Vincent Di Fate Interview

Science Fiction artist Vincent Di Fate is a painter of fantastic futures and a visionary of speculative fiction.

Science fiction artist and illustrator Vincent Di Fate is a master of unseen worlds. With each illustration depicting a voyage of the imagination, Di Fate skillfully crafts the worlds of tomorrow with the ideas of the future. From space adventures to futuristic creatures, artificial intelligence, and extraterrestrial invasions, Hugo Award-winner Vincent Di Fate has advanced the realms of science fiction, fantasy, and art through his many achievements.

A pioneer in his field, Di Fate was featured in the May 1981 issue of OMNI magazine, where his dark, moody, and powerful paintings depicted mechanical marvels and far frontiers of a future technocracy built on complicated machinery and human resourcefulness. OMNI magazine covered Di Fate’s Victorian belief in the mystical powers of the machine, saying that it is man who must bear the responsibility for his actions, not his science or his machines. With bold strokes and somber colors, Di Fate accents the powerful tools that will enable humankind to assert its citizenship in the universe. In an exclusive interview with OMNI, Vincent Di Fate reflects upon his breadth of science fiction art.

Vincent Di Fate, The 1984 Annual World's Best SF cover, 1984, Acrylic on Board

OMNI: What was the first science fiction film you ever watched?

Vincent Di Fate: I know beyond any doubt that the first science fiction movie I ever saw was Rocketship X-M. It was released in late May of 1950, just about a month before George Pal’s Destination Moon, and I was four at the time. I couldn’t tell you definitively if that was the moment I got hooked on science fiction, but the film left a lasting impression on me. About 10 or 12 years ago I finally acquired the original spaceship prop used for the film’s launch scene.

The launch footage from Rocketship X-M was reused the following year in Lost Continent, again in Monster from Green Hell (1957), and in scores of other films and TV shows. It has also appeared in documentaries about the genre and is among the most iconic images from the Golden Age of science fiction movies. Rocketship X-M was, technically, the first genre movie to be released at the dawn of the 50s science fiction boom.

I started reading science fiction soon after I learned to read, but I’m less certain of which was the first genre novel that I read. I recall a juvenile book entitled Young Visitors to Mars by Richard Elam, Jr. that I read in elementary school. I know I bought the paperback tie-in of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds around the time that the George Pal movie was released in the fall of 1953. I remember Heinlein’s Space Cadet, Star Beast, and Red Planet, and many other science fiction books for young readers, but I couldn’t tell you which one of these I actually read first.

How would you define the term science fiction?

To me, science fiction stories are tales in which science and/or technology are central to the plot and are typically the source of displacement and conflict about which the narrative revolves. Science Fiction is about change brought on by new aspects of science or new technologies that cause us to cope and adjust to different ways of thinking and living, or to be driven to extinction by our inability or unwillingness to do so. All great fiction, regardless of kind, is character driven, but the science in science fiction should be essential to the plot, and should provide us with food for thought as we look to the future.

A good example of this is the subject of artificial intelligence, which seems to be right around the corner. When self-aware machines are created, how will we be changed by this event? And at what point does a self-aware machine come under the protections of the law? Is destroying such a machine the equivalent of murder? Robots have always been used in the literature as metaphors for human slavery and alienation (the cyborg that is neither human nor machine, but who is rejected by both). Thoughtfully written books and quality movies are part of the cultural dialogue, and like many aspects of our culture, they hold a mirror to who we are. In the realm of science fiction literature, which is most often concerned with the future, there are opportunities to consider the long-range effects of our actions and to contemplate issues that may be fundamental to the survival of our species.

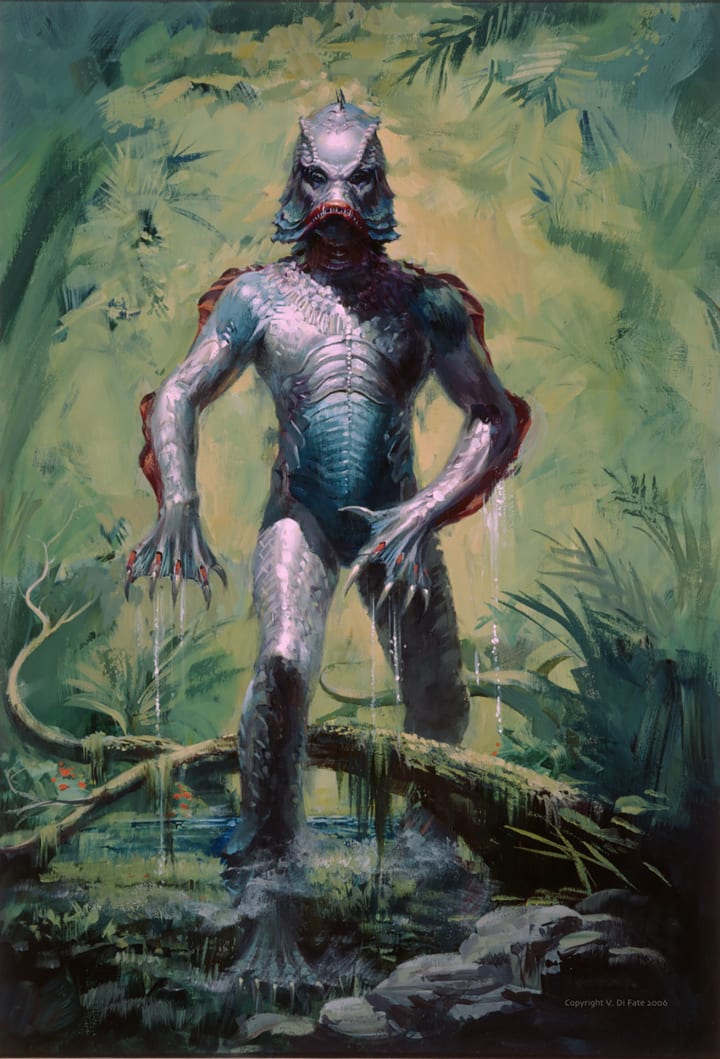

Vincent Di Fate, Creature Concept Painting, 2006, Acrylic on Board

Early on in your career, what influenced your style of painting? How has your art morphed from then to now?

In the beginning I never really set out to be an artist. I had inherent artistic skills that were apparent to everyone around me, but I was so self-critical that the joy of picture making deserted me early on. I still enjoyed the process of making art, but became dissatisfied with the limited results I was able to obtain. Perhaps some of this stemmed from early visits to art museums. I remember seeing the works of the great portrait painter John Singer Sargent and realizing that his artistic gifts were so vast that I could never rival them. I also recall seeing Yves Tanguy’s surrealist abstract masterpiece, The Multiplication of the Arcs at the Museum of Modern Art and feeling that the painting was alive with mystical power, as if I were looking through a window at a cityscape of the future. In that connect, from Sargent to Tanguy, I could see that art could be used to show others the unseeable—to show a vision of the world, not merely as it was, but as it might someday be.

Although I was, on some barely conscious level, able to make use of that idea in my work over the years, it has taken me a lifetime to put it together and to fully understand the ability of art to reveal, in sometimes brutal and unflattering terms, not only the human condition as it is, but to see beyond the present to what might lie ahead. I knew that art would play a role in some way in my future, but I had my ambitions set on wanting to be a filmmaker, and I especially wanted to explore this genre that I loved so dearly in film, because the science fiction movies that I grew up with were almost nothing like the stories in the books and magazines that I was reading. Film, after all, is primarily a visual medium.

There had been films with science fictional content since the very beginnings of commercial cinema (Méliès's 1902 masterpiece, A Trip to the Moon, for example) but prior to the 1950s, the science in many of these stories was merely a device to provide a more credible rationale for fantastic events to an increasingly sophisticated audience that could no longer suspend its disbelief in the supernatural. In the 50s, during which nearly 400 films of the fantastic were produced and released to movie theaters, the overwhelming majority of those films were about our fears of the Cold War and the consequences of the Atomic Age. Aliens behaved like communists, assuming human form and taking over our minds and souls; Atomic radiation was releasing prehistoric monsters from their slumber of ages, or mutating common insects into creatures of gargantuan size. It really wasn’t until Star Trek appeared on TV in 1966 that science fiction in moving image media began to resemble science fiction on the printed page.

On a more positive note, and to return to your question about artistic influences, the technologies that emerged from the Second World War had also brought us the promise of space, and artists like Chesley Bonestell created vividly convincing tableaus of majestic worlds beyond our own. So, Bonestell was almost certainly the very first illustrator that I began to pay careful attention to—through his work in the Collier’s magazine space series and in Life’s long-running "The World We Live In" series. I’m fairly certain that, other than Norman Rockwell, the illustrator whose name every American knew in the era of the great magazines, Bonestell’s name and work took on special meaning for me. His reverential visions of far-flung alien worlds bathed in the cool, elegant light of space, were as magical to me as Tanguy’s The Multiplication of the Arcs.

Also in the 1950s, paperback books became a real factor in my obsessions with the genre. Cover art by Robert Emil Schulz and Stanley Meltzoff filled me with wonder and fired my imagination. Before I could even read and understand the stories within those covers, I would spend hours imagining the fantastic narratives that awaited me. Meltzoff’s cover painting for Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters, though it has little to do with the novel, is a science fiction masterpiece by my standards. Meltzoff’s chiaroscuro treatment of the alien invasion theme is pure artistic alchemy—a veritable Rembrandt of futurism.

And somewhere in the process of admiring the best of my profession, I found a voice and a visual vocabulary of my own. I’m still a work in progress with much left to do.

Vincent Di Fate, A View From Iapetus, 2016, Acrylic on Board

What is your process of illustration? How do you envision the story at hand?

One of the key talents that distinguishes illustrators from both other kinds of artists, and from non-artists, is that when an illustrator reads a story, the images appear instantly in his mind. As a commissioned illustrator, I’m always mindful of the accompanying narrative—and always looking for the visual hook that’s going to make a potential reader pause to question, "What’s going on there?" and draw them in. Some authors write with simple, but powerful word-pictures—Arthur C. Clarke comes immediately to mind.

One personal example is a cover illustration that I did for George R. R. Martin’s first novel, The Dying of the Light. It was serialized in Analog and the magazine ran the novel in installments as After the Festival, which I understand was George’s intended title before its appearance in book form. As with all of George’s incredible writings, the novel is character driven and deals mostly with an exotic and complex cultural system and the subterfuge between competing factions. In this case it all takes place in 14 cities scattered across a rogue world as it moves away from the light of a red giant star into certain death in the cold reaches of limitless space.

Analog was going through a "gadget of the month" phase at that point and I’d been asked specifically to find some technology that would make a decent cover. About halfway through the novel the author mentions that the protagonist and several of his colleagues get into a bat-winged, anti-gravity vehicle and fly to the other side of the planet. There was no more description than that, so I was really flying by the seat of my pants.

Well, the novel was a huge success and it ended up as a Hugo finalist that year. Soon after, George and I were invited to be guests at a science fiction convention. During a panel that we were both on, George commented that I had exactly captured the craft as he’d described it, yet there had been no more description in the story beyond what I’ve just mentioned. So, the particular selection of words that George had chosen to describe the vehicle had triggered that particular image in my mind. I was, of course, deeply pleased and flattered at the time, but I am certain that if I were to illustrate that vehicle today, it would look quite different from the way in which I first envisioned it.

Vincent Di Fate, Revolt in 2100 cover, 1979, Acrylic on Board

If you could design the concept art for any up-and-coming science fiction film, which would you choose?

My, that list would be endless. There is a virtually untapped world of literature that would make for some great science fiction cinema and it would be virtually impossible for me to select just one. I tend to be attracted to epic projects that would have me designing an entire universe of characters, props and environments.

I will say, however, that even though it is marginally science fiction, one of the films that I’d love to work on is the intended remake of the 1954 movie, Creature from the Black Lagoon. There have been numerous attempts to do a Creature remake since 1967, and about a decade ago producer Gary Ross purchased the option. He’s held that option the longest of any of the dozen or so others who’ve attempted to do this. In 2007, Greg Nicotero asked me to do a Creature re-design that he was interested in pitching to Ross and Universal, but Greg soon became involved in the development of the TV series The Walking Dead, and that was the end of it. Of all of the creatures to appear in monster movies in the 1950s, the Gill Man (Creature) is perhaps the most ambitious, and almost certainly the most convincing in appearance.

Re-designing him in a way that pays homage to the original, yet updates the character to the current state of cinematic special effects, poses some unique challenges. I did come up with several promising designs and continue to develop ideas for his updated appearance. Also, the original movie had a great looking title character in the Gill Man, but it had little more than a functional script. Given the original film trilogy, and the Gill Man’s character arc in them, creating a richer, more epic vehicle to tell his story would be quite a creative undertaking.

Vincent Di Fate, Star Fire cover, 1987, Acrylic on Board.

You provided beautiful images for OMNI magazine in the 70s and 80s. What was it like contributing art to the magazine?

OMNI was an incredible showcase—a large format magazine with slick pages, access to full-color throughout, and the incredible, eclectic tastes and design sensibilities of art director Frank Devino. It was a similar situation to working with Len Leone at Bantam Books at the time—you just wanted to do your best for these gentlemen, knowing that they would treat your art with respect, sophistication, and impeccable taste. OMNI was a chance for the genre to break out of the literary ghetto of the pulp/digest magazines to be found by a broader, more visually astute audience.

The other magazines were offering up great science fiction stories at the time, too (this was the New Wave era, after all), but if you were not a die hard science fiction fan who could see the genre beyond the economic limitations of those publications, you might be inclined to dismiss it based purely on its appearance alone. A great cover painting on a digest will pale in comparison to an inferior cover painting on a full-sized magazine. If you can’t see it, you can’t respond to it. Even in newsstand placement, OMNI offered the genre a significant step up in visibility.

How would you define your art?

Still evolving. I am the worst judge of what I do. I hate almost all that I produce and am intent on doing better. This comes not from a lack of effort or of dedication, but from wanting to be better than I am. I’ll leave it to others to define the flaws and merits of my work.

If you had to choose a favorite painting from your vast career, which would it be and why?

I truly have no favorites, though I like some more than others. My favorite is always the mind’s-eye vision I have when I first finish reading a story, but that I somehow can never fully realize on paper. Over considerable time I do come to view these more objectively, but it takes me decades to do so.

Vincent Di Fate, Lift Off From The Moon, 2010, Acrylic on Board

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave in the world of science fiction art?

I think "legacy" is perhaps too great an ambition to associate with my work. I hope not be to forgotten too quickly after I’m gone. I hope that something in my work speaks across the barriers of time and death to someone young and full of hopes and dreams as I was when I first gazed upon The Multiplication of the Arcs, or on Meltzoff’s The Puppet Masters. Who could want more after one’s demise, than to live on through one’s art?

In your book 'Infinite Worlds,' with a foreword by Ray Bradbury, you explore the evolution of the genre of science fiction art. How has it morphed into what it is today?

The science fiction genre has become decidedly mainstream these days, and that’s a good thing. There are many talented artists working in the field now, not only in the print media, but as character and production designers and illustrators working with near anonymity in moving-image media. If I were to write a sequel to Infinite Worlds it would embrace this broader spectrum of work that extends far beyond the printed page. Knowing the realities of commercial book publishing, and the reluctance to take risks by producing highly expensive 1,000 page picture books, there would probably have to be more than one follow up volume.

Vincent Di Fate, Ares and the End of All, 2015, Digital and Acrylic on Board

On a more speculative note, do you believe there is life outside of Earth?

Of course. In my view, UFOs are largely a cultural phenomenon and are of interest purely from that standpoint, so I don’t think they’re visiting us with any regularity. I do believe, however, that the universe is fairly widely populated. More importantly, I believe that our perceptions of reality, limited by our senses and by our consensus views of the external world, are grossly confining and imprecise. Having been recently and profoundly touched by death, I no longer believe in death in the tradition sense and, being mindful of the lessons that the genre has to offer, I deeply question the "wisdom" that we refer to as conventional. Perhaps it’s just wishful thinking on my part, but I’m convinced that there’s more going on here than meets the eye.

If any world depicted in your art could become a reality, which world would you choose?

I really haven’t depicted that reality on paper yet. Like any self-respecting science fiction fan, I dream about the world to come and I can imagine scenarios of a future of abundance, of peace, and of eternal bliss. Conflict is the nature of the human narrative. Without it, there are no stories, thus the world that I long for most to image would not make for great visual storytelling. But it is the world I wish most that could be.

Vincent Di Fate's Infinite Worlds : The Fantastic Visions of Science Fiction Art contains a dazzling array of almost 700 images, 600 of them in vibrant color. The images encompass some of science fiction's finest examples of futuristic art.

About the Creator

Natasha Sydor

brand strategy @ prime video

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.