Netflix's You and how 'nice guys' became the real villains

Now returning for a third series, the hit show is part of a wave of film and TV subverting preconceptions about the men who commit violence

cliché about villains propagated by film and TV is that they’re physically conspicuous, and so anyone with eyes can see they are a threat. That's why, from Freddy Kreuger in Nightmare on Elm Street to Rami Malek’s character Lyutsifer Safin in the new Bond film No Time To Die, villainy has been visually coded via the extremely prejudicial use of facial disfigurements.

But equally we know that bad people, whether predators or murderers or otherwise, are not immediately identifiable by either their looks or the way they present themselves – hence why, in real life, there are regularly stories of people guilty of the most heinous acts, in which neighbours, colleagues or acquaintances remark how ordinary they seemed, or what a "family man" they appeared to be. Supporting this uncomfortable truth has been a swell of recent stories on film and TV, which have been focused in particular on bad men, who are all the more dangerous for their ability to pass themselves off as "respectable" – to appear as the "nice guy". And just as some horror films may provide perverse comfort with their very obvious boogeymen, so these deceptively genial villains help us to confront faulty preconceptions about who appears to be a good and bad person – and what we deem to be good and bad behaviour. The trope of casting the "nice guy" as the villain is increasingly relevant, in particular, in a post-#MeToo world where the cultural discourse about male violence grapples with the fact that perpetrators are usually not mythical monsters or social outcasts, but everyday "respectable" men who trade on their status to abuse women.

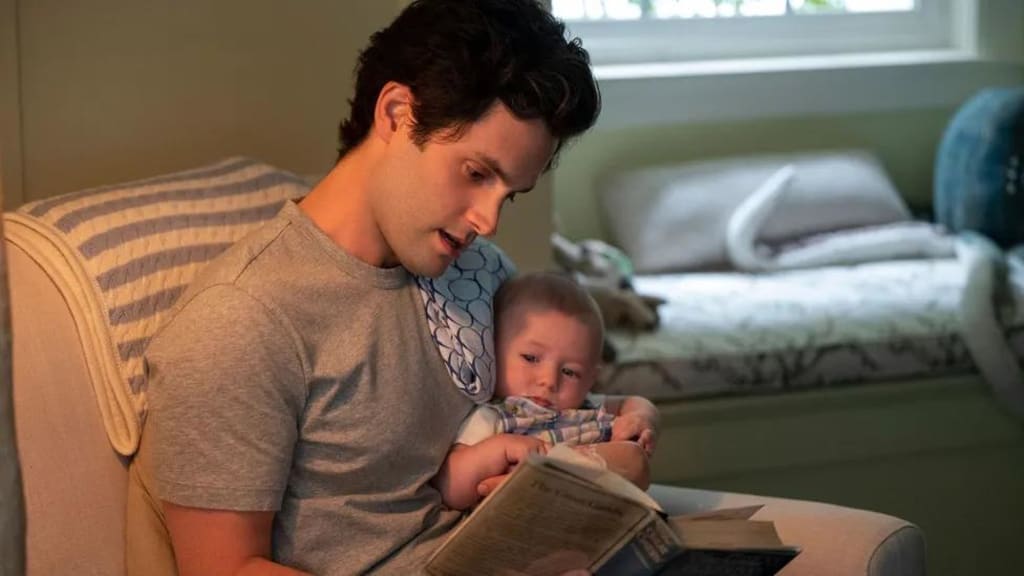

One show that has explored this trope within a mainstream, pop-culture context is Netflix's You, which returns for a third series today. In it, former Gossip Girl heartthrob Penn Badgley plays Joe Goldberg, a charming, handsome and diffident bookseller – with a secret sideline in stalking women and serial killing.

The series allows him to present himself through a narrative voice-over as a wry, humorous, clear-thinking anchor in a world of delusional materialists, who always has a morally righteous way of justifying his actions. Yet, beneath the surface of his smooth self-presentation, both to the other characters and the viewer, his villainy is extreme and undeniable: his method of gaining information on the women he supposedly has romantic feelings for is to stalk them, hack their communications, break into their homes and steal their things. If anyone gets in his way he is content to kidnap and kill them – even as his interior monologue woos the audience with his seductive point of view.

A cultural reckoning

Other recent works reckoning with toxic "nice guys'' include Emerald Fennell's Oscar-winning, zeitgeist-capturing film Promising Young Woman (2020), which gave us a slew of would-be date rapists who protest in so many words "But I'm a nice guy!" when the drunk woman who they took home to take advantage of, reveals herself as sober, avenging angel Cassie (Carey Mulligan). The crucial thing about these men is that they actually believe that they are nice guys. "You have [these] characters that genuinely believe they're innocent," says Dr Catherine Wheatley, a senior lecturer in film studies at Kings College London. "It's a problem of conflicting visions." Arguably, this only serves to make their villainy even more disconcerting.

These toxic "nice guy" narratives are exposing the kind of insidious paradigms of "acceptable" masculinity long implanted in our culture by film and TV

Elsewhere, the Irish thriller Rose Plays Julie (2019) by Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor, shows the charm that can smooth over great malignance with its story of a young woman Rose confronting her long-lost biological father Peter, a smooth celebrity archaeologist with a secret history of sexual offences. Meanwhile over on TV, Michaela Coel's incredible drama I May Destroy You showed violation of consent could be committed by the most innocuous seeming perpetrators: Zain (Karan Gill) who slyly removes his condom during sex with Arabella (Coel), is initially styled as the nice guy, a cosy alternative for Arabella to another night in alone with her PTSD from a previous assault.

Among other things, these toxic "nice guy" narratives are exposing the kind of insidious paradigms of "acceptable" masculinity long implanted in our culture by film and TV. What's clever about You's knowing screenplay is that it invites the audience to see how Joe's self-justifying sociopathy sits at the extreme end of a behavioural spectrum idealised by pop culture as romantic, masculine and heroic. In series one, Joe is obsessed with an ill-fated girl named Beck (Elizabeth Lail), and breaks into her apartment to hack her computer and read her messages. She returns unexpectedly, so he hides in her shower, as the voiceover asserts: "I'm not worried, I've seen enough romcoms to know that guys like me are always getting into jams like this."

Indeed films, and particularly romcoms, have long had a troubling tradition of valorising "nice guy" protagonists whose behaviour is in fact very toxic indeed, and framing boundary-transgressions as aspirational attempts to win the fair maiden. In Richard Curtis's About Time (2013), for example, Curtis presents a whimsical time-travel movie with a likeable lead in Domnhall Gleeson who nevertheless uses the ability to go back in time to repeatedly replay a sexual situation with his eventual wife Mary (Rachel McAdams) to his advantage. It's an action that, as critic Ryan Gilbey pointed out in the New Statesman, "would play in any other genre as date-rape. He just happens to use time-travel rather than Rohypnol."

Another Richard Curtis film: Love, Actually (2003) has similarly drawn a lot of flack over the years for the notorious scene in which Mark (Andrew Lincoln) shows up on the doorstep of his friend's wife, Juliet (Keira Knightley) with cue cards proclaiming his love. Despite this being out of the blue, with no precedent in their relationship for this kind of intrusion, she is charmed and hence the film validates this doorstepping and wraps it up in the bow of romanticism. Defending it last year, another actress in the film, Martine McCutcheon told Digital Spy, "I think people do crazy things when they're in love". But that's a justification that, while core to classic rom-com thinking, is very dangerous when applied to real life, love being used to justify many terrible actions. It could also have come straight from the mouth of You's "nice guy" villain Joe, as he commits another heinous crime in the name of pursuing the latest object of his affection.

Not-so-romantic leading men

This kind of romanticisation of noxious behaviour stretches back all the way through film history. There is a distinction to be made between tales like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and The Picture of Dorian Gray which deal in duality and moral extremes, and the more insidiously toxic behaviours of male characters who are exalted in films that intend them to be seen as impressive. Wheatley is an expert on what she calls "the taint of villainy" in screwball comedies and melodramas, and points out how, for example, the lolloping charm machine that was Cary Grant is in fact a deeply ambivalent on-screen presence. "Even when he's in the romantic leading man roles, he's a bully, and he's duplicitous, and he can be quite moralistic, and he leads these women into positions that they don't really want to be. That's something that is celebrated as a form of masculinity," she says, adding that the same applies to a more modern leading man like Harrison Ford, in his roles in the likes of the Indiana Jones films and Blade Runner (1982). Wheatley has been teaching Blade Runner to her students for years and talks about screening it before and after #MeToo. In the latter instance, she says, "I suddenly saw the film in a completely different light. You see actually how abusive he is in that role. There's the scene where he pushes Sean Young up against the wall and she says 'No, I don't want it' and he says, 'Yeah, yeah, baby you do'. I think that figure has a long history that goes from before Cary Grant to John Wayne of this masculine American hero that takes what he wants. And it's in the westerns, it's in the noirs. It's in Hitchcock."

In our culture there's this idea that anybody that's in a respectable job – especially any man – has a stronger claim to the objective truth – Catherine Wheatley

These figures are so instilled in our popular imagination as masculine ideals and so frequently played by devastatingly handsome movie stars, that it's a wrench to see them for what they truly are. Even when there is really no ambiguity: in You's case, it has been an apparent source of frustration to Badgely that, no matter what Joe does, fans of the show have still romanticised him and tweeted about wanting to be locked in his glass murder box. Though this is also, perhaps, a symptom of the show not being quite as subversive as it thinks it is.

Hannah J Davies is deputy TV editor at The Guardian, and says she has a love-hate relationship with the show – for while she enjoys it on the level of a slick, funny, addictive soap, but she thinks it is confused about what it stands for. "It doesn't really skewer anything. It takes you 80 percent of the way there and then doesn't go through with it. Everything's vocalised though [Joe] so it wants to have its cake and eat it. It wants to be like, 'This guy is an absolute monster' but also he gets to narrate it, and he's the one that gets to have the gag.

By contrast, Promising Young Woman and I May Destroy You do use their studies of skewed male self-perception to greater ends – by centring the female perspective, and showing how female victims' suffering can go unrecognised while not-so-"nice guys" are let off the hook. "The reason why I May Destroy You was substantially different [to You] was that we had those two different viewpoints already baked into it. We had Zain [and] we had Arabella, who was learning about consent and 'stealthing', along with the vast majority of the audience – who may not have known that exact term."

Meanwhile both Promising Young Woman and Rose Plays Julie foreground the element of social status in their explorations of gendered abuse to show how "respectability" can be weaponised by male characters who occupy exalted social positions. In the former, Ryan (Bo Burnham), Cassie's boyfriend, who it turns out was one of the men who stood and watched as her friend Nina was assaulted in college, is a paediatric doctor, and when the police come to question him it is with nauseating deference. Meanwhile in the latter, Peter is famous, while Rose is a quiet nobody. "[In our culture] there's [this idea] that anybody that's in a respectable job – especially any man – has a stronger claim to the objective truth," as Wheatley puts it.

While on a cosmetic level, You does wave in the general direction of the fact that Joe has been able to go about his criminal business undetected because he is a nice-looking white man, it has no real interest in delving into the human cost of this unmerited power excess. In the new series, the stakes have dramatically changed for Joe. Together with Love, his equally murderous, equally beautiful beau from series two, he has moved to a fictional Silicon Valley-esque suburb full of tech billionaires, anti-vaxxers and mommy bloggers. Now a father, he is trying – really trying – to keep his murderous impulses in check for the sake of his son. He is reckoning with his own traumatic childhood with the end-game of creating a better environment for his kid. When he falls for a female colleague at the library where he works, the tension arises from his attempts to hide this from Love, who has a habit of murdering rivals for Joe’s affection. This Mr and Mrs Smith school of gender equality makes for a bleakly amusing ongoing set-up.

The problem is that, now, in apparently encouraging the viewer to root for Joe to let the better angels of his nature triumph, the show seems to also require them to look past the body count he has amassed, and in pitting him against a female adversary in his wife – who is equivalently violent and charming – meaningful social commentary is eclipsed by a rarefied form of domestic farce. With series four just announced, it seems unlikely that Joe will get a comeuppance anytime soon. A show that hinges on a charismatic, good-looking monster is evidently loath to circumscribe its main draw, for Penn Badgley is a bona fide heartthrob with cheekbones that you could ski down. And, as the “nice guy” villain trope evolves, so too do audiences, who adopt a playful edginess in framing their attraction to an objectively foul man who would ruin their lives in a heartbeat. In that sense, perhaps the show makes its point more effectively than it realises about how men are let off the hook, as long as they look the part.

More generally, too, now culture is recognising the "nice guy" as a potential villain, where do we go from here? One thing's for sure: there is no level of subverting masculine tropes that can top the elevation of female points-of-view. There are moments when You flirts with switching allegiance but at the time of writing – unlike Joe – it doesn't have that killer instinct.

About the Creator

Mao Jiao Li

When you think, act like a wise man; but when you speak, act like a common man.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.