Neil Armstrong and the Rebirth of a Dream

A decade ago, when the first man to walk the Moon called for a new age of space exploration, it was inspiring but fanciful. That’s no longer the case.

WHAT DO YOU ask a man who walked on the Moon, and has never been able to live it down? All because he happened to be the first human being to set foot on another world?

This is the thought that had me brooding a decade ago this week, as I nursed a glass of red wine and peered across the vast hall of men and women in business attire who shuffled to and fro, anxious to enter the Parkside Ballroom at the Sydney Convention Centre in Darling Harbour, where Neil Armstrong was to make what would become — unbeknownst to us all — his last visit to Australia.

The 81-year-old space veteran had come to mark the 125th anniversary of Certified Practising Accountants of Australia, the professional accounting association. He has a soft spot for accountants: his father, Stephen, had worked all his life as a county auditor for the state government in Ohio.

Armstrong told the awestruck assembled crowd that, as a young man, he had an aptitude for mathematics, graduated in aeronautical engineering and became a test pilot (and eventually an astronaut). Both professions, he said, rely on maths: “In my case: calculus, differential equations and linear algebra. In your case, arithmetic … but mathematics nevertheless,” he quipped, to delighted laughter.

He was a surprisingly sprightly, lively and very engaging speaker. I say ‘surprisingly’ given his widespread reputation as a recluse, so I had expected a more halting performance. But he mesmerised the room — partly, no doubt, due to his exalted place in history — but also because he could really spin a tale, and carry you with him.

Speaking for more than an hour, the former commander of the history-making Apollo 11 mission recounted his long preparation for the mission, recalling the moment when his three-man crew hurtled free of Earth’s gravity at “more than 10 times the speed of a rifle bullet.”

“You see city lights on the African coast and notice lightning flashes illuminating thunderheads, like neon mushrooms far below you,” he said. “You can see Australia off to the right and Japan off to the left, and all of a sudden, you can see the entire circle — the whole planet Earth, kind of a gigantic blue medicine ball covered with white lacy clouds, and it’s floating slowly away from you into the inky black sky.”

They knew they were on a mission into the “vast and endless sea above the surface of the Earth” that was dangerous, could fail, and from which they might never return. “We understood the substantial risks, we were willing to accept them because we believed that our goal was a worthy goal.”

He relived the moment he set foot on the lunar surface in July 1969, giving a dramatic account of manoeuvring the Eagle lunar module manually over car-sized boulders, past a 30-metre-wide crater and setting it down in a clear patch with only minutes of fuel to spare.

The former astronaut argued in favour of a permanent base on the Moon for scientific research, similar to stations now in Antarctica. He spoke in support of the manned exploration of Mars — although he warned this was “too difficult and too expensive with the technology we have available” today, so new techniques need to be developed. And this can be done with a return to the Moon.

Ultimately, he said, doing something unprecedented was a matter of ‘risk management’. You need to understand it, plan for it, and design and innovate your way to the goal with new ideas, engineering — and trust. “There were 400,000 people involved in getting us to the Moon, and we trusted our lives to many of them every day.”

But he’s convinced the seemingly impossible can be achieved. “When President Kennedy committed us to go to the Moon, we had eight and a half years to go and a cumulative total of 20 minutes in space,” he said, “We hadn’t even done an orbit yet.”

One woman, who as a young school student was punished for misbehaviour on that fateful July day by being sent outside — where she listened enviously as her gobsmacked classmates watched the Moon landing — told how she had cried at missing the historic telecast.

Armstrong gave her a hug. He’d missed it too, he told her, smiling.

In 2011, his calls for a return to the bold exploration of yesteryear were inspiring but fanciful; the age of space exploration had slowed to a shuddering pace, with no human having left Earth’s orbit for 40 years.

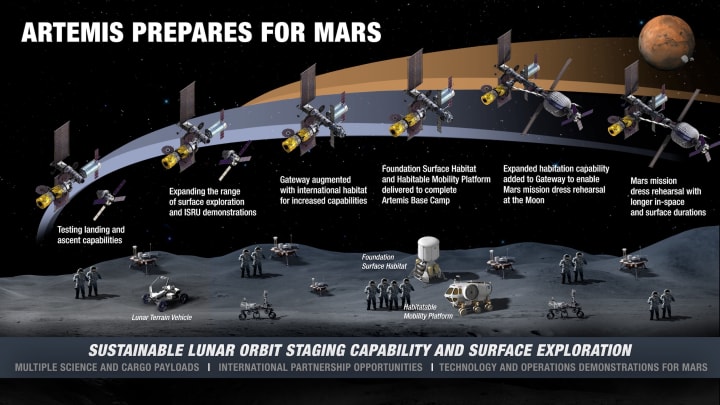

Yet today, establishing outposts on the Moon and using these to prepare for human missions to Mars is a reality — and the stated policy of his former employer, the U.S. space agency NASA, as well as China. NASA’s Artemis program aims to, from 2024, begin building a base camp on the Moon in stages, using a Lunar Gateway station in orbit, crewed landers, robot rovers and human habitats.

Key components include the Artemis Base Camp, a long-term foothold for lunar exploration of the south pole that will initially house four astronauts for a week. As infrastructure for power, waste disposal, communications, radiation shielding and landing pads are added, the base would help test human survival in the harsh environment — especially during the long, cold lunar nights — and develop technologies to mine and manufacture water, fuel and oxygen.

“When we say, ‘water on the Moon’, we are not talking about lakes, oceans or even puddles,” says Carle Pieters, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Lunar Orbiter’s principal investigator at Brown University. “Water on the Moon means molecules of water and hydroxyl that interact with molecules of rock and dust specifically in the top millimetres of the Moon’s surface.”

The base would have a terrain vehicle for astronauts to roam the surface, and later a ‘Moon hopper’ that could travel further and act as a live-in habitat for up to 45 days. Developing the habitats, mining operations and hoppers are seen as essential to perfect the technologies needed for eventual crewed missions to Mars in the 2030s and 2040s.

“After 20 years of continuously living in low-Earth orbit, we’re now ready for the next great challenge of space exploration — the development of a sustained presence on and around the Moon,” former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said, launching the program. “Artemis will … demonstrate key elements needed for the first human mission to Mars.”

At the dinner, Armstrong joked about his advanced years and — despite the fact he never flew into space again — that he would love to return to those days of yore. “You might ask me, ‘how does it feel to be the oldest person in the room?’ Well, I’m not thrilled about it, but I am encouraged by old timers who did great things as senior citizens.

“Galileo invented one of his greatest discoveries at the age of 73. Edison was still inventing in his 80s. Toscanini was still conducting at 87. So, if there’s a need to find someone to command a starship for a tour around the Solar System, I am available,” he quipped, to laughter and applause.

t seems hard to believe that we, as a species, once achieved such greatness, and did so with such men of valour and quiet modesty at the helm — and then let it all slide. But the tide is turning, and future that Armstrong foresaw is finally coming to pass.

Less than a year later, Armstrong underwent bypass surgery in Cincinnati to relieve coronary artery disease, developed complications and died, aged 82. Responding to his passing, then U.S. President Barack Obama described Armstrong as “among the greatest of American heroes — not just of his time, but of all time”, and said he had delivered “a moment of human achievement that will never be forgotten.”

I never did get to ask Armstrong a question, but I recall leaving that evening energised and inspired. Anything is possible if you put your mind to it, I felt. I know, because a man who walked on the Moon told me so.

And he was right.

Like this story? Click the ♥︎ below, or send me a tip. And thanks 😊

About the Creator

Wilson da Silva

Wilson da Silva is a science journalist in Sydney | www.wilsondasilva.com | https://bit.ly/3kIF1SO

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.