From the Cave to the Page

A brief history of writing.

Language has been a major part of our social evolution, completely altering the course of human life. We have evolved from a series of grunts and gesticulations to a deeply articulated language. What is even more impressive is that we have taken our myriad vocalizations and learned to transfer them to the page. Writing has come a long way, from the cave wall to the Facebook wall. The evolution of writing is a complex narrative of slow progression: from rudimentary figures drawn on stone with blood and chalk, to lines etched in clay, to complex pictographs carved into temple walls, to fully formed words and sentences being combined into volumes of text, to the complex world-building of binary code.

The use of pictures to convey meaning, such as the cave paintings found in Altamira, Spain can be traced all the way back to the Paleolithic era, that period of time known to grammar school students as the stone age. These types of cave paintings were not true writing systems, however, because the depictions were rudimentary and varied from location to location. The artists in these cases were just drawing what they saw in real life. Even so, the cave drawings do tell us something about the evolution of language. As time wore on and man became more sophisticated, rudimentary drawings were no longer sophisticated enough to convey all that humans wanted to report. Later writing systems did use real-life objects as symbols, but those symbols were standardized to a certain degree, so they appeared throughout certain regions with little variation. Probably the first true writing systems were not really writing systems, at all. Rather they were simple mnemonics, devices like the Quipu, a census tool consisting of multi-colored wool cords. Used mostly in the Andes, the Quipu was utilized as a means of tracking animal herds or human populations. This was not a writing form exactly, but it demonstrates the human capacity and desire to understand and/or control the world around them.

An inexorable connection exists between language and numbers because language and numbers are an abstract expression of real-world concepts. The need for counting would not have arisen had humans not found the need to catalogue or record the items and events in their world. This probably began simply, as in how many berries were gathered and how to divide them up amongst the tribe. Hierarchies meant that some individuals would enjoy more than other individuals would, so the piles of berries were divided unevenly. It would not have taken much effort for the human brain to process that pile A was larger than pile B. What is an extraordinary leap forward for the brain is that humans found ways to use this intrinsic concept to improve their existence.

In Sumeria, where it is believed the first pictographic writing system appeared, traders would also use certain mnemonic devices in their everyday practices. For instance, they used clay figures, often rudimentary shapes, to represent the items being traded. If two lambs were traded for one goat, then one herder would transfer his lamb figurines to the other herder and would receive a goat figurine in return. As the human population, and by extension the livestock population, grew, the figurines would have inevitably proved impractical. This led to Sumerians using clay tablets, into which they would carve symbols. The symbols initially consisted of simple counting lines or hash marks. As Sumerian society grew more sophisticated, however, the writing system began to incorporate symbols that were representative of real-world objects.

The clay figures used for trading would have been translated into two-dimensional symbols. Writing became important to the Sumerians because keeping an inventory of food or animals was integral to the overall success or failure of the population. This concept applies to all populations, large or small, then and now. Survival depends on not only the continued acquisition of food through trade and farming but also the stockpiling of food and resources for times of famine or drought. It was more beneficial to the growth of the Sumerian city-state to keep accurate tabs on food production as well as food surplus (Kramer, 1971). The survival of early populations was precarious, so in terms of inventory and stockpile, helped the Sumerian society reach a previously unprecedented apex.

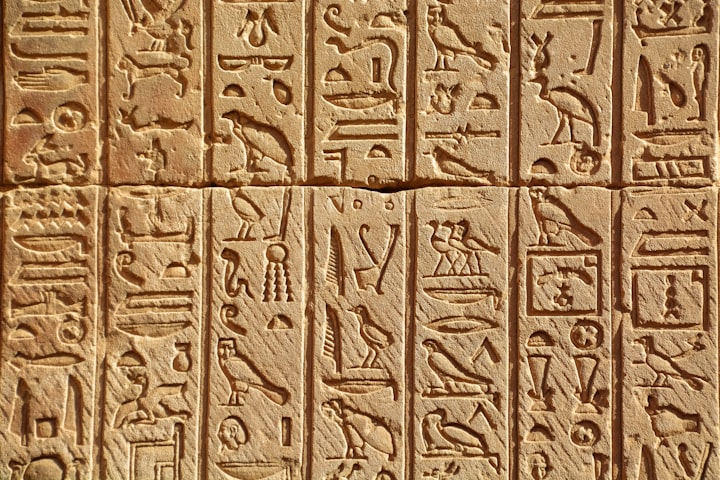

The shift from basic mnemonics to the picture writing system of cuneiform occurred around the 35th century B.C. Cuneiform as language began as a strictly pictographic writing system. Glyphs or symbols were used to represent numbers, basic objects, and eventually verbs. Soon after verbs were incorporated, cuneiform became more sophisticated, evolving beyond primitive concepts. The writing system began to incorporate ideographic symbols. These symbols were not based on objects in the real world; they were instead representative of complex ideas, such as emotions or spiritual beliefs. An example of this can be seen in the Egyptian hieroglyph for foot, represented by a leg glyph, and the cuneiform symbol for walk, also represented by a leg glyph. One is a specific object found in the real world, the other is the action that object performs. The second concept is more complicated.

The more sophisticated the society became, the more they began to adopt these ideographic forms. While ideographic writing still falls under the overall category of picture writing, it expands on the limitations of pictograms. An ideographic system, instead of using a pictogram of the god of death might instead portray the overall concept of death with a commonly recognized ideogram. This can be demonstrated in a number of ways. Schoolchildren today can identify tombstones as having to do with death, and in Chinese writing, death is a specific character representing an idea about death, but Chinese symbols are not generally understood outside of China.

There are nearly universal symbols of death, such as the crow, known across many cultures as a carrion bird and a harbinger of death. The problem with the crow, however, is that there is nothing to differentiate a simple crow from the more profound concept that it represents. Therefore an effective symbol would be needed to encompass death as an overall concept, one that could not be mistaken for anything else, for death is far too important a concept to be misunderstood. But misunderstandings in the picture writing systems were inevitable because the ideographic and pictographic systems did not allow for growth.

Death or dying can be associated with other concepts, such as transition or even weariness. In the modern world, the phrase “dead tired” indicates that someone is extremely exhausted and would like to rest. If this were written using a picture writing system, and if the symbol for dead and tired were grouped next to each other, the phrase could be easily misinterpreted.

Take Egyptian Hieroglyphics as an example. If a letter from cousin Ibrahim in North Alexandria to cousin Ishmael in South Alexandria were written to convey that Ibrahim’s son, Isaac, was dead tired and needed help tending sheep, Ishmael might think it meant Isaac fell asleep and was subsequently trampled to death by sheep. Suddenly, Ishmael, a rabbi, is planning a funeral for his beloved nephew.

The writing systems were so inflexible that it was almost impossible to incorporate new uses for symbols because a symbol usually meant what it meant and there was no middle ground to be had. Of course, the example of Ibrahim and Ishmael is extreme, but it illustrates at least one major problem with the picture writing system. Unfortunately, it is not the only major problem.

Inflexibility was just one part of a larger problem regarding picture writing systems. The greatest problem the system created was that it was virtually inaccessible to anyone who did not have teams of scholars at their disposal. If one object, say a poplar tree, was represented by a specific symbol, then all forms of trees would be known by their specific symbols. This would add up to a lot of tree symbols. The diversity of the symbol might not seem important - a tree is a tree is a tree - but specific trees might have been used for specific purposes, then having a symbol for each type of tree becomes immensely important. Because of the need for specificity, picture writing systems would grow vast, so specialized scholars were needed to translate the pictures. Cuneiform writing, for instance, became a niche writing system for astrologers. In other words, it became a fringe element, neither adding nor detracting from the culture, but growing stagnant in the hands of mystics and soothsayers.

Egyptian hieroglyphs, on the other hand, did not become a fringe element. Instead, they became the writing system of the elite. In their case, specialization of language only served to further the class divide. The poor, because they could not read, would find it nearly impossible to rise above their station. Thus the rich would remain rich, creating the kind of social elitism that usually ends in revolt. The writing was so elite, in fact, that there was some amount of difficulty finding a primer, or a key to the language. Fortunately, the discovery of the Rosetta stone, a tablet with the same message written in three languages (including Egyptian pictograms and Greek logograms), helped unlock the secrets of the Egyptian language. The expansiveness of ideographic and pictographic codices and the socioeconomic divide they created probably sped along the development of more flexible writing systems, such as the transitional Phoenician alphabet.

The Phoenician alphabet is known as an abjad alphabet because, while it contains a number of consonants, there are no vowels. The vowel sounds, in the case of an abjad alphabet, are phonetically supplied by the speaker. Because the Phoenicians were such proficient traders, their alphabet was used throughout the Mediterranean, so much so that the Greeks adopted it as their own. Yet the Greeks did not maintain the language in its pure form. Instead, they added a number of elements, not the least of which were vowel sounds. The word alphabet is derived from the first two letters of the Greek system, alpha and beta. The Greek system influenced a number of divergent alphabets, including Latin and Cyrillic. While Cyrillic maintained some of the Greek characters, the western alphabets, like the alphabet used in the British Isles and the United States today, developed to approximate the Greek characters. With the creation of a more flexible system of writing came the eventual regional standardization of language.

The importance of an alphabet to the standardization of language cannot be overstated. Alphabetic writing uses letters to represent sounds segments. By combining these sound segments, new words can be created. This makes for an incredibly adaptable language that allows for additions without becoming too vast to comprehend. In pictographic systems, the glyphs rarely change. Instead, they are mixed and matched to create new sounds, therefore new words, therefore new concepts. Ideographic symbols may have represented more complex concepts, such as death, but they could not be used to articulate the notion of death to the same degree that an alphabet could.

Alphabets ultimately increased the descriptive ability of language. While some scholars possibly could have relayed a concept of a merciful death through pictograms, but it could not have been articulated in the same way that it was later articulated by Socrates when he said “Death may be the greatest of all human blessings.” There is more meaning in those few words than any number of pictographic symbols because while symbols allow people to communicate via writing, they cannot completely articulate the intricate thoughts of the human mind. All the elements that go into the Socrates statement, the concept of life as pain, the mercy of death, and even the notion of blessings would be difficult to express through pictographs.

There are also theoretical concepts, such as non-existence, which cannot be expressed purely through symbols. There is no conceivable way to relay the ‘absence of an object’ using pictographic writing. The very presence of a symbol to represent an absence is paradoxical. Of course, ‘nothing’ might be represented by a blank space, but there would be no way to differentiate one blank space from another blank space. Our language has evolved to incorporate concepts beyond that which we see in the natural world. For instance, love is unquantifiable in natural phenomenon, yet it consumes a large portion of our existence.

As human civilization moves into the future, our knowledge of the theoretical is likely going to expand, and the flexibility of our language combined with the flexibility of our number system allows that theoretical knowledge to flourish. The Sumerians may have been philosophers and mystics, but they could not reach beyond a certain point in their society, because they did not have the means. While certain truths, such as the revolution of the Earth around the Sun, may have been deduced by even the earliest civilizations, those civilizations had no means of conveying those concepts to the masses. And if they did discover a way to share their knowledge, what they learned was likely suppressed by those whose power would have been compromised by such discoveries. But as society evolved, as language became standardized, the dissemination of such concepts became easier.

Eventually, the dissemination of knowledge became so vast, that more sophisticated means were required to release that knowledge. Eventually, science created the first truly mathematical language, known as binary code. Binary code consisted of ones and zeroes in a specific order. Depending on the order of these ones and zeroes, computers could create different programs, from games to accounting software. In the beginning, computers were a source of entertainment, a device used to play Zorg or other text-based role-playing games. As society evolved once again, the computer became a more complex machine. The ones and zeroes could be combined in infinite ways to create everything from 3D design software to virtual personal assistants. While mathematics instead of language seems to have played the larger role in the creation of computers, mathematics, from its roots in mnemonics, is a form of language. Carl Sagan called mathematics “the universal language.” Universal because astronomers suspect that first contact with an alien species will be numbers-based contact, such as a prime number sequence.

Human life and civilization has been forever altered by the evolution of writing. With the standardization of alphabets, there came the means to deciphering even languages foreign to our own. While some systems still use picture writing, such as the Chinese system of writing, they have also developed phonetic variations. Relatively speaking, writing has developed rather quickly, becoming prominent in the last five thousand years. Writing began as rudimentary symbols and figures carved in stone or drawn on cave walls, but soon evolved into complex picture writing systems. Those pictograms and ideograms, however, grew too complex to be viable to language development. Therefore, picture writing systems developed into phonetic writing systems, systems in which letters came to represent specific sounds. As society moves forward, as our culture spreads from the real world to the virtual world, language only has room to grow.

About the Creator

Mack Devlin

Writer, educator, and follower of Christ. Passionate about social justice. Living with a disability has taught me that knowledge is strength.

We are curators of emotions, explorers of the human psyche, and custodians of the narrative.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.