Faces of Terror: The SS Ourang Medan

What killed the crew of the Medan? Pirates? Chemical weapons? Fear itself?

The story of the SS Ourang Medan is one of the most popular tales of maritime terror ever told. Over the years it has spawned countless books, articles, and videos. It's even inspired a video game - The Dark Pictures Anthology: Man of Medan, released in 2019, which has brought the story renewed attention. So what is the Ourang Medan and why is its tale so horrifying?

THE MYSTERY

Most sources claim that the first mention of the Medan was made in 1948 in a three-part series of articles featured in De locomotief, a Dutch-Indonesian trade magazine. The articles tell the following story:

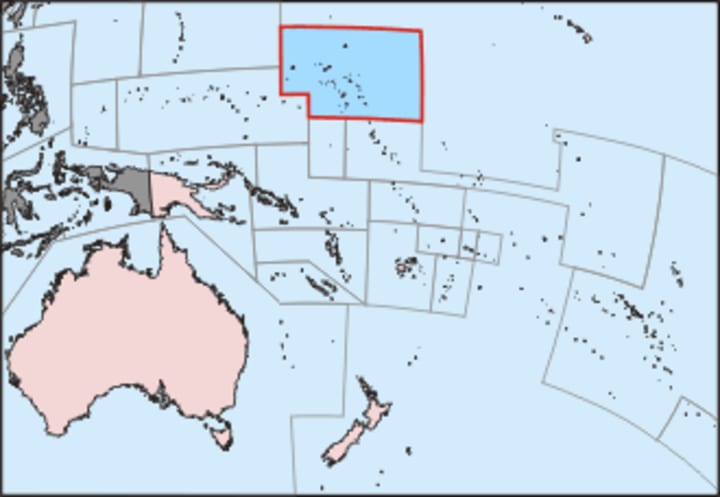

In June of 1947, the Dutch freighter ship Ourang Medan sent a series of ominous distress messages from a position of 400 nautical miles southeast of the Marshall Islands. These messages were received by the City of Baltimore and the Silver Star, both American ships.

The first Morse message said, "S.O.S. from Ourang Medan. **we float. All officers including the Captain, dead in chartroom and on the bridge. Probably whole of crew dead***." This was followed by indecipherable gibberish and then a final, chilling message: "I die."

The first to reach the Ourang Medan was the merchant ship Silver Star. They arrived to find a ship with no signs of damage and no signs of life above deck. They sent men aboard the Medan to find survivors and instead found the stuff of nightmares. The entire crew, each and every man, was dead. Bodies were scattered on the bridge, in the chartroom, and in the wheelhouse. The radio operator was found with his hand still on the telegraph. Each corpse's face was a frozen rictus of terror, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, as if screaming. Their arms were stretched out as if fending off an attack. The crew of the Silver Star could find no apparent cause for the deaths. By all appearances, it seemed as if the crew had simply died of fright.

They began to tow the Medan to port when thick smoke started to rise from the cargo hold. The Silver Star's crew had just enough time to cut the tow line before the Medan exploded and then quickly sank.

The articles also claim that there was a survivor of the Medan, an unnamed German man who washed ashore on Toangi atoll in the Marshall Islands and told his story to a missionary before dying. The missionary, Silvio Scherli of Trieste, Italy, then told the story to the author of the articles. The survivor supposedly claimed that the crew had been killed by fumes from broken containers holding illicit sulphuric acid.

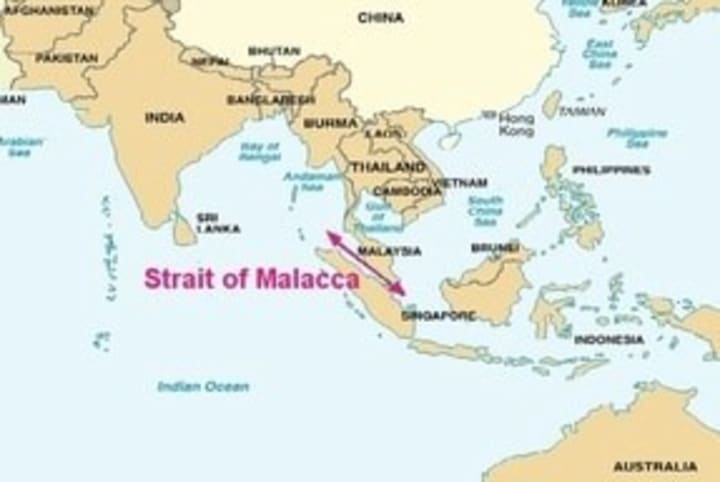

Over the years, other details and elements have been added to the story, such as the addition of a ship's dog who shared the crew's fate, the rescuing crew feeling the temperature drop dramatically while aboard the Medan, and the bodies decomposing at an accelerated rate. The date shifted to February 1948 and the location somehow shifted 4,000 miles west to the Strait of Malacca, in Indonesian waters.

While a fascinating story, the 1948 version doesn't appear to be the original one, as many sources claim. Estelle Hargraves (2015), editor of the Skittish Library, discovered newspapers from 1940 featuring accounts of the Medan - seven years before the De locomotief articles said the event took place. The earliest of these is the 21 November 1940 edition of the Yorkshire Evening Post and the 22 November 1940 edition of the Daily Mirror, both of which cite the Associated Press as their source.

Both articles tell the same story, one that is markedly different from what is found in most modern sources. They make no mention of the bodies looking terrified or reaching out. They only mention that the bodies had no visible wounds and that "Death seemed to have taken them by surprise at their posts." The articles describe the Medan as a steamship instead of a freighter and say that it was found southeast of the Solomon Islands instead of either the Marshall Islands or Straits of Malacca.

The SOS message is also completely different. According to these newspapers, the first message was: "SOS from the steamship Ourang Medan. Beg ships with shortwave wireless to get touch doctor. Urgent." The second message received said, "Probable second officer dead. Other members crew also killed. Disregard medical consultation. SOS urgent assistance warship." The telegraph operator then gave the Medan's position and sent one last message: "Crew has . . . "

The news articles claim that the story came directly from a merchant marine officer from the rescuing ship, which is not named. Hargraves points out that the information in the 1940 version comes from Trieste, Italy - the same place that Silvio Scherli (who supposedly heard a survivor's story in 1948) hails from.

She speculates that Scherli could be the source of the 1940s reports. It is unknown whether or not he made up the story entirely for the first reports (if he was, in fact, the source). Hargrave believes that he did make up those first stories and that he retold the story numerous times over the years, adding and embellishing details (like the state of the bodies) and completely changing others (like the date and location). Eventually, we ended up with something close to the story most often told today.

THE THEORIES

Assuming that the story wasn't a fictitious invention from the beginning, there are several possible theories to choose from that might explain what happened to the crew of the Medan. Some of them are more credible than others.

Some have theorized that the Medan was carrying a poorly secured cargo of illegal chemical agents that would have been banned by the 1925 Geneva Protocol. Proponents of this theory cite a 32-page German booklet published in 1954 by Otto Mielke entitled Das Totenschiff in der Südsee ("Death Ship in the South Sea"). The booklet mentions a cargo of "mixed, lethal" potassium cyanide and nitroglycerin.

Theorists claim that there was a market for illegal nerve gas and biological agents following World War II and the perfect way to move such illicit cargo was to hire an inconspicuous old steamer with a low-paid crew. They posit that the chemicals were improperly stored in containers that wouldn't draw attention to their contents. The containers could have leaked, asphyxiating or poisoning the crew. The chemicals could later have come into contact with seawater, resulting in the explosion that sank the ship.

Others have taken this theory even further, hypothesizing that the cargo was illegal nerve gas being smuggled specifically for the Japanese army.

From 1938-1945, Lt. Gen. Shiro Ishii, a microbiologist and army medical officer of the Imperial Japanese Army, headed what was known as Unit 731, operating out of Japanese-occupied Manchuria. Unit 731 was a secret unit tasked with finding a weapon - chemical, gas, or biological - that would win the war. They attempted to complete this task by experimenting on humans, committing some of Japan's most notorious war crimes.

These theorists claim that any mentions of the incident have been expunged from official records in a multi-national cover-up perpetrated by Japan, the Netherlands, China, Germany, the United States, and possibly others. Of course, these theories are dependent on the idea that the Medan was traveling the Strait of Malacca when she sank, which Hargraves' research disproves. (The question of why non-Axis countries would participate in this cover-up is never addressed.)

Vincent Gaddis, American author and the man who coined the phrase "Bermuda Triangle," has put forth the theory that the crew of the Medan succumbed to carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning. His theory is that a faulty boiler system released CO fumes that poisoned the crew. The malfunctioning system also, presumably, led to the explosion.

Some theorists point to possible hallucinations caused by CO poisoning as a reason for the terrified-looking bodies. CO poisoning is known to cause dizziness, nausea or vomiting, shortness of breath, confusion, blurred vision, loss of consciousness, and even death. Some sources say that hallucinations can occur, while others fail to mention them at all. Regardless, since it is now known that the original story made no mention of the crew looking scared, the notion of hallucinations can be dismissed entirely.

The question of hallucinations aside, the theory doesn't quite explain the entire crew's deaths. While it could account for the deaths of those who were below decks in enclosed spaces, those working the upper decks would have had plenty of fresh oxygen.

Some sources site the Strait of Malacca's long history with piracy as possible explanation. But, again, this doesn't quite fit. Even the earliest reports make sure to mention that the bodies found had no visible wounds. It's unlikely that a hostile force could invade the ship and kill everyone aboard without leaving so much as a bruise.

Again, this theory assumes the Strait of Malacca as the site of the incident and it's unclear how likely one would be to run into pirates off the Solomon Islands in 1940.

THE CONCLUSION

It's difficult to say which of these theories is the most likely since none of them fully explain the details of the story. It might be a moot point anyway since it doesn't appear as if the Medan existed at all.

Researchers have searched Lloyd's Shipping Registers, the records of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, Dutch shipping records, and various other sources without ever finding mention of the Medan. There doesn't seem to be any record at all anywhere of such a ship ever existing.

If it did exist, we may never know what happened to the SS Ourang Medan and her unfortunate crew unless the wreckage turns up. Until then, the Ourang Medan legend lives on.

* * *

Notes:

Header image does not show the actual Ourang Medan. Picture of the Dutch merchant steamship Straat Malakka in 1940. [From the Collection Database of the Australian War Memorial under ID #128097, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.]

This story was originally published on 11 Oct. 2019 on Medium. The version posted here has gone through some minor edits.

* * *

Sources:

Bainton, R. (1999, Sept.). Cargo of death. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20070205223141/http://www.neswa.org.au/Library/Ar ticles/A%20cargo%20of%20death.htm

Beyond Science Staff. (2017, Jul. 31). The Ourang Medan, the mystery of the deadliest ghost ship in history. Retrieved from https://www.beyondsciencetv.com/2017/07/31/the-ourang-medan-the-mystery-ofthe-deadliest-ghost-ship-in-history/

Federation of American Scientists. (2000, Apr. 16). Biological weapons program. Retrieved from https://fas.org/nuke/guide/japan/bw/

Hargraves, E. (2015, Dec. 29). The myth of the Ourang Medan ghost ship, 1940. Retrieved from http://skittishlibrary.co.uk/the-myth-of-the-ourang-medan-ghost-ship1940/

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2018, May 17). Carbon monoxide poisoning. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/carbon-monoxide/symptomscauses/syc-20370642

* * *

Like what you read? Don't forget to <3 and subscribe, or even tip!

About the Creator

B. Jessee

Appalachian writer & nerd. Writes about the strangest bits of history and science as well as science news.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.