Banabans Compensation Claims

Members of UK Parliament deciding the Compensation owed to the Banabans, July 1979

PART TWO

Excerpt of debate over the compensation claims for the Banabans (Ocean Island). Tabled in UK House of Commons in July 1979, a scathing report of the grievous wrongs and exploitation inflicted on the Banabans during seven-nine years of the mining era. After Judge Megarry's findings in the Banabans civil court case in the UK High Court, what is deemed as 'fair' compensation? As the future of the Banabans in handed over to the newly formed Kiribati Government.

House of Commons Official Report, Parliamentary Debates, (Hansard), Volume 950 No.120

BANABANS (COMPENSATION CLAIMS)

26 July 1979 vol 971 8.40 am

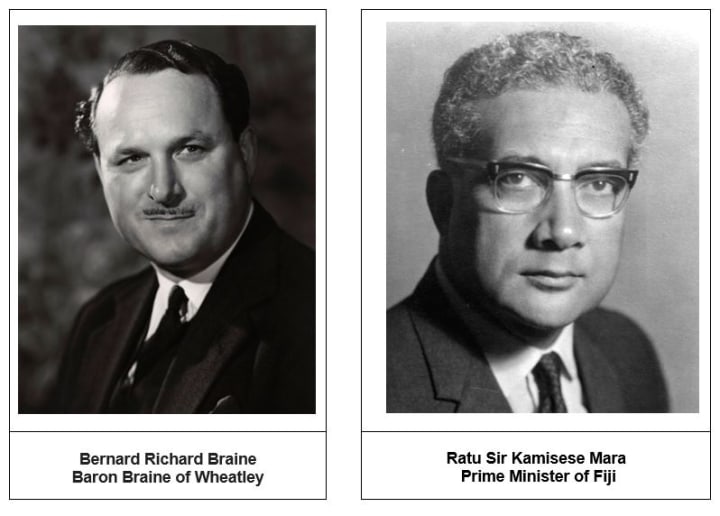

Sir Bernard Braine (Essex, South-East) [1]: I am grateful for the opportunity to raise a serious matter that has caused me and many other hon. Members from all parties deep concern over a long period, namely, the treatment accorded the Banaban community in the Pacific and the need to make amends.

On 12 June this House gave a Third Reading to the Kiribati Bill [2] and by so doing ruled that the Banabans were to be split between two sovereign jurisdictions, Fiji and the new Kiribati republic and that their original homeland was to go to Kiribati against their will.

Many of us on both sides of the House regarded the decision not to separate Banaba [3] from the Gilbert Islands colony—now Kiribati—as wrong, indeed as a final betrayal by the imperial power of its trust for a small, defenceless community. Many people who heard and read our debate wrote to me afterwards saying that our arguments were unanswerable—and so they were. Nonetheless, the Government threw their weight against us, and a majority in Parliament decided to ignore the Banaban plea for separation from Kiribati and agreed that on 12 July sovereignty should pass finally and irrevocably to the Kiribati republic.

Thus the political future of Ocean Island, or Banaba, is now solely a matter for the Kiribati Government and people. It remains for this House simply and sincerely to wish them well and to hope that the discussions that the new Government have offered to hold with Banaban representatives, under the chairmanship of that greatly respected statesman of the Pacific, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, Prime Minister of Fiji, will lead to a solution that the Banabans can be persuaded to accept.

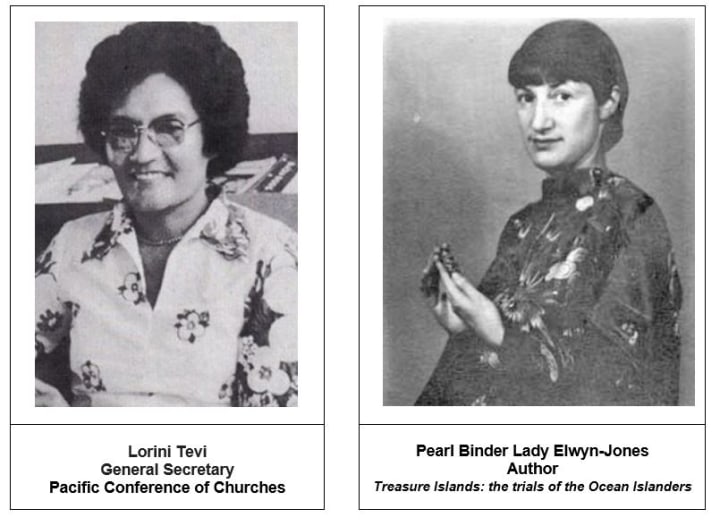

Earlier this month the Pacific Council of Churches met and deliberated on the dispute between Kiribati and the Banabans. The Government have been singularly deaf to what has been said on the subject in the Pacific, and my hon. friend the Minister might like to know that the council recommended, as its secretary, Mrs Lorini Tevi [4] stated, that Ocean Island remains a British colony until a solution was reached that was acceptable to both parties. Alas, that is no longer possible. We have hauled down the flag and have passed sceptre to others. We no longer have any say in the political shape of things to come in that part of the Pacific. In one respect, however, we retain a responsibility for the welfare of the Banaban people that the Government cannot shuffle off.

The Government still have a duty to discharge towards the people whom their predecessors have grievously wronged.

We still have to pay the ex gratis capital sum by way of compensation arising out of the High Court proceedings that the Banabans were forced to take against the British Government. We are under an obligation to provide the aid and technical assistance necessary to safeguard the economic future of the Banabans now split by our actions between two island homes.

My hon. friend may be inclined to argue that our financial obligations towards the Banabans must be viewed in the context of our general aid programme. He may add that whatever help we give must also be affected by the stringent economic measures at present in force. In case there is any suggestion that the Banaban case is not unique, I think it is right that the House should know and that our official record should reflect the circumstances that give rise to the special and morally compelling obligation of this country towards the Banabans. That is the purpose of my raising the matter today.

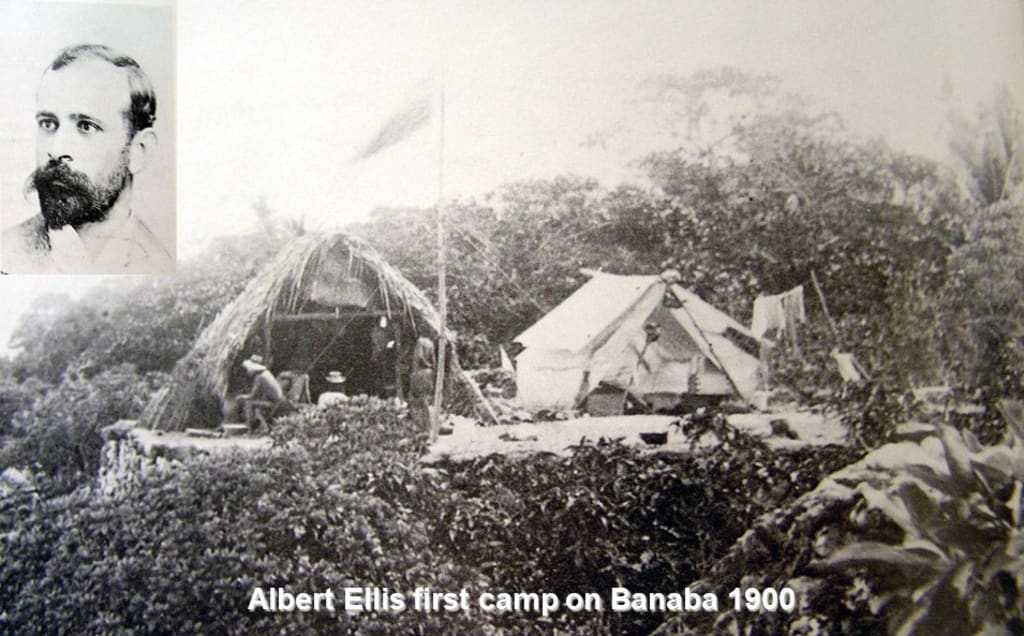

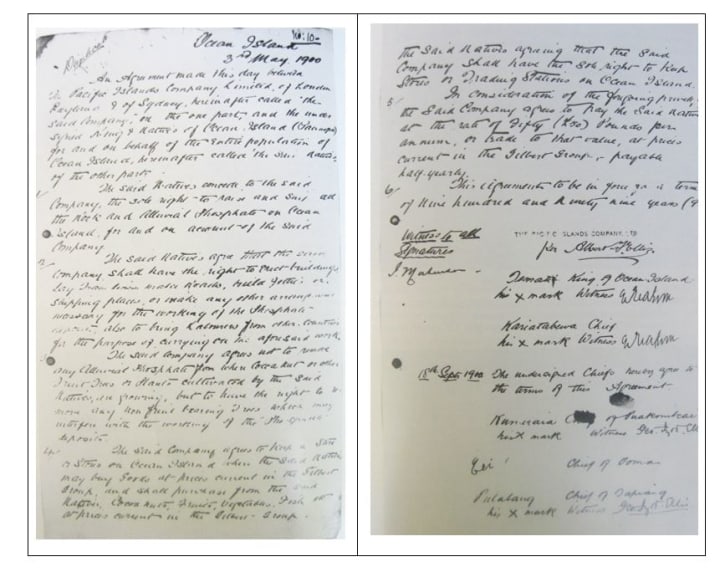

In May 1900 the representative of a British company, Mr Albert Ellis, perpetrated upon the Banabans a sordid confidence trick. He fooled them into signing away the right to exploit their phosphate wealth for 999 years in exchange for £50 per annum, payable either in cash or in company goods, at the company's option. It may be said that much-legalised robbery of this nature took place at that time and that later the Colonial Office did something to mitigate its worst aspects. It could hardly have done less.

Suffice it to record of this distasteful episode in our mercantile and colonial past that the founder of one of our largest public companies, Unilever, was a director and major shareholder of the company that so pitilessly exploited the Banabans. Pearl Binder [5] whom most of us in this House know by another distinguished name, tells us in her moving book "Treasure Islands": In 1920 when Lord Leverhulme's £100 million company was in serious financial difficulties the sale of his major holdings in the Pacific Phosphate Company's shares to the BPC, and the lavish compensation to the directors, helped to save Leverhulme from bankruptcy. The price received was very many times the original investment and was only agreed after protracted and bitter negotiations during and after the Versailles conference. Criticism and acrimonious complaints about the methods of the company had been continuous throughout its life. No doubt my hon. friend will tell me that he cannot be responsible for the unethical behaviour of three-quarters of a century ago. I do not disagree. But I believe it only right to record that one of our most prestigious public companies may owe its very existence to the rape of Banaba. I must also record with regret that the company in question chose to turn down an appeal for financial assistance which I made to it on behalf of the Banabans.

However, as the right hon. Member for Orkney and Shetland (Mr Grimond) pointed out on the Second Reading of the Kiribati Bill, the exploitation of the Banabans is remarkable for the fact that since 1920 the exploiters have not been great private corporations but the three Governments of the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, acting in concert for the benefit of their own national interests. Whatever earlier wrongs were committed by private enterprise, these pale into insignificance against those perpetrated by a public corporation and by Government officials who knew what they were doing.

I stress at this point that, although the three nations represented by the British Phosphate Commissioners benefited from the exploitation of Banaban phosphates, Britain and Britain alone was the responsible, sovereign administering Power. I should like my hon. Friend to take special note of this fact for reasons which I shall give later.

What is it that puts the treatment of the Banaban people in a class of iniquity of its very own? I shall describe briefly, more briefly than I would wish, just two episodes.

By the time the British Phosphate Commission came into being in 1920, about 22½ per cent. of the phosphate-bearing land on Ocean Island, or Banaba had been leased for excavation. The Banabans had already shown considerable reluctance to part with any more, but within three years the commissioners were demanding nearly 10 per cent. of the available phosphate land for future mining. The Banabans refused. Where, they asked, would their children live? If, however, more land was leased, they would require not £150 per acre as suggested, but £5,000 per acre. As the proceeds of mining amounted to some £40,000 per acre, the Western Pacific high commissioner commented at the time that the Banaban demand did not appear to him to be unreasonable—not that right or reason have any place in this story.

Britain's residential commissioner in Ocean Island, the effective governor at the time, pressed the commissioners' requirements unscrupulously during 1927 and 1928. He offered £150 per acre for the Banabans' land, an amount equivalent to a penny farthing in old pence per ton of phosphate, together with a royalty of 10½d. per ton. The Banabans made it plain that they did not wish to sell but asked the resident commissioner why 10½d. was the limit that the British Phosphate Commission could pay. He told them that competition in Australia and elsewhere made it necessary for the British Phosphate Commissioners to sell at the lowest price possible. Increased royalties would make them uncompetitive, and that would be the end of the commission and would therefore mean a sentence of death on the Banabans, who were by then dependent on the industry.

It was, of course, a complete lie. At the time the Banabans were being told that a total payment of anything more than 11¾d. per ton would render the British Phosphate Commissioners uncompetitive, Banaban phosphates were being sold to Australia at 12s. 6d. per ton cheaper than the nearest equivalent source. In moral terms, this amounted to fraud perpetrated with the assistance of blackmail. "If you do not sell on my terms," the British resident commissioner had told the Banabans," your land will be seized for the Empire at any old price "—to use his elegant words—" and your homes destroyed". Although the Banabans still refused, their land was compulsorily purchased in 1928 at £150 per acre and with a royalty per ton to be prescribed by the resident commissioner himself.

I now turn to the second episode which makes our moral obligation towards this tiny community uniquely imperative. The Second World War and Britain's abandonment of their homeland to the Japanese saw most Banabans exiled for forced labour; the rest were brutally murdered.

After the war, the surviving Banabans were shipped by the British to Rabi, an island in the Fiji group, 1,400 miles to the south—bought, incidentally, with their own money. The colonial Government regarded the opportunity of removing the Banabans from Ocean Island as unique and urged the British Phosphate Commissioners that shipping difficulties should not be permitted to frustrate a project which they had been striving to achieve for decades.

A return to Ocean Island, the Banabans were told, was impossible; everything there was destroyed; they would have to live there in tents. They were offered a free choice: they could go to Rabi or fend for themselves in the Gilbert Islands, as they had done during the Japanese occupation. Given this invidious choice, the Banabans went to Rabi. There they were dumped in the hurricane season to fend for themselves with a few months' provisions and some tents. In short, no more permanent accommodation existed on Rabi than they would have found on Ocean Island.

Yet all this, too, was based on a lie. At the very moment that the Banabans were being told this, unbeknown to them the British Phosphate Commissioners, with the active co-operation of the colonial authority, were busy recruiting labour elsewhere to resume phosphate mining on Ocean Island and were preparing permanent accommodation and social services for the newcomers which would have been most welcome for at least part of the indigenous Banaban community.

The coup de grace was administered in 1947 when the unfortunate Banabans were persuaded both to remain on Rabi and to sign away on fixed and immutable terms 58 per cent. of the total phosphate land which had existed at the outset and virtually all that remained.

To describe this infamous treatment of a defenceless people, I can do no better than quote briefly from the historic judgment of the Vice-Chancellor, Sir Robert Megarry [6], at the end of November 1976. Ministers of both Governments should hang their heads in shame at what he said: The other failure of government to which I shall refer was the gravest in its consequences to the Banabans. That was the absence of any advice to the Banabans, or encouragement to get advice when they were embarking on the 1947 negotiations. The Banabans had suffered grievous hardships under the Japanese during the war: they had been uprooted from their homes on Ocean Island and had no immediate prospects of returning even to see what state that island was in; they had been less than a year and a half on Rabi, an unknown island in a different colony with a markedly different climate; they had had all the problems of living in temporary or makeshift accommodation, like so many others after the war; and many of them had been ill. In those circumstances, they were about to embark upon negotiations for by far the largest disposition of phosphate land that they had ever made, one which would take nearly all the workable phosphate left on Ocean Island, and consume well over two-fifths of the entire island.

The learned judge concluded from this: All these facts must have been known, and well known, to the High Commissioner and to Major Holland [7], whom the High Commissioner had appointed to look after the Banabans. In those circumstances, I do not see how the omission to encourage the Banabans to get proper advice and assistance and to make haste slowly, and the prohibiting of Major Holland from helping the Banabans can possibly be called good government or the proper discharge of the duties of trusteeship in the higher sense. The Vice-Chancellor was referring here to an instruction in writing from the high commissioner to the Banaban adviser, Major Holland, not to advise the Banabans, who were paying his salary. It is one of the worst examples that I can recall of a breach of duty by the administrators of a subject people. The Banabans were again pushed into signing what they did not fully comprehend. As a consequence, they were totally unaware of this expropriation of their phosphate resources until they hired professional advisers in Australia in 1965, some 18 years later.

As any payments to the Banabans will be in present-day currency, I am sure that my hon. friend will agree that it is only fair to take inflation into account. The £62 million benefit obtained by Britain has a current purchasing power of £103 million. The £17 million benefit obtained by Australia and New Zealand over the years has a current purchasing power of £69 million. Thus we arrive at a total, in today's terms, of £172 million which was obtained from the Banabans by a shameful combination of bullying, coercion and chicanery. My hon. friend need not look at me: the figures are derived in part from answers received from Ministers in this House.

These are the very special circumstances that make our obligations towards the Banabans, whether within Fiji or Kiribati, unique and compelling.

How do the present Government propose to compensate the Banabans? We are in the process of trying to work this out. With all the assistance that our partners in this sorry business—Australia and New Zealand—can be persuaded to give, how much will the Banabans receive now that the phosphate is exhausted and their original homeland almost totally destroyed? I shall give the figures and, to be more than fair, I shall give the sterling equivalent of the Australian offers or awards at the exchange rate applicable at the time that they were made: first, in exchange for calling off all legal action against the Crown, £6.25 million; secondly, a sum of interest on this sum which has so far been agreed at £937,500: thirdly, in settlement of the Banabans' case against the commissioners, £780,000: fourthly, as a grant of development aid from the ODA, £1 million. The grand total is less than £9 million. Seen in the context of the £172 million which Banaban phosphates contributed for the benefit of others, such a sum is pathetically inadequate. It must be increased substantially if we are to emerge from this shameful episode in our history with any credit at all.

I must tell the House that as chairman of the justice for the Banabans campaign and at the invitation of the Banaban leaders, I have taken part in discussions with the Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, my hon. friend the Member for Blackpool, South (Mr Blaker) [8]. Those discussions have been aimed at negotiating the transfer of all the sums that I have listed, with the exception of the British Phosphate Commissioners' payment of £780,000 which has been made already. I am aware that my hon. friend will shortly be conferring with his opposite numbers in the Australian and New Zealand Governments about the transfer of money already offered. The Banabans, with the help of their able and experienced economic adviser, Philip Shrapnel and Company, of Sydney [9], have proposed the investment of the money in a Banaban fund to be audited, we hope, by the Auditor-General of Fiji. That is going smoothly. I am confident that my hon. friend is fully seized of these matters and will do his best to move things along.

I must, however, draw the attention of the House to an aspect of the matter that causes me and my fellow trustees grave disquiet. I am still speaking within the context of the totally inadequate sums which have been offered. I am sorry to tell the House that the payment to the Banabans of a sum of interest amounting to about £300,000 is still being disputed. I have already made my personal views of this wholly unexpected piece of meanness plain to my hon. friend.

The House should be aware of the details as the sum in question arises out of a statement—I would say a pledge—made to this House by the former Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, the right hon. Member for Plymouth, Devonport (Dr Owen) [10]. On 27 May 1977, the right hon. gentleman told the House that the then Government were offering the Banabans 10 million Australian dollars, that is, £6.25 million, on certain conditions, the principal one being that they would not appeal their case against the Crown. It was a matter of "You call off your appeal against the Crown and we will offer an ex-gratis payment of 10 million Australian dollars or £6.25 million". In answer to a supplementary question by my right hon. friend the then Member for Knutsford, Mr John Davies, [11] the Foreign Secretary said: We estimate that the 10 million Australian dollars, invested now, would accumulate to 12 million dollars by the end of 1979 when phosphates run out. This sum would give the benefits of unearned income of about 350 dollars per capita."—(Official Report, 27 May 1977; Vol. 932, c. 1761.)

On 30 November, Lord Goronwy-Roberts [12], the Minister of State, who was handling the matter in the other place, wrote to the Banabans to say that the notional interest on the 10 million Australian dollars amounted by then to 1.5 million Australian dollars. The noble Lord felt that the Australian and New Zealand Governments would agree to this being paid if he received an early indication that the offer as a whole would be accepted by the Banabans.

The House will recall that at that time the Banabans had just been told that they would be forced against their will into the new Kiribati State. They were not prepared to accept this, as was their right. They were determined to fight the political battle to the very end. They had no wish to haggle over money while the constitutional question closest to their hearts remained at issue.

I can understand the then Government's wish to persuade the Banaban leaders to accept the money. Had they done so, I have no doubt that it would have been widely suggested that money was more important to the Banabans than self-determination. Innuendoes of that kind, as many of my hon. friends know, have been made more than once. Indeed, in order to attract the Banabans into a discussion on financial matters, Lord Goronwy-Roberts added to the lure of interest payments the promise of development aid amounting to £1 million and a resources survey of Banaba. That was very attractive.

But, as the carrot did not work, the stick was then used. If the Banabans refused to talk about the money while the political battle raged, interest accruing on the capital sum would not be paid to them after 31 December 1978. That is almost without precedent in negotiations of this kind. I have told my hon. friend that I could see no justification whatever for punishing the Banabans for not meeting the Government's wishes. I have made plain that if the interest accumulating on this capital sum continued to the end of phosphate mining, as the former Secretary of State indicated in the House it should, they ought to receive not only the 1.5 million Australian dollars which had accumulated by 30 November but every single cent that accrues from that date to the moment the capital sum itself is made over.

I am glad to see an increasing number of right hon. and hon. Members in the House as I am confident that anything less will be regarded by them as a mean and vindictive act and would be totally unacceptable either to them or to the wider public outside. Our national reputation has been besmirched enough already by years of mistreatment of these people without its being besmirched further by this final dishonourable act.

I have confidence that my hon. friend has grasped this point. He has, after all, come to office only recently. He can be acquitted of any responsibility for the misdeeds perpetrated earlier. I trust that he will put forcefully to the Australian and New Zealand Governments what I have said. I hope that he will find, as I have suggested to him, that his information that our partners in the British Phosphate Commissioners are adamant in withholding interest after 31 December is not accurate.

Up till now, the British Government have suggested to me that the reason for this lies in the attitude of the Australian and New Zealand Governments. I can say with some authority—I have received information from down under—that in the case at least of New Zealand that is utterly untrue. As I shall be visiting New Zealand next week, I shall raise the matter with Ministers there.

So the British Government have no right to shelter behind allegations that the Australian and New Zealand Governments have been dragging their feet. However, wherever the truth lies, it is neither morally right nor economically sound to apply any terminal date for the payment of interest before the final handing over of the capital sum. If Australia and New Zealand refuse to accept that, I know that the House will expect the Government to make up any shortfall, and we should like some undertaking from the Minister about that.

Most of the paltry £9 million which is on offer arises out of an action brought on the advice of one of our most distinguished lawyers, Lord Elwyn-Jones [13], against the Attorney-General of the United Kingdom Government. The Australian and New Zealand Governments are to be commended for their willingness to contribute the larger part of an ex gratia payment in respect of a bill which strictly speaking is payable by the United Kingdom Government alone.

Indeed, when I visited the Pacific in 1965 and talked to Ministers and officials of the Australian and New Zealand Governments at that time, I was made fully aware that they recognised the great benefits which their farmers had received over many years from Banaban phosphates. They told me then, and others have told me since, that, irrespective of the case against the British Phosphate Commission, they were prepared to contribute generously to the Banabans in direct bilateral development aid. I trust that this is still the position.

My final words are these—(Interruption)

The House has been very patient and I am grateful for the moral support that it is giving me on this sad issue. It seems to be hoped in official circles that our debt to the Banaban people can be discharged by the payment of between £2 million and £3 million, most of which comes not from the taxpayer but from the reserve fund of the British Phosphate Commissioners, who have been exploiting Banaban and other Pacific island phosphates for nearly 60 years.

The officials of the Treasury and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office may consider this good housekeeping—perhaps it is when we consider how successive Governments have squandered our own national substance—but in this context, they must be told that it would be nothing less than a moral outrage that our contribution towards the future welfare of the Banaban people in their two island homes should rest there. I am making a plea for Her Majesty's Government in this final act of reparation—for that is what it should be—to err on the side of generosity. There is no other way in which to make amends.

9.4 a.m.

The Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office (Mr Peter Blaker) If I have the leave of the House to speak for a second time in this debate, I shall do my best to reply to my hon. friend the Member for Essex, South-East (Sir B. Braine). I hope he will forgive me if I am brief because I know that many other hon. Members wish to raise topics in this debate.

I will not go over the constitutional ground, because my hon. friend and I have tilled that pretty well in recent weeks. I do not accept his interpretation of opinion in the Pacific about this matter, having recently returned from there myself. I should say that on the financial claims, which are the real subject of this debate, I do not accept much of my hon. friend's extravagant language.

Four offers were made to the Banabans by the British, Australian and New Zealand Governments. First, an offer of 1.25 million Australian dollars was made by the British Phosphate Commission. That has been accepted by the Banabans. Second, an offer was made in May 1977 of a fund of 10 million Australian dollars to be provided out of the British Phosphate Commission's resources which would provide an income on a continuing basis for the Banabans as a whole. Third, an offer was made of £1 million for development aid for Rambi. Fourth, there is an offer of a resources survey on Ocean Island to see what use can be made of it. That offer has been accepted.

I regret that there has been considerable delay in the Banabans accepting some of those offers. I am glad, however, that in recent talks the Banabans have agreed to accept the offers, subject to legal formalities. We now hope to go ahead rapidly.

The main point made by my hon. friend was about interest. I do not accept his interpretation of the statement made by the right hon. Member for Plymouth, Devonport (Dr Owen) in 1977. I do not believe that he implied that interest would be paid. The right hon. Gentleman made his statement about interest on the assumption that the offer would be accepted rapidly by the Banabans. He made a calculation of the interest if it was accumulated until the end of 1979 when the phosphate mining will cease.

Nevertheless, an offer was subsequently made by the Australian, New Zealand and British Governments to pay interest up to the end of 1978. It was made clear before the end of 1978 that interest would not be paid after that date if the offer was not then taken up. I believe that the reason why that terminal date was set was that the three Governments, not least the Australian and New Zealand governments were becoming distressed about the long delay in taking up the offer.

Sir Bernard Braine: The Minister must be more specific. My information is that the New Zealand Government, and by inference the Australian Government, were prepared to pay interest up to the end of March. There is a big difference in that. Is my hon. friend saying that that is not so?

Mr Blaker: I have already taken up the question of paying interest after December 1978 at the highest level with the Australian and New Zealand Governments. I am anxious to help my hon. friend. I suggest that we should proceed as fast as possible to complete the formalities for the acceptance of the offer of 10 million Australian dollars. That will ease my task in persuading the Australian and New Zealand Governments to continue to pay interest to the latest possible date.

Sir Bernard Braine: My hon. friend cannot get away with this. He has not answered the question—

Mr Speaker: Order. The Minister has not given way.

Mr Blaker: My hon. friend does not correctly interpret the New Zealand and Australian position. I have talked at the highest level with those Governments recently. It will not be easy to persuade them to do what my hon. friend wants them to do. In my hon. friend's interest and that of the Banabans, I urge him to persuade the Banabans to accept the offer and the legal formalities as soon as possible. That will provide me with the best opportunity of persuading the New Zealand and Australian Governments to pay interest up to the latest possible date.

Question put and agreed to.

Bill accordingly read a Second time and committed to a Committee of the whole House; immediately considered in Committee, pursuant to the Order of the House this day; reported, without amendment.

Motion made, and Question, That the Bill be now read the Third time, put forthwith pursuant to Standing Order No. 93 (Consolidated Fund Bills), and agreed to.

Bill accordingly read the Third time and passed.

The Banabans would hold out for four years before finally accepting the 10 million offer.

_____________________________

- Bernard Richard Braine, Baron Braine of Wheatley, Privy Council of United Kingdom (PC), from 24 June 1914 to5 January 2000. He was a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom, a Member of Parliament (MP) for 42 years, from 1950 to 1992. Wikipedia.

- Kiribati Bill [H.L.] Hansard 22 March 1979 vol 399 cc1299-3011 moved for the third time by Lord GORONWY-ROBERTS and Moved, Moved, That the Bill be now read 3a.—(Lord Goronwy-Roberts.)

- The Banabans took their quest for Independence to United Nations to no avail. Britain decided to allow the newly forming Kiribati government. They would not grant the Banabans request for independence with the hope of remining Banaba in the future.

- Mrs Lorini Tevi, a Fijian and the first woman to be the General Secretary of the Pacific Conference of Churches (PCC) between 1970 - 1980, was recognised for her proactive advocacy role in the political decolonisation of the Pacific Islands.

- Pearl Binder, Lady Elwyn-Jones 28 June 1904 – 25 January 1990, was a British writer and author of "Treasure Island: the trials fo the Ocean Islander (1977) Wikipedia

- Sir Robert Edgar Megarry, 1 June 1910 – 11 October 2006) was an eminent British lawyer and judge. He served as Vice-Chancellor of the Chancery Division from 1976 to 1981. He sat in the case the Bananabans UK Civil Court Cast - Tito v Waddell (No 2), brought by the former residents of Banaba Island, Gilbert and Ellice Islands, whose island was all but destroyed by phosphate mining. He took the court on a 3-week trip to the south Pacific, to visit the island. After sitting for 206 days, Megarry delivered a judgment containing 100,000 words. He asked the Crown to do its duty to the islanders, but found that he was unable to require it to do anything. Wikipedia

- Major F.G.L. Holland, O.B.E., G.M Banaban Adviser on Rabi from 1946 to 1949.

- Peter Allan Renshaw Blaker, Baron Blaker, KCMG, PC, 4 October 1922 – 5 July 2009) was a British Conservative politician. Wikipedia

- The firm, Philip Shrapnel and Co. Pty Ltd were economic advisers for the Nauru Government and instrumental in the Nauruans receiving greatly increased phosphate royalty payment. One of the principals, Ken Walker would go on to handle the Banabans economic affairs.

- David Anthony Llewellyn Owen, Baron Owen, CH, PC, FRCP, born 2 July 1938. A British politician and physician who served as Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs as a Labour Party MP. Wikipedia

- John Emerson Davies, MBE, 8 January 1916 – 4 July 1979. A British businessman who served as the first Secretary of State for Trade and Industry. Wikipedia.

- Goronwy Owen Goronwy-Roberts, Baron Goronwy-Roberts, FRSA PC, 20 September 1913 – 23 July 1981, was a Welsh Labour Member of Parliament. Wikipedia.

- Lord Elwyn-Jones, Baron Elwyn-Jones, CH, PC, 24 October 1909 – 4 December 1989, known as Elwyn Jones, a Welsh barrister and Labour politician.

_____________________________

Get the Book!

Read more about the epic history of Banaba (Ocean Island) and the Banaban people (the Forgotten People of the Pacific) as they seek justice to save their island, their culture, their future. Te Rii ni Banaba- Backbone of Banaba, by Raobeia Ken Sigrah and Stacey King, available on Amazon here

First published: Hansard, Volume 950 No.120

Published online: Come Meet the Banabans 'Banaban History'

About the Creator

Stacey King

Stacey King, a published Australian author and historian. Her writing focuses on her mission to build global awareness of the plight of the indigenous Banaban people and her achievements as a businesswoman, entrepreneur and philanthropist.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.