We, humans, are the yardstick, and it is set low

For a few weeks, many developers are allowed to play around with the currently most powerful tool for artificial intelligence. The results are impressive — but also cast a rather poor light on us humans.

“The word information has a special meaning in this theory, which must not be confused with its normal use. In particular, information must not be confused with meaning.”

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver in “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” (1949)

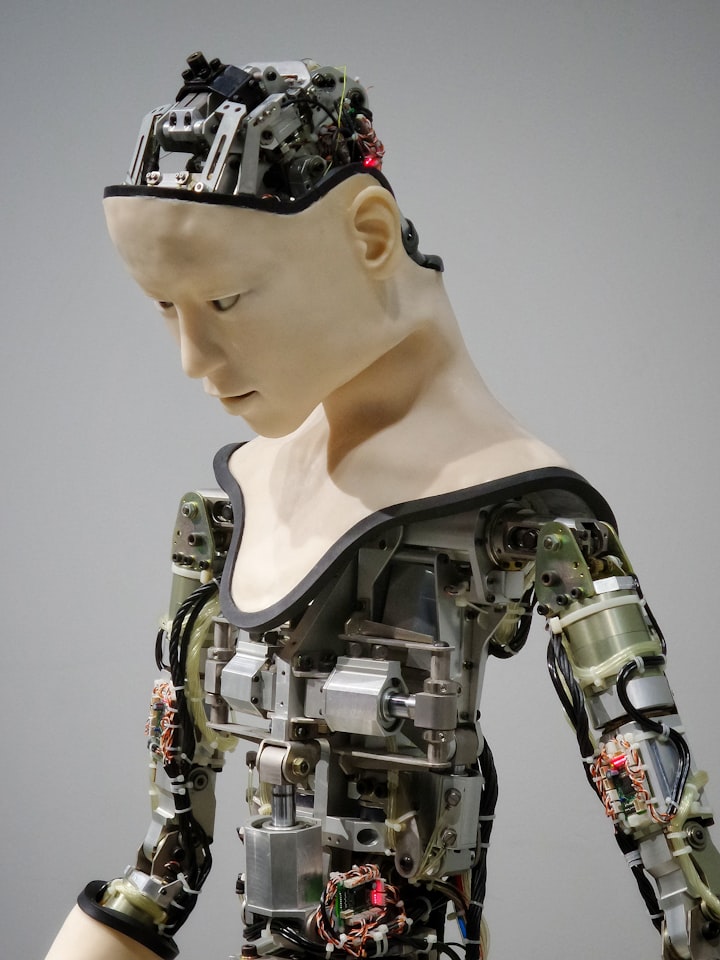

In a way, a very disturbing manifestation of what is commonly called “artificial intelligence” (AI) is this little robot. It has friendly, rectangular blinking eyes and looks a bit like a tiny Dyson vacuum cleaner.

If you ask him “Which actress is killed in the opening scene of the movie ‘Scream’,” he answers correctly: “Drew Barrymore. When asked what existentialism is, he replies, “Existentialism is a philosophy that stresses the freedom of the individual.” If you ask him about the problems of this school of thought, the robot says “It’s too subjective.”

The robot was created by software engineer Jon Barber, using the most sophisticated autocomplete feature the world has ever seen: The GPT-3 speech production system from OpenAI, based on a gigantic neural network. GPT-3 can supplement texts based on minimal specifications or almost entirely write them itself. It can answer questions and even write software. Many developers have been allowed to play around with this new, amazingly powerful tool for just under a month. They have also created other amazing demonstrations.

The English Wikipedia is only a small snippet

But it also became clear where the problems of a seemingly intelligent machine lie — exactly where one had long suspected them to lie.

GPT-3’s extreme performance has a lot to do with the enormous size of the new tool: It consists of 175 billion parameters or 175 billion synapses in an artificial network. For comparison: a human brain has about 100 trillion synapses. One trillion is a thousand billion. So GPT-3 is far from simulating a brain, but it is a hundred times more extensive than its already quite impressive predecessor GPT-2.

The system was trained with a huge amount of text fished out of the Internet. This includes, for example, all of the six million or so entries in the English-language Wikipedia. However, this in itself a huge amount of text makes up only 0.6 percent of the total amount of material fed into the system. Exactly what GPT-3 has been fed is unknown.

Claude Shannon’s wife also had to guess

GPT-3 is a bit like the extraterrestrials that sometimes appear in movies, who sit in front of a running TV for two days and then speak and understand the world on that basis. This scenario alone always left you a bit perplexed — how exactly would the world view look like of someone who has learned everything he knows from “Celebrity Big Brother”, quiz shows and Chuck Norris movies?

There is also an important difference between the fictional aliens and the learning machine: GPT-3 doesn’t understand anything. Even today’s most powerful computers and applications manipulate pure “information”. And not in the common, colloquial sense, but the strict definition of Shannon and Weaver quoted at the beginning: “Information must not be confused with meaning”. Information is, therefore, a measure of statistical predictability, no more and no less.

GPT-3’s handling of text is indeed amazingly close to Shannon and Weaver’s original conception: It “guesses” how a given text snippet might proceed, based on statistical dependencies between words, sentences and text parts extracted from a gigantic amount of text. Claude Shannon himself, in the 1940s, had his wife guess how given sentences could go on to determine how many bits of information a given sentence contains. But there is a fundamental difference between Mrs. Shannon and GPT-3: What the words and sentences “mean”, the machine does not understand.

Creative, witty, profound, meta and beautiful

The essayist and researcher Gwern Branwen, who has had GPT-3 perform various tricks, nevertheless writes: “GPT-3’s examples are not only close to the human level: they are creative, witty, profound, meta and often beautiful.

The system can write (more or less successful) puns and Harry Potter detective stories in the style of Raymond Chandler, it can simulate an authentic crazy CNN interview with Kanye West, and dialogue between Alan Turing and Claude Shannon. Or write mocking poems about Elon Musk (one of the original financiers of OpenAI).

And because things other than human language are text, GPT-3 can also write other texts — guitar tablatures for example. Or software, which made John Carmack, the legendary “Doom” inventor, “shiver a bit”. The system is also capable of constructing a functional website or app interface based on a few simple instructions in normal English.

The machine must learn manners

The hand-picked examples of the system’s performance, initially presented in quick succession on Twitter or in developer blogs, of course, became too much for even the boss of OpenAI himself at some point. “The hype is way too big,” tweeted Sam Altman.

Even more problematic for Altman than the hype, however, were the quickly emerging problems that such an alien, who was not “educated” with television but with the chaotic Internet itself, inevitably had to cause: A GPT-3-based tweet generator, for example, produced extremely anti-Semitic or sexist text snippets when fed with certain terms.

This led to an interesting Twitter public debate between OpenAI boss Altman and Facebook AI boss Jerome Pesenti. During the discussion, the Facebook man spoke of dangerous “irresponsibility” and wrote this sentence, which his own company should take to heart: “The reference to ‘unintended consequences’ is what has led to the current mistrust in the tech industry. So far, the excuse “the machine did it” is mainly heard from companies like Facebook, Google, or Amazon.

People are often bad role models

GPT-3 thus directs a spotlight on the fundamental problem of learning machines, which is also evident in Facebook feeds optimized for wrath or extremist-conspiracy-theoretical YouTube recommendations: Humans are often miserable role models. Therefore, machines that learn from us are not to be trusted.

GPT-3 has not only learned from Wikipedia but probably also, as the US tech portal “The Verge” puts it, “from pseudo-scientific textbooks, conspiracy theories, racist pamphlets, and the manifestos of mass murderers”.

Tearing off the mask

In the meantime, OpenAI has built-in a “Toxicity Filter” to prevent the worst automated excesses. It’s as if the alien, who has learned his behavior from Chuck Norris movies, now urgently needs to be taught that you don’t knock others down as a greeting.

Or, to quote software developer Simon Sarris:

“We don’t tear the mask off the machine and expose a genius magician, we tear the mask off each other and show how low the bar is set.”

About the Creator

AddictiveWritings

I’m a young creative writer and artist from Germany who has a fable for anything strange or odd.^^

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.