Jim Crow in the USSR

How Langston Hughes saw the Soviet Union and how it changed my life

We are all colonized.— marginalia in a library copy of Dominance Without Hegemony by Ranajit Guha, Indian historian

The reader of Langston Hughes’s writings on the Soviet experiment is bound to be confused. In the 1930s, during the peak of Stalinist repression, Hughes produced volumes praising the Soviet Union, particularly the Central Asian republics of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan where, as he writes in the second volume of his autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander (1956), “the majority of the [Soviet Union’s] colored citizens lived” (123).

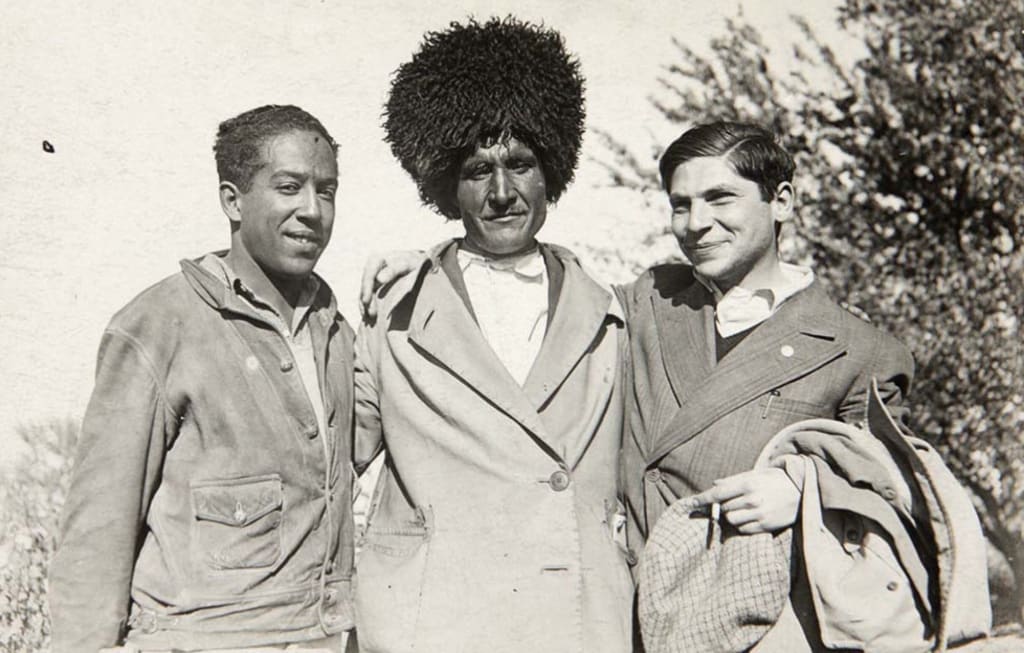

When Hughes penned these words, his sporadic involvement with the Communist Party and the Soviet project belonged to a former era. Two decades earlier, soon after his first visit to Uzbekistan, Hughes had published the chapbook A Negro Looks at Central Asia (1934), which had been commissioned by the Soviet government. In this incendiary work — notable for its contrast with Hughes’ later writings — Hughes compared the American South where “the color line is hard and fast, Jim Crow rules, and I am treated like a dog” to Soviet Uzbekistan where “Russian and native, Jew and gentile, white and brown, live and work together” (5–7).

The entire narrative of these sketches, originally published in the prominent Moscow newspaper Izvestiia, is structured by such contrasts. Images of Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama, where cotton has lost its value in the economy of the Great Depression and the factories are closed, are juxtaposed to an exotic Soviet socialist paradise where “textile mills now run full blast” (12).

Hughes’ scathing critique of sharecropping and indentured servitude in the American South is followed by a programmatically positive and, some might argue, willfully blind account of Soviet Central Asia where “everybody lives better than they did before” (26). At the time of Hughes’ writing, entire classes of people, such as the landholding peasants (kulaks) and the anti-Soviet nationalists (basmachis), were being dispossessed of their homes and livelihood. Yet Hughes viewed such events through a rose-colored lends: “Here, in the Soviet Union,” he enthusiastically insisted, “all the ugly barriers of race have been broken down” (18–19). Hughes predicted that Russian and Turkmen boys growing up in 1930s Central Asia would “never know the distorted lives full of distrust and hate and fear that we know in America” (19).

Such representations were entirely in keeping with the purpose for which the book had been commissioned. As the “note from the publisher” states: “These sketches show the reactions of a revolutionary poet and the son of an oppressed nationality to the achievements of formerly oppressed nationalities gained under the banner of the Soviets.”

The 1930s Soviet Union, particularly Central Asia, appealed to Hughes as the fulfillment of an otherwise unrealized and unrealizable American dream. A panorama of Uzbek students learning to read the Latin alphabet which the “mullahs who formerly controlled education deemed unholy” (25) is counterpoised by Hughes to the Bible Belt in the American South where “hundreds of Negros are lynched . . . and farces of justice like the Scottsboro trial are staged” (27).

The references to staged trials is interesting, given the numerous staged trials that preceded the assassinations of countless Soviet intellectuals. Hughes did not note — perhaps because he did not know, but also because he chose not to see — that the replacement of the Arabic script by Latin and later Cyrillic was part of a systematic campaign to suppress Central Asia’s precolonial Islamic past. Some of the Soviet practices that Hughes celebrated were a twentieth-century extension of Tsarist Russia’s colonial policies, not their negation and certainly not part of Central Asians’ liberation.

In Langston Hjuz She’rlari, an Uzbek translation of Hughes’ poems published in Tashkent in 1934, the same year as A Negro Looks at Central Asia, Hughes memorably eulogized the revolution of October 1917 that changed world history:

Then October

Came to clean

The world’s shoes,

To purify

The mercenary minds.

Look: here

Is a country

Where everyone shines,

Stomachs full

From their arms’ toil.

Under the Soviet sun.

If the Bolshevik Revolution “cleaned the world’s shoes” in Hughes’s estimation, the significance of this month was not so overwhelmingly positive for the millions of Soviet citizens who were killed, tortured, exiled to GULAGs, dispossessed of their lands, and deported. Hughes’s “October” resonates with the oeuvre of Vladimir Mayakovsky, a revolutionary poet whom Hughes cites as a source of inspiration in A Negro Looks at Central Asia (27).

Mayakovsky, the most eloquent herald of the revolution in its earliest phase, was ultimately one of its many victims: persuaded that the Soviet experiment had culminated in failure, he killed himself on April 14, 1930. Eight years later, Sanjar Siddiq, the poet who translated Hughes’ poems into Uzbek, was executed in a Stalinist purge.

Hughes’ unfounded optimism resonates with a near-contemporaneous Soviet pamphlet originally composed in Yiddish by S. Almazov but most widely disseminated in English translation as Ten Years of Biro-Bidjan, 1928–1938. Biro-Bidjan was created in 1927 as a secular Jewish homeland to protect Soviet Jews from the pogroms that haunted the tsarist period. It also facilitated the Soviet project of categorizing peoples according to their ethnicities.

Documentary on the creation of Biro-Bidjan (In Yiddish with English subtitles)

Criticizing the “capitalist-imperialist lands” that assimilate ethnic minorities and “erase the individual character of each minority group, destroy all vestiges of a native culture, and institute a melting pot, whereby to establish uniformity” (7), Almazov presents the Soviet Union as a new kind of political formation that has developed superior strategies for dealing with cultural, religious, and ethnic difference. His examples underscore the fortuitous convergence of technology and social development in the first modern republic designated for Jewish settlement.

Almazov makes his case for the success of Soviet policies by citing a speech delivered by Bolshevik leader Mikhail Kalinin in 1926 to a group of Jewish farmers. “The Soviet Union is not a country consisting of a large and specifically dominant nationality,” Kalinin affirmed.

Nor is it “a confederacy carrying with it the contents of the Russia of old.” Using the double meaning of “soviet” — both the name of a new political formation and a confederacy of equals — Kalinin declared that this newly formed country was “a union of all nationalities which have entered the soviet.” It was imperative to “find a place for every nationality” in this experiment in collective organization.

On October 25 1938, the year Almazov published his homage to Soviet Biro-Bidjan, Kalinin’s wife was arrested, tortured, and banished to a labor camp deep within the Central Asia he had extolled as a land of freedom and progress. As with Hughes’ eulogy to Soviet Central Asia, the contrast between the text and the world it claims to represent is jarring. Instead of trying to save his wife, Kalinin maintained his silence as Stalin and Beria executed the Soviet Union’s most gifted and courageous writers, poets, intellectuals.

Hughes’ silence is unlike that of these Soviet authors. His knowledge of Soviet realities, like his access to Uzbek and other regional languages, was limited. Nonetheless, or perhaps precisely for these reasons, his account of Soviet Central Asia echoes some of the Soviet authors’ limitations. How much did prior generations knew about the purges, executions, and massacres?

Hughes lived partly in ignorance of the atrocities that transpired in the country he so ardently eulogized. Sometimes his silence was strategic, and was not solely the product of ignorance. Knowledge of Soviet atrocities would have ruptured Hughes’ Central Asian narrative. It would have complicated the task of constructing Central Asia as a foil to American Jim Crow. Since this latter task was his primary goal, it sometimes led him to view the Soviet experiment through rose-tinted glasses.

Hughes’ silence is thus the result of the politics intrinsic to the art of storytelling. It is an inevitable product of a narrative encounter with another civilization. Illustrating that the stories we tell about our others are constructed almost by default to serve our selves, Hughes told himself and his readers a story that served the needs of 1930s and 1950s America.

Now it is time to tell a different story, one that recognizes that postcolonialism should extend to the Soviet Union. Such a story would bring together the disparate parts of the world in ways never seen before, or at least not since the Cold War. The troubling silences of so many other progressive intellectuals who whitewashed Soviet oppression during the years of purges and forced deportations produced a racialized doubletalk: Soviet Jim Crow.

Language as Colonialism

Soon after graduating college and moving to New York City, I walked into a building in West Harlem where I hoped to rent a room. I noticed a box covered with Cyrillic letters. It was an oversized box of books, packaged for shipment to Irkutsk, a city on Siberia’s easternmost edge, close to Japan.

The landlady who was subletting a room in her apartment introduced herself as Ludmila, a Slavic name that contrasted with her wide Asian eyes and amber skin. I complimented Ludmila on her elegant blouse. She told me she had recently purchased it from a boutique shop in Soho.

Ludmila seemed even more assimilated to American culture than I was. After a few minutes of small talk, during which she learned that I was pursuing graduate studies in Russian literature, we switched at her prompting to Russian.

“Have you been to Russia?” she asked me in Russian.

Having just returned from a sojourn in St. Petersburg during the magnificent White Nights, I launched into a recollection of the beauties of the Neva River, of the long boulevard Nevsky Prospekt, and of the Hermitage’s magnificent pastel façades. As yet ignorant of the full range of nuances attaching to the term, I asked Ludmila if she was Russian, using the term for Russian ethnicity, russkii. She smiled and nodded vigorously.

As it turned out, Ludmila was not Russian at all, even by her own accounting. Her affirmative answer to my question had been a polite means of accommodating my ignorance. Ludmila belonged to the Turkic-Altaic group called, in Soviet nomenclature, Khakas. The ethnonym Khakas has been widely contested, especially after the debate that burst onto the pages of the journal Sovetskaiia etnografiia (Soviet Ethnography) in 1992.

In a sharply argued polemic, the eminent ethnographer Victor Iakovlevich Butanaev noted that in the Khakas language the term khakas refers not to the people to whom the Soviet state assigned the name and who call themselves Tadar (from the Turkic self-ethonym, Russified as Tatar), but rather to the Kyrgyz, who were referred to as Khiagasy in the chronicles of the early medieval Chinese T’ang Dynasty.

On Butanaev’s account, the authentic name for the people now referred to as Khakas is in fact the entirely unrelated ethnonym Khoorai (alternately spelled Khongorai). The intermingling of Kyrgyz and Khakas respectively is revealed by the fact that medieval burial sites are today referred to in the Abakan region as Kyrghys sookter, meaning Kyrgyz graves.

Butunaev’s elucidation of the constructed nature of modern ethnic identities powerfully correlates with other post-Soviet regions, such as the northwest Caucasus, where the indigenous people who collectively refer to themselves as Adyga are called Circassians in English, after the Russian cherkasskii. This terminology derives from the fact that, as Charles King suggests, “early Russian informants probably gathered their nomenclature from neighboring peoples who used a variant of that term” (134).

Through processes that echo what Benedict Anderson has called the “systematic quantification” method introduced in the 1870s by census-takers across the Indonesian Archipelago, and which resulted in “the fiction of the census…that everyone is in it, and that everyone has one — and only one — extremely clear place” (170), the non-Russian inhabitants of the Russian empire’s outer-lying regions came to be defined, and not only linguistically, by the nomenclatures of their neighbors. These recently fabricated nomenclatures will likely persist long into the future.

This confusion of names speaks to the distributions of power that determine who has the right to speak and in what contexts in Russia’s Siberian territories. Ethnographer Kira Van Deusen has detailed the many ways in which contemporary Khakasians are products of Soviet modernity. Most live in concrete city apartment blocks similar to those I saw while passing through Grozny, far from their native villages.

They are “doctors, lawyers, carpenters, cooks, and herdsmen — but many are unemployed” (Van Deusen, 164). “Like everyone in Russia today,” Van Deusen notes, the Khakas “are concerned about whether they will receive their tiny salaries and pensions at all and about how to help their children get through school and live in a changed world” (164).

Practical exigencies do not leave much time for worrying about the future of Khakas culture. The younger Khakas generation partially understands but cannot speak the language they nonetheless call their native tongue.

This suggests that this language will become an artifact, catalogued in museums and analyzed in scholarship but dead to the world, by the close of this century. This gradual decay of Khakas culture, which is a result of state policies that could have been reversed, had produced a situation of spiritual alienation that bears in certain respects comparison to the Jim Crow of the American South.

Mistaken Identities

Nearly a decade passed before I realized just how strange my opening gambit — Are you Russian? — must have seemed to Ludmila. The Kuzhakov’s hometown was Abakan, in Central Siberia.

The city’s name, which in Khakas means “bear’s blood,” is crisscrossed by the Abakan River that flows into the Yenisei on its way to the Arctic Ocean. While Abakan is officially Russian territory, that does not mean that its inhabitants are Russian.

The difference between Russian citizenship and Russian ethnicity sounds esoteric to an American ear. American culture lacks nuanced distinctions between ethnicity and the state. In the United States, anyone who has citizenship or is naturalized is automatically “American.”

In the former Soviet Union, including the Russian Federation, the difference between being a citizen (rossiiskii) and a member of an ethnic community (russkii) is as crucial as one’s name, one’s livelihood, and one’s identity. It makes all the difference when it comes to education, employment, and even to such mundane things as making friends and falling in love. Russkiis marry russkiis, while rossiiskiis must become russkii if they wish to ascend the ladder of social success.

Vladimir, the son of my New York landlady, taught me a lot about his native country. What he taught me changed my life. I have spent much of my life immersed in the culture, language, and literature of the country where Vladimir was born and where Langston Hughes traveled in search of a refuge from Jim Crow America.

Yet certain aspects of this country’s history continually elude me. Unlike me, Vladimir could never bring himself to say that he despised Russians, although he was terrified of returning to the country that was at once his homeland and an alien territory. Years after our parting, soon after the birth of his first son and his marriage to another American woman, Vladimir told me that he would be the last Khakas in his lineage.

Russian was the language of our love. It was the medium of our shared intimacies, and of his most painful memories. Does this mean that Russian was Vladimir’s native tongue? That depends on how “native” is defined. It also depends on who has the power to define it.

I was about to write that Russian was Vladimir’s native language, when I remembered a day we spent together searching for an apartment in New Jersey. Vladimir was quiet as usual while I negotiated with the aggressive real estate broker, who clearly was not new to the business of selling homes to homebuyers on a budget.

Vladimir had only one question, which he reserved for the end of our meeting with the real estate agent. He asked in fluent English how far the Newark apartment was from the train station. Without so much as glancing in his direction — although he was standing right in front of her — the real estate broker asked me where “he” was from and what language “he” spoke.

“Americans,” I wanted to shout back, “are vulgar and stupid when it comes to relating with foreigners.” Instead I opted for politeness. I explained that “he” was from Russia and that “his” native language was Russian. In the regions of white America that we were traveling through, migrants existed only in the third person.

“No,” Vladimir interrupted my conversation with the real estate agent, “my native language is not Russian. I am Khakas.”

Surprised as I was by his reaction, my first instinct was to disagree. I tacitly assumed that my linguistic norms defined the terms by which anyone, Vladimir included, must be measured. In English, “native” refers to the language you speak best. It is a matter of destiny rather than choice.

A Chinese person who does not speak Chinese cannot claim Chinese as their native language. A Punjabi who speaks Hindi better than Punjabi is by definition a native speaker of Hindi, ethnic nuances aside. The native language of a member of the Choctaw Indian nation is English, if that is the language they speak best.

Such logic possessed hypothetical cogency to my untutored ear, but it did little to elucidate the ambiguities of Vladimir’s identity. Vladimir — who never spoke of being Khakas, who had dedicated his adult life to cultivating a self his Soviet education had denied him — protested my claims. The shallowness of my reaction stuns me as much as does my inability at the time to grasp what was so obvious for him.

I can only claim to have been blinded by the same malaise that marred Hughes’ whitewashing of Soviet discrimination during his journey across the new Soviet Union. Whatever important work Central Asia did for Hughes rhetorically as a foil to American Jim Crow, this strategic contrast had the negative effect of preempting the poet’s ability to perceive racial discrimination in the Soviet Union.

A native language, Vladimir taught me, is not the language one speaks best. It the language in which one is most at home, in which one can be most fully oneself. Vladimir could not be at home in the language that had colonized him.

References

Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander (New York: Rinehart and Company, 1956).

Langston Hughes, A Negro Looks at Central Asia (Moscow : Co-operative Pub. Society of Foreign Workers in the U.S.S.R., 1934).

Charles King, “Zalumma Agra, the “star of the East” (fl. 1860s),” Russia’s People of Empire: Life Stories from Eurasia, 1500 to the Present, Stephen M. Norris and Willard Sunderland, eds. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012).

Kira Van Deusen, The Flying Tiger: Women Shamans and Storytellers of the Amur (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press — MQUP, 2001).

About the Creator

Rebecca Ruth Gould

I am author of the award-winning book Writers and Rebels: The Literature of Insurgency in the Caucasus (Yale University Press, 2016). My Wikipedia page.

Subscribe to my YouTube Channel Poetry & Protest. ⬆️

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.