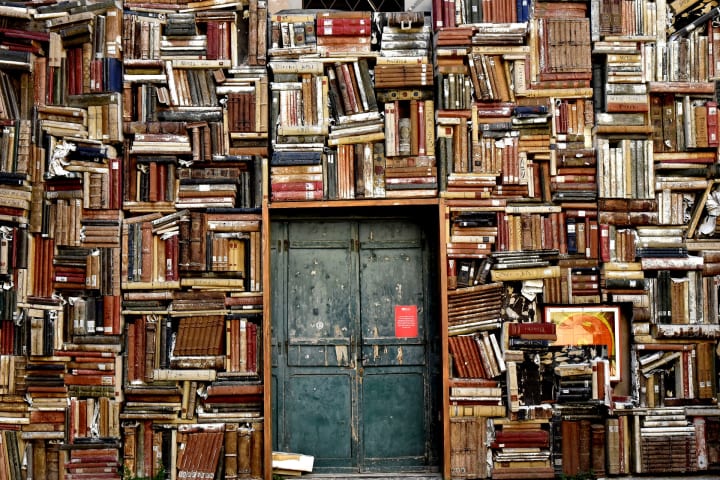

Books are physical. They have heft. You touch and feel a book, and that is not an experience you can get from a screen. Those bad-ass librarians in Timbuktu understood that, just as they understood that a library was important — a physical place where people can gather and read physical books and communicate and exchange ideas in person. We don’t have to accept the world as it is. We, the people, have the power to effect change, and change can be for the good.

That is why oppressive regimes, failed states and rogue nations burn books. Books are ideas, and ideas are dangerous to those who are determined to rule through absolute power. That is why Stephen King and Salman Rushdie and Jonathan Franzen share so much in common, even though they are very different writers with very different points of view.

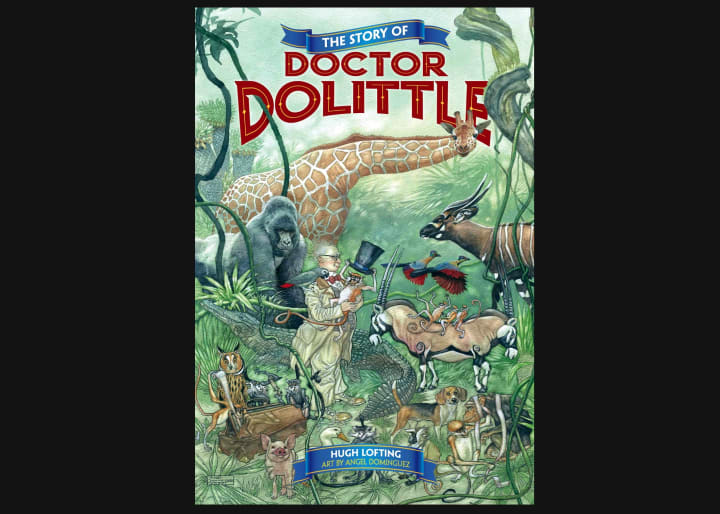

My own childhood reading ranged from Hugh Lofting to Joy Adamson to Ray Bradbury, and even though I lived my entire childhood in tiny, cramped apartments in the middle of big cities, the family constantly moving between one city and another, that early reading gave me a lifelong passion for the outdoors, for the wilderness, and a yearning to one day see the wilds of Africa.

I learned a valuable, lifelong lesson from those summer visits to the children's library in Montreal: that Hugh Lofting’s The Story of Doctor Dolittle, the book, was better in every way to Doctor Dolittle, the film. Books are often better than the films that are made from them.

The clue is in the name — the book’s full title was The Story of Doctor Dolittle: Being the History of His Peculiar Life and Astonishing Adventures in Foreign Parts Never Before Printed, and it’s impossible for an impressionable young mind to see that title on a book and not feel at least a twinge of youthful curiosity.

Doctor Dolittle is a childlike whimsy, but look beyond the cover and the words inside and there is a very adult, sobering story behind those Astonishing Adventures for children. Lofting wrote the book as letters to his children while serving in the trenches of the First World War.

His nerves shattered, surrounded by death and desperation, he wanted to show his children a world of light and joy and boundless possibility. By creating a fanciful world where animals could talk and a kindly doctor could talk to them in kind, Lofting staved off his own depression and fear of dying, arbitrarily and at any moment in a muddy trench in a meaningless war that meant nothing to anyone but a handful of entitled nobles. A young serviceman doing his duty in the trenches of World War I gave the world a timeless classic that is read to this day.

The Story of Doctor Dolittle was published in 1920, and it just recently marked its 100th anniversary.

And, yes, the book is still better than the film.

Those bad-ass librarians in the Sahara Desert knew something else — that escapism helps readers deal with an impossible situation, whether it’s a violent insurgency driven by religious extremists or lockdown in the middle of a pandemic, or simply recovering from a bad day at work.

Gaiman again: Escapist fiction is just that: fiction that opens a door, shows the sunlight outside, gives you a place to go where you are in control, are with people you want to be with, and more importantly . . . gives you knowledge about the world and your predicament — skills and knowledge and tools you can use to escape for real.

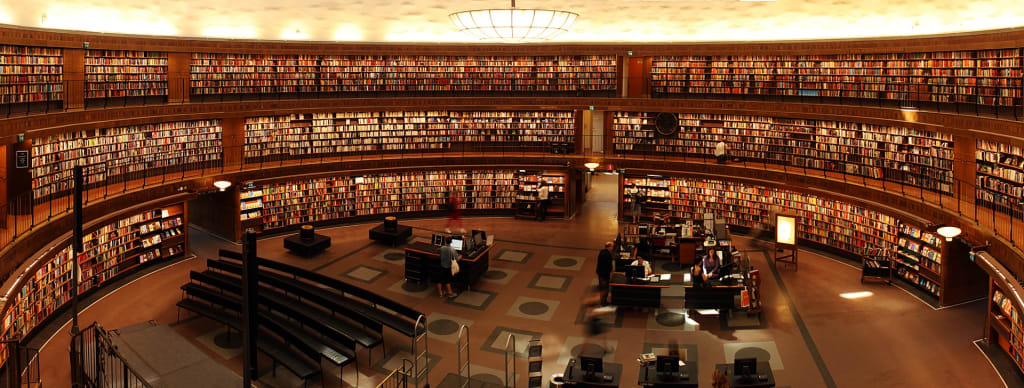

Libraries, whether they house collections of ancient text in the middle of the world’s largest, most impenetrable desert, or whether they’re home to children’s classics in the middle of a major metropolis, are about the freedom to dream, the freedom to learn new things and fall in love with new cultures and new places, and the freedom to think for oneself.

Books exist on paper and in the digital realm and on audio. There’s something about holding, touching, feeling and reading an actual, physical book, though, in the original hardcover, knowing that so many other visitors to the library have done the same.

It’s in a library, too, a library with actual, real, physical books, that you’re most likely to find a bad-ass librarian.

•

This year’s World Reading Day, also known as World Book and Copyright Day, is Friday, April 23.

There are some great Facebook groups for Vocal writers like the Vocal Creators Lounge if you want to be more active in the community.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/503959543406774

The Creators Lounge and others like it are good places to share and get feedback about your work, or find encouragement when you’re struggling with a piece.

About the Creator

Hamish Alexander

Earth community. Visual storyteller. Digital nomad. Natural history + current events. Raconteur. Cultural anthropology.

I hope that somewhere in here I will talk about a creator who will intrigue + inspire you.

Twitter: @HamishAlexande6

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.