Amazing Colorized Photos of Mata Hari Bring the Spy Vividly to Life

Artist Olga Shirnina’s artful colorizations are breathtaking

In the early morning hours of October 15, 1917, the world-famous woman known as Mata Hari was executed by a French firing squad, having been tried and convicted of espionage. There is much speculation among scholars as to whether or not she was guilty. Here, accompanied by vintage photos beautifully colorized by Russian artist Olga Shirnina (who works under the name of Klimbim) is her story.

Margaretha Geertruida Zelle (1876–1917) was born in in Leeuwarden, Netherlands, to Adam Zelle and his first wife Antje van der Meulen. She was the eldest of four children.

The Zelles were a well-to-do merchant-class family and Margaretha had a privileged childhood. But her fortune took a downturn when she was thirteen years old. Her father went bankrupt and her parents divorced. Two years later, her mother died and her family fell apart.

Although her father remarried in 1893, Margaretha chose to live away from home, first with her godfather in Sneek and then with her uncle in The Hague. She had studied for a time to be a kindergarten teacher, but left the program at age sixteen when she was found in a compromising position with her fifty-one-year-old principal.

“I was not content at home. . . I wanted to live like a colorful butterfly in the sun.”

― Mata Hari

When eighteen-year-old Zelle saw a newspaper ad for a wife placed by Dutch Colonial Army Captain Rudolf MacLeod, she saw her chance to escape the mundane. After marriage, MacLeod planned to return to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) with his bride.

Although MacLeod was twenty years her senior, Zelle answered the advertisement, and she and MacLeod were married on July 11, 1895, in Amsterdam.

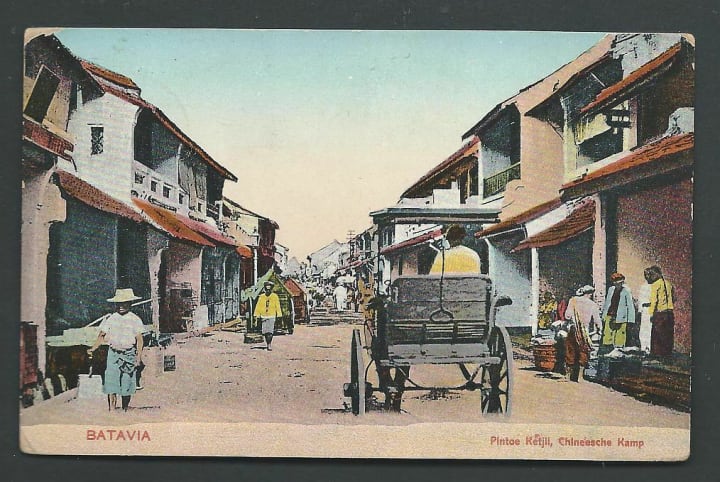

The couple settled on the island of Java and had two children: Norman-John and Louise Jeanne. Unfortunately, the marriage was not what the young woman had envisioned. MacLeod, an alcoholic, beat his wife and openly kept a njai, the Dutch East Indian equivalent of a live-in concubine.

Zelle left her husband briefly to move in with another officer, but MacLeod persuaded her to return. She immersed herself in Indonesian culture and joined a local dance company. She adopted the stage name of Mata Hari which in the Malay language means “sun” or “eye of the day.”

In 1899, both the MacLeod children became seriously ill and Norman-John died. The family put forth the story that a servant had poisoned them, but it’s more probable that their illness was an adverse reaction to treatment for syphilis, which they had contracted from their parents.

When the family returned to the Netherlands in 1902, Zelle and MacLeod officially separated. MacLeod did not pay child support and refused to return Louise after a scheduled visit. Without the resources to fight for custody, Zelle moved to Paris in 1903 leaving her daughter behind.

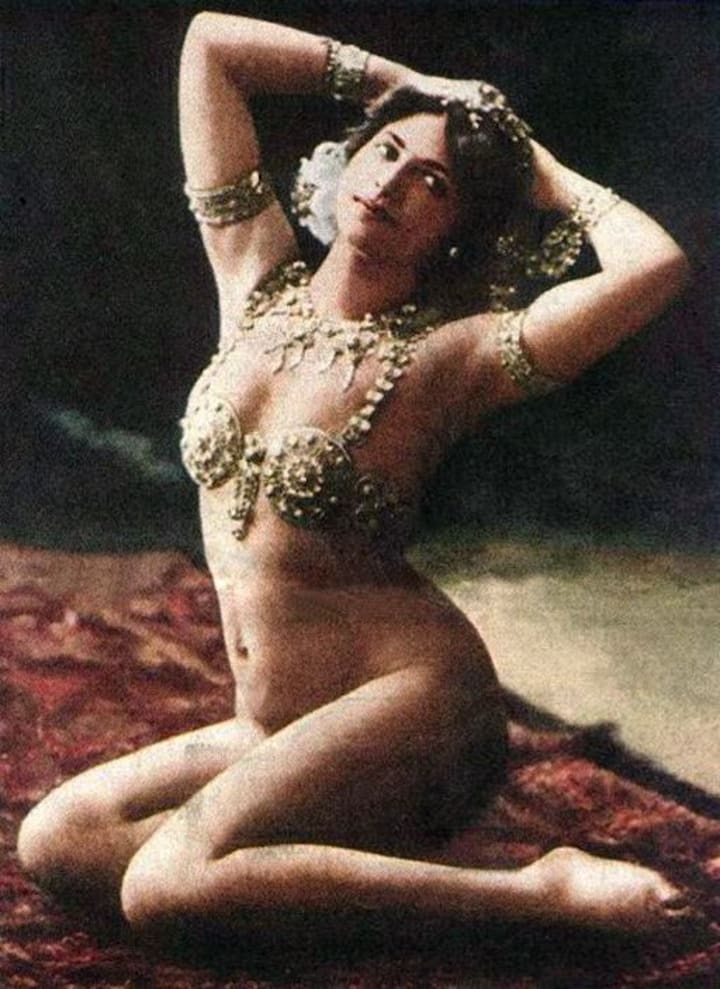

Zelle had a series of jobs in Paris including an artist’s model and a circus performer, but it was as exotic dancer Mata Hari that her career really took off. Her act at the Musée Guimet which opened on March 13, 1905, was a sensation. She posed as a Hindu Javanese princess who had been raised to perform ceremonial dances since birth. This sort of fictional origin story was common among performers of the era. (She had at least learned to dance in Java.)

Mata Hari’s performances were sultry and suggestive, incorporating a gradual striptease that left little to the imagination. She sometimes removed all but her jeweled breastplate and bracelets. (She never appeared bare-breasted, reportedly because she was self-conscious about the size of her breasts.) Her enthusiastic and appreciative audiences did not seem to mind.

“(She was) so feline, extremely feminine, majestically tragic, the thousand curves and movements of her body trembling in a thousand rhythms.” — contemporary review of Mata Hari’s performance in a Paris newspaper

Before long, Zelle became the mistress of the museum’s wealthy founder Lyon industrialist Émile Étienne Guimet. She tried unsuccessfully to regain custody of her daughter. Her ex-husband produced photographs of her in her performance attire (or lack thereof) to convince the court that she was an unfit mother.

The popularity of Mata Hari’s act led to the emergence of imitators. Her critics eventually turned on her, saying that her act was merely cheap sensationalism rather than art.

When World War I began in 1914, Zelle was free to cross borders because The Netherlands was a neutral country. She had numerous lovers among the military and was not particular as to their nationality.

By 1915, Zelle was pushing forty and no longer in high demand as a dancer. She performed for the last time in March of that year, but her liaisons with wealthy and powerful men continued to fund her opulent and expensive lifestyle.

Mata Hari’s fame had always been dependent upon her unbridled sexuality, but as conditions worsened across Europe, the public began to view her in a more critical light.

They had once considered her an artist, but now she seemed to be only a licentious woman of questionable loyalties. Since she was no longer a dancer and approaching middle age, people wondered if she was supplementing her income as a spy.

In the summer of 1916, one of Zelle’s lovers, a Russian pilot fighting for France by the name of Captain Vadim Maslov was shot down. When she asked permission to visit him, the Deuxième Bureau agents told her that she would only be allowed to do so if she agreed to spy for France. They offered her one million francs to seduce Germany’s Crown Prince Wilhelm to obtain military secrets.

In November of 1916, Zelle left Spain and was stopped when her ship reached Falmouth. She was arrested and brought to London where she was interrogated by Sir Basil Thomson, assistant commissioner at New Scotland Yard in charge of counter-espionage. Zelle admitted to Thomson that she was spying for France and she was released.

In late 1916, Zelle met with the German military attaché, Major Arnold Kalle, in Madrid. She asked him if he could arrange a meeting with the Crown Prince. It was later alleged that she agreed to act as a double agent for Germany in exchange for money. Whether she intended to spy for Germany or just wanted the money is uncertain.

Before long, it became clear to the Germans that they had made a bad bargain: Mata Hari didn’t have anything useful to report on the French. The French, in turn, got very little useful information on the Germans. In January 1917, the Germans transmitted a radio message to Berlin that was intercepted by the French.

The message hinted that an agent who closely matched the description of Mata Hari had provided Germany with useful information. Since the Germans used a code they knew the French had already broken; it seems clear that they intended to get her off their hands by getting the French to arrest her for espionage. The plan worked.

Zelle was arrested in Paris on February 13, 1917. She was tried on the charge of spying for Germany on July 24. The French made the doubtful claim that her activities led to the deaths of at least 50,000 soldiers.

Although she proclaimed her innocence, she was found guilty and sentenced to death by firing squad.

The woman known as Mata Hari went to her death early on October 15, 1917. Eyewitness Henry Wales, a British journalist, reported that Zelle was unbound and refused a blindfold. Just before a dozen French soldiers responded to the command to fire, she blew them a kiss.

Wales wrote that, after the shots rang out, she maintained eye contact with her executioners as she sunk to her knees and then collapsed backward. An officer approached her body and fired a single shot into her skull to ensure her demise. Zelle died as she lived, unapologetic, defiant, and with her head held high.

About the Creator

Denise Shelton

Denise Shelton writes on a variety of topics and in several different genres. Frequent subjects include history, politics, and opinion. She gleefully writes poetry The New Yorker wouldn't dare publish.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.