It’s Possible to Become Conscious in Your Dreams

The Science & Practice of Lucid Dreaming

Imagine that you could have any experience that you desired. What would you do? Maybe you would jump into the air and take flight, meet your favorite celebrity, or perhaps you would engage in something a bit more risqué. As adults, many of us seem to feel that dwelling on our fantasies is not productive and, therefore, not worth doing. It certainly makes sense not to waste time thinking about something that will never happen, but what if there actually is a way to fulfill literally any fantasy you might have? As it turns out, there is and it’s called lucid dreaming.

A lucid dream is simply a dream, during which the dreamer knows that they are dreaming. It has been scientifically proven since the 1970s, has since been replicated and peer reviewed, and, best of all, it is a learnable skill. As far as we know, everyone is able to learn how to become conscious in their dreams. I have been a lucid dreamer since 2009 and I learned how to do it after spontaneously having a few lucid dreams of my own. I quickly became active in the online lucid dreaming community and, since then, I have created numerous pieces of content about the subject, from videos to books and articles to audio courses.

My passion for lucid dreaming has inspired me to make hundreds of instructional videos on YouTube, and to participate in the creation of hundreds more in other collaborative projects. I have written articles on top lucid dreaming websites, but I also run my own website where I blog about lucid dreaming, too. In the past, I had been frequently sought out by companies to test their lucid dreaming products, where my policy of total honesty in my reviews actually led to me exposing a few scandals. My first book, The New Frontiers of Lucid Dreaming, is the world’s first lucid dreaming guide to have been made specifically for experienced practitioners.

Suffice it to say that the subject of lucid dreaming is one I am deeply passionate about. As such, I would like to take this time to impart as brief and complete an overview of lucid dreaming as possible; what it is, its science, and how to do it. This will by no means be exhaustive, but it should be comprehensive enough to use as a general reference to get you lucid dreaming, if you so choose. However, if you want to know how to make lucid dreaming a long term part of your life, you will need to do some research of your own, but I highly recommend the books Lucid Dreaming: The Power of Being Awake & Aware in Your Dreams, by Dr. Stephen LaBerge, and Are You Dreaming?: Exploring Lucid Dreams: A Comprehensive Guide, by Daniel Love.

Understanding Lucid Dreaming

At its core, lucid dreaming is a type of mindfulness practice, though it still differs quite drastically from traditional mindfulness practices, like most meditative techniques. The lucid dreaming practices are mindfulness based, because they require that the individual teaches themselves how to either notice when they are experiencing a dream, or learn to transition into sleep, and dream, wakefully (yes, this is possible). Many of the components of lucid dreaming require direct observance of one’s experience, making it comfortably fit into the mindfulness category of practice.

The experience of lucid dreaming can be confusing for people to understand. Often, new lucid dreamers aren’t sure if they had their first lucid dream or not. As the definition states, any dream in which the dreamer knows that they are dreaming, for any amount of time, is a lucid dream. Sometimes this can be for only a moment, sometimes it can last the entire dream, but, either way, as long as the dreamer knows the reality of their situation during the dream itself, the dream is lucid.

The quickest way to explain what lucid dreaming is like, is to say that it varies just like it does in waking life. We wake up groggy, once we get going we feel more alert, later we have lunch and hit an energy slump, making it get harder to focus and stay awake, then we get a boost of energy to finish out the day before we come down to sleep in the evening. Likewise, there will be times when you will realize that you are dreaming and your mind will be foggy and you won’t have much control. Other times, you will feel as if the world in your dreams is as real and vivid as the waking world. In these instances, you will have control over yourself in the dream, and often over some aspects of the dream itself (this is called dream control). There are even things one can do to increase their level of lucid awareness once one has realized that they are dreaming, which are called stabilization techniques.

As far as the first-person, visceral experience of lucid dreaming, it’s just like having any other experience and comes in gradients. Most often, the level of awareness will be low and things will be as foggy in the moment of the dream as they are upon being remembered when you wake up. Essentially, you will know that you are dreaming and be able to control yourself and some aspects of the dream to varying degrees, which increase with your level of awareness. You can build the skill of becoming more aware in your dreams and, in which case, experiences can be made to feel more wake-like and, as such, produce more vivid memories as well.

Overall, lucid dreams still feel like dreams, because they are, the goal is to either learn how to recognize the differences in the cognitive experience, between a dream and being awake, or to learn how to stay awake while you let your body go to sleep and into a dream. We will discuss these two different methods of entry into the lucid dream experience more fully later on.

How we Know Lucid Dreaming is Real

Lucid dreaming has a long history, with references that date back to Ancient Greece, and it has even been utilized in certain spiritual traditions, like some fringe sects of Hinduism and Buddhism. I will, by no means, provide an extensive history of the subject here, but rather intend to speak about how it was verified scientifically, by whom, and what we know about it, at this point.

The term “Lucid Dream” was coined by the Dutch psychiatrist Frederik van Eeden, in a 1913 article entitled 'A Study of Dreams.' The name has stuck and, as such, it’s the term we still use to this day. Although van Eeden coined the term, he is nowhere near as renowned or beloved by experienced lucid dreamers than an earlier dreamer, who is Marie-Jean-Léon, Marquis d’Hervey de Saint Denys. Saint Denys was a French sinologist (one who studies China, its history, language, and culture), but the work for which lucid dreamers admire him is his 1867 book, first published under a penname, Dreams and the Ways to Direct Them: Practical Observations.

This is a book which Sigmund Freud had tried to get his hands on, but was unable to find. Undoubtedly, if he had been able to obtain the book, it would have been a major contributor to his thinking on dreams, and also might have made the subject much more popular today. Unfortunately, Freud’s inability to locate Saint Deny’s book was a misfortune for us all, considering the state of modern lucid dream research and the popular opinion of the subject today.

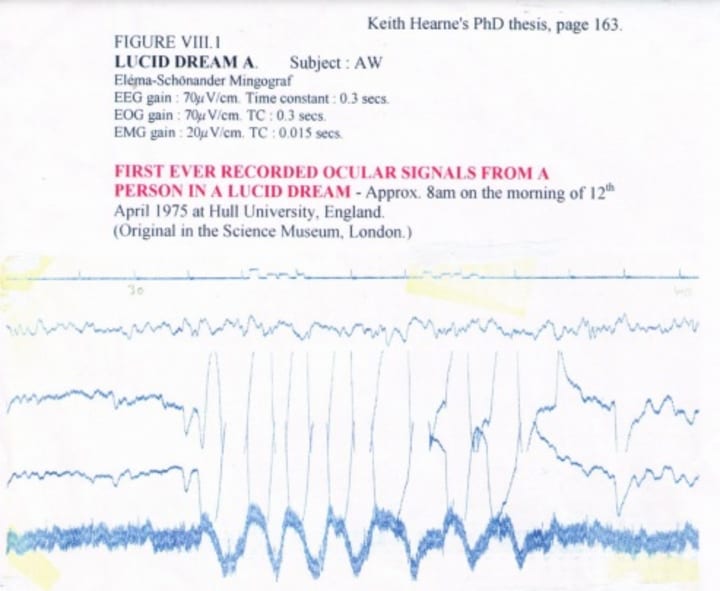

The formal research of lucid dreaming officially began with Dr. Keith Hearne, in the 1970’s, with his doctoral dissertation on lucid dreaming, Entitled ‘Lucid Dreams: An Electro-Physiological and Psychological Study’ which was submitted in 1978 at the University of Liverpool, in England. For this dissertation, Hearne worked with a lucid dreamer, by the name of Alan Worsley, monitoring him using Polysomnography or PSG, while he slept. Polysomnography is a combination of several techniques used in sleep studies to monitor various aspects of our physiology. Not only does it monitor brain waves via EEG, but also eye motion, EOG, muscle tension, EMG, and breathing, ECG.

With this, Dr. Hearne was able to verify lucid dreaming scientifically, proving that it is possible, by obtaining data during Worsley’s lucid dreams. How they did it was a stroke of genius. They decided upon a pattern of eye movements that would act as an obvious signal, which Worsley would use to communicate when he had become lucid in one of his dreams. The theory was that, since the eyes move during REM sleep (the stage of sleep where most dreams occur), this might correspond to where the dreamer’s gaze is within the dream. If this were so, it would mean that the dreamer could control the movement of their eyes, by dint of being lucid. This theory turned out to be correct.

So, by monitoring Worsley’s brain waves via EEG, Hearne was able to show that Worsley was dreaming at the time the predetermined eye signals were recorded, via EOG. The eye movements are usually quite random during REM sleep, but by moving his eyes in an intentional left and right pattern several times, Worsley sent the first ever signal to the outside world, from within a lucid dream, confirming that lucid dreaming is real.

Hearne has since often publicly commented that it was like “getting a message from another universe.”

Unfortunately, Hearne’s work was never published in a scientific journal, so he rarely gets credit for his breakthrough. Instead, the credit usually goes to Dr. Stephen LaBerge, for his thesis, which occurred two years later, entitled ‘Lucid Dreaming: An Exploratory Study of Consciousness During Sleep,’ purely because he was able to get his work published. Although, one should not discount LaBerge’s work, because, in following studies, he developed the modern lucid dreaming induction techniques that we still use today, which he was able to prove were effective, logging several lucid dreams of his own, in the process.

There are only a few dedicated lucid dreamers who give Hearne the credit due. Among these is Daniel Love, who founded Lucid Dreaming Day, which is on April 12th of every year, to spread awareness of Hearne's contribution and to celebrate the subject itself. Today, it’s quite common for people in the online lucid dreaming community to do something special on this day, commemorating the day of Hearne’s discovery, which I think is great.

Regardless, LaBerge did create the modern lucid dream induction techniques, while also classifying them into two categories: Dreams that become lucid while one is already dreaming, called Dream-Initiated lucid dreams, or DILDs, and dreams that begin lucidly, because the dreamer goes directly from a waking state, into the dream state, with consciousness already present, called Wake-Initiated lucid dreams, or WILDs. This is where we start to get into how lucid dreams are achieved, however I’d first like to mention a few other recent studies which are monumental for lucid dreaming.

The first of which is a 2009 study by Ursula Voss, and others at Frankfurt University, called ‘Lucid Dreaming: A State of Consciousness with Features of Both Waking and Non-Lucid Dreaming.’ This is the study that established that lucid dreaming has differences from purely dreaming and purely waking states, citing differences in brain waves and more activity in the frontal areas of the brain than ordinary dreaming.

More specifics about the activity within these frontal regions were discovered in a study by Elisa Filevich, and others, which was published in the Journal of Neuroscience in 2015. The article, ‘Metacognitive Mechanisms Underlying Lucid Dreaming,’ looked for neural correlates involved in lucid dreaming, and showed increased activity within the prefrontal cortex, specifically in Brodmann’s Areas 9 and 10, which are associated with overriding automatic responses, inductive reasoning, sustained attention, and are implicated in metacognition, among other things.

In other words, lucid dreaming has been firmly proven to be a real experience that people can learn to have on a regular basis. More recent lucid dreaming studies have been investigating the efficacy of specific lucid dreaming induction techniques, most notably the International Lucid Dream Induction Study (ILDIS), which compared 5 different induction techniques, finding LaBerge’s Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreaming (MILD) technique to be the most effective of those compared. Still, there are dozens more techniques left to test, as several lucid dream authors have created their own, myself included. In the coming years, I expect studies to uncover the principles which these techniques rely upon, which will lead to more effective induction techniques.

How to Lucid Dream

There are two methods of entry into a lucid dream, called Dream-Initiated and Wake-Initiated, and there are techniques available for achieving both. For dream-initiated lucid dreams, most of the things we do are based on mindfulness and prospective memory, because we are, for the most part, doing things during the day to train ourselves to question reality, so that we begin to do so in our dreams. These require little use of induction techniques, meaning that we can go to sleep normally and not disrupt our sleep too much and still be successful. Wake-initiating, however, is heavily reliant on induction techniques and disrupting our sleep.

It’s also necessary to learn additional details about the sleep cycles, as well as experiment with nightly awakenings to understand how it feels to wake up from certain stages of sleep, so that you can judge if you have woken up from a stage of sleep that makes it likely for your induction attempt to be successful. As you can see, wake-initiating is the more complex style of lucid dreaming and requires much more effort and patience to get right. Even still, most lucid dreamers who rely upon wake-initiation still partake in practices which are designed for dream-initiated lucid dreams.

1. Keep a Dream Journal

The dream journal is exactly what it sounds like. It’s a journal in which we lucid dreamers write our dreams down, every day. There are no successful lucid dreamers who don’t keep a daily dream journal. The reason this is required is because it trains you to remember more of your dreams (this skill is referred to as dream recall). In a full night of 8 hours of sleep, people will typically have 4-6 dreams. Although, it’s quite common for those who do not journal their dreams to only remember 1 or 2 dreams a night, if any. Someone with good dream recall will remember most, if not all, of their dreams, and the dreams they do remember will be recalled with more full detail. Dream journaling will, over time, improve our dream recall, which is absolutely necessary for lucid dreaming.

Without the dream journal, it’s possible that we could have lucid dreams, but completely forget them. This has happened to other lucid dreamers I know, myself included. We know it happens, because, occasionally, we will write our dreams down in the morning, remembering no lucid dreams, and then, later in the day, something might jog our memory about the lucid dream we had the night before, but had forgotten. There are likely more times when even trained lucid dreamers have completely forgotten their lucid dreams, and this is absolutely guaranteed to occur if you do the other lucid dreaming practices, but fail to keep the dream journal.

2. Do 10+ Reality Checks a Day

A reality check, also called a critical state test, is another lucid dreaming practice, geared toward dream-initiated lucid dreams. This is also much like it sounds; something we do, while awake, to check the state of our reality, to discover whether it is waking life or a dream. This often sounds counterintuitive to new lucid dreamers. How could one honestly begin to question if they are dreaming, when they are clearly awake? This assumption, however, is flawed, because we are regularly fooled by our dreams each night.

A lucid dream is a dream in which you know you are dreaming and, as such, this is an obvious difference from ordinary dreams, which share the quality of not questioning our situation with waking reality. If one wants to have dream-initiated lucid dreams, we have to get into the habit of questioning whether or not we’re dreaming, and the only way we can do this is to train the skill while awake. This means we have to learn to foster the mindset that we could be dreaming, while awake, which reality checks help us do.

Building the reality check habit will, over time, begin to produce a markedly different cognitive experience than we ordinarily have during the day. Reality checks are about little bursts of mindfulness, during which we prove that we are either awake or asleep, and break the normal auto-pilot mode of being, to which we are a slave, both while awake and in ordinary dreams. When we build this skill, it will occur within our dreams. Often, we will begin to do reality checks in our dreams, causing us to go lucid, which is the intended result, but it’s also quite often that the mindfulness aspect itself occurs without the reality check, meaning that DILD lucid dreamers often become lucid without any prompt within the dream, purely because the cognitive aspect of the reality check occurred.

A good reality check is one that will reliably provide a different result in dreams than it does in waking life, and it is only a true reality check if this mechanical part of the check is combined with the mental aspect of truly questioning whether or not you are dreaming, with the explicit understanding that the moment you are in, regardless of how wake-like it seems, could just as easily be a dream. In fact, there is a 1 in 6 chance of it. Regardless of how silly it might seem, it’s actually rational to question whether or not you’re dreaming, because you’re fooled by your dreams every night.

This is why I preface every reality check I do with telling myself that I could be dreaming, while allowing myself to marvel at the detail of my experience. I then tell myself what check I will do and what the result will be if I am awake, versus the one I will get when I am dreaming. I will then do the action of the check, and repeat the meaning of the result to myself. I do this several times in a row and count it as one reality check. This helps to build the right mindset.

Bearing all this in mind, I’ll explain some of the best reality checks I know. The most reliable reality check is what is called “the nose-pinch test.” This is when you pinch your nose, with your mouth closed, and attempt to breathe through it, both inward and then outward a few times. This check works because we have control over our breath in dreams, and, while dreaming, we will be pinching a dream nose, while our physical nose will be unobstructed. This means that you can breathe through a pinched nose in dreams.

As a lucid dreamer of over 10 years, I have only not been able to breathe through a plugged nose in one of my dreams, and it still resulted in lucidity because I was questioning my reality and noticed the other differences in my experience. Another reality check that I swear by is counting my fingers, looking away, and looking back to count them again. This works for me because, every time I look at my hands in my dreams, there will be some difference, whether it be in the number of fingers, or some other change.

Things in dreams often have noticeable differences between glances. The dream is only rendering what we see at any given moment and, when we look away and then back at something, it is required to render it again. This second render is not exact to the first. That is why the finger counting check and the text reading check are effective. The text reading check is another popular check, which is quite reliable, and follows the same principle. You look at something with writing on it, look away, and look back, keeping an eye out for any differences. Sometimes, even looking at text will make people go lucid, because things are quite difficult, if not impossible, to read in dreams.

The logical, reasoning parts of our brains are less active in dreams and this makes reading incredibly challenging, although this varies between people. Some people can read better than others in dreams, while some people’s hands look more ordinary than others in dreams. There are many individual differences between people and how they dream and, as such, the checks that are reliable for one person are not necessarily reliable for another. These subtle differences permeate the entire structure of the lucid dreaming practices, such that each person will need to find what works best for them, in many aspects of the practices.

Since my hands are always different each time I look, in my dreams, I have long paired the nose pinch check with the finger counting check. In waking life, I will count my fingers, plug my nose and attempt to breathe through it, and then count my fingers again. I do this several times in a row until I am satisfied, which has worked quite well for me. You might end up doing something different, so be sure to experiment with different checks for yourself.

3. Use Induction Techniques

Now that we’ve gone over the basic dream journal and reality checks, the discussion is going to get more complex as we talk about induction techniques. In the interest of saving time, I will only be describing the MILD technique, because it has been shown to be the most effective for beginners in the lab, in the short term. Induction techniques are different from the daytime practices, because the idea is that we’re trying to induce a lucid dream, in the moment. We are actively trying to make a lucid dream happen, rather than doing things that support it occurring later. With dream journaling and reality checks, it’s as if we are trying to train ourselves to notice when the dominoes have begun to fall, while induction techniques are the attempt to push the first domino over ourselves. We are affecting the change.

To do this, it requires experimentation, planning, practice, and quite a bit of patience, for the most part. Induction techniques are meant to be attempted after what the lucid dreaming community calls “Wake Back to Bed.” Wake back to bed is when you set an alarm to go off after a certain amount of time into your sleep schedule, which is different per person, and stay awake for several minutes, often doing something to stimulate the mind, but not the body, before going to bed to try your induction technique.

Wake back to bed should be positioned such that you wake yourself up on the back-end of the deep NREM-3 sleep stage, or very early into an REM phase. This way, you become almost guaranteed to enter into REM dreaming sleep, when you go back to sleep. Scientifically, it should be noted that some dreams do occur outside of REM sleep, but the majority of them occur in REM and, as such, have a strong correlation with it.

In order for induction techniques to work, we have to be well attuned to our sleep schedule so that we can plan our nightly awakenings at a time that makes it reasonably possible that our attempts will work. This is different per person, because our sleep schedules are all just a little bit unique. Mainly, people tend to set an alarm sometime between 4-6 hours after sleep, because the REM stage gets longer each time it comes around, so the dreams we have later into our sleep will be the longest. Still, this takes a lot of work to find out and, once we know exactly when we should wake up, it also takes work to figure out how long we ought to stay up, as some of us can stay up as long as 2 hours before trying an induction technique and still be successful, though most only stay up somewhere between 15 and 45 minutes.

However long it takes you to typically shake off the fog of sleep is a good guide for how long you ought to stay awake during Wake Back to Bed. You want to be alert, but not so awake that you can’t easily get back to sleep, while also avoiding bright lights, especially electronics and the morning sky, as these make it difficult to return to sleep. Blue spectrum light signals to your brain to stop producing the chemicals required for sleep, and begin producing those associated with waking up for the day.

The Mnemonic Induction of Lucid Dreaming works as follows:

When you’re ready to attempt to induce a lucid dream, lie down in bed and set the intention that you will realize when you’re dreaming. This is vague, but it is what the original technique recommends. I look at this as simply expecting that your attempt will work, as I believe this intention is actually set by what follows. You will then begin repeating a short phrase to yourself, in your head, that communicates the idea that you will realize when you are dreaming. Different people use different phrases, and I believe that some phrases communicate the idea better than others, to certain people.

This is an area which you will have to experiment with, but simply repeating “I will realize when I’m dreaming,” is a good starting point for your MILD affirmation. In the future, you will want to pay attention to what your first thoughts are when you realize you are dreaming, as this is a perfect phrase to use as your MILD Affirmation. For example, I tend to think “I’m in a dream,” when I realize I’m dreaming, so I tend to use phrases like “I will realize when I am in a dream.” Your first thought when going lucid might be “I’m dreaming,” in which case “I will realize when I’m dreaming,” would be a better option.

Now you will repeat your phrase to yourself as you allow yourself to relax and, once you feel that you’re closer to sleep, usually when it gets hard to keep repeating the phrase, you will then switch to imagining yourself within the last dream you remember having. Think about that dream, playing the memory back to yourself, while then imagining yourself realizing it’s a dream. If you find yourself at the end of this last exercise, but still not asleep, begin repeating the phrase to yourself again and, when you feel like you may fall asleep again, begin imagining your last dream, and that you are becoming lucid in it. Eventually, you’ll fall asleep and you will either enter into the dream lucidly, or you will fall asleep and find yourself realizing you’re dreaming once the dream has already been happening.

Once You’re Lucid

Of course, this is the time to have fun! However, the first thing lucid dreamers do when they become lucid is to stabilize it with “stabilization techniques,” so that they can avoid waking up immediately. The essence of stabilization is to interact with the dream, through your senses. Typically, this will mean engaging our sense of touch, but it is not limited there. Most people use a stabilization techniques like rubbing their hands together, clapping, or making an attempt to feel the texture, firmness, and small details that may be present when other objects are touched in the dream.

As you traverse the dream, you might find that it takes effort to maintain your awareness and this is normal. The lucid dream experience is unlike any other and it occurs at a time during which our brains naturally keep certain parts of our minds more docile. If we don’t keep engaging the dream, we are very apt to return to the natural state of dreaming, or to wake up. For this reason, I’ve found it helpful to always engage my sense of touch in the dream.

Sometimes I run my fingers against the walls, other times I pick up an object to carry with me to occasionally focus on how it feels, other times still I will rub my thumb against my fingers, so that I have one hand free to do other things. Constantly engaging this sense of touch and calling your attention back to it, as you might with your breath while meditating, is an incredibly useful tool for maintaining awareness in lucid dreams. So, when you first become lucid in a dream, you should not fail to stabilize it. To do this, engage as many of your senses as possible until you find which actions work well for you.

I hope you have been fascinated by learning about the subject of lucid dreaming. It is an experience like no other and one that is still largely a mystery. It's a space that exists only within ourselves, in which we can do nearly anything we can imagine. The possibilities are endless. Anyone can learn how to lucid dream for free, so get out there and start paying attention to your dreams. Some of the most exciting times you ever have in your life, just might be when you are asleep.

About the Creator

James S. Bray

Writer of fiction and non-fiction alike 🖖

Check out my book: 'The New Frontiers of Lucid Dreaming' on Amazon!

Connect with me elsewhere: Linktree

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.