Rod Serling's 'The Twilight Zone'

Rod Serling’s ‘The Twilight Zone’ started a phenomenon of science fiction TV anthologies, surprising fans weekly.

The television screen fades to black. From out of nowhere, a faint starfield appears: an endless swath of space that slowly begins to twist and turn before the camera's eye. A message seems to be coming into view.

“There is a sixth dimension beyond that which is known to man,” intones an omniscient voice. “It is a dimension as vast as space and as timeless as infinity. It is the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition, between the pit of man’s fears and the sunlight of his knowledge. It is the dimension of the imagination. It is an area that we call... The Twilight Zone.”

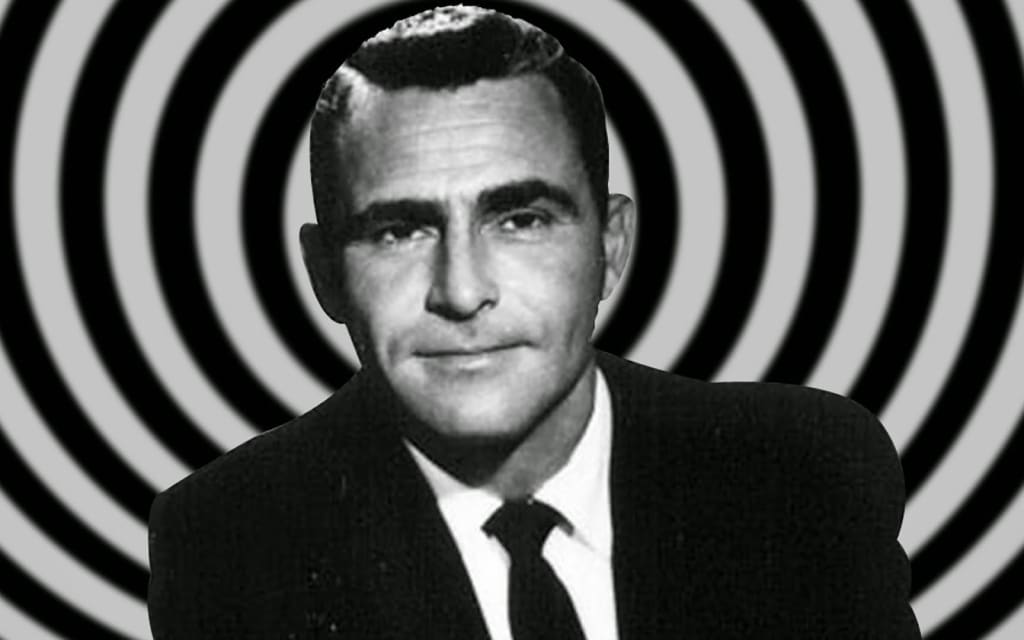

From the center of the cosmos, the jagged logo of The Twilight Zone bursts forth, and then disappears, across the screen. A lone figure is seen standing stoically before the television equivalent of a void. Hands clasped before him, the figure speaks in a clipped, deliberate fashion. He was the narrator, the guide, the creator of The Twilight Zone... Rod Serling.

It was Serling who dictated the goings-on within the strange video realm. It was Serling who would completely revolutionize television week after week with his unique anthology series. He would defy the rules of the broadcasting game by appealing to his viewers’ imaginations and not their pocketbooks. He would fight the system hour after hour, day after day, year after year in order to insure his show's integrity.

In the end, he became an idol to millions and a stereotype in his own eyes.

Image via The Portland Mercury

"... It's Not a Spook Show."

When the Twilight Zone premiered in that fall of 1959, no one, with the exception of creator Rod Serling, realized that this harmless little “ghost” show would shake the television kingdom by its rafters, becoming one of the most talked about shows in the history of broadcasting—inspiring a horde of similar series from Outer Limits in the 60s to Fantasy Island in the 70s. Critics, who had been prepared to dismiss the show as a juvenile effort filled with rehashed Karloff-Lugosi antics, found themselves applauding Serling’s brilliant excursions into fantasy. A startled CBS network, totally unprepared for the quality of the series, delightfully began referring to this unexpected windfall as a “prestige” show.

For Serling, however, The Twilight Zone was just another scrimmage in his life-long battle to bring intelligence to the expanding medium of television. Serling was not afraid to defend his fledgling series from TV’s commercial wolf-packs and, indeed, would do so for years to come. Never a man to walk away from an argument, Serling, from The Twilight Zone's very inception, proved a fearless opponent against the onslaught of bureaucratic executives who sought to undermine his efforts.

“It’s not a monster rally or a spook show,” the author stated a month after the series had premiered. “There will be nothing formula’d in it, nothing telegraphed, nothing so nostalgically familiar than an audience can join the actors in duets. The Twilight Zone is what it implies: that shadowy area of the almost-but-not-quite; the unbelievable told in terms that can be believed.”

The Twilight Zone was, in effect, Rod Serling’s totally ingenious way of presenting thought-provoking entertainment to a TV audience weaned on The Honeymooners and The Cisco Kid. In essence, he was sneaking high voltage, speculative fantasy in on an unsuspecting public. From the outset, he knew this was a risky move. If he succeeded, he would be declared a hero. If he failed, he would suffer an almost suicidal career setback. It was a risk and a dangerous one, but Rod Serling was used to taking risks. In fact, he relished the chance to do so. For the next five years, he would proudly put his neck on the network line on behalf of his brainchild—time and time again. As a result, he would win three Emmys for one show and be kicked off the air unceremoniously at the end of its run.

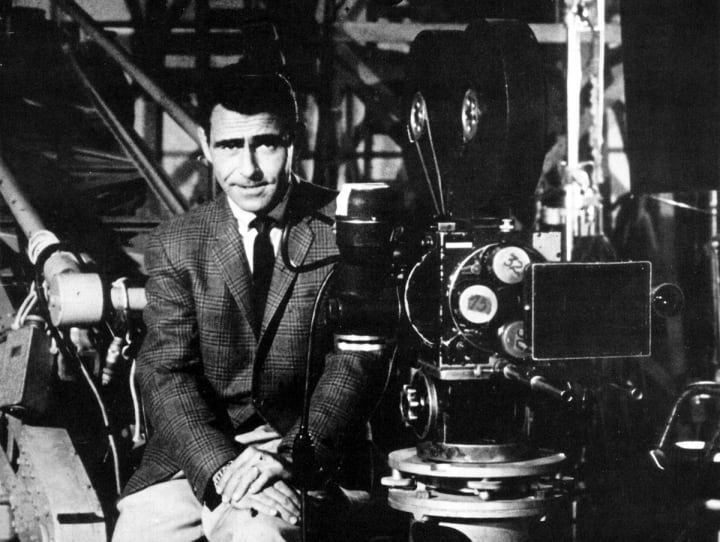

Image via Los Angeles Times

The Rise of the "Angry Young Man"

The Twilight Zone was Rod Serling. Its climate, its population, and its geography were all a reflection of Serling’s kinetic imagination. To trace the show's developments, its quirks, is to trace the development of a two-fisted writer who fought his way into the hearts and minds of the American public—while not yet out of his twenties. “Writing is a demanding profession and a selfish one.” Serling once reflected. “And because it is selfish and demanding, because it is compulsive and exacting, I didn’t embrace it. I succumbed to it.”

Before turning to writing as a career, young Rod Serling had shown a marked preoccupation for fighting the odds, no matter how great, and in any and all situations. His lust for life led him constantly into Don Quixote-like situations jousting him with some of everyday living's most Olympian windmills. It was a joyful compulsion.

The son of a Binghamton, New York butcher, the diminutive, 5’ 5” Serling pursued life with a passion, diving into the world of sports while still in his late teens. Eventually, he became a Golden Gloves boxer, winning all his bouts but the last; an unfortunate encounter which left his nose in a slightly altered state. During World War II, he was an Army paratrooper and, because of his adventurous nature, received a Purple Heart.

The horrors of war, however, sparked something inside of Serling that he found hard to exorcise by conventional means, a nagging spectre in the back of his mind that couldn’t be assuaged via gymnasium workouts or long walks. While attending Antioch College on the G.I. bill after the war, Rob began writing, incorporating his fascination for the human spirit into his pieces. He rid himself of World War II’s mental leftovers and began to experiment with style. He gradually became absorbed in his writing, attempting to break into the growing field of TV drama. He wrote some 40 scripts without a single sale.

After college, he attempted to write copy for a local Cincinnati TV and radio station. That experience proved frustrating. His introspective characters constantly came under attack by high minded executives who wanted their “people to get their teeth into the soil!” Serling recalled the period years later, quipping, “What these guys wanted wasn't a writer, but a plow!”

Turning to his wife Carol for moral support, Serling hesitantly embarked on a career as a freelance writer. Success was not long in coming. In 1955, his teleplay Patterns, a tale of corporate intrigue, won Serling his first Emmy Award. In 1956 Requiem For A Heavyweight garnered a second, as well as the first Peabody Award ever presented to a writer. In 1957, Serling copped a third Emmy for his play, The Comedian. To this day, Rod Serling has won more Emmys than any other writer in television history.

By the late 50s, Serling had garnered the reputation of being an “angry young man.” Television, however, was growing quickly, adapting slicker, sleeker methods that forced many such angry writers out of the business. The 90-minute dramas concerning burning issues were being axed, replaced by half-hour situation comedies and benign westerns. Entertainment was the name of this game. Sponsors demanded “safe” programs to showcase their products. The networks wanted sponsors. Burning issues were thus allowed to cool.

For Serling, this gradual shift in television programming was anything but a surprise. Years before, he had found the network censors to be spineless. “Once,” he stated, “I couldn’t mention Hitler's gas ovens because a gas company sponsored the show.” And so, in 1957, Serling began to plan his leap from “serious” television drama to “sheer fantasy.” “I simply got tired of battling,” he remarked, explaining his much-publicized switch. “You always have to compromise your script lest somebody—a sponsor, a pressure group, a network censor—gets upset. The result is that you begin to settle for second best. You skirt the issues.”

From that point onward, Serling publicly stated that he would purposely skirt the issues. His days as an Angry Young Man were over, he declared. He was, after all, over the age of thirty and getting to be quite a mellow guy. He wrote an hour-long pilot called The Time Element for CBS as a prelude to The Twilight Zone.

And how did the uncontroversial, mellowed-out Serling tackle the realm of fantasy? Suffice to say that this drama’s hero was a fellow who foresaw the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor in a dream and could convince no one of its validity. CBS took one look at the pilot and backed away from Serling's proposed series. When the hour-long installment was finally aired as an episode of Desilu Playhouse that year, it attracted the largest amount of mail of any episode shown during 1957.

CBS, smelling success, allowed Serling to film another pilot for Where is Everybody?, a half-hour drama. Serling again played with the boundaries established by play-it-safe corporate minds, coming up with one of the few episodes of The Twilight Zone to actually have a logical ending. An astronaut, surrounded by a seemingly deserted world, turns out to be the guinea pig in a psychological isolation test which produces the delusion that he’s the last man on Earth.

Safe stuff, right? General Foods thought so and, in February of 1959, decided to sponsor the show for that fall. Serling was more than willing to publicly cooperate with the powers-that-be. “I’m not writing anything controversial in the new series.” The then-thirty-four-year-old genius added slyly, “Now that we’re petulant aging men, it no longer behooves us to bite the hand that feeds us.”

By the winter of 1959, it was clear that The Twilight Zone was, in its own way, the most controversial show Serling had ever come up with. The viewers realized it almost at once. It took the network and the sponsors a little longer to figure out what was really going on. Then, all hell broke loose.

Image via Time Out

"... They Want to Cancel!"

During the first few months of its coast-to-coast lifespan, The Twilight Zone struggled for survival. Being the very first network science-fiction/fantasy anthology of any merit, it took a while for the show to catch on with the public. Initial ratings were horrendously low, although that situation was destined gradually to change. The sponsors became nervous. The network began to grumble. Even in those lean days, Serling somehow found positive arguments to use on the show's behalf. Concerning its initial ratings, he exploded. “Fifteen million viewers (saw the show)—more than saw Oklahoma! during the entire run of the show on Broadway, and they want to cancel us!!”

The show refused to die. Word of mouth spread and the critics openly praised it to the heavens. The ratings began to inch upward and Serling successfully unveiled shows concerning the adventures of Mr. Death, a time traveling businessman, a faded Hollywood goddess who literally lives in her old movies, a murdering astronaut, a hapless guardian angel, a marooned convict in love with a female robot and a child who could make wishes come true. Each episode delved deep into human emotion—the fears, the joys, the triumphs, and the downfalls of everyday living. Writer Serling clearly relished the nuts and bolts of the world around him, and his interest was infectious.

As the show became more and more notorious, Serling slowly began to shift his public stance concerning The Twilight Zone. No longer was the show an exercise in safety. “We want to prove that television, even in its half-hour form, can be both commercial and worthwhile,” he pointed out. “We want to tell stories that are different. At the same time, perhaps only as a side effect, a point can be made that the fresh and the untried can carry more infinite appeal than a palpable imitation of the already proved.”

Rod Serling was once again at odds with “the system.” Hollywood agents, who saw the show as nothing more than a monster gallery, submitted gigantic actors with necks long enough to hang electrodes from. Authors submitted stories concerning the ultimate monster situation. Serling, however, remained adamant about the show’s direction, stating that The Twilight Zone “probes into the dimension of the imagination but with a concern for taste and for an adult audience too long considered to have IQs in the negative figures.”

The narrator-writer had creative control of the series and relied only on the finest of material and authors in putting together his weekly shows. Besides Serling himself, the early The Twilight Zone relied on such brilliant minds as Richard (The Incredible Shrinking Man) Matheson and Charles (The Seven Faces Of Dr. Lao) Beaumont for story ideas. According to Serling, this was all part of a master plan. “Each story is complete in itself,” he explained. “This anthology series is not an assembly line operation. Each show is a carefully conceived and wrought piece of drama, cast with competent people, directed by creative, quality-conscious guys and shot with an eye toward mood and reality.”

The Twilight Zone's scope of vision expanded greatly during the second season, including robots, the devil, justice-seeking machines, paranoid citizens, nasty aliens, and magic Santa Clauses within its ranks. For some odd reason, the show's resident menagerie of characters startled some of its sponsors. The great migration of 1960 began.

General Foods and Kimberly-Clark left. Colgate-Palmolive entered the Zone, then jumped ship. Chesterfield cigarettes did likewise. From that point onward, sponsors entered and exited the show's domain on a revolving door policy, keeping the network nervous and Serling in a state of constant anxiety concerning the continuing quality of his show.

Before long, Serling was writing and rewriting like a man possessed. Smoking up to four packs of cigarettes a day, the author would often work in 18-hour shifts, worrying both about his ever-struggling show and the prospect of a smothering writer’s block. In the back of his mind, Serling had the idea that one day his talent would simply stop. He fought against this imaginary deadline furiously, churning out a constant flow of ideas. “In my writing, I work with a secretary and a recorder,” he once informed reporters. “I dictate everything. It’s a freewheeling thing. I act out all the parts. I do three or four drafts but by the time I get through with the second, things are pretty well set.”

On numerous occasions, Serling found himself writing during the hours he should have been sleeping. Naturally, as the show's popularity increased, this practice almost became routine. With over 30 shows demanded per season, the feisty writer was faced with the chore of putting together a finished half-hour segment in a three-day shooting schedule. Although the pressure to keep The Twilight Zone going was great, Serling relaxed from time to time, enjoying the prestige connected with the series. “We’re part of the language now,” he once beamed proudly. “Archie Moore, when he last got knocked out, said he felt like he was in the 'twilight zone.' Dean Rusk spoke of the 'twilight zone' in international diplomacy and there is a 'twilight zone' defense in basketball.”

As host of the show, Serling was becoming as famous a TV star as he was a writer. “There I am,” he laughed. “5' 5" of solid gristle. I really don’t like to do hosting. I do it by default. I have to. If I had my druthers, I wouldn’t do it. I just tense up terribly before going before the cameras. It’s an ordeal. If I had to go on live, of course, I’d never do it. It’s like boxing. I’m the only fighter in history who had to be carried both into and out of the ring.”

Serling had the good humor to resist the egomania attached to cult fame. Whenever he did find his head swelling to star status, he could rely on his family to gently deflate his growing hat size. About to receive a deluge of The Twilight Zone-inspired awards, including the keys to a few cities, Serling was approached by his wife who reacted by smiling sweetly and saying, “If you don’t laugh, I’m going to divorce you.” Serling's visions of grandeur promptly crumbled amid a barrage of giggles. On another occasion, when pictured in Time magazine, Serling proudly approached his then-infant daughters, Jody and Nan, with the issue in hand, beaming, “Do you know why I'm in there?" Jody looked at the magazine closely, and then looked at her father. “Who’d you shoot?” she asked solemnly. There simply was no room for egos in the household, a fact which pleased Serling immensely.

Despite his good humor, Serling found that, by the third season, the fight to keep The Twilight Zone artistically valid was getting on his nerves. “I’m tired of it,” he sighed to one interviewer, “as most people are when they do a series for three years. I was tired after the fourth show. It’s been a good series. It’s not been consistently good, but I don’t know any one series that is consistently good when you shoot each episode in three days. We’ve been trying gradually to get away from the necessity of a gimmick, but the show has the stamp of the gimmick and it’s hooked for now. It’s tough to come up with them week after week.”

By the end of the third season, Serling had written 62 out of the 92 shows televised. Although The Twilight Zone was widely acknowledged as a quality series, Serling was obsessed with the idea that a perfect series had eluded his grasp. “I guess that a third of the shows have been pretty damn good,” he reflected. “Another third would have been passable. Another third are dogs— which I think is a little better batting average than the average show. But to be honest, it’s not as good as we thought or expected it might be.”

Serling, apparently, was not the only party involved with the show who demanded perfection from The Twilight Zone. At the end of its third season, The Twilight Zone was cancelled… almost.

Image via Third Monk

"Something Totally Different"

CBS let the axe fall on the critically acclaimed The Twilight Zone during the latter half of its third season. Stunned, Serling discovered that his show had been replaced by a terminal comedy about a family-swapping pair of teenaged girls, one British and one American, entitled Fair Exchange. “Anybody would rather quit than get the boot,” he reflected. “On the other hand, I am grateful. We had some great moments of vast excitement and, on occasion, achieved some real status. But now it’s time to move on.”

Serling left to teach at Antioch College and to write the screenplay for Seven Days in May. During his absence, however, Fair Exchange flopped and CBS decided to revamp their favorite prestige show… TheTwilight Zone. In its own small way it was a solidly popular show, the network reasoned. Somehow they had to come up with a way to increase its ratings. During a series of brainstorming sessions, one corporate mind came up with the ideal solution. If The Twilight Zone attracted, let’s say, 15 million viewers in a half hour format, wouldn’t it attract 30 million in an hour-long slot?

And so, The Twilight Zone was trotted out as an hour-long series during its fourth season. “In the half-hour form we depended heavily on the old O. Henry twist,” Serling said with forced optimism at the beginning of the season. “So the only question is: Can we retain the Twilight flavor in an hour? We may have to come up with something totally different.”

The “something different” the elongated show came up with turned out to be boredom. After 13 publicly shunned episodes, the 60-minute Twilight Zone was cancelled. During its fifth season, it returned as a half-hour brainteaser, but by that time no one at CBS really cared about the series. It was subsequently cancelled... “for reasons totally unknown to me,” Serling groused. “The other time we were tossed off the air with the knowledge that we might come back in an hour form. But this time we have no assurances that we’ll ever come back, even as a five-minute commercial. In a strange way, I don’t blame them (the network executives),” Serling confessed. “To this extent, we’ve been on the air five years and I think the show took on a kind of aged look.”

The Twilight Zone was almost salvaged when ABC approached Serling about revamping the show for a sixth season. Serling refused, stating that “I think ABC wanted a trip to the graveyard every week.”

Serling parted ways with The Twilight Zone, allowing the show to lapse into syndicated reruns, and went off to other projects. Haunted by the possibility of becoming known only as the has-been “ghost show” creator, he plunged headfirst into a mountain of projects. He wrote the screenplays for such films as Planet Of The Apes and The Man, worked on a few Broadway plays and did numerous television commercials just to keep himself busy when not thinking. For Rod Serling, the lover of life, the master of risk-taking, free time was a trap to be avoided.

By 1970 he was back on the air with a mini-series entitled Night Gallery—a gothic, hour-long anthology that echoed The Twilight Zone in some respects but lacked its intellectual clout. Critics disdained the show, taking Serling to task for foisting such a banal show on his fans. As it turned out, Serling was one of the show’s harshest critics himself.

He had backed himself into a creative corner in an effort to launch the show, allowing himself to lose creative control of Gallery to both NBC and producer Jack Laird. In various formats, the show limped along for three years before dying a much-deserved death. Serling was contractually bound to host the weekly installments, a fact which pleased him little. “The way the studio wants to show it,” he complained, “a character won’t be able to walk by a graveyard; he’ll have to be chased. They’re trying to turn it into Mannix with a shroud!”

Yet, Serling continued to fight doggedly against the odds—all odds. On his fortieth birthday he made his first parachute jump since World War II. “I did it for one reason,” he revealed. “I had to prove I wasn’t old.” During his tenure with Night Gallery, when many of his scripts were being rejected because of their unabashed quality, Rod still managed to sneak in a few zinger stories before the show's collapse. Two were nominated for Emmys.

Image via The Daily Beast

Into the Twilight Zone

During the early 1970s, the former wunderkind of television’s Golden Age tormented himself with thoughts of self doubt concerning his craft. A TV film, The Doomsday Flight, presented the idea of an extortionist planting a bomb on an airplane. Shortly after the Serling show was televised, the event occurred in real life. Serling apologized publicly to the world for writing the script. He later apologized for making the original apology, adding, “A writer can’t be responsible for the pathology of idiots.”

Still, he was publicly disgusted about his long association with television. “To write meaningful, probing things for television nowadays is an exercise in futility,” he remarked in 1972. That same year he was interviewed by a journalist in an office with framed reviews of his plays from the 50s. “Sometimes I come in here just to look,” he stated. “I haven’t had reviews like that in years. Now I know why people keep scrapbooks—just to prove to themselves it really happened.”

Rod Serling died on June 28, 1975 in Rochester, New York, of complications following open-heart surgery two days earlier. He was fifty years old, a veteran of a twenty-year love-hate relationship with television.

Although publicly Serling muttered about his constant video battles, there were softer, prouder moments when he reflected on some of his accomplishments with satisfaction. All his life, through his writing, he conducted a one-sided love affair with humanity. He took great delight in pinpointing the essence of an individual, the parts that make someone tick, and presenting his findings coast-to-coast over the small video screen. “I’ve my moments of depression,” he admitted a year or so before his death, “but I guess you’d say I'm a pretty contented guy.”

Thirty years after his death and over 50 years after his beloved The Twilight Zone's cancellation, Serling can still be seen sauntering onto the TV screens of millions of viewers via reruns, bringing his insight and his marvels to audiences worldwide. As it turns out, Serling’s one-sided love affair with humanity was not unrequited after all. With The Twilight Zone entering its umpteenth season of syndicated reruns, its audience mushrooms at a phenomenal rate. New generations of fantasy lovers, of intellectuals, humanitarians, nostalgic adults, and awestruck children cling to the show lovingly, faithfully; pushing its overall national rating a quantum leap beyond the Zone’s original 1959-1964 figures.

Back during the show's final, troubled two years, Serling took the time to prophesize to one writer, “Fame is short-lived. One year after this show goes off the air, they’ll never remember who I am. And I don’t care a bit. Anonymity is fine with me. My place is as a writer.”

The five-time Emmy award-winning writer-producer-narrator had been right about many things during his lifetime. Fortunately, for millions of The Twilight Zone fans around the globe, in this case he was as wrong as a man can be.

Rod Serling will always be remembered. His thoughts, his insights will be cherished as long as The Twilight Zone exists. And, as everyone knows, The Twilight Zone is “as vast as space and as timeless as infinity.”

Explore Rod Serling's seminal anthology series, The Twilight Zone, about regular people who suddenly find themselves in extraordinary situations.

About the Creator

Futurism Staff

A team of space cadets making the most out of their time trapped on Earth. Help.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.